Orgy of the Non/Self

Yayoi Kusama’s current Tate Modern retrospective provokes Josephine Berry Slater to join the dots of the artist’s agonising and ecstatic constellation of obliteration and multiplication

Yayoi Kusama can paint, I mean really paint. Her early works, displayed in the Tate Modern retrospective, would take you by surprise if you had her pegged as that dotty lady, the one whose only idea is to cover every available surface with polka dots. But the logic of the dots seems to have developed with surprising continuity from these early paintings, their rhythms and patterns, which explore accumulation as the constitutive force of the cosmos. Like Daniel Buren and his stripes, there is a tension in her later dotty work between a signature device which risks becoming a deadening calling card of identity, and the use of an accumulative gesture which generates fields, states and environments beyond the provenance of their creator. With Kusama’s work, the later installations as much as the early paintings, repetitive gestures comprise a code which builds out from identity and even art, to produce patterns which throb with a cosmic pulse of creation. Her painstakingly rendered dots, which should at all costs be distinguished from those sweated out in Damian Hirst’s accumulation factory, also presently on display at Tate Modern, share with the early paintings the power to reflect and induce the joyful agony of self-obliteration. ‘Self-obliteration’, a phrase she developed in the ’60s during her Body Festival phase, is the necessary stake of her creativity, but one that always menacingly threatens a collapse into self-destruction.

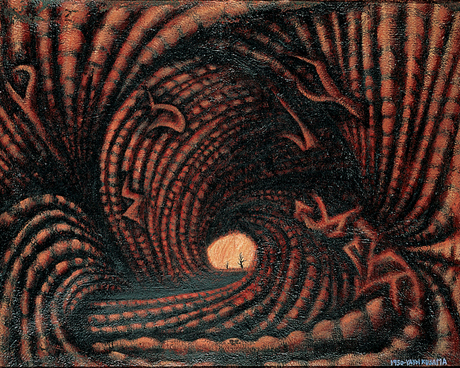

Image: Yayoi Kusama, Accumulation of the Corpses (Prisoner Surrounded by the Curtain of Depersonalization), 1950

Kusama’s parents ran a plant nursery business in Matsumoto City, Japan, and her early paintings bear many traces of a child’s micro-perception of flowers, plants, seeds and insects. From the materials she used – household paint mixed with sand and seeds, a consequence of post-war austerity – to the butterfly-winged delicacy of her paint brush as she specks and flecks the hypnotic biomorphic forms that flowed irrepressibly from her hand, her art is propelled by a vitalism, a feeling for generative life, that would carry her away were it not combined with a steadying intellect. This intellect can be seen at work in the sparse, gestural brevity of a gouache work like Flower Bud No.6 (1952) as much as the decisiveness to carry off more epic and sustained pieces like Accumulation of the Corpses (Prisoner Surrounded by the Curtain of Depersonalization), (1950). This latter work, painted some five years after the atomic attacks on Japan, depicts a tunnelled folding of intestinal cords, which sometimes burst open into vaginal lesions, drawing the eye down to a central aperture, populated by two tiny bare trees. It is a surrealistic cry of pain somehow lifted from terminal angst by the bold sensuality of its fleshiness, its sexuality.

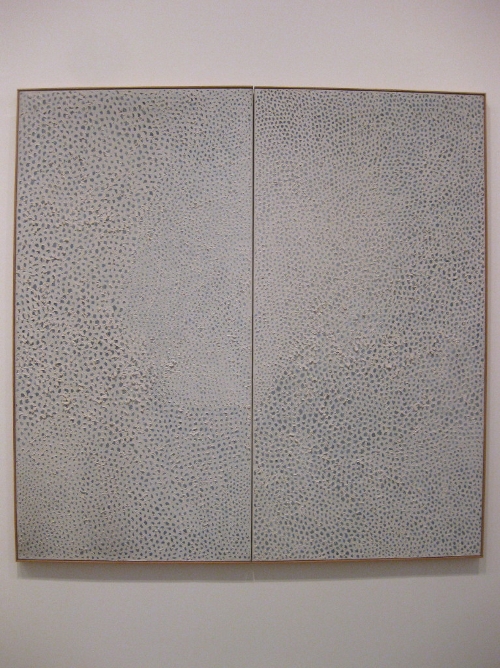

The control, or rather, precision of these early paintings reaches a different order of magnitude in her Infinity Net paintings of the late ’50s, undertaken as she struggled to make it as a painter on the mean streets of New York City. These entail the repetition, ad nauseum, of a ‘simple act’, the rendering of a tiny loop or ‘O’ of white oil paint, concatenated into giant nets which, on closer examination, appear to have been built up in concentric circular patches. These meshes were rendered over washes of pacific blue or grey hues, across canvases of up to 14 feet. From her diary, also titled Infinity Net, which I briefly perused in the gallery shop, it seems like the state in which she painted these works was often more hallucinatory than meditative. Her trance-like state was intensified by the hunger and cold she suffered during a spell of abject poverty on arrival in New York from Seattle, her point of entry into the country. The limited money she’d been allowed to bring through customs, boosted as it was by the additional cash stuffed into her shoes and sewed into her clothes as well as a stack of kimonos, dwindled to nothing in the devouring city. Sleeping on a door scavenged from the street, shivering under a single blanket through the New York winter and with the heating turned off at 6pm every evening in the warehouse building where she live/worked, she drove herself from dawn to dusk, pausing only to eat a meagre meal. Painting the nets became a way to withstand this bodily ordeal. It is important to register the depth of her isolation and fragility in this stage of her life, and how it creates another ‘ground’ over which the net was thrown.

Image: Yayoi Kusama, Pacific Ocean, 1960

Later she said, ‘This was my “epic”, summing up all I was. And the spell of the dots and the mesh enfolded me in a magical curtain of mysterious, invisible powers.’ The libidinal machine of the net paintings had a dual magic: to create a subjectless and centreless field, a field infinite enough to blot out and dematerialise the overbearing, canyon-like streets of Manhattan, the gnawing hunger, the pain of her desires, and on the other hand, to launch a guerilla attack on the machismo of the New York school painters. These paintings proved to be her meal ticket, landing her two shows first at the small artists’ co-operative gallery, Brata, on Tenth St. in 1961, and then a solo show at the prestigious Stephen Radich Gallery. Against the heroics of American abstraction epitomised by Jackson Pollock – whose drip paintings attempted to thwart representation but nevertheless always courted it, as the splats and drips powerfully evoked the bodily and biographical forces which produced them – Kusama’s work is ‘exhaustive’, as Mignon Nixon puts it. It entails a painterly drudgery that empties out identity and signification. There is an invocation of female reproductive labour that can be glimpsed in this mastery of the ‘mundane’ (Kusama’s word), the quiet doing and re-doing of a task that self-effaces, quells the appetites, produces others, wears you out. And yet, these paintings are rendered on massive canvases and in oil, which may have seemed obligatory for anyone wanting to be taken seriously on the gallery circuit at this time; both were new departures for the painter who’d previously worked on a smallish scale, on paper and with inks, gouache or homemade concoctions. Along with many women artists of her generation, she elevates the mundanity of feminine handiwork, of craft, but it is hard to call to mind many who challenged the male avant-garde so forthrightly in its own, epic terms. How, though, should we consider this contradiction between Kusama’s desire for recognition, even stardom, and her wish to self-obliterate?

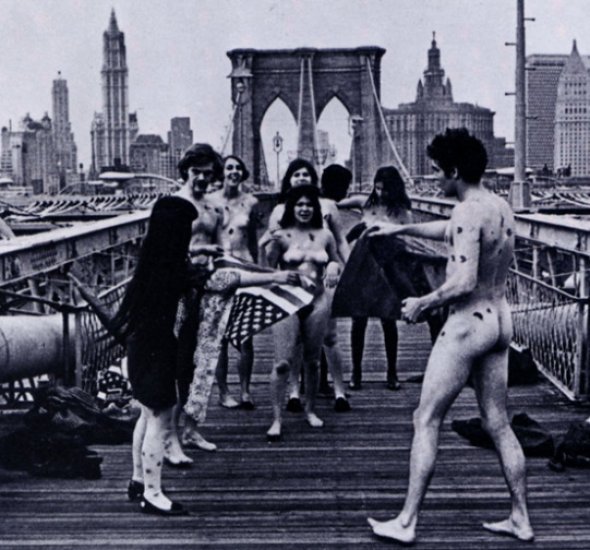

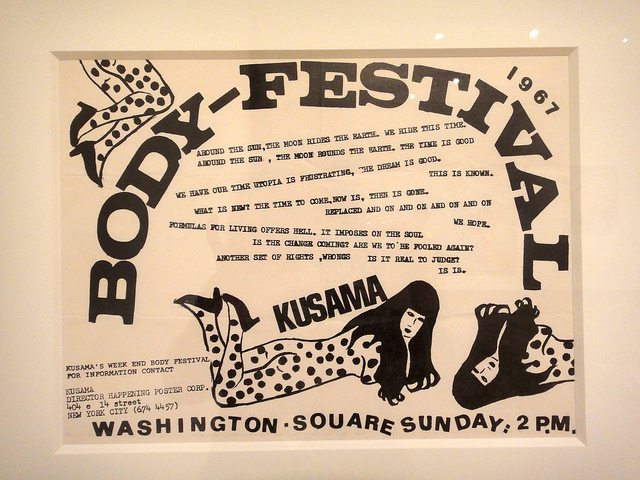

Image: Yayoi Kusama, Body-Festival Poster, 1967

One answer could be that fame is itself a form of self-obliteration, since publicity is a kind of repetition compulsion spewing out reproductions of a name and image, a name, image and slogan, a name, image and slogan that equals a ‘style’ which, in a sense, is ownerless or at least masterless. The accumulation of publicity produces a power which confronts a self steadily overwhelmed by its own projected image. Of course it’s unlikely that Kusama would have deliberately courted such a piranha attack upon herself – she talks, instead, of her blood running hot with the desire to revolutionise art – but there is a growing sense, towards the end of the ’60s, that her own self-publicity machine had run out of control. Jumping on the flower power, free love bandwagon, she began staging Kusama Body-Festivals, Anatomic Explosion happenings, Kusama’s Self-Obliteration events, and even launched a fashion label. What is striking about all this is her utter seriousness in the midst of what, from the looks of local headlines, was widely perceived, and enjoyed as no holds barred bohemian hedonism or free love with an Oriental twist. The obligatory self-expression of the ’60s counter-culture, apparently at one with Kusama’s naked orgies where everyone painted each other with dots and danced to the groovy psychedelics, is somehow sobered by the intensity of her injunction to self-obliterate. Both parties seemed to be opportunistically interested in what the other had to offer: the exhibitionists could reveal all and express their natural proclivities at her events, while Kusama dematerialised them into a field of dots. In a film titled Kusama’s Self-Obliteration, she applies painted dots to a male participant’s genitalia with an expert hand and oblivious concentration. The exhibition contains many of Kusama’s flyers from this period, giving a sense of both how hard she drove herself and how serious she was about connecting to the counter-culture. One of her first Self-Obliteration events was at Woodstock in 1967, and the promotional text itself exudes something of the discomfort of this mash-up of pop and avant-gardism:

Become one with eternity. Obliterate your personality. Become part of your environment. Forget yourself. Self-destruction is the only way out! On your trip take along one of our live bikini models.

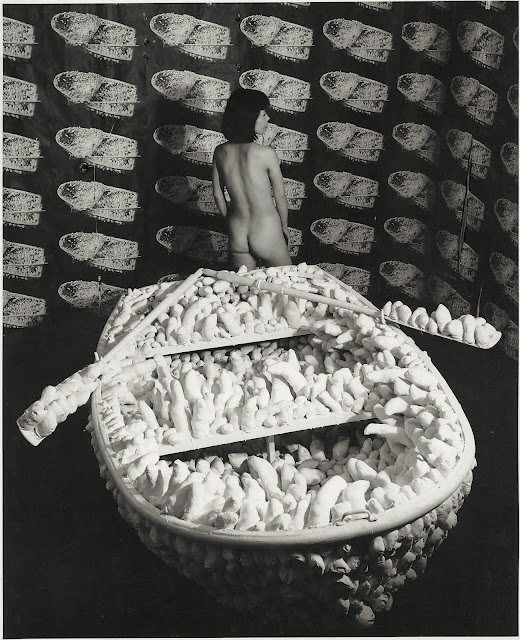

It’s easy to discern echoes of pop irony in Kusama’s adoption of marketing spiel and, as it turns out, Kusama was both an anticipator and glancing collaborator in the movement. Her 1963 installation Aggregation: One Thousand Boats Show, pre-empted Andy Warhol’s use of wallpaper by several years as a means of environmentalising two dimensional images and estranging them through repetition. This work, which preceded the self-obliteration festivals, came in the midst of her accumulation sculpture period, which are reminiscent of the slapdash, prosaic plaster objects in Claes Oldenburg’s shop. Kusama relentlessly covered household objects, shoes and clothing in monochrome protuberances, often referred to by critics as ‘phalli’, though they are equally reminiscent of the tentacles of sea anemones, pebbles on a beach or animal droppings, as my kids pointed out. The boat installation, while sharing the use of industrial repetition with pop, belongs most of all to the surrealist phylum. A rowing boat, with oars resting along its sides, is covered in biomorphic tentacles and spray-gunned white. It sits, spotlit, in a room entirely covered with black wallpaper printed over with a photographic image of the boat that forms its focus. This romantic escape vessel, which makes you think of the Lady of Shalott’s doomed pursuit of Lancelot, has passed from the epic’s production of solitude into the desiring-production of the unconscious as it proliferates a-signifying flows. The boat has been perverted, and this perversion is also cinematic; the wallpaper’s photographic repetition of the image also alludes to the cinema’s production of movement through the repetition of frames. But the boat is grounded for now, and its absent steersman is no matinee idol running on the tracks of narrative, but the accumulative force of the libido whose byproducts silt up the world, clogging up the cogs of all our projection machines until they shudder to a stop.

Image: Kusama posing in Aggregation: One Thousand Boats Show 1963. Installation view, Gertrude Stein Gallery, New York. © Yayoi Kusama and © Yayoi Kusama Studios Inc

A work which might seem to reduce the dramatisation of her immigrant and female vulnerability to the level of farce is Walking Piece, 1966; a series of photographic slides taken by Eiko Hosoe projected onto a wall which document her walking around some of the industrial and poor neighbourhoods of New York in pink kimono, gold slippers, plaited hair and an umbrella covered in flowers. We see Kusama pose for photos amidst what can only be described as the toxic brutality of New York, her flower-like delicacy offsetting the filth of the gum stained pavements, the vulgarity of signage (‘Banquet Meat Pies 2.35’), the ambient pollution (in several slides she dabs her eyes with her sleeve, as if cleaning out grit), and the lie of the American dream (in one slide she strides away from the Manhattan skyline, the Empire State appearing as a distant fantasy; in another, a poor white woman sits on chair in the street, watching the artist go by, in a further one she inspects a homeless man asleep under a tree). If anything, these images seem to dramatise the bankruptcy of what might be inadequately called industrial capitalism or the American way of life; her delicacy isn’t fey, for her expression is wise, her gestures highly conscious. She seems to represent an alien consciousness making observations which will be ported back to a more evolved life form, or a witness of all these sorrows. Both her choice of locations as well as the insertion of her kimono’d form bring forth the ‘masculine’ side of the city – its smokestacks, main arteries, silos, its crushing labour – not as a way of dramatising her vulnerability, I think, but in order to bring its crushing, productive logic to the fore.

This is one of Kusama’s few detours into representation, even documentary, and it certainly strikes a different note to the vitalist positivity of much of her other work. But, if we consider some of the early Holocaust inflected images and their titles (Corpses, Accumulation of the Corpses, etc.), it is possible to see how her exodus from representation as much as identity is consistently connected to a civilisational horror, a recognition of the abyss of humanity’s attempts to master nature and substitute it with something better. Or, as with the resemblance her paintings evoke between flowers and planets, she likewise registers the multiple scales of brutality, finding it at the heart of innocuous domestic objects as much as in industry, science and, indeed, art. The accumulation sculptures of the early ’60s erupt the apparent homeliness of domesticity, revealing a lurking perversity – sofas and armchairs are ready to mindlessly violate their sitters and enjoyment itself is understood as something structural, endemic to muted and naturalised power relations. In The Man, 1963, she covers a canvas in phallic feelers, and suspends a kettle from the longest one, seemingly urging some handmaiden to put the kettle on. This connection of the canvas to an endemic sexism brings to mind the concluding lines of beat poet Diane di Prima’s The Quarrel from 1961:

Hey hon Mark yelled at me from the living room.

It says here Picasso produces fourteen hours a day.

Kusama is an unlikely feminist, as well an unlikely negator of capitalism. She seems, in many ways, too complicit with the system, both the art world and the seduction industry. The photo on the cover of the Tate catalogue is a perfect example of the problem. She lies on her back in a field of stuffed and spotted biomorphs, her eyes blackened with ’60s eye makeup, hair spread out and her dress pushed up past her knickers, kicking one leg up. This slightly awkward self-presentation as ‘babe’ isn’t a one off. She famously posed naked but for a pair of black high heels and covered in dots on her sculpture Accumulation No.2, a phallus encrusted white sofa. Much ink has been spilt by Amelia Jones, in her book Body Art, on deciphering this image, connecting it, as she does to the second wave feminist strategy of foregrounding and acting out the obscured and occluded nature of (sexual) desire which stratifies the field of art. In this image, Jones sees Kusama as making explicit the western desire and fascination for the body of the exotic Other predicated on the apparent modesty and supplication of Oriental women. The artist seems to deny this cliché of the appetitive subordination of (Oriental) women to men – she lies on a phallic field of her own making, she is the mistress of her own jouissance – but the image is also seductive. She can still be enjoyed by an audience who is nevertheless approached and arrested by the usual friction of titillation. Is this just a consumer revolt in the shopping mall of the spectacle, a soft subversion of the status quo?

Image: Yayoi Kusama, I'm Here but Nothing, 2000-2012. (c) Yayoi Kusama. Photo credit: Lucy Dawkins/Tate Photography

There’s a haunting image of Kusama on her arrival in Seattle in 1957 with the gallerist Zoe Dusanne. Both are dressed ‘Japanese style’, in kimonos, in what appears to be Dusanne’s apartment, or a back room of her gallery. The walls are hung with Miro-esque paintings, which could possibly be Kusama’s own work. Kusama looks out like an unwilling accomplice, as her ghoulish patroness apes the Geisha style of makeup, her waspish pearl necklace and earrings offsetting the masque. In the letters displayed in the exhibition, Dusanne’s offer to Kusama of her first show in the States is fleshed out into full mise-en-scene, almost a diplomatic mission of cultural exchange. Having patronisingly suggested that the show should be in spring because her very Japanese patio will be in bloom, she remarks, ‘I have many Japanese friends who would be very happy to wear costumes and serve Japanese tea at the opening.’ With friends like this, no wonder Kusama wanted to self-obliterate! This image registers the length of the journey Kusama had to undertake from such a servile entry into the American art world to her glorious, titillating provocations a decade later. If nothing else, this is a story of admirable self-empowerment, and possibly liberation. What is worth noting, with regards to her use of her own image as ‘babe’, but also as psychedelic priestess or bizarrely wooden fashion model for her own ‘fashion brand’, is the certain indifference which she always expresses. There is a touch of Robert Bresson’s use of actors as blank mannequins, but turned around into a self-use. This indifference is expressed in the title of the show’s penultimate installation (a living room covered in coloured stickers and illuminated with ultra-violet fluorescent strips), I’m Here, but Nothing. In fact the strange dimensional effect of the UV light which only picks up the stickers (think teeth in a night club), thereby throwing the rest of room and its conventionality into semi-darkness, seems an apt metaphor for Kusama’s speculative realism, to abuse a neologism.

‘Consensus reality’ is a ground over which Kusama throws her magic net, but this ground needs to be there to bring her net to life. Her art shifts the focus back and forth between the dematerialisation, or cosmic relativisation of the brutal or banal social field – the domestic space or the city, the orgy or the gallery, the fashion industry or the seduction industry – and its sharpened articulation. It seems to come forward and show its face at the same moment that she makes it recede. Her early ’60s accumulation canvases of air mail stickers and fake money work in just this way; without labouring the point, they attest not only to the repetition-disorder of capitalism, but show how there are other repetitive and accumulative dynamics at play, which underpin but also ultimately dwarf it: those of the libido and the procreant urge of the world. In the words of the great Walt Whitman:

I have heard what the talkers were talking, the talk of the

beginning and the end,

But I do not talk of the beginning or the end.There was never any more inception than there is now,

Nor any more youth or age than there is now,

And will never be any more perfection than there is now,

Nor any more heaven or hell than there is now.Urge and urge and urge,

Always the procreant urge of the world.

– Song of Myself

Josephine Berry Slater <josieATmetamute.org> is editor of Mute and co-author, with Anthony Iles, of the book No Room to Move: Radical Art and the Regenerate City

Info

Yayoi Kusama's exhibition is at the Tate Modern 9 February – 5 June 2012

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com