Sex, Strikes and Andean Textiles

In her review of Ines Doujak and John Barker’s anthology, Loomshuttles, Warpaths, a materialist history and collaborative meditation on Andean textiles, Vivienne Richmond finds a cat’s cradle of power relations, craft and resistance that extends back centuries and up to the present

Loomshuttles, Warpaths: An Eccentric Archive 2010-2018, is a collaboration between artist Ines Doujak and writer and performer John Barker. It is part of an ongoing artistic research project which also includes a website and travelling exhibitions, and which aims to reveal, through textiles, the ‘highly complex and asymmetrical relationships between Europe and Latin America’.[1] The core of this Eccentric Archive is, then, a collection of 48 Andean textiles and textile-related objects, ancient and contemporary. They range from a wool and cotton Inca khipu (a knotted-string device for recording data), to an acrylic jacket bearing an embroidered image of Che Guevara, a manifestation of Bolivia’s 2009 revolutionary constitution. From a llama-bone wichuna (a pick tool used in weaving), to a cotton chuspa (coca bag) dating, in Western terms, from 400-700 CE. From a thousand-year-old mummy mask and wig, made of wood, human hair, alpaca, wool and cotton, to an early 20th century llama-hair costal (large food sack), as well as masks, helmets and caps, dolls, aprons, belts, hair ties, carrier cloths, carnival clothes, leggings, slings – and more. Collectively they demonstrate the intrinsic significance to Andean communities and cultures, across millennia and despite centuries of genocidal colonialism, of textiles, often of exquisite beauty and great technical skill.

The authors begin by setting out the volume’s conceptual framework and outlining the long and frequently ugly history of the global textile trade. This reveals how inextricably the trade is enmeshed with the history of empires, slavery and the growth of Western capitalism. Doujak and Barker also emphasise the central role of women in textile production and in resisting exploitation of textile workers, as well as the international division of labour, allotting to wealthy countries the well-paid work of design and development with manufacture carried out for low wages in poorer countries. They close this introductory essay with the bloody history of brilliant dyes and an example of the ways in which garments, adapting to changing circumstances, retain their political and cultural significance across time and place.

Images are all Ines Doujak, 2010-2017

In keeping with the Andean perception of textiles as animate objects, items from the collection were sent to over 50 individuals, including artists, designers, critics, curators, historians, philosophers, anthropologists and writers, prompting textual and/or visual ‘communications’ expressing the memories, sensations and emotions the pieces evoked in them.

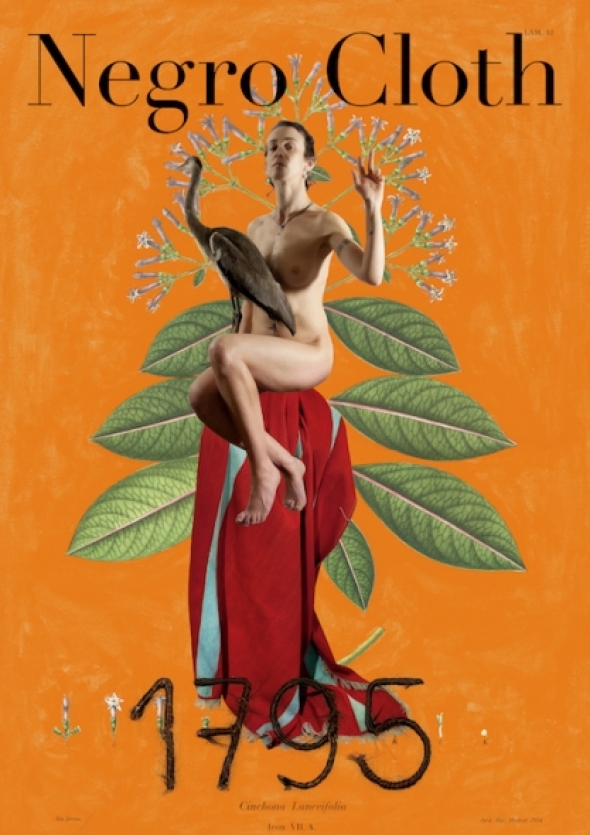

The main part of the book is separated into three sections which begin with a series of 16 photographic ‘posters’ made by Doujak, each a visual interpretation of one of the 48 textiles. The posters, designed to look like magazine covers, feature a central image, a ‘headline’ indicating the focal theme (for example, ‘Velvet’, ‘Indigo’, ‘Negro Cloth’, ‘Hateful Yellow’) and a ‘numerical date’ relating to an instance of class conflict in the history of textile production. Each poster is glued, along its top edge, onto a black background, and when lifted reveals short texts/details relating to the headline, date and associated communication. Following the posters are images and detailed descriptions of each item together with their ‘contextual, anecdotal, autobiographical, and technical’ ‘inventories’, extended discussions of the headline words and numerical date, which link the Andean textile to geographically and temporally wider histories of textile production, and the full communications, together with further archived images.

Loomshuttles, Warpaths dissolves the capitalist separation of producer and consumer, arguing that most consumers are also exploited producers. While centred around Andean cloth cultures, the authors deflect potential accusations of ‘research territoriality’, by placing the Andean objects and textile practices in a historical and contemporary worldwide context, making links between the oppression of textile workers in the past and their continuing oppression today. The result is a volume disturbingly replete with accounts of the use of slave labour in many branches of textile production, and in the persistent, international, undervaluing of women’s skills and labour to justify a gender pay gap. But equally it celebrates the numerous incidents of resistance, especially by women and even in the face of vicious offensives, such as the Korean workers daubed with human excrement by their male counterparts for seeking to elect female union leaders.

A summary of the entries for one of the 48 items in the collection can demonstrate this multi-faceted approach in practice. The poster with the headline ‘Indian Yellow’ depicts a brightly-coloured Andean woven cloth lying, as if dropped, on a tiled floor, and the date 1917. The inspiration for this poster was a wool and acrylic K’eperina/Manta or Carrier Cloth, acquired in La Paz in 2008. A black and white photograph shows that it bears visual similarities to the textile on the poster and its ‘inventory’ discusses Andean definitions of writing, how production of a textile imbues it with the power of speech, weaving as women’s work, the importance of colour, the human and protective attributes of sacred mountains, the related prayer and weaving practices of Bolivian Qaqachaka women and the fatal consequences of failing to complete a weaving before Carnival.

The discussion of ‘Indian Yellow’ reveals that it was an expensive dye made from the urine of cows fed only on mango leaves resulting in malnutrition and early death. It describes the dye’s popularity among 19th century European painters, its connection with ‘scientific’ racism and its ban by the British authorities who feared opposition to the maltreatment of cows might unite the people of India in rebellion.

Explanation of the date 1917 – the year Mahatma Gandhi first saw a spinning wheel – outlines the decline of India’s export trade in cotton cloth due to British production; the resultant symbolic, anti-colonialist, status of cloth in India and the formation of the Swadeshi movement to boycott British goods; Ghandi’s synthesis of Sanskrit law and Keynesian economic theory to bring Indian women back into the labour force; one woman’s creation of a spinning centre and organisation of weaving training to produce the iconic homespun khadi cloth; and Ghandi’s adoption of the dhoti as anti-colonialist dress.

Finally, in his communication with the K’eperina/Manta, Simon Sheikh addresses the question ‘What makes an object speak to me’ in a discussion ranging from pagan beliefs to modernism, drawing on Walter Benjamin, Roger Caillois and Kaja Silverman.

In the hands of Doujak and Barker, therefore, this single cloth is the lodestone which brings into unexpected, thoughtful and thought-provoking juxtaposition long-standing Andean cultural practices and beliefs, the history of dyes, opposition to British colonial rule in India and a meditation on the nature of language.

There is a growing body of scholarship on globalisation and the atrocities of the textile trade, but little as imaginative and protean as Loomshuttles, Warpaths: An Eccentric Archive 2010-2018. This ambitious, multi-layered, cross-disciplinary and sophisticated synthesis of image and text manages to be, at once, both a publication of visual and tactile beauty, a celebration of resistance to oppression and a disturbing record of the violent and exploitative politics of cloth and clothing, past and – outrageously – present. I was drawn to it as a historian of industrialisation, dress and poverty with a background in creative textile practice and a long-standing admiration of Andean textiles. It is, then, unsurprising that it contained so much of interest to me. But it is a book for everyone – with or without specialist knowledge – who wants to know about the indissolubly interconnected histories of textiles, trade and colonialism and about the true cost of the clothes on our backs.

Info

Ines Doujak, John Barker, Loomshuttles, Warpaths: An Eccentric Archive 2010-2018, Spector Books, Leipzig, 2018. 341 pp., 348 b/w illus., 48 col. pls.

49€. ISBN 9783959052184

Bio

Vivienne Richmond <vivienne.richmon AT gold.ac.uk> is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of History, Goldsmiths, University of London. Her work explores the social and cultural effects of industrialisation through the lens of non-elite dress and needlework. She is the author of Clothing the Poor in Nineteenth-Century England (CUP, 2013); the co-editor of Textile History (the journal of the Pasold Research Fund); and the co-editor of the forthcoming Bloomsbury Encyclopedia of World Textiles (Bloomsbury, 2023).

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com