passed over to a broken machine

Faced with trauma, language’s impoverishment is exposed. Other emotional experiences - love, anger, depression, hunger, or even desire, that infest the body with unfamiliarity, find explication through writing. They begin with a want, so find satiation in language, or at the very least, a sense of control. Faced with trauma, language is depleted into inarticulacy, a muted mess of choked words and insubstantial descriptions. Etymology is useful here: trauma, a physical wound, hurt or defeat, extends from its root, from *trau- to *tere, to turn, twist, pierce or throw. It suggests movement. But language, so dependent upon a stable ground, with rules, directional movement and ends, is unprepared for the sensation of free-fall, of groundlessness, that trauma enacts upon it.

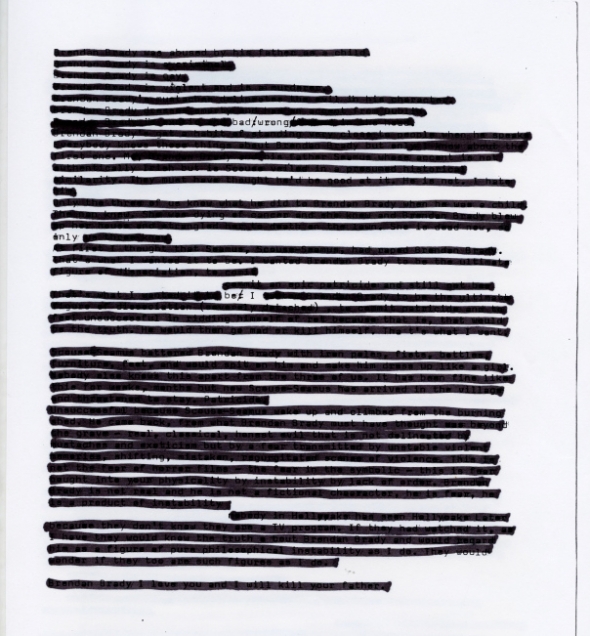

Claire Potter’s Mental Furniture takes language and performs upon it its own failings of articulation. She snatches at the root of the trauma and then treats language with its movement. Trauma is not the event as it is happening, but the resistance that occurs when trying to familiarise the experience within a linear reality. As though a performance of this, the text congeals and chokes, part-wavers and then spills down the page, entire stanzas or explanations ruptured by an urgency to tell. So it makes sense that Mental Furniture was written on a French, non-qwerty typewriter with jamming keys; autonomy gets passed over to a broken machine, one with the appearance of a highly functioning word processor but that, by its own failings, will deliver this resistance between the body and its cognitive decision to articulate. We are not invited to read Mental Furniture, but instead to experience it, uncomfortable: the work is not the book, but its affect. Mental Furniture aims to disrupt the body and temperament, to impregnate familiarity with instability and unease, induce confusion at the very moment remote identification with a character appears. Because the movements are swift and many, grapplings for subjectivity disintegrate, the ground becomes fluid, and we become the puppet hanging over the precipice, suspended.

Or perhaps this is the wrong metaphor. Often there is so much going on, so much repetition, reconsideration, re-wording that you are flailing, not hovering, dragged along a current of incomplete narratives whose cultural references cannot belong to you, as much as they might be familiar. Capitalisations, exclamation marks, spacings expose the immediacy of the text’s construction, that it was written in part, in one go, unedited. Grammar becomes untrustworthy; not decorative, but resistant of traditional use, its rogue interruptions only staggering the forward motion and emphasising the absolute necessity of this deconstruction. The incongruities of form and language expose the performance of writing as a process, afford it a turbulent, emotional consistency only equivalent to the evidence of a trauma. Where memory embodies the same current moment perception does, its recording is an attempt to ground it steady, so it might be judged by another to be true.

To attend to the text is to attend to movement as though taking part in a choreography: a trifold structure, it performs in three parts or fragments. ‘Instigators’ is probably the best way to think of them, three recognisable shapes that appear in the text, that have no known trajectory or footwork, but create connections between thought. The first: a phantom memory, a prototype (?) of an uncertain setting - a description of a mother knelt “before the fire”, before a television set, unmoving, unblinking. A series of memories: the shawl, the face, the plumes of smoke; the mother’s body blocking the heat from circling the room. The second: Brendan Brady, a known character from a British TV drama; a fiction eviscerated, his abused past constructed as a cursive list. None of the confessions offer a conclusion, nor do the three knowing parties - Brendan Brady, the father, the viewer, but Brendan Brady positioned as the object of fear does. The third: A fall to the curb. The collision of two resisting surfaces - skin against body upon concrete and the confusion of limbs.

The three fragments are narrated from different angles, as though different levels of consciousness, or positions of observation. Where they read in sequence at first, stability fractures. The scenes are the memories of an action inherently volatile; they are the product of instability and so disrupt one another, unhinging clear lines of thought with the other’s residual memory. Traumatic repetition performs an almost operational structure of delirium; displacement and dissimulation never recreating memory with clarity, only developing the desire to remember. But why remember? Roland Barthes claimed that before trauma, language was suspended and signification blocked, yet found clarity through images. To render something visually makes it close to material in its proximity to the symbolic. To render something visually gives you something near-physical to destroy. If we are to believe Michel Foucault, subjectivity shares a tri-fold structure; it exists as the balance of three equivalent parts: subjectivity that categorises, distributes and manipulates; subjectivity through which we have come to understand ourselves scientifically, and subjectivity that forms ourselves as meaning. A triangle of substantiation is a precarious shape, dependent upon balance. Faced with trauma, subjectivity is at stake. Mental Furniture extracts one limb, removes ourselves as meaning, and allows the other two to fall naturally. We think we know Brendan Brady, because we are trained to want to identify with something/someone in the text. We think we know Brendan Brady because he is a celebrity, but he is also a character, and an actor, and a person in himself. Brendan Brady is a leading fiction in a late-night TV programme, but he is unknown to those characters in its day-time version. And he is also a character of Claire Potter’s making, or through the eyes of her character as author watching him. Brendan Brady is a fictional body, a vessel ‘put into action’ by a system of belief and over-identification. Brendan Brady does not exist as a symbol of his trauma, he becomes his trauma.

But I want to return to movement, the condition Potter treats language with. Trauma: *trau- to *tere, to twist or throw. To experience Mental Furniture is to be thrown by language. Patterns and recognisable phantom figures do appear as though intentional - dirty rabbit, the mother, water - but their presence is dependent upon a complex chaos of shifting time, and they rely upon this undoing. They punctuate the text like talismans, offering resistance, temporary steadying, recognition even. Then there are sections of fervent articulacy, where anger and fear crystallise and deliver something vicious, something potent. But where does that leave us, the readers? We have no place in this chronology, yet experience its effect and its destruction externalised upon the page. This is not a text without plot, but a text about movement between memories, and about that movement. It has similarities to literary mechanisms used by the Nouveau Romanciers, and especially to Nathalie Sarraute’s ‘tropisms’—“interior movements that precede and prepare words for action at the limits of our consciousness,” into which subjectivity disintegrates. Yet the objective of that technique was always directed towards the character, it did not target the reader. Mental Furniture invites us in and then swiftly removes our grounding; we are on the inside of a trauma that does not nor cannot belong to us. We are below water, our subjectivity dissolved, moving.

Article originally published here:

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com