The Garden of Earthly Delights

Buy on Amazon UK £9.99 and other regions, Super Saving free shipping.

As the financial crisis fastens its grip ever tighter around the means of human and natural survival, the age of the algorithm has hit full stride. This phase-shift has been a long time coming of course, and was undoubtedly as much a cause of the crisis as its effect, with self-propelling algorithmic power replacing human labour and judgement and creating event fields far below the threshold of human perception and responsiveness.

Establishing a temporary experimental research station within spitting distance of East London's Olympic Park, The Crystal World proposed to decrystallise digital dystopia and recrystallise unlikely new contingent cultures. Matthew Fuller wades through the muck

For several decades the most formally inventive exhibition in London has been the Minerals Gallery in the Natural History Museum. With a meteorite at its apex making a suitably off-world fulcrum, the tens of oak display cases ranked across the long light hall present hundreds of prime specimens of minerals in all their shockingly varied capacities of growth.

Whereas most of the other galleries in the museum are punitively but sparely interactive, or set out like walkthrough text books made with surfaces ready to be hosed down after each group of snot and grime exuding schoolchildren have been rammed through at the speed of their presumed attention spans, the minerals gallery offers you nothing except the capacity to encounter the utterly fecund world of basic matter. Each specimen is chosen to represent the idiotypical colouration, growth patterns and texture of certain chemicals and their mixes, and the world of minerals is, we learn, voluptuously and finely creative, and it becomes abundantly obvious, with the expressive capacities of elements as they mix under different conditions, that the universe is amazing. It is also rather disconcertingly neat.

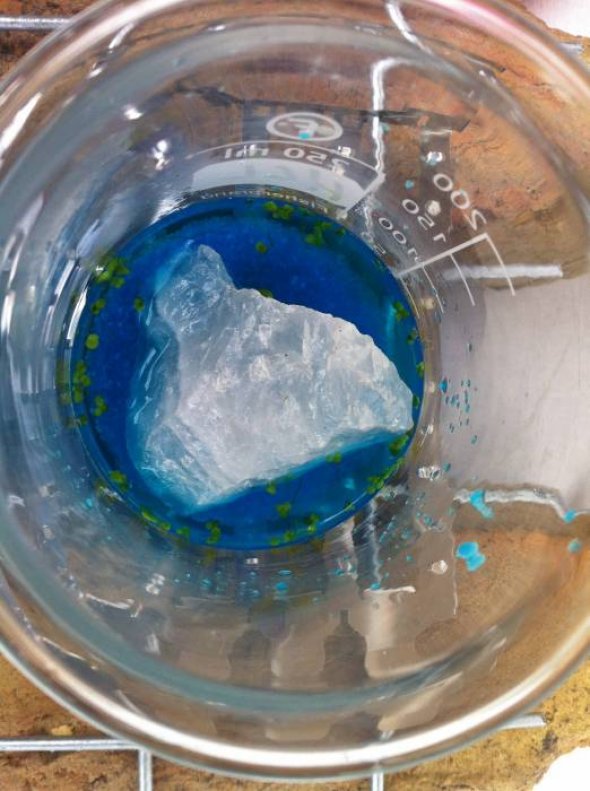

All images from the Crystal World exhibition, The White Building, London, 2012

Something of the universe’s unruliness, its filthy playful accident is rather more manifest in The Crystal World exhibition by Martin Howse, Ryan Jordan and Jonathan Kemp recently on at the Space White Building. Titled after J.G. Ballard’s novel of encroaching strangeness, here the earth is transformed into a gigantic grunge chemistry set. The chemist Dmitri Mendeleev famously found the final proportions of the periodic table in a dream after much intense work of experiment and calculation, and something similar is going on here. The exhibition proposes intense links between matter, abstraction and the fantastic, the combination of computation, accident and intuition. In the periodic table, matter proceeds along two axes with a gradually changing set of qualities arranged by atomic weight and atomic number, (a quality added later following work by Henry Moseley) changing in terms of conductivity, malleability, the ability to react with or combine with other materials and so on. The whole table, with each change arising from the accretion of one electron at a time, formulates, at a certain scale of analysis, all of the abundant expressivity of matter arising from what Mendeleev called the invisible world of chemical atoms.

The Crystal World project is an attempt to break that expressivity free from the constraints imposed on it by what can be called the norm-forms, normative formations, that run through contemporary culture. Set across the canal from and partly funded by the ‘legacy’ of the Olympic Park one of the great excrescences of such, The White Building seems a prime location to do so, but the particular focus of the show is on the way in which the fruits of the periodic table are yielded to us in computing and electronics. Computing is a particularly interesting place to track such things because it can be both highly abstract and very concrete at multiple scales, from those of logic, to interface, to hardware and its interpolation with aesthetics and the social. Equally, due to the high degree of abstraction involved in computing, coupled with its fundamental qualities of generality – that it is capable of making possible, simulating and improving upon numerous kinds of machine, computing is a site where norm-forms are particularly potent and also highly contestable. What this exhibition proposes is that we go back to some of the fundamentals of computing, its ‘primitives’ in a sense and to some basic chemistry, to see how they intermesh, but instead of routing them through the standard objects through which it is normally accessed, laptops, phones, synthesisers, software, and so on, we do so by working with what looks suspiciously like Hackney, or the debris of the glorious information age.

In the centre of the room, water from the neighbouring Grand Union Canal cycles through a tangled network of clear plastic tubes. Tinged with a spot of sulphuric acid it is pumped upwards to spatter down through a clump of assorted stones suspended from the ceiling on a steel grid and from there over a heap of broken motherboards on another grid, this one of a finer gauge and visibly sagging and corroding. From there it cascades into two large tubs made from sliced-open plastic water tanks set off from the floor on shipping pallets. Over the period of the show the canal water has yielded a good crop of white slime clinging to the wires and the tubes, undulating in trails as the drops run in.

From those two tanks, the enriched liquid is fed to six smaller ones fixed out of split polythene jerry cans sat in the upper quarter-part of one of the larger water tanks. In each of these a different set of ingredients stirs: heat sinks broken out of computing boxes, with a chunk of iron pyrites on top under a slow drizzle of acidulated canal; a tray of wood shavings thick with clumps of mycelium yielding a particularly toothsome ivory toned fungus; two trays of acid with assorted copper parts slowly oozing into luridly green, yellow or sky-blue tinctures and scums; two trays of silver nitrate, one with a black matt of congealed metal pinched by electrodes, another, some ancient gravy pierced by crocodile clipped pencils functioning as electrodes. Leachate and contamination from one bowl to another, stirrings of electrons and molecules in the wrong places, this is the nightmare that the European Electronic Waste Directive was supposed to protect us against. Whilst I am there, a pipe flops out of its fixing and dumps a pint or so of best onto the floor which, judging from the grey traces of splashings, has seen a certain amount of disgorgement amidst the general miasma.

A miasma of course is a means of describing a state of matter that is disturbing, yet has not yet been analytically described, one that may be morally compromising. There’s a romantic proposition here: matter is active, making its own state, analysis is superfluous by comparison with experiment with prurient oxides, chemical curds, and signals processing something. All of the separate parts of this system have their own microclimate, their own special set of currents, purities, and congealments, but they all take part in a general economy of oozings based on drainage, cycling, dissolution and the light frazzle of electrically active acids and devices and substances sensitive to them.

To one corner of the larger mass sits a tiny delicate clutter. Rudimentarily modelled on the axon hillock structure that transfers and triggers electrical activity in the nervous system, thin angular copper wires connect in groups of three to small chunks of chalcopyrites. The wires in turn are connected to a further set of tubes containing some fluid and a build-up of sodium crystals. Wired, these are plugged into an amp, feeding into a clutch of stray-looking speakers, magnets down, on the floor. Over the course of the month, this structure has gone from emitting a stream of clicks and crackles over a baseline of white noise, turning to occasional bleeps and pulsings, to silence. Something came loose, implying no particular dividing line between the broken and the rest.

Around the four corners of the room are various tables used for a five day open lab run as part of the show.1 They are arrayed with the debris of chemistry labs and kitchens, fish bowls with electrodes and crystalline build up, silts and salts; books of minerology, alchemy and history next to a row of impressively molding pots of yogurt made of milk taken from cows. On another bench, fragments of computers are laid out with various crystalline growths upon them. Hard drives soused in acid covered in white fuzz. Pickle jars full of Rochelle Salt crystals; clumps of quartz; fans wired to switches wired to speakers wired to magnets; a salad of circuit board fragments liberally dosed with short strips of copper wire to encourage impromptu networking, a small bone covered with glistening crystals laid out on a dark tray of untreated hardwood; powders, rusts, limonite, dried up daises, numerous nameless residues biding their time. From one of the four pillars, a pair of cassettes dangle, disgorging their tape, a yield of tiny white crystals on its surface.

A Ziploc bag of sulphur remains on one of the tables from a sizeable batch that was burned with a high voltage connection over on the floor. A clutter of vaguely scorched sticks and bricks remain from its handling. By the time you have examined all this material, the background buzz has gnawed its way into the forefront of your consciousness. The grey slag of the burned sulphur lies like a mini-Pompeii on the concrete.

On another bench, a microwave oven sits atop another, jammed full of ceramic wool. Giving it this extra element turns the oven into a furnace capable of reaching over a thousand degrees centigrade, used to refine iron from haematite at over 1200°C. One of the bricks on the bench had both crushed haematite and melted iron still in its recesses. Many of the chemicals used in this show have been burned, siphoned, distilled and rescued from their accrual in circuit boards and devices. The remains of computing becomes chemical, a source for reconstitution. A wiki accompanying The Crystal World project gives extensive documentation on the techniques used to suck the gold out of circuits or drain the metals from ores. A library of materials used as sources can be downloaded as a reader.2 A general principle of the work here being a gathering and proliferation of unexpected connections, through bodies of knowledge, through disjoint components and amongst elements, compounds and what they congeal.

Along the last wall, on top of some thick polythene sheet, lies the Earth Computer. Two thick lengths of copper lead into a tray set into a bed of mud, the tray containing lumps of scavenged copper and zinc in a solution of silver nitrate. What comes in and what goes out of this computer depends upon the stirrings of its components and what the earth might happen to send through it – lightning perhaps: the contraption is due to be buried nearby after the closure of the show. Like all of the constructions here each concentration of work is not strictly delimited for contemplation. Residues of its making, sheets of notes, buckets, bottles, scraps of stained paper, cracked panes of glass, highly skirtable puddles, all lie around. Some large sheets of paper are pinned to the wall incidentally bearing traces of spillage, a crop of small mustard coloured crystals surrounded by an aura of blue leavings.

To one side, two cracked cases of once desirably sleek and pokey high-end Macs support the polythene-wrapped carcass of another computer. Filled with motherboards, wood shaving and acids and prepared with spores, it forms the ground for another crop of pale fungus. The ground beneath is white with the puddles of crystals drained out from the little patch of paradise that it forms. Lying on the floor next to it, a PC case full of broken circuit boards funnelled full of haematite and aluminium powder, lit for a while and then promptly doused, sits scorched and faintly aromatic. Five lightly carbonised brick parts lie around as some kind of witness to a process.

The other top cut from one of the larger tanks sits on the floor full of fluid, its bowing sides held up by a haulier’s strap. At its centre is a section of a clay pipe a forearm’s length across. Inside is a clump of more sandy earth and within this a chunk of silicon and three small clay flowerpots holding various solutions, with two electrodes trailing in. The silicon was melted from powder into tiny 'chips', achieved by getting the microwave to work at over 1410°C. Silicon powder itself was made in the lab with ordinary sand and magnesium with heat and hydrochloric acid added – a move towards a dirty silicon chip.

The surface of the liquid is a dull brown that, gathered into an archipelago of salts, has grown into a kind of skin, as puckered and glistening as something in aspic. There is rust around one of the electrodes. A car battery opened, a Leiden jar devolved into a near Neolithic technology growing a new culture of scums and delicate membranes into pond full of bitter consommé, a pit from a leather works that in turn grows its own epidermis. The landscape of The Crystal World, one of spillage, broken components, leachate and electrical bleeds suffused with a tang of corrosion sits across from the imagined universe of trickle-down and high performance flesh, the two cosmologies insulated by the Grand Union. The expressive variety of the table mapped by Mendeleev inevitably outpaces the power of accidental computing – as understood in terms of mere input and output – simply on the basis of sheer likelihood, its combinatorial capacity magnificently abundant here. But, as electrons circulate amongst and between the compounds, this exhibition also shows how close they are and how much their inter-relations proliferate.

Matthew Fuller’s <m.fuller AT gold.ac.uk> recent books are Elephant & Castle, Autonomedia 2012 and, with Andrew Goffey, Evil Media, MIT Press, 2012, http://www.spc.org/fuller/

Info

The Crystal World Exhibition by Martin Howse, Ryan Jordan and Jonathan Kemp took place at The White Building 28 August to 1 September 2012. The Crystal World Open Workshop took place at the White Building 17 July to 21 July 2012.

Footnotes

1 For information on participants see: http://crystal.xxn.org.uk/wiki/doku.php?id=the_cry...

2 The Crystal World wiki is at http://crystal.xxn.org.uk/wiki/doku.php

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com