Nervous Costume

Madame Tlank digresses from and back to Anne Boyer’s Garments Against Women, which is many things. A memoir written by someone without a history. A garment made for no-body. A reproduction fin in a great fleet of sharks

Down With Supreme Whateverness: On Anne Boyer's Garments Against Women

a catalogue of whales that is a catalogue

of whale bones inside a catalogue of garments

against women that could never be a novel itself.1

‘Who eats in a cage? Or with a caged mouth?’ This question leaps in white out of the first two black pages of Anne Boyer’s Garments Against Women. In it, the need to eat is shouted out loud. In it, the cage is seen and felt. And it’s made clear that in order ‘to survive survival’, to eat without a cage, it’s not enough to shift the cage (from mouth to just around the body, say): it needs to be ripped away. And fangs regrown.

Kafka’s Hungerkünstler refused the terms of survival that were laid out for him: he put himself deliberately into a cage, on public display, and refused to eat; the worst for him was to be force-fed once every 40 days; the sheer effort of lifting himself up to have food poured down his throat was already too much, so little interest did he have in survival. And why? Because, as the Hunger Artist confesses just before he perishes, ‘I could not find a food that tasted good to me.’2 Because he could see no point in surviving survival. It was all just so much pale grub.3

In Boyer’s writing, of course, the cage is no protection from present conditions, it is the present conditions, as embodied for example in garments and literature: ‘Literature, like garments, had so often been against so many of us, enforcing and sustaining the hostilities of a world with the unequal distribution of resources and the corresponding unequal distribution of suffering.’4 Survival itself requires assenting to those conditions, eating at least, if with a caged mouth. Refusing this survival means not-writing: not (in writing) (re)producing the conditions that would call such survival ‘life’. But accepting this survival also requires not-writing: paid and unpaid work, reproduction, etc. – things necessary for survival produce not-writing too. So that surviving survival, the will to want to live, to write, requires a world turned inside-out. And in Garments Against Women Boyer attempts to ‘imagine, foreshadow, call forth or negatively invoke a [writing] incommensurable with Things As They Are.’ (MH) It is a labour of love & rage.

But who would publish this book and who, also, would shop for it? And how could it be literature if it is not coyly against literature but sincerely against it, as it is also against ourselves? (p.48)

One version of Things As They Are:

If an animal is inescapably shocked once, then the second time that she is shocked she is dragged across the electrified grid to some non-shocking space, she will be happier than if she isn’t dragged across the electrified grid. The next time she is shocked, she will be happier because she will know there is a place that isn’t an electrified grid. […] She will go to the shocking condition – ‘science’ – and there in this condition she will flood with endogenous opioids, along with cortisol and other arousing inner substances. […] how is Capital not an infinite laboratory called ‘conditions’? And where is the edge of the electrified grid? (pp.1-2)

Boyer tests these conditions, putting their accidents on the page because others will have to go on doing so. She probes and tests, flinching, letting go and pushing on, up and downward. Made sick by ‘the supreme whateverness of upward moving depths’(p.53) – by the ‘unconstrained constraints’ (p.12), the bullshit choice between happiness or infirmity – she senses what lies between the pages of the closed book (‘another veracity that includes conspiracy, corners, shadows, slantwise, evasion, unsayingness, negation, and under-the-beds?’(p.36)) With her mind as the deadpan-logical mouse in this laboratory, Boyer tries to invert and hollow out the conditions, to lift the real from its carefully constructed frame.

Among components of the frame are:

1. The violence underlying everything, or ‘how money and bodies meet’ (p.9).

2. The need to make money (and to ‘Be MONEY like the universe!’)*. Transparent accounts and profitable desires.** The aspiring self itself5 and its cheaply bought mutations***.

*‘Be MONEY’ (p.69): in a hilarious half-page of the section called ‘Ma Vie en Bling: A Memoir’, Boyer corrects bits of high-serious canonical bluster (Char, Pasternak, Pessoa, Auden) by replacing the words ‘poetry’, ‘art’, ‘plural’, ‘inspiration’ with ‘MONEY’. In the line quoted above, Pessoa originally cried out: ‘Be plural […]!’ Auden, who thought he was talking about ‘inspiration’, is discovered by the same method to have said: ‘Such an act of judgement, distinguishing between Chance and Providence, deserves, surely, to be called MONEY’. Do try this at home.6

**‘Profitable desires’ (pp. 34/35): ‘It’s only necessary to make a transparent account if it’s necessary to have accounting, and it’s only necessary to have accounting in the service of a profitable outcome. To account in the service of profit is to assume the desirability of profit […] To steal is to behave as a natural extension and reinforcement of a desire that everyone knows is what’s real.’

***Cheaply bought mutations: ‘as if the smallest bit of drugstore blonde could alter a person’s person’ (p.6). ‘On how many of my hours are gone now because I have had to shop / On how I wish I could shop for hours instead’ (p.47) – for hours or for hours? ‘On whether it is better to want nothing or steal everything’ (p.47).

3. The body: the need to eat, the (impersonal) illness resulting from poverty*, infirmity**, our wants ‘made out of what is done to us’,7 the subsistence that goes on after power defangs us.

*‘Poverty’: ‘I was too sad to slug in the face. I was stoned and inconsolable. I was a weary rocket engineer looking at the twisted remains of a bad shot-defined astronautics. I wanted to be addendum free’. (p.63)

**‘Infirmity’: ‘I am not a fan of infirmity, though it does supply the opportunity for some relief.’ (p.13)

Fangs – we need them!

Literary convention established to make knowing what we needed to impossible8

By continuing to write after having failed to refuse to write, by writing, Boyer wills literature to stop (re)producing these conditions, stop functioning within or creating a frame (as do garments, encasing bodies which might flail their arms uncontrollably) that disguises the violence on which it is built.9

Just one example of Boyer’s expert frame-shifting: ‘The classic example of a positive contrast is produced by hitting yourself on the head with a hammer. The pain produced is part of the ordered dimension and so the more of it the more you get adapted to. Thus, when you stop you “feel great”.’ (p.14). And, later in the book: ‘Things were great after that. They really got better. I wrote words in great paragraphs. There were great acorns. I had a great toothache. There was the great noise of the great leaving geese.’ (p.70).

An impulse to action sings of a semblance [...] The measure [...] congealed [...] things keep no resemblance [...] Like night is like us [...] mentors [...] hardly enter [...] our centers do not [...] our value estranges.

– LZ

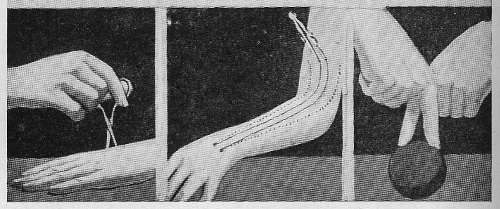

Writing (or its product, literature) needs to be wrenched from its place in the given conditions (as literature against women, just as sewing must know its material, re-grounding the garment as use value (as opposed to a form wrenched out of and imposed on women). And: how to make a seam?

Poetry and clothes are made of the same stuff: the history contained in the fabric or language; the hours of labour embodied in that material and its transformation into garment or poetry. The history of those who wrote and sewed the stuff: the present tense of those who read and wore it, those who heard and saw them. Dead labour walking whenever you wear that dress. Each time you recite that poem to protect you in the violent rain you bring forth the zombies.

Writing needs to expose its threads, garments need to bring back their dead bodies.

I kept checking the social fabric for the hole I'd burned. (p.80)

Uprooting the history of the Now entails ‘resistance to the present and its versions of the past’ (MH). Elsewhere, in a sequence of ‘Questions for Poets’ published by Mute, Boyer asks, ‘What is the direct trial that is today?10 This text is not only a catalogue of questions, it is also a bibliography of the writing that gave rise to the questions, and as such a history of questions.11 The first reference in the first of many footnotes rings out: ‘The direct trial of him who would be the greatest poet is today.’(WW).

Poetry is history writing, a history of and in the now, ‘everything in the everything’ (p.20). And then, after many questions Brecht could not have asked better, comes this: ‘Is it all of that and how it is against ourselves? Is it to burst, to ruin / to disrupt our continuity with history? Is it to never have history again? Is it the enclosing of tears?’

A poem is (or can be) a split second, a century, re-written as condensed NOW; a quake in continuity. Can it work into a present-tense nervous system12 the ‘actual heaving everything of the human everyone’ (p.51)?

I shall be a charming, utterly spherical zero.

– RW

Maybe the little girl’s 0s (as described by Rousseau in Emile, the only thing this girl would write and write and write), shaped backward, using a needle, constitute writing towards surviving survival.

Boyer lists some things the girl might have enclosed into her 0s, ‘a planet, a ring, a word, a query, a grammar’(p.84). Or maybe the 0 was just a NO:13 endless repetition of a symbol devoid of meaning without a context. Refusing to signify. And drawn backward at that. With a needle (not making garments), not a pen (not writing language). The possible worlds contained in the negation. Rousseau claims the girl stopped writing because she saw herself writing and hated what she looked like (but maybe she just thought that her 0s were too beautiful for this world?). ‘Afterwards’, he writes, ‘she was only persuaded to write again in order to mark what was hers.’14 The refusal failed, the girl adapts but not quite. She never wrote again, only marked what was hers. Her territory. Objects delineate her world. But Boyer sees it otherwise: the girl stops because she is done with her work: ‘The little girl in Rousseau needed only to write down her own name now: she had written, already, her revolutionary letters in the code of 0’s.’(p.85) Revolutionary letters, decoded in Rousseau’s head: an impulse stalled.15 In Boyer’s writing: an impulse continued – – – – –

Negative alphabets.

I am nothing and I should be everything.

– KM

Mme Tlank: Sie wissen nicht, mit wem Sie reden

Info

Anne Boyer, Garments Against Women, Boise, Idaho: Ahsahta Press, 2015.

Notes

Non-AB citations in order of appearance:

MH: Clinical Wasteman

LZ: REDACTED in deference to a litigious filial fiddler. (See, http://www.z-site.net/copyright-notice-by-pz/)

WW: Walt Whitman

RW: Robert Walser

KM: Karl Marx

WCW: William Carlos Williams

ED: Emily Dickinson

WS: Wallace Stevens

MM: Marianne Moore

American canon excerpting by Clinical Wasteman

Footnotes

1 Soiler alert! Certain of Anne Boyer’s words and phrases are inverted or displaced in what follows, in a sort of tribute to her own redirecting of other writers. Page numbers otherwise unattributed are from Garments Against Women, longer passages quoted from Boyer's other works are indicated. Quotations from other authors cited are initialed in the main text, decrypted at the end. This quotation p.86.

I urge all readers who haven’t done so already to read all of Anne Boyer’s writing, a lot of which is available on her blog at http://anneboyer.tumblr.com/ There are also links to other reviews of the book to be found there, which are all very beautiful and intimidated me a lot. Read those, too!

2 Translation from https://records.viu.ca/~Johnstoi/kafka/hungerartist.htm

3 There are of course many other readings of this story. However, hardly anything has been written on the ‘work’ and ‘pay’ aspects of it. This may be forthcoming.

4 See Anne Boyer, Author Statement, Ahsahta Press, 2015, https://ahsahtapress.org/product/boyer-garments/

5 ‘ASPIRATION (1.) [...] a strictly personal kind of anxious conformism. The aspirational individual [...] expects to compete and win against the rest of her class on a “level playing field” (i.e. everyone doing the same thing), beating her opponents fairly by embracing more eagerly, energetically and obediently whatever rules of the game are transmitted from above.’ See Wealth of Negations, Terms and Conditions: Welfare Edition, http://www.wealthofnegations.org/

6 The American poetry canon seemed the obvious place to start, if only because the corresponding English one is not worth the embossed vellum it’s bound in.

This is just to say

I have eaten

the MONEY

that was in

the icebox

and which

you were probably

saving

for breakfast

Forgive me

it was delicious,

so sweet

and so cold

[WCW]

The MONEY passed – identified –

and carried Me away –

[ED]

“Things as they are

Are changed upon the MONEY guitar.”

[WS]

I, too, dislike it

[MM]

7 See Anne Boyer, http://anneboyer.tumblr.com/

8 See Anne Boyer, Author Statement, Ahsahta Press, 2015, https://ahsahtapress.org/product/boyer-garments/

9 On the violence built into garments, see the extensive research by Ines Doujak with John Barker for the amazing project ‘Loomshuttles / Warpaths’: http://www.inesdoujak.net/lswp/

10 See Anne Boyer, ‘Questions for Poets’, Mute, 2014, http://www.metamute.org/editorial/articles/questions-poets

11 ‘Every poem until the revolution comes / is only a list of questions / so mourn for the poet / who must mourn in their verse, their verse.’ From another poem by Anne Boyer (title and publication unspecified), which she quotes in an enlightening interview with Amy King which also discusses the title of the book in depth. Straight after the quoted passage, Boyer adds: ‘And by “revolution” I mean I don’t know.’ http://www.poetryfoundation.org/harriet/2015/08/literature-is-against-us-in-conversation-with-anne-boyer/

12 Or in keeping with the more instructive German usage: ‘nervous costume’, as in ‘custom’, or ‘garments’.

13 ‘Her first word was NEIN!’ Double Negative, Glass Wolf Hides Mechanical Hare, deleted CDR, 2006.

14 ‘Only stuff is private.’ See Hari Kunzru, ‘Fill Your Life With Win!’, Mute, 2009, http://www.metamute.org/editorial/articles/fill-your-life-win

15 As for Rousseau: bon pour brûler!

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com