The Body is Evidence

In his review-collage of Forensis, a book of essays accompanying the recent Forensic Architecture exhibition at Berlin's Haus der Kulturen der Welt, artist Martin Howse discovers not only the materiality of crime-scenes, but of all architecture, to be implicated in death

Object

[The World is] made up of compost of the millions and millions who have died and are blowing about. The dead are blowing in your nostrils every hour, every second you breathe in. It’s a macabre way of putting it, perhaps; but anything that’s at all accurate about life is always macabre. After all, you’re born, you die.

– Francis Bacon1

When life depends on it, you use asbestos.

– From an Asbestos advert2

Bartered, ingested, burnt and inhaled, sold, reproduced, snagged, rubbed, brushed with stiff wires, baked, scorched, left in the sun, buried in hot sand and later recovered, flushed many times, soaked in oils, measured, stained by lengthy close contact with various metals, set adrift, tossed from a car, left out in the rain, preserved by chemical means, bound, carressed, dried, frozen, ground up and sniffed, shaved, dusted with various powders, ripped, shredded, dipped in an acidic solution, dropped from a height, subjected over a long period to a heavy concrete weight, reversed over by a truck, bound tightly, cast and re-moulded, set on fire so as to analyse its chemical composition through study of the spectrum of these flames, crumpled or buckled from a falling back on its own provoked weight, subjected to small internal chemical changes which may cause a blistering under certain environmental constraints, fractured, stowed in damp conditions for a long period, dumped in the desert.

This is a list which could continue more or less indefinitely, a list of actions undertaken on an object, the book Forensis for example, equally prompting this list which inspires a future of forensic acts (aestheticised naturally), or the body which is here and now writing and talking, considered as living, discussed as belonging to some one (the body proper), to a self (properly named, constituted or qualified as a victim, an academic, as lowly paid, worker, survivor) with rights in engagement with both the earth (resources) and that body, rights often defined by their lack, their obstruction and infringement. As Thomas Keenan argues, within the pages of Forensis, the work under review.3

People routinely are not treated the way we might expect them to be – they are tortured, trafficked, enslaved, targeted, disappeared, murdered, censored, exploited and discriminated against [...] human beings are not treated as humans.4

In this second list (beginning to define a forensic aesthetics, writing as driven through these lists), the human always comes to be treated almost as an object. Is this 'the architecture of public truth'?

[...] the bones of a skeleton are exposed to life in a similar way that photographic film is exposed to light. A life, understood as an extended set of exposures to a myriad of forces (labor, location, nutrition, violence and so on), is projected onto a mutating, growing and contracting negative, which is the body in life.5

And under Forensis, it is precisely as objects, not quite as delicate as photographic grains of silver, that these ground up, machinic or enslaved bodies, come to speak, to be read out here. This ventriloquising prosopoeia ('Let the bones speak for themselves'), with a problematic relation to animism which un-nerves the work of Forensis, is underlined as an interpretation, a persuasive aesthetics. Forensis thus oscillates dangerously within the feedbacking of these two solely operational terms: 'a contested object or site, [and] an interpreter tasked with translating 'the language of things.'6 An interpreter who can talk on behalf of those things, which (who?) may or may not have been or be human, and thus can or cannot be operated on within forums which attempt to provide rights for these humans (and for nature, for the sea, for the earth under new legislations). Within a site or a scene which reveals as a stated secret the transparency of so many engineers and scientists now simply providing a mise-en-scene, a staging or re-staging, a re-presentation of the skeletal truth which can be used as a tool, an avenging arm against the violence of the (always at war) state and corporations.

The exposed image of Forensis materially fogs or becomes muddied through contact with the bones and earth which define it, rubbing against and between 'the animation of material objects and the gatherings of political collectives.'7

Yet within this material turning which Forensis commemorates, how could the words themselves, language itself, that interpretation be subjected to those listed actions, words to be buried in the snow for years, disinterred and made to speak (of) its own suffering?

Just as the 'meaning of' the word 'forensic', grounded in 'forensis', that underlined 'pertaining to the forum' where a case might be presented in Roman times, has been eroded, subject to an attrition or an accumulation of dust, as it comes to refer solely to a forensic science, a Crime Scene Investigation (CSI) re-presented in a court of law.

Forensis here returns as forensic architecture8 as both forum for the negotiation of public truth9 and as measurement or dissection, as both forensic aesthetics 10 and as architecture. The latter term here denotes that which pertains to the body and its buildings or territories, either living, primarily within an urban environs, or dead, interred or disinterred, crypted and de-crypted within:

primary mass graves.

robbed primary mass graves.

secondary mass graves.

robbed secondary mass graves.

tertiary mass graves.11

One side of Forensis is the courier's tragedy – that it is always the carrier of a message or truth for those that survive, that whosoever's body has no meaning which could become after all 'valuable', unless and after it is bagged and tagged and delivered up to a court. The courier bears up that written message which, at the moment of death, has mysteriously been changed to reveal the truth of that which has happened to those other bodies. The hair grown back over a tattooed message, is shaved to unveil a now differing truth (writing always as roofed in writing). But finally the truth is that there is no-body, the living or dead are subject to the same code of algorithm and measurement (design of a bomb shelter, plans for a slave ship) within an architecture of a violence to come that is forensic architecture.

Truth is not in the body, in the body of data, in a dead body being spoken for and the book is not a body, not like a body, the earth described and interpreted after its death there in the book which is not like the body. Words aren't buried, smashed, left to accummulate a thick treaty of ash-stained dust, perhaps just as huge numerals are carved in the desert and disappear.

Site

Accumulating, listing and acting in sites, forensic architecture becomes an obsession, to have to look for it again and again, to see through that lack of a before, that lack of a contemporary affect which marks the legal and actual experience of Forensis; its nature is to multiply traces, to antagonise death:

It was a sobering journey, generated in part by a conviction that making contact with the site and its remaining residents might somehow begin to supplement an event that the legal protocols of the court had, I felt at the time, systematically disarticulated and thus evacuated of all affect.12

The site is always a site of the return, of revisiting. In London, bodies suffered to the end of malnutrition, disease, poverty and plague, a black death of capital, were revisited and resubjected to a material dissolution, an alchemical inverse, as chemistry and acids leached through the soil from the workings of the Royal Mint erected on the grave site, now incorporated within the financial centre of the City of London. This process rendered the future work of forensic archaeologists all the more difficult; coherent DNA samples trickier to recover from a dissolved set of bones.

This revisiting is neither parable nor metaphor but that which literally is 'that which comes to happen as it is.' This being acted on again and again is primary within (intrinsic to, of the nature of) Forensis and forensic aesthetics, this before and after13 as a return, as a happening again; that the before is not discarded (the stone tape erased), that which is how it was, which is no more, but rather stands ahead, fore-saying that which is to come.

These ghost sites of revenance, of return, again multiply throughout Forensis as an atrocity exhibition of capital, of the earth exchanged both ways, and repeatedly with a body from which all value and resource can be extracted, a terminalist recovery; to be wholed up and spent exactly where?

The fairground both is and becomes a (living) deathcamp .14 The mine is a crypt, is a concentration camp, is a resource.15 The displaced (by war) are again and again revisited by 'autogenocide' operating on a twice ravaged terrain.16 Under the figuring of the earth as 'a corpus delicti'17 revenance as repeated extraction becomes a core modus operandi; who better to task with the 're-covery' or re-mediation of ecologies than those charged with their destruction 18.Simulations of nuclear winter morph into studies of climate change within a global balancing (cold war, warm war) which underscores the always doubled remove of nature from ecology (towards a darkened ecology).19

Under Forensis, it is not the dead who come back to haunt, rather we come back to haunt the dead over and over again as technological vampires, consecrating their earth to capital and finally disinterring their bodies to again bear witness (for who, for the survivors of this again and again) through technologies of Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) and 3D scanning.

Technology is always twice visited on the body in a doubled ex-huming or rather of a cycle of inhalation and exhumation:

When the Twin Towers collapsed tons of concrete, glass, furniture, carpets, insulation, asbestos, arsenic, benzene, benzopyrene, cadmium dioxins, fibreglass, gypsum, heavy metals, plastic, silica, PAHs, PCBs, smoke detectors, mercury and gold (from several thousand flourescent light bulbs), lead from thousands of computer monitors and titanium from the paint on the WTC walls, computers, and paper were reduced to enormous oxygen-poor debris that burned until December 19, 2001.20

A fire releasing metal-rich gases, a decomposition of these materials into fine particles which are later inhaled and thus incorporated by attendant bodies, the rescue workers and returning Wall Street workers, local inhabitants of lower Manhattan. Toxic architecture becomes toxic body, hinting at a truly forensic architecture to come, the conflagration.

And again, within the frenetic, algorithmically induced re-cycling which produces and is produced by that architecture:

It is clear that the toxic metals released from underground had circulated as transversal agents of contamination, from the body of the earth to the bodies of people. And, strangely, the image of arsenic slowly releasing itself from inside the body, rupturing the skin and changing its color is not too dissimilar from the images resulting from the remote sensing of the desert’s surface, evidencing how mining excavates and transforms the earth. In this case it is the body itself that becomes the symptom and evidence of a large-scale environmental contamination.21

The earth is a body subjected to a toxic, architectural violence, a body which, like all bodies has ceased to ever be a (transcendant) earth or body. A body which is precisely not evidence, as that which is made to speak and has rights (again, the contradictions of this deep sea ventriloquism).

And the body and/as the earth doesn't mime or parody a technological cycle, but this is what is acted upon it, what constitutes it (as an objective consciousness). It is not to ask whether certain technologies are or are not useful, are needed for a greater or common good. But to ask what are they truly of use for if not to recycle the dead, these revenants, to repeatedly exhume and make disappear the green men, los hombres verdes 22, these ecologically-minded vegetable deities absolutely mocking so-called cycles of nature and rebirth; rising from the earth in the spring, providing the wealth of a harvest, and then falling back into the earth under the sign and wreath of entropy.

Interpreter

They could have moved those people out of the building. They knew it was a target and they didn’t. [...] There’s no point – I mean there’s no way of waging war in a pretty way. It’s ugly. It’s an ugly business.23

The look of the world's a lie, a face made up

O'er graves and fiery depths; and nothing's true

But what is horrible. If man could see

The perils and diseases that he elbows,

Each day he walks a mile; which catch at him,

Which fall behind and graze him as he passes;

Then would he know that Life's a single pilgrim,

Fighting unarmed amongst a thousand soldiers.

– Thomas Lovell Beddoes. Death's Jest Book

Existence for all objects and bodies is a permanent war and the discrete terms of architecture, climate and environment repeat those forces which exert the any-body or any-object to a war of attrition which is not smoothed by any rights of subjecthood under any state (or are indeed purposefully manipulated as violent forces by the state). They are only subject to a dark calculus and a mesmeric algorithmics.

The language of Forensis and the law is a language of warfare, and thankfully the total ontology of warfare is object oriented.

All architecture is not just forensic in potential – as in always open to recording or being subjected to a violence – but always forensic from the beginning, as suggesting that violence; there is never an innocent architecture. It is the materiality and engineering of architecture which makes a fairground fairly able to function as a death camp, both adhering to Benthamic economies of visibility and of utility, a vicious calculus mopped around by rights. Again the contradiction of Forensis is to mute the material body with measurement and visibility, to un-earth it.24

The question remains as to what could constitute a truly forensic architecture or urbanism; miming intensely that coming after of forensics, coming after the incident which the ruins of course have suggested.25 Helene Kazan's essay 'What the war will look like', poses the question precisely.

Along what kind of a continuum could a mobile, forensic urbanism be conceived, allowing for the polite retention of the traces of any act, a secreted mineral shell which thus grows and fits to the body (it is that body) as of a mussel, crystalising external and ingested material, accumulating passengers and parasites.26

Or an architecture which encourages an aesthetics of forensics, perhaps as clichéd as pornography and tilting towards violence; the bunkers, multistories, highrise hotels, flyovers, and parking areas of Ballard; an architecture as framing and measuring the body, as a slave ship.27 Ballard's Crash is a precise and creative overlay of pornography and forensics at the level of architecture and of the body, the mineral shell as that extracted metal automobile carapace. But that's neither the place nor the point, rather all architecture should be considered as a site of execution (which is the law on the body) with all that this means in terms which point towards software as death.28

Easier options are suggested by the terms of a vampire architecture, of a Dresden inverted or reversed29, or of an architecture intended simultaneously for both the dead and for the living (not a crypt, nor mausoleum, nor a monument, not an alternative or underground catacombic city). The toxic body as house of the Benthamite auto-icon,perhaps?30 Finally, drawing near, and as the essay 'Breathing Space' within Forensis makes explicit, an architecture of smoke and of dust.

This is an unimaginable truly forensic architecture, that which always comes after as a conflagration; a funeral pyre for a not yet dead or dying alcoholic ex-sailor for example, celebrating any timed and ground (up) zero trace31, a fire of ones and of zeroes which somehow must always be of the digital, the record of that downed, drowned drone destroyed before and after in its pure extraction.

A conflagration of the forum which is and was always absolute.

Martin Howse <m AT 1010.co.uk> has worked collaboratively within ap, xxxxx and more recently micro-research, a mobile platform for psychogeophysical research with ongoing projects in Berlin, London, Suffolk and Peenemuende. Over the last ten years he has workshopped, performed, lectured and exhibited worldwide

Note (Image credits)

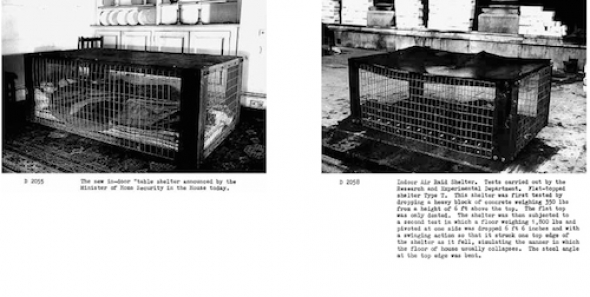

Indoor "table shelter" announced by the UK Minister of Home Security in 1940, featured in 'What the war will look like' by Helene Kazan. Sourced from the Imperial War Museum.

Photograph taken of a kitchen in Lebanon in 1989 and 2014, featured in 'What the war will look like' by Helene Kazan

Footnotes

1 This quotation, from Bacon's interview with Joshua Gilder, 'I Think about Death Every Day', Flash Art, May 1983opens Füsun Türetken's key essay 'Breathing Space: The Amalgamated Toxicity of Ground Zero', in Forensis: The Architecture of Public Truth, Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2014, p. 254.

2 Text from a poster or advert imaged within the essay Breathing Space mentioned above. Ibid, p.260.

3 What is this work called Forensis? Either defined in its own terms, that which is being spoken, starting with the subtitle 'The Architecture of Public Truth', read as the (aesthetic) creation of public truth within public forums and making use of material structurings, or defined as this object weighing a certain amount, occupying a certain (mobile) measured space, subject to those possible acts (according to a certain violence adhering to the popular idea of the forensic) and involving attrition and destruction in its creation, distribution and arrival here to be spoken of. Forensis is subject to its own aesthetics and definitions; this bony, bleached materiality which does not speak, but is rather spoken for. From here on I also capitalise Forensis as referring to concept, practice and book/object.

4 Tom Keenan, 'Getting the Dead to Tell Me What Happened', Forensis, p 42.

5 Keenan and Weizman, 'Mengele's Skull', quoted in Tom Keenan, ibid., p.40.

6 From Eyal Weizman's clear essay, Introduction: Forensis, Ibid, p. 9.

7 Ibid, p. 9.

8 The work re-presented here, Forensis, a collection of essays underwritten by Forensic Architecture, based at Goldsmiths, University of London. Equally the exhibition Forensis, presented at the HKW in Berlin as part of The Anthroposcene Project. That return and thus re-presentation is important: 'This book returns to forensis in order to reorient the practice of contemporary forensics and expand it. The aim here is to bring new material and aesthetic sensibilities to bear upon the legal and political implications of state violence, armed conflict and climate change.' Ibid, p. 9.

9 Again from the introduction: 'forensis seeks to perform across a multiplicity of forums, political and juridicial, institutional and informal.' Yet much of the book is a collection of forensic investigations and reflections on the world forensic is placed formally and firmly within, the frame of institutions either political or juridicial, forums underwritten by various NGOs, UN departments, legal offices, international courts and conferences. Indeed within the conversation The Architecture of International Justice, these forums are mapped and annotated with one question or caveat appended as follows: 'the current international judicial network seems to reproduce some of the spatial configurations of European colonialism.', ibid, p. 321.

10 A seeing and hearing, a judging on this material as witnessing, precisely that presentation in the forum again.

11 Shela Sheikh, 'Forensic Theater: Grupa Spomenik’s Pythagorean Lecture: Mathemes of Re-association', op. cit., p.187.

12 Susan Schuppli, 'Entering Evidence: Cross-Examining the Court Records of the ICT', Ibid, p.306. Within another register, the pendulum of mute (affectless) material/landscape and its interpretation which haunts Forensis, returns under the co-signs of media and noise. The video carrier's tragedy is recounted in Susan Schuppli's essay under the following terms: 'The material violations evidenced in the dense overlay of defects caused by the repeated copying and over-coding of the tape immediately alerts us to the material violations of the body proper that will soon emerge as the intended subject matter of the image.' Ibid, p. 309. The media image now is a body, subject to violation and attrition. This violence can however be simulated –- it does not (have to) bear witness to itself – distortion and noise, as Schuppli remarks, become tropes within films such as Michael Haneke's Funny Games. Yet: 'The massacre video cannot, of course, be compared to the narrative constructions of cinema given its status as documentary evidence of a crime.' Ibid, p. 309.

13 The title of a chapter [Ibid, pp. 109-124] which submits that "Before and after photographs are the embodiment of forensic time." A time operating also in reverse (the unbombing of Dresden proposed by Kurt Vonnegut, the re-revenant, the act of undying which is different for Derrida and is precisely not this autopsy, this forensis).

14 Living Death Camps Staro Sajmište / Omarska, former Yugoslavia. 1941-present [Ibid, pp. 191-233] describes in part how the Old Fairground (Staro Sajmište in former Yugoslavia), built in 1938 was converted (with its central panopticonic tower remaining unaltered) into a deathcamp, and is now the home to Roma communities and artists. It is the site also of a potential Holocaust memorial which would this displace these occupants.

15 A site where 'crimes against humanity were committed' becomes raw material for a monument which celebrates 'that same universal humanity.' (Ibid, p.217) The return of the same and the universal (public truth) within an always zombie and mobile architecture. Iron ore from the Omarska mines, site of the most notorious concentration camp of the Bosnian war, was used within a monument for the Olympics 2012 in London, reclaimed as the Omarska Memorial in Exile.

16 Cambodia's Killing Fields [Ibid, p. 116] and repeated genocides in climatically ravaged Pakistan [Ibid, p. 120].

17 Ibid, p. 616.

18 'Corexit - the carcinogenic chemical compound deployed as a dispersant - is manufactured under the monopoly of a US-based company named Nalco whose managerial board includes executives from powerful petroleum multinationals such as Exxon, and, not surprisingly, BP.' Ibid, p. 555.

19 As Timothy Morton writes in a work which defines the philosophy of dark ecology: The task is not to bury the dead but to join them, to be bitten by the undead and become them. See, Ecology Without Nature, Harvard University Press, 2009, p.201.

20 Füsun Türetken. 'Breathing Space: The Amalgamated Toxicity of Ground Zero', op. cit., p.254.

21 Godofredo Pereira. Geoforensics: Underground Violence in the Atacama Desert, Ibid, p.600.

22 Los hombres verdes, are the green men, workers of the Chuquicamata copper mine in Chile whose bodies are so contaminated with smelting by-products that they exude a 'gelatinous green substance'. Ibid, p.599. These bodies, contaminated in the underground (mines) are now in the process of being exhumed to provide evidence for the forum of local contamination both within the mine and the environs: 'the large-scale exhumation procedures of the hombres verdes are comparable to the exhuming of remains of disappeared detainees.' Ibid, p.601.

23 Tony Blair, quoted in Srdjan Jovanovic Weiss, 'Proportionality Complex: NATO's Bombing of Radio Television Serbia in 1999', ibid, p.235.

24 'By way of expropriating the intrinsic value of forms of life other-than-human, confining all possible manifestations of non-anthropological alterity to the category of (owned or unowned) property, the current legal order functions as a mechanism that conceals the most important ethical and cultural implications of environmental crimes.' Ibid, p.564.

25 The HKW, or Haus der Kulturen der Welt (House of World Cultures), exhibition site for Forensis and under the Anthropocene transitioning to a 'House of the World' can be viewed as one ignored forum of Forensis, as an already ruined, Cold War Einsturzende Neubauten (collapsing new building/s); referring to the collapse of its roof in 1980 and renewal/complete restoration allowing for a re-opening in 1987. The material story of the HKW expresses the relations of Forensis as a bright realism, with paranoia and conspiracy as contrastingly shady non-sites spawned across ad hoc forums by its very nature as a shadow. A never attempted de-crypting of the HKW would un-shadow a complex set of connections across the proper names such as Dulles, the CIA and I.G. Farben, a network of synthetics (against nature) and earth and body extractions which would point towards a schizo-zoic language of earth-no-bodies; an animist body which always lies.

26 Mirrored within S. Ayesha Hameed's Black Atlantis, which describes an undersea constellation of pearls, slaves and revenant bones. Ibid, pp.712-719.

27 Referencing the precise, architectural drawing of the slave ship Brookes made by the Plymouth abolitionists in 1788. Ibid p.41.

28 'Many [quotes] were never meant to be executed; they are there to test the market, to confuse or subvert competing algorithms...' Ibid, p.137.

29 Referring to the passage in Kurt Vonnegut's Slaughterhouse Five, which describes the bombing of Dresden reversed with respect to time (see below) cited in Forensis p.122: 'When the bombers got back to their base, the steel cylinders were taken from the racks and shipped back to the United States of America, where factories were operating day and night, dismantling the cylinders, separating the dangerous contents into minerals. […] The minerals were then shipped to specialists in remote areas. It was their business to put them into the ground ...'

30 The auto-icon is the preserved (after dissection) body or skeleton of moral philosopher Jeremy Bentham. This incomplete panotopto-auto-icon is displayed in University College London.

31 'because DTs must surely give access to dt's [note: the derivative with respect to time] of spectra beyond the known sun, music made purely of Antarctic loneliness and fright.' Thomas Pynchon, The Crying of Lot 49, p.89.

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com