Lest We Forget

Brian Ashton outlines a catalogue of cruel and harsh treatment meted out on the soldiers of the British military during the First World War set against a background of the use of force against working class struggles in pre-war Britain. Maltreatment of workers and soldiers continued through the entire war, with the shell shocked soldiers subject to sadistic treatments born of propaganda encouraging mistrust of the working class. In what is still a little-told story, of those traumatised by the violence of the war, Ashton brings together the accounts and records that document this period.

We are in the midst of the remembrance fest that is supposed to honour the memory of those who fought in the First World War. But what is being remembered and for whose benefit? Let’s deal with the second part of the question first. It benefit’s the politicians who are currently waging war on us; they can parade their patriotism before the cameras, with their faces suitably solemn and the poppies bright against the grey of their suits. It also benefit’s the companies that have been busy producing commemorative tat. As to the first part of the question: What are we supposed to remember? This ex-squaddie thinks we should remember the things they would like us to forget, lest we forget them. But before looking at the issues that caused anger and concern during the war and after, those being executions, shell shock and mutinies, let’s take a look at the period immediately before the war. 1910 to 1914 saw a sharp rise in working class militancy and a concomitant rise in anti working class propaganda. The verbal assault on an increasingly politicised class was backed up by the use of force, including military force.

The prewar period saw an increase in trade union membership from 2.1 million to 4.1 million and an average of ten million working days per year lost through strikes, including major struggles breaking out in the mining and transport sectors.1 These strikes were unlike the struggles of the late nineteenth century, with Eric Hobsbawm contrasting them as ‘the evangelistic organising campaigns of the dock strike period’, and the ‘mass rebellions’ of the later explosions. As Bob Holton points out in his book British Syndicalism 1900-1914, the most striking difference was ‘the high degree of aggressive, sometimes violent and often unofficial industrial militancy during the latter explosion.’ The army was used against striking workers in order to intimidate those involved and to deter others from taking similar action. During the Liverpool transport strike of 1911 the government sent a gunboat to the Mersey, and some 3,000 troops were dispatched to the city, while the city’s police force was reinforced by hundreds of officers from other constabularies. One historian described the Liverpool strike as near to revolution.

Police make arrests in Liverpool during the transport general strike in 1911

There were violent confrontations between workers and the armed state during the strikes of the period. Two workers were shot dead in the Liverpool conflict and the Welsh coalfield strike of 1910 saw a worker killed in Tonypandy. During the 1911 national railway strike workers resorted to sabotage and engaged in violent conflict with the forces of state. Strikers attacking a railway station in Chesterfield set the building alight, and they were only driven off after repeated bayonet charges by the army. One of the most notable aspects of the period was the active solidarity shown by workers in other industries. During conflict in Llanelly, where railway installations were seized to prevent the movement of rolling stock, two workers were shot dead and others were bayoneted. None of those killed or wounded were railwaymen. And it was not only workers who were in struggle during the period, a total of 62 strikes by schoolchildren took place in towns and cities across the country in 1911. And then the war; it is safe to say that many of those who had confronted and fought the forces of the state in the preceding period volunteered to fight in that war. In Liverpool volunteers signed up at a recruiting station set up on St George’s Plateau, which, in 1911, had been the scene of a violent attack by the police against striking transport workers and their families.

Police with Armored Vehicle at Liverpool Transport Strike 1911

When the working class moves from a class in itself to a class for itself then the capitalist propaganda machine goes into overdrive. The weekly magazines and journals read by the middle classes contained umpteen articles on degeneration, only psychic phenomena took up more printing ink. It was claimed that the levels of alcoholism, lunacy and mental deficiency were on the rise, confirming for some that the country’s racial stock was declining. The middle class birth rate was falling, but that of the very poor, what they called the residuum, remained high. Residuum is a chemical term for a substance left over after combustion or evaporation. Perhaps if the working class had had the same access to medical provisions things would have been different. The Eugenics Education Society declared: ‘The brain of this country is not keeping pace with the growth of weak-minded imbecility and vice’. And Home Secretary Churchill, in 1912, stated that ‘the multiplication of the Feeble-minded was a terrible danger to the race.’

During the Battle of the Somme, British soldiers from the Cheshire Regiment, July 1916

The attitudes of the ruling class were indicative of the opinions prevalent within the commissioned ranks of the military. Attitudes and opinions, inculcated by the public school system, were carried over into military life. And what did the public school system do? The Clarendon Commission of 1864 stated that it was ‘an instrument for the training of character.’ It went on,

‘The English people were indebted to these schools for the qualities on which they pique themselves most – for their capacity to govern others and control themselves, their aptitude for combining freedom with order, their public spirit, their vigour and manliness of character, their strong but not slavish respect for public opinion, and their love of healthy sports and exercise.’2

The officer class feared that:

‘The traditional military qualities of the army and the nation were being eroded and undermined by too much individualism and too little discipline; the rise of unpatriotic working-class politics; the instability of the town-bred masses…and the declining military virility of the nation.’3

Some, like Colonel Baden-Powell, thought that conscription was the answer, that it would ‘discipline the nation by imposing compulsory military service on its youth.’ Others thought that ‘the military instincts of the race were best expressed by the esprit de corps and primordial enthusiasm of the volunteer spirit.’4

There was agreement, though, that morale was of great importance in modern warfare; but how to keep it on tap raised some discussion. Military thinkers disagreed as whether the soldiers will to fight was best mobilised by sterner discipline or by the inculcation of such vague abstractions as ‘racial cohesion’ or ‘national fighting instinct’ and ‘a sense of duty, honour and self sacrifice’.5 I would argue that both methods were used; the vague abstractions to get men into the army and the harsh discipline to make sure they obeyed orders once enlisted. The politicians and the press sold the abstractions, while the military punishment machine imposed the discipline. As Brigadier General Crozier said:

‘I, for my part, do what I can to alter completely the outlook, being and mentality of over 1,000 men… Blood lust is taught for the purpose of war, in bayonet fighting itself and by doping their minds with all propagandic poison. The German atrocities [many of which I doubt in secret], the employment of gas in action, the violation of French women, the “official murder” of Nurse Cavell, all help to bring out the brute-like beastiality which is necessary for victory. The process of “seeing red” which has to be carefully cultured if the effect is to be lasting, is elaborately grafted into the make up of even the meek and mild…The British soldier is a kindly fellow, it is necessary to corrode his mentality.’6

Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig said that moral fibre was essential in all men under his command. Those who had little or none of this attribute needed to know the daily fear of punishment. Major General Childs stated that harsh punishment was necessary to compensate for the loss of the old regimental spirit, which was lost with the decimation of the ‘Old Army’ in the battles of 1914/15. Perhaps if 19th century generals hadn’t ordered umpteen thousands of men across no-man’s land into a murderous hail of gunfire produced by 20th century technology then the men and their spirit might have survived. The lessons of war seemed to have passed some of the officer class by, including Haig. In 1926 he commented:

‘I believe that the value of the horse and the opportunity for the horse in the future are likely to be as great as ever…aeroplanes and tanks…are only accessories to the man and the horse, and I feel sure that as time goes on you will find just as much use for the horse, the well-bred horse, as you have ever done in the past.’

He was, perhaps, influenced by the Cavalry Training Manual of 1907. It stated:

‘It must be accepted as a principle that the rifle, effective as it is, cannot replace the effect produced by the speed of the horse, the magnetism of the charge, and the terror of cold steel.’

Before looking at the treatment of those charged with serious offences such as desertion let’s take a look at the punishments doled out in the field by the disciplinary machine. The Rules of Field Punishment, approved in 1907, were applied to both the Army and Royal Marines. There were two types of field punishment, No. 1 and No. 2. The only difference was that under No. 1 the prisoner was liable to be tied to a fixed object. The punishments could be awarded by a court martial or a commanding officer, and were regularly given out for fairly minor offences. The troops called Field Punishment No. 1 ‘the crucifixion’. The prisoner was tied with handcuffs, straps or ropes to the wheel of a gun or a wooden T-bar construction. With the wheel he would be secured in the X-position, with the T-bar he would be held in the T position, with his arms tied to the horizontal post and his feet secured to the base of the vertical one. The punishment could be spread out over a number of days, so if the soldier was given 12 hours No. 1 he could be tied up for two hours a day until his time was completed. In regards to No. 2, one version I have come across involved a man being made to hold two buckets of water for a period of eight hours. Whether this was done in two-hour blocks, I don’t know. The application of one and two varied, depending on the whim of the officer ordering the punishment. It has been claimed that some men were placed in site of the enemy when undergoing their punishment. Blindfolds could also be used. One officer justified their use by saying ‘it was to stop the prisoner from making insolent grimaces when an officer walked by.’ If a soldier’s unit was going into action then his punishment would be suspended until he returned, if he did return.

It was said that these punishments prevented troops being sent back behind the lines to serve time in prison, thereby keeping troop numbers up to strength. Private W. Underwood of the 1st Canadian Division, who was sentenced to seven days No 1, described it thus:

It… ‘consists of being tied on a wagon wheel. You’re spread-eagled with the hub of the wheel in your back, and your legs and wrists handcuffed to the wheel. You’d do two hours up and four hours down for seven days, day and night. And the cold! It was January 1915, a really cold month, and when they took you down they had to rub you to get the circulation going in your limbs again. And the only reason I was there was because I missed roll-call.’7

What it did for the poor sod's moral is not known.

The main system for the dispensing of military justice was the courts martial. In peace-time the General Court Martial was the highest judicial body within the military machine; it consisted of five or more officers, who were usually backed up by a legally qualified judge-advocate. In the theatres of war, except for the trial of officers, most serious cases were dealt with by Field General Courts Martial (FGCM). These were less formal and easier to convene. The Rules of Procedure for an FGCM stipulated that at least three officers should sit on the bench and that the president should hold the rank of Major or above, this was not always possible so occasionally a Captain would preside. A judge advocate could be appointed to assist the bench but this rarely happened. The prosecution in an FGCM was usually carried out by the accused soldier’s adjutant. His defense would be put forward by a junior regimental officer, who would be referred to as the ‘prisoner’s friend’. So, a colleague of the prosecutor, a fellow mess mate or possibly an old school chum, would be charged with saving the accused from the firing squad. Even if the prisoner knew of a civilian barrister, it would have been nigh on impossible to secure his services. Under military law a civilian lawyer could only appear at a court martial outside of the UK if he had the permission of the Army Council.

Under the rules of procedure the accused must be given the opportunity to prepare his defense, ‘and must have the freest communication with his witnesses which was consistent with good order and military discipline and with his own safe custody.’8 The reality of war, though, isn’t about rules of procedure, it is about mass destruction, terror, seemingly endless bombardments and the panic inducing clouds of toxic gas as they drift across no-mans land. So is it any wonder that in many trials there was little in the way of proper defense; the mental state of the accused and the inability of the defending officer to adequately put forward the prisoner’s case were serious impediments to a fair trial. On too many occasions the defending officer lacked knowledge of law and procedure; and the chaos and confusion on the front line meant that often it was impossible to contact or identify important witnesses.

In his novel The Secret Battle, A.P.Herbert drew on his wartime experiences as an army officer; he was called on at various times during the war to use his knowledge of jurisprudence as a defender, and sometimes as a prosecutor. Although the Rules of Procedure state the ‘prisoner’s friend’ should have all the rights of a professional counsel the narrator in The Secret Battle described the difficulties the officer for the defense came up against:

‘Many courts I have been before have never heard of the provision; many having heard of it, refused flatly to recognise it, or insisted that all questions should be put through them. When they do recognize the right they are immediately prejudiced against the prisoner if the right is exercised. Any attempt to discredit or genuinely cross-examine a witness is regarded as a rather sinister piece of cleverness; and if the Prisoner’s Friend ventures to sum up the evidence in the Accused’s favour at the end – it is often “that damned lawyer stuff”’.9

On 24 August 1914 the British Commander-in-Chief received information that the French armies on his immediate right were in the process of withdrawing, thus leaving exposed the whole of his southern flank. He decided to order the British Expeditionary Force’s or BEF to retreat from Mons, it continued until the 5th September, when the BEF drew up in a defensive line to the southeast of Paris. The British Official History stated:

‘They were short of food and sleep when they began their retreat; they continued it, always short of food and sleep, for thirteen days. During this time they covered a distance of about 200 miles, and in the constant fighting almost 20 thousand were killed, wounded or missing.’

The day after the retreat was halted, the first British soldier to be executed during the war, was court-martialled.

He was nineteen at the time. Although a member of a Home Counties regiment, he had enlisted in Dublin in February 1913 at the age of seventeen. He was discovered hiding in a barn in the early hours of the 6th. When asked what he was doing there it is alleged he replied, ‘I have had enough of it. I want to get out.’ He was tried on that day with little time to prepare a defense. The FGCM consisted of a Colonel, a Captain and Lieutenant. It is not known whether or not he had an officer to defend him. No address in mitigation of sentence was made on his behalf and the court sentenced him to death. It is doubtful, given the army’s attitude towards psychiatrists and psychologists, if any inquiries were made into his mental state. The sentence was confirmed that evening by the Commander-in-Chief Sir John French. Two days later at 6.30am the soldier was told the findings of the court martial and that the sentence of death had been confirmed. Within 45 minutes he was taken before a firing squad and shot. He wasn’t old enough to vote, but he was old enough to be executed.

Six days later, on the 14th of September, Army Routine Orders revealed that the commanding officers of two infantry battalions had been convicted of a charge of ‘behaving in a scandalous manner unbecoming to the character of an officer and a gentleman’. During the retreat from Mons, it was stated, they had agreed together, without due cause, that they were prepared to surrender themselves and their men to the enemy. They were not sentenced to be executed they were cashiered, that is they were dismissed from the army in disgrace.10 One law for the officer class and another for the rank and file.

The lower age limit for joining the army in the early days of the war was nineteen, this was reduced to eighteen-and-a-half mid-way through the conflict; though some as young as sixteen enlisted. In the hysteria whipped up across the country at the outbreak of the war, confirmation of age was not as thorough as it should have been. The same applied at the other end of the age-limit, men over forty were being admitted into the military. Not only were the recruiting stations lax over age but also in regards to mental and physical health. There were men with histories of mental breakdown, including periods of confinement in mental institutions, who were allowed to enlist. As were men who were both mentally and physically unfit for combat. A medical examination board system was introduced at the end of 1915, but even then the examinations continued to be of a cursory nature, with each board expected to examine 200 recruits a day. This might seem strange when you consider the attitudes of the ruling class and senior military officers towards the working class in the period immediately prior to the war. But it was, ‘war, me lads’, so the residuum, the unpatriotic trade unionists and the unstable town-bred masses were welcomed with open arms.

It has been argued that many of those put before a court martial were suffering from shell shock at the time of their trials; though considerations of the impact of such traumas on the accused men left a lot to be desired. Some fifty years after the war a former captain recalling his time in a Scottish regiment wrote:

‘Psychologists, sociologists and the like had not yet been invented so there was no pernicious jargon to cloud simple issues. Right was right and wrong was wrong and the ten commandments were an admirable guide… A coward was not someone with a ‘complex’ [we would not have known what it was] but just a despicable creature… Frugality, austerity, and self-control were then perfectly acceptable. We believed in honour and patriotism, self-sacrifice and duty, and we clearly understood what was meant by a gentleman.’11

The figures for those executed during the war have been a matter of argument since the war ended. Judge Anthony Babington, in his book ‘For The Sake of Example’, put the figure at 304. Some 2,600 other death sentences were passed but not carried out, the soldiers serving various terms of penal servitude. Of those executed only three were officers. The number of summary executions is not known and not all formal executions made their way on to the records, so even Babington’s detailed examination is open to contention. In his excellent pamphlet Mutinies: 1917-1920 Dave Lamb puts the figure at 306, and the figure 324 has been quoted in some other publications, but that last figure is for the period 4th of August 1914 to 31st of March 1920. And these figures ignore the 700 odd Indian soldiers who were executed.

And in the period between September and the end of December 1917 at least 13 members of the Labour Companies were summarily executed for going on strike, and a further 38 were wounded. Despite such reprisals, strikes amongst labour companies continued to occur. The companies were made up of civilians, but they came under military discipline. There were some 200 thousand men in the Chinese labour companies alone. They built and repaired roads and railway lines and also worked on the docks of the Channel ports. The companies also employed Fijians, Maoris and Egyptians amongst others. Racism undoubtedly played a major part in the treatment of men in the companies; black South Africans were kept segregated from those human beings ‘classified’ as Cape Coloured. The men lived in tented areas surrounded by barbed wire and patrolled by armed guards. In regards to the Chinese workers, Lamb says that ‘there was substantial syndicalist influence amongst them…They formed several unions, and between 1916 and 1918 they were involved in at least 25 strikes.’ Being subject to military law the strikes would have been regarded as mutinies. Lamb points out that on returning to China after the war the men set up 26 trade unions in Canton, these were regarded as the first modern unions in China. And in Shanghai a syndicalist group was formed called the Chinese Wartime Labourers Corps.

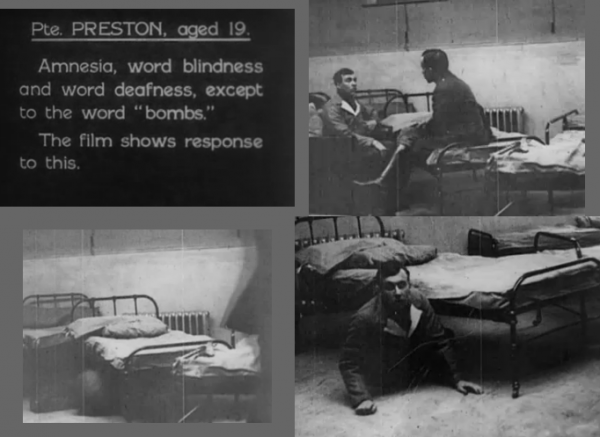

Images taken from ‘War Neuroses: Netley Hospital,1917. Seale Hayne Military Hospital, 1918.’ Wellcome Trust 2008, CCBYNC

During the first two months of 1915 fourteen soldiers were executed on the Western Front, thirteen for desertion and one for quitting his post. Two of the fourteen were a Lance-Corporal from a Yorkshire regiment and a young private from an Irish regiment. The Lance-Corporal had been recommended for mercy by the court because of his previous good service in action and his excellent good character. Unfortunately, for him, the Commander of the second army of the BEF, General Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien, announced that as no executions had been carried out in the soldier’s division, an example was required to stress the seriousness of desertion. The Irish private, who had been in the front-line trenches for some three months, gave as his reason for going absent a letter he had received from home, which told him that his two brothers had been killed in action.

The swiftness of the judicial process seen with the first execution did not become the norm. On many occasions it went thus: When both sides had put their case the court was closed whilst the members considered their findings. The court reconvened when a decision had been reached. If the verdict was not guilty it was declared straight away, if it was guilty the president of the court stated that it had no findings to announce and they proceeded to hear evidence with regards to the prisoner’s character. The reason why no announcement was made after a verdict of guilty was that neither the conviction nor the sentence became official until they were confirmed by the proper confirming authority. For capital offences this authority was the Commander-in-Chief of the area in which the offence took place. When a death sentence had been confirmed by the C-in-C the announcement of the decision usually took place before a special parade of the condemned man’s unit on the evening before his execution, the prisoner would be in attendance. Sometimes, though, this fucking performance would be put off until the morning of the poor sod’s execution. The time between the decision to execute and its announcement usually varied between nine and sixteen days, it could, though, extend to a month or more.

In 1921 during the committee stage of the annual Army Bill a debate on courts martial took place in the House of Commons. A contributor to the debate, Major M. Wood, who had considerable experience of the courts martial in the BEF, stated the he found some courts to be utterly incompetent. He said that it was a scandal to ask such a court to adjudicate upon any case whatever. Major Wood exposed the bind that some of those found guilty ended up in. A major he had spoken to explained his attitude when sitting on a courts martial: Whenever he was involved he always imposed the maximum sentence laid down by the Army Act so that the confirming authority could reduce it if necessary. Wood also spoke to a confirming officer, who said that he never reduced a sentence, because he considered that the members of the court had actually seen the witnesses and were in a far better position than he was to assess the proper punishment for the offence.12 To paraphrase the old saying: The prisoner was damned if they did and damned if they didn’t. Whether a man was shot or imprisoned seemed to depend on one of two factors: Did he have the makings of a good soldier or would the execution be beneficial with regards to army discipline.

Many of the soldiers charged with desertion and other death penalty offences pleaded that they had been suffering from shell shock when the ‘offence’ took place. The term ‘shell shock’ was in common use among squaddies fighting in the war, but it didn’t enter the medical lexicon until February 1915. The man who put it there was the Cambridge psychologist C.S. Myers, who had been working at the base hospital at Le Touquet. The term seemed to reflect the reality that faced the army’s medical officers. Men who displayed no physical evidence of injury were turning up at the medical facilities manifesting clear signs of distress.

‘These soldiers were not wounded, yet they could neither see, smell nor taste properly. Some were unable to stand up, speak, urinate or defecate; some had lost their memories; others vomited uncontrollably. Many suffered from the shakes…Some developed unnatural ways of walking.’13

No one was certain as to how the symptoms were created, but many had opinions and didn’t hesitate to voice them. Within the military, as noted above, some officers regarded shell shock as another term for cowardice. In the world of medicine, opinions sat on two sides of the fence. The neurologists argued that shell shock was caused by damage to the soldier’s nervous system, while the psychiatrists argued that the manifestations had their roots in severe emotional shock.

Despite Haig’s faith in the horse, there can be no argument that the battlefield had undergone a technological revolution. Between the wars of the late 19th century and WWI advances in chemistry had produced new types of explosives that were cleaner and more powerful than gunpowder. These advances allied to improvements in the efficiency of the guns themselves meant that more accurate and sustained bombardments became the norm, and the range of the guns increased. This revolution had produced a different way of fighting. By 1915 the armies on both sides of no-mans land had settled into trench warfare. Because of the developments in weaponry this meant that the men in the trenches were sitting ducks. An understanding of what those in the trenches on both sides of no-mans land underwent can be garnered from the following figures: Over 170 million artillery shells were fired by the British. In the first two weeks of the third battle of Ypres 4,283,550 rounds were fired at a cost of £22,211,389 14s. 4d. To bring that down to a more comprehensible number; in a light barrage you could expect about half a dozen shells to land in the vicinity of your trench every ten minutes, and in a heavy bombardment twenty to thirty shells would be landing in a company sector every minute.14 And the decisions of the military hierarchies to counter the artillery bombardments by going on the offensive with charges across the open land between their respective forces produced casualty figures that could be mistaken for the attendances at major football matches. On the first day of the Battle of the Somme, the 1st of July 1916, the British Army lost 57 thousand men, more than a third of them were killed. By August the 2nd some 200 thousand British soldiers had been killed or wounded. The technology of the artillery had improved and so had that of the machine gun; 20th century technology and 19th century generals, a deadly mix forcibly swallowed by those on the front line. Is it any wonder that some broke down.

Because many of those who broke down were officers there was less talk of degenerates and weaklings. Although when officers broke down and were removed from the line there was a euphemism used to describe the removals, it was ‘sir has gone on a course’; there must have been many courses going on. It is estimated that some 24 thousand cases of shell shock were sent back to England in the year ending April 1916, and a total of 80 thousand went back during the four years of the war. Within the 500 thousand American troops engaged in the war 10 percent were returned to the USA suffering from shell shock. In 1917 special treatment centres were set up in France, but in England the system still struggled to cope. On arriving in England patients were supposed to be processed through clearing hospitals and then on to specialist centres, but more than half of them ended up in general military hospitals, often without their medical notes. These were hospitals where the overwhelmed medical staff had no psychiatric training. There was also a lack of consistency in the treatments; it depended on which hospital you ended up in. You could be put through a disciplinary system involving physical exercise or treated to the Weir Mitchell method of isolation, rest and a milk diet. And some patients were simply left to their own devices. According to the American psychiatrist Thomas Salmon there was ‘no more pathetic sight’ than the mismanaged nervous and mental cases crowding the military hospitals.

‘They were ‘exposed to misdirected harshness or to equally misdirected sympathy, dealt with at one time as malingerers and at another as sufferers from incurable organic nervous disease…many enter[ed] the hospitals as ‘shell shock cases’ and came out as nervous wrecks.’15

When it came to treatment class reared its head, officers and men went to different wards and hospitals and the levels and types of treatment differed. Squaddies could end up under the care of asylum doctors who, according to C.S. Myers, were deeply conservative and lacking in intellectual curiosity. Among them the dominant attitude was that mental illness was physical, hereditary and untreatable; this gave them a fatalistic outlook in regards to shell shock patients, who were regarded as inferior and bound to break down. This broadly unsympathetic view coupled with an eagerness to return as many cases as possible to civilian life meant that thousands were sent back to their home towns, where none of the facilities required for effective treatment existed. They were left to rot, many became incapable of living a normal life.

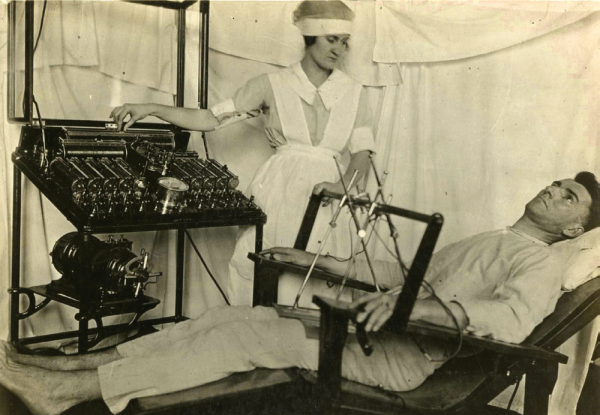

A shell-shocked soldier receives an electrical shock treatment from a nurse. (otis historical archives)

In the period late 1916, early 1917, different approaches started to develop. Centres specifically allocated for the psychological treatment of shell shock were opened, although the class division was maintained. Another approach was developed that involved the application of pain. This was developed by Edgar Adrian and Lewis Yealland. Adrian was not long out of medical school and Yealland was a Canadian evangelical Christian; their methods were described by some as sadistic. They believed that a weakness of will and intellect combined with hyper-suggestibility and negativism were the components of a hysterical type of mind. Adrian thought that psychoanalysis of such men would be time consuming so he and Yealland’s preference was for ‘a little plain speaking accompanied by strong Faradic current.’ In other words they electrocuted the poor bastards.

‘The current can be made extremely painful if it is necessary to supply the disciplinary element which must be invoked if the patient is one of those who prefers not to recover, and it can be made strong enough to break down the unconscious barriers to sensation in the most profound functional anaesthesia.’16

Adrian and Yealland went their separate ways at the end of 1917. Yealland continued to ‘cure’ soldiers who came under his tender mercies. One poor sod had suffered harsh treatment before Yealland got his hands on him. The man had collapsed in Salonika and when he came to five hours later he was unable to speak and was shaking all over. He was given strong electrical charges to his neck and throat; lighted cigarettes were applied to the tip of his tongue and hot plates were placed at the back of his throat. Nine months later after much ‘treatment’ he was put into the care of the evangelical Christian Yealland, who started to drive the devil out. The man was taken to a darkened room and told that neither he nor Yealland would leave until he was cured. He was given a burst of electricity to the back of his throat that made him jump backwards. After four hours of having electrical shocks to his throat and limbs the patient was seemingly ‘cured’.17

Adrian, Yealland and others, like Arthur Hurst, who applied forcible manipulation to his patients’ limbs, a treatment that caused considerable pain, were great self-publicists. Adrian, though, reflected on the treatments he and Yealland had doled out. With the loss of the symptom, which preserved their self-respect, there would soon be a revival of anxiety and there was no certainty that the patient would not break down again if he went back to his unit. Adrian turned away from the supposed cures of the physical symptoms and with others addressed the underlying psychological causes. But how much electrical current passed through how many bodies before he turned down another path?

Soldier's hospital

This photograph shows the University of Birmingham’s Great Hall converted into a military hospital ward

Let’s take a brief look at two of the treatment centres set up in Britain for those suffering from shell shock, centres that took a psychological approach to the problem. The most well known was Craiglockhart, situated just outside of Edinburgh, it was one of six reserved for officers. It was where the poets Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfred Owen met. Another one, less well known, was Maghull, located just outside of Liverpool. It was for rank and file soldiers, and had originally been for epileptics, but was taken over early in the war by the War Office as a treatment centre to which ‘borderline’ and ‘mental cases’ could be sent without incurring the stigma of the asylum.18 It was the nearest place comparable to the centres provided for the officers that rank and file soldiers encountered. Maghull was staffed by doctors who did not regard their patients as craven cowards. They were open to the ideas and theories of Dejerine, Janet and Freud and were keen to draw on them in the treatment of the 600 or so men resident at the hospital. The soldiers were treated with sympathy. Interest was shown in their symptoms and they were encouraged to discuss their emotions, fears and dreams, just like the officers at Craiglockhart. William Rivers, a Fellow of the Royal Society and a doctor with experience in a wide range of medical disciplines, said that ‘patients dreams at Maghull furnished confirmation of Freud’s view that dreams have the fulfilment of a wish as their motive.’ He found, though, that soldiers were often reluctant to reveal dreams. He also concluded that ‘the dreams of uneducated people are exceedingly simple and their meaning is often transparent.’ Presumably, when he transferred to Craiglockhart, he found a better class of dreams to analyse! What he didn’t understand was that the soldiers in Maghull felt that the professed interest in their dreams was part of a plan to get them back to the front line, so they were wary of fully opening up about their nighttime travails.

One of the differences between Maghull and Craiglockhart was in the area of physical exercise. The men at Maghull were encouraged to do remedial work on the hospital’s farm, while up on the outskirts of Edinburgh the officers partook of the sporting opportunities on offer. These included badminton, bowls, cricket, croquet, golf, tennis and water polo in the heated swimming pool. Nighttime, though, eroded the enforced class differences. Despite Rivers’ view of working class dreams, the nightmares that invaded the sleep of the squaddies thought nothing of visiting the slumbers of the officers in the ‘Italianate pile’ that was Craiglockhart. And Sir raved and sleep-walked just like Tommy Atkins. Fear and terror – the great democrats.

The war officially ended with the Treaty of Versailles, but the other war that had rumbled on throughout the period, the class war, raised its head. Britain saw 43 strikes break out within the military following the Armistice, including five in the navy. The main grievance was about delays in demobilisation; Lloyd George had made promises of immediate demobilisation in the election campaign that followed the Armistice in a desperate attempt to win votes. Plans to send troops to fight in Russia against the Bolsheviks also influenced matters, as did antagonism towards officers and the harsh systems of punishment that were doled out. Bad food and poor living conditions were also factors. A brief look at some of the strikes will give a sense of the level of discontent within the rank and file.

In Folkestone the announcement, on the 3rd of January 1919, that men were to be sent back to France kicked things off. The Daily Herald reported it thus:

‘On their own signal, three taps of a drum, two thousand men, unarmed and in perfect order, demonstrated the fact that they were fed up, absolutely fed up. Their plan of action had been agreed upon the night before: no military boat would be allowed to leave Folkestone for France that day or any other day until they were guaranteed their freedom… Pickets were posted at the harbour. Only Canadian and Australian soldiers were to be allowed to sail, if they wanted to. As a matter of no very surprising fact they did not want to… Meanwhile troop trains were arriving in Folkestone with more men returning from leave and on their way to France. They were met by pickets, and in a mass they joined the demonstrators. On Saturday a great procession of soldiers, swelled now to about 10,000, marched through the town. Everywhere the townspeople showed their sympathy. At midday a mass meeting decided to form a soldiers union. They appointed their officials and chose spokesmen.19 A War Office official, Sir William Robertson, came down from London and conceded the men’s demands. Complete indemnity was promised.’

The Daily Herald declared:

‘Everywhere the feeling is the same, the war is over, we won’t have to fight in Russia, and we mean to go home.’

In Dover another 4 thousand troops demonstrated in support of the Folkestone men. On the 8th January delegates from Folkestone and Dover arrived in London, with delegates from other camps. Lamb says that it was the first overt sign of the growth of rank and file links. That same week saw militant resistance spreading with strikes taking place in Aldershot, Bristol, Fairlop, Grove Park, Kempton Park, Park Royal, Shoreham and Sydenham. While in Osterly Park in Isleworth more than 1,500 men of the Army Service Corps seized lorries and drove them to Whitehall. The men believed that they were going to be the last to be demobilised, but they had other intentions, and within four days they had all been demobbed.

There was fear within the government that these strikes could spread and link up with the strike movement that was spreading amongst industrial workers at the same time. Not that peace had reigned in industry during the war, according to the government’s 18th Abstract of Labour Statistics, 1918. In the period 1916-1918 a total of 2,264,000 strikes had taken place, and 13,968,000 working days were lost. This was despite thousands of workers being jailed or fined for breaches of the 1915 Munitions Act. Commanding officers were instructed to send in reports on the state of play in their regiments. They had to report on the attitude of the troops towards the Russian situation and also to monitor any signs of trade union organising within the ranks. The strikes lead to the speeding up of the demobilisation process and undoubtedly helped to foreshorten Britain’s involvement in Russia, much to the chagrin of Churchill.

On returning to civilian life the men found that retail prices had more than doubled in the period from July 1914 to November 1918, and real wages in mid-nineteen eighteen were 75 percent of their 1914 level. And in all those countries where there had been an organised lowering of living standards to pay for the war, a virulent epidemic of ‘Spanish Flu’ wiped out thousands. In Britain 7 thousand died of it in November 1918 alone. Things were somewhat different for the capitalist class, though. Despite legislation that was supposed to keep a lid on profits, enormous amounts of money were made. A Liberal peer, speaking in the House of Lords in February 1919, made the point that ‘the most amazing profits Britain ever made, over £400 million, were made owing to the war.’20 Just one set of figures may go some way to confirming ‘oh what a lovely war’ the capitalists had. Before 1914 annual provision of shovels and spades to the British Army was 2,500, but from August 1914 until the end of the war 10,638,000 were bought.21 As one newspaper put it ‘the conduct of a modern war is simply a form of business’. And the government seemed to agree, because the formation of the Ministry of Munitions in June 1915 was ‘from first to last a businessman’s organization’.22 Over ninety directors and managers of large industrial firms were loaned to the ministry for the duration of the war, their companies often keeping them on the payroll at the same time. In the Ministry it was difficult to see where business control ended and state control started.

And what of the shell shocked soldiers and their families? The end of the war didn’t bring peace for them, because they had to fight on the pension terrain against the class based prejudices of civil servants in the Ministry of Pensions.

‘There are some men who funk or dislike military service to such an extent that it sends them off their heads. It is a tall order… for the state to take on the liability to support, possibly for life, a man who becomes a lunatic because he is a coward and fears to undertake the liability which falls upon him as an Englishman.’23

No doubt said from behind the safety of an office desk.

Very little has been said about the impact of shellshock on the women who were the wives and mothers of soldiers. Hidden from history, as Sheila Rowbotham said. Just think about it… the work load placed upon their shoulders. They were at once the carers, child minders, cleaners, cooks, factory workers, mediators, nurses, punchbags, rejected lovers and representatives at pension tribunals; and all before the advent of the welfare state. Some idea of how it was may be gleaned from the experiences of women who were the partners of Vietnam War veterans:

‘As the wife of a Vietnam combat vet, I have lived through many crises. My husband has suffered from the usual symptoms, the flashbacks, the nightmares, the emotional numbing and the rage reactions… I could also expect that sooner or later, I would be up all night holding him… In the past 15 years, Dave has held over 20 different jobs. If it weren’t for my working, our family could not eat. In between his ‘Vietnam attacks’, as I call them, however, he is a loving man. But he is scarred, emotionally and physically, and I blame the war for this and society for this also. If it weren’t for me he would have no one.

Over the years I’ve lost touch with my parents and brothers. I’ve also lost myself. I don’t even know how I feel anymore. Maybe I’m depressed; maybe I’m not. All I know is that I must keep functioning. My family depends on me… So I guess I’m Dave’s therapist and most of my life is organised around arranging his life to be as comfortable and stress free as possible.

Don’t ask me what it means to be a woman anymore. My life is too hard, and I’m too bitter, and too afraid of the anger and the pain inside me. I’m also afraid that someday my husband’s depression will engulf him, that I will lose him entirely to that sad far-away look in his eyes, to that ‘other woman’ Vietnam.’

Laura, wife of a Vietnam combat veteran.24

The above is taken from Aphrodite Matsakis’ book Vietnam Wives. One reviewer said it was ‘a profoundly moving book on the psychological and social consequences of war for families.’ There are many such stories in the book. If someone had been there to collect them, how many such stories would have been told in the years after 1918? WWI didn’t end with the signing of the Treaty of Versailles; not for the shell shocked; not for their wives and families… it just moved from a physical battle in the fields of Flanders to a psychological war of attrition in the living spaces of homes unfit for heroes.

But War – as war is now, and always was:

A dirty, loathsome, servile murder-job:-

Men, lousy, sleepy, ulcerous, afraid,

Toiling their hearts out in the pulling slime

That wrenches gum-boot down from bleeding heel

And cakes in itching arm-pits, navel, ears:

Men stunned to brainlessness, and gibbering:

Men maimed and blinded: men against machines-

Flesh versus iron, concrete, flame and wire:

Men choking out their souls in poison gas:

Men squelched in to the slime by trampling feet:

Men, disembowelled by guns five miles away,

Cursing, with their last breath, the living god…

Gilbert Frankau25

Lest we forget…

Biography

Brian Ashton <brian.ashton00 AT gmail.com> is an ex-car industry shop steward who has a long term interest in the military. This interest stems from three and a half fractious years in the British Army.

Footnotes

A version of the footnotes can be found on the Mute references held on Zotero, https://www.zotero.org/groups/mute/items/collectionKey/22QEW7N8

Zotero is a free and open source citation management system. Zotero allows many media types to be referenced and is designed for collaborative knowledge work and interoperability with other bibliographic systems.

1Bob Holton, British Syndicalism 1900-1914, London: Pluto Press, 1976, p.73.

2Ben Shephard, A War of Nerves, London: Pimlico, 2002, p.19.

3Ibid., pp.17-18.

4Ibid., p.18.

5Ibid., p.18.

6David Lamb, Mutinies 1917-1920, Solidarity Federation, 1977, p.3.

7Max Arthur, Forgotten Voices of the Great War, London: Embury Press, 2002, p.69.

8Anthony Babington, For the Sake of Example, London: Leo Cooper in association with Secker & Warburg, 1983.

9Ibid., p.14.

10Ibid., p.6.

11Shephard, A War of Nerves, p.25.

12Babington, For the Sake of Example, note 10, p.22.

13Shephard, A War of Nerves, p.1.

14John Ellis, Eye-Deep in Hell, Purnell Book Services, 1976, p.62.

15Shephard, A War of Nerves, p.15.

16Ibid., p.77.

17Ibid., p.78.

18Ibid., p.80.

19Lamb, p.9.

20Andrew Rothstein, The Soldiers’ Strike of 1919, The Journeyman Press, 1980, p.6.

21John Ellis, Eye-Deep in Hell, p25.

22James Hinton, The First Shop Stewards’ Movement, London: Allen & Unwin, 1973, p.29.

23Peter Barham, Forgotten Lunatics of the Great War, New Haven:Yale University Press, 2004, Epigraph 2.

24Aphrodite Matsakis, Vietnam Wives, Lutherville, MD: The Sidran Press, 1996, pp.9-10.

25John Ellis, Eye-Deep in Hell, p.17.

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com