Unhoming the Homely

Clare Butcher reviews Casco's ambitious two year and ongoing project, the Grand Domestic Revolution

Having emerged as a response to Utrecht Manifest in 2008, the Grand Domestic Revolution, (GDR) coordinated by Casco Office for Art, Design and Theory, has evolved as a research and residency platform ‘exploring the urgent domestic concerns of today and the potential transformative ways to engage them.’ Borrowing the ‘material feminist’ Dolores Hayden’s concept, the GDR (not to be confused with other historical geographic acronyms) seeks to expand the sphere of the domestic, as well as perhaps revitalising the term 'revolution' itself, as of May 2011.[1] The closing manifestation of the GDR produced a multi-sited show, ‘The Grand Domestic Revolution – User’s Manual’ of more than 40 artists which ran from November, 2011 to February, 2012. The works included are meant to give form to the questions of why and how to create a domestic revolution, while also reflecting on the many research trajectories taken along the project’s two-year run. Intended to be not just illustrative, the exhibition’s curators hoped that visitors would also be led to question their own homes and backgrounds.

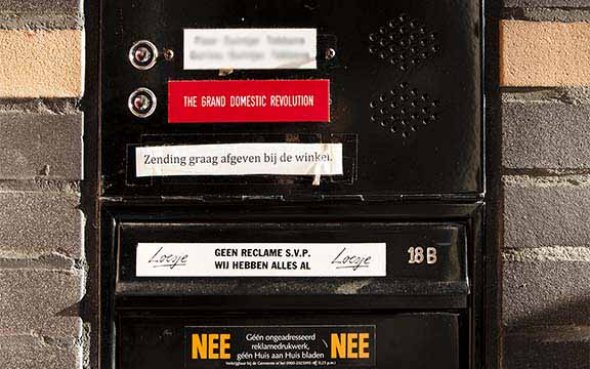

Staging such an exercise as an exhibition brings with it a whole history of productive tensions between private and public. Tony Bennett, whose writing around the great exhibitions in many 19th century metropolises is well-known, frames such events as didactic machines, providing ‘object lessons’ to viewers with the expectation that they would at some point recognise themselves as part of a civic mass – an urban community. While far from being a Crystal Palace, the semi-transparent blue plastic wooden shed, designed by Ruth Buchanan and Andreas Müller (who were responsible for the exhibition’s structures in general), appended to the outside of one of the GDR exhibition venues –Utrecht’s Volksbuurt Museum – made me think once again about those ‘object lessons’. The shed also used the language of the great exhibition, calling itself a 'pavilion' of the 18b apartment where the GDR had been stationed. Within this makeshift structure – an obvious incursion into municipal architecture by-laws – the curators saw fit to annex a number of traces and tools in archival tribute to the research done by the apartment’s many residents. While my own art historical frame of reference may seem overdetermined, I was struck by the difficulty of constituting a public for a work executed or intervention made, long after the fact itself.

And, indeed, much of the exhibition occupied that same uncomfortable terrain between documentation and domestic proposition. A provocative example of this is the Centre for Cooperative Living (2010) devised by the curator Sepake Angiama with architect Sam Causer and artist Doris Denekamp. For this, the makers devised a rendition of the popular local communal garden – intending it as a platform for neighbourly interaction on the balcony of apartment 18b. While the structure was never actually realised by tenants or neighbours, the blue 'greenhouse' constructed by Buchanan and Müller seems an appropriate incubator for the Centre’s future realisation.

This reticence by the City of Utrecht towards the, sometimes, unfamiliar level of engagement invited by the GDR, allows perhaps for another riff on the metropolitan phenomena of the 19th century. It was at this time that literature introduced to the domestic space the notion of the 'uncanny'. In a city of strangers, the homely interior could be easily and dramatically contrasted with the ‘invasion of an alien presence’.[2] That alien presence was very much class and, therefore, labour related. And in a sense the GDR has taken that notion uncannily to heart, making its alien presence felt (subtly and at other times more obviously) in its various exhibition locations: at Casco’s own headquarters, the established Left-hand bookshop, De Rooie Rat, and as mentioned, the city’s neighbourhood museum/archive, the Volksbuurt Museum.

While poetic, the decision to spread the exhibition over multiple venues is also logical, in keeping with nature of the GDR’s second year of research. During this period Casco’s coordinated activities moved further afield, away from the apartment, honing their focus while also drawing attention to new sites of concern. These concerns are marked by the exhibition’s four themes:

1. Domestic space: housing the commons and living together

2. Domestic work: invisible labour and working at home

3. Domestic property: struggles between ownership and usership

4. Domestic relations: extended families, neighbours versus networks

Perhaps the success of the GDR as an exhibition lies in its unhoming of such broad theoretical frameworks, situating them within disparate, though otherwise familiar contexts. One should remember that the unsettling capacity of the uncanny is due to its similitude to the thing next to or in front of it which, according to contemporary psychoanalysts, results in estrangement.

This making strange the homely, and vice versa, is played out in amongst the Volksbuurt Museum’s historical neighbourhood treasures where, for instance, we find an intrusive open-topped wooden box containing Kateřina Šedá’s ‘social game’, There’s Nothing There (2003). Šedá’s installation comprises video and paper documentation of a project done in the Czech town of Ponětovice, where the artist dictated a regime of banal exercises based on the inhabitants’ daily activities. Some earlier student works by Šedá could be found, subtly hung in the museum’s stairwell. These ‘domestic burning acts’ are drawings made on bed sheets using a hot iron. The drawings’ quiet modesty provided an aesthetic respite from the overload of multimedia museum displays and the unflinching sociopolitical commentary of other GDR works such as the shadow play film collaboration between the Domestic Workers Netherlands and Matthijs de Bruijne, I Will Not Ask Anything About You, You Will Not Ask Anything About Me (2011). This ten-minute musical, well produced and presented in the museum’s darkened upstairs gallery, exposes the unseen, uncanny, presence and work of immigrant labourers in domestic spaces. For many viewers this was perhaps a bit too close-to-home for comfort.

Perched next to the most recent edition of David Harvey’s book, The Enigma of Capital, in De Rooie Rat, are still more projects produced during the course of the GDR as well as historical case studies which serve to contextualise the works in a longer history of urban/domestic investigation. Gordon Matta-Clark’s Reality Properties: Fake Estates, ‘Jamaica Curb’, Block 10142, Lot 15 from 1978, presented as, in the words of the exhibition map (designed by Åbäke) a facsimile of collaged gelatin silver prints underneath a glass top, advocates the claiming of inutile urban space between buildings by communities for purposes other than ‘development’. These documents slip subtly into the visual language of the bookshop, similar to two newer works by Emilio Moreno. In Other Issues (2011) Moreno’s research, some of which was conducted while in residence at the GDR apartment and investigates the use of alternative currencies within domestic systems of trust, is presented in elegant booklets laid aside the cash register. According to the artist’s instructions, all bank notes exchanged by the bookshop during the period of the GDR exhibition were to be stamped with an additional short story, Battle Poetics (2011), thus entering Moreno’s commentary into proper economic circulation.

In the Casco head office, Ruth Buchanan and Andreas Müller’s staging of the exhibition is made the most apparent. Here, a sunny yellow theatrical curtain conceals the tireless Casco team and their '9 to (never quite finished)' office hours. This was an intriguing decision and while a large mirror opposite the curtain promises a direct self-reflexivity, this part of the object lesson was, in a sense, the most difficult to read. In front of the mirror, a video produced by Maria Pask, Nazima Kadir and what they call, ‘an evolving cast’ and list of scriptwriters, entitled Our Autonomous Life? (2011-12) plays on a floor-level monitor. Taking up recent debates around the Dutch housing situation, the footage produced is a disorienting, experimental ‘cooperative sitcom’ based on the experience of a fictional group living in a communal house. Filming of the sitcom continued into and after the exhibition, and following its final screening in April, 2012, a forum entitled ‘Let’s Squat Something!’ was hosted by Casco around the question of whether squatting should and could continue in the Netherlands.

A host of activities remain in the months following the GDR exhibition’s closing, including a future fiction-writing workshop, read-in session and an issue of a collaborative edition of Werker Magazine. The broadcasting of Our Autonomous Life? on local TV station, UStad/RTV, and subsequent publications by the GDR are very much a part of the grand finale of a grand revolution. It is now up to the archive to infiltrate and unsettle not only familiar domestic domains, but to enter into disparate, yet homely private settings – constituting new publics across multiple dinner tables.

Clare Butcher (ZW) is a curator and writer currently researching exhibition histories at the University of Cape Town. She also cooks

Info

The Grand Domestic Revolution: User’s Manual Exhibition took place in various sites around Utrecht, Nov, 2011-Feb, 2012

Footnotes

[1] Hayden's book was a major inspiration for the show. Doris Hayden, The Grand Domestic Revolution: A History of Feminist Designs for American Homes, Neighborhoods, and Cities, MIT Press, 1981.

[2] Anthony Vidler, The Architectural Uncanny, MIT Press, 1992.

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com