Origin and Extinction, Mourning and Melancholia

If extinction is inscribed into and necessary for the emergence of life, how, asks Nathan Brown, can we ever integrate the mourned object into our material lives? And what part, if any, can cinema play in this mediation?

The true health of spirit consists in the perfection of reminiscence.

– Arthur Schopenhauer

The Passion of Modernity: Malick’s The Tree of Life

What is the vocation of cinema? To make visible, in time, that which is invisible outside of cinema. This is why it rains indoors in Tarkovsky's films: the interior visibility, as image, of what had been invisible (memory, desire) insofar as it remained outside of cinema. Cinema makes visible, as image, its invisible outside. But what then remains invisible, inside of cinema? The experience of cinema, which we carry back outside. A chiasmus, then, of the visible and the invisible, the inside and the outside. Interior rain: memory made image; image, remembered. And the medium of this chiasmus is time.

But what of that which, outside of time, cannot be remembered? From the beginning, Terrence Malick’s films have been posing this question. In Badlands (1976): 'Where would I be this very moment if Kit had never met me? If my mom had never met my dad?'

And what of that which is neither visible nor invisible; manifest, yet unknown? In Days of Heaven (1978): 'This farmer, he didn’t know when he first saw her, or what it was about her that caught his eye. Maybe it was the way the wind blew through her hair.' In The Thin Red Line (1998): 'What’s this war in the heart of nature? Why does nature vie with itself? The land with the sea?' In The New World (2005): 'Mother, where do you live? In the sky, the clouds, the sea?' Or again: 'How much they err that think everyone which has been at Virginia understands or knows what Virginia is.' Malick’s is a cinema of an unknown that is sensed, and the vehicle of this not-knowing is the voiceover, the musing of an unseen speaker, the disembodied question.

But what of that which is not only unseen or unknown, but which could never be manifest? That which, in time, is not only prior to memory, but prior to manifestation? Not only prior to the distinction between the visible and the invisible, but prior to sensation, to any capacity for sensible experience? What is the vocation of cinema, if it takes up this question? To make manifest, in time, that which is prior to manifestation.1 The task of Malick’s new film, The Tree of Life (2011) chimes with the epigraph from the Book of Job: 'Where were you when I laid the earth’s foundation […] while the morning stars sang together and all the sons of God shouted for joy?'

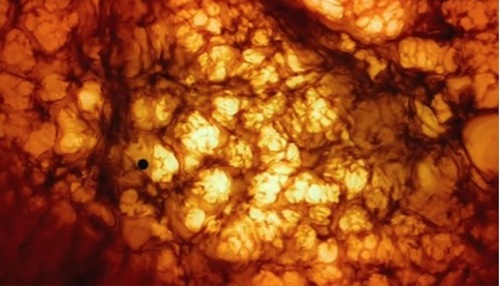

Image: Terence Malick, Tree of Life, 2011

The Tree of Life circulates around a central, singular event: the death of a son, an event that entails the mourning of that death by a mother, a father, and two brothers. But this event – the fact of a death and the experience of loss, situated at an existential and psychological level – opens onto a meditation upon another event of properly ontological import: the emergence of life on earth. A son dies; he is mourned by his family. And on the anniversary of his death, decades later, the film’s narrative focalisation upon the psychological interiority of his older brother gives way to one of the most remarkable 'flashbacks' in the history of cinema, even more grandiose than the famous analeptic cut which opens 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). From outside the office building where the eldest brother now works as an architect we return to what seems to be the origin of the cosmos, and from here we follow the expansion of the universe and the formation of our galaxy through the accretion of the earth, millennia of geological time, the self-organisation of RNA and DNA molecules, the emergence of mitochondria and multicellular organisms, the evolution of diverse animal species during the Cambrian explosion, the reign and extinction of the dinosaurs, and the beginning of the latest ice age during the Pliocene. We then return to the bildungsroman of the eldest son, following the progress of his family romance up through the years preceding his younger brother’s death.

Image: Terence Malick, Tree of Life, 2011

The film thus situates not only the mourning of a lost life but also the development of a family’s affective world within the broadest possible perspective. The particularity of a life that can be lost takes on the universal singularity of a life (Une Vie, in Deleuze’s sense). The scope of a particular loss to be mourned expands to include the emergence of life on earth as the condition of possibility for any affective experience of loss whatever. The implication of this gesture is not so much that 'loss' is the essence of life, but rather that the existence of life is the essence of loss. The 'meaning' of the affective experience of loss is grounded in the very existence of affectivity or experience, the existence of life, felt or understood as the ontological precondition for the possible negation of affect, sensibility, or experience (the possibility of death).

Image: Terence Malick, Tree of Life, 2011

Malick’s film is thus one example of an effort to reframe existential questions concerning the relation of life and death as ontological questions concerning the being or non-being of life per se. It is an important film not only because it is beautifully made but because of the subtlety with which it exposes the problematic of living as being both physical and metaphysical in scope. The being of 'life' is a metaphysical problem because unless life is metaphysical it has no being: it is reducible to the material distribution of organisations and functions that neither warrant nor support a general, encompassing concept. Every vitalist knows this, and that is why, for example, it at least makes sense to recognise the coherence of the Deleuzian concept of a life, even if one does not share his metaphysical commitments. But, on the other hand, if 'life' is purely metaphysical it has no being. Life is a physical problem because it characterises the modality of being of material bodies whose properties and capacities differ from those of non-living bodies: even if, in certain instances, it turns out to be surprisingly difficult to specify just how this is the case.

Image: Terence Malick, Tree of Life, 2011

In Malick’s film, the ontological and existential problem of 'life' is taken up within a Christian framework, which therefore involves him with the problem of not only life, but of spirit. We should bear in mind, however, that this framework is not necessarily that of the film itself but rather of the characters whose lives it depicts. If The Tree of Life remains a profoundly materialist film, it is because the existence of spiritual experience is itself addressed as a problem of material genesis: how does spiritual experience – as an existential fact, as part of a world – come into being within the cosmos? In what sense can we understand the emergence of life as an ontological condition of such experience? And how does the work of mourning pose the question of the relation between spirit, life and matter, insofar as it involves an affective relation to the material disappearance of a life experienced as a spiritual loss? Malick’s characters respond to the loss of a life by posing spiritual questions and seeking their spiritual resolution. The film’s representation of the 'tree of life', however, the physical genesis of living being, implicitly responds to these questions in explicitly materialist terms. It is a resolutely Darwinian film, but one that includes the existence of spiritual experience as a fact, and thus includes it within the process of material genesis that it seeks to make manifest through cinematic representation.

Image: Terence Malick, Tree of Life, 2011

Materialism is that philosophical orientation which formulates ontological questions according to the following criterion: given that being is prior to thinking, how can thinking become adequate to being? In Malick’s film, as its title suggests, this problem is crucially conditioned by the mediation of the relation between being and thinking by life, and therefore by affectivity and sensation as conditions of material experience. Moreover, insofar as these conditions (feeling, sensing) give rise to forms of spiritual experience, affectivity not only constitutes the distinction between matter and life or grounds the relation between life and thought, it also gives rise to a relation between life and spirit. It is thus a spiritual problem which returns us to the 'tree of life' in Malick’s film, to the genesis of affectivity. It is a spiritual problem that returns us to the question of how feeling and sensation first come into being, of how the opacity of being opens onto manifestation for the first time. If affect and sensation first come into being through the existence of life, how can this becoming-sensible itself be made sensible? Which also means: how can it be felt, how can it be made to affect us? And what becomes of cinema in its effort to make manifest that which is prior to manifestation?

The most obvious fact about Malick’s film, but also perhaps the easiest to overlook in parsing its commitments, is that the capacity of cinema to address these problems is first and foremost a technical capacity. If the spiritual, existential, and ontological questions posed by the voiceover of Malick’s characters might seem to be answered by the 'god’s eye view' of the camera – its capacity to frame and render visible the material genesis of the cosmos – we should remember that this is in fact a technical frame. It is a frame wrought by a production team faced with immediately material problems of visual representation solved through the resources of current biological and physical theory, scientific visualisation techniques, 3D scanners and CGI special effects. Which also means that these are solved through considerable financial resources: by capital.2 What has to be thought, in thinking through Malick’s film, is the fact that the gleaming corporate skyscraper of the architectural firm for which Sean Penn’s character works, his late capitalist life-world, is also the context in which a film like this is engineered and paid for. It is not, directly, life or thought or spirit that enables the manifest reconstruction of the material coming-into-being of manifestation; it is technics. In this sense, the true frame of The Tree of Life is not so much a Christian theogany as a late capitalist anabasis, a return to the source of all that modernity allows through its scientific, technological and economic resources. The problem, then, is not only that of the relation between matter, life, thought and spirit, but how this relation is mediated by technics and by capital.

This is not, of course, to undermine the integrity of Malick’s project, but rather to think its situation, the manner in which its own conditions of possibility are inscribed in those of cinematic representation at the beginning of the 21st century. If the perfection of reminiscence is, for Schopenhauer, the true health of spirit; for cinema the effort to remember everything returns us, at its limit, to the restlessness of spirit afflicting each of Malick’s films: that of a garbage man, a factory worker, a soldier, a colonist, a corporate architect. This is the restlessness not only of what we do not know but also of what we know too well, not only of the beginning but the end, not only of the origin of life but of life under capital. The cinematic perfection of reminiscence is thus the passion of modernity, made manifest.

Image: Lars von Trier, Melancholia, 2011

Hiding Behind the Sun: von Trier’s Melancholia

Kassandra: look the

cup of my pain is already poured

out why

did you bring me

here was

it for this

was it for this

was it for3

In the Agamemnon of Aiskhylos, Kassandra knows that she will die. It is her own death she mourns, before it happens. She mourns the particularity of a death that distinguishes her from those who will go on living:

But yes think oh think of the clear

nightingale—

gods put round her a wing

a life with no sting

but for me waits

schismos

of the double-edged sword: schismos

means

a cleaving a cutting a splitting a

chopping in two4

She laments her imminent separation from the world of the living, which doubles a prior separation from her home:

O marriage of Paris so deadly for everyone

else

O river of home my Skamander

I used to dream by your waters

now soon enough

back and forth on the banks of the river of

hell

I will walk with my song torn open5

The living are distinct from the dead ('everyone / else') and Kassandra is doubly distinct among the living: first, because her death is imminent; second, because she knows this. Because she is a prophet. Thus she will die when the present catches up with her proleptic knowledge of the future, and what she knows will vanish, in time, into her own death. Death, for the prophet, is the restitution of a rift in time.

Mourning and Melancholia

In 'Mourning and Melancholia', Freud describes melancholia as the introjection of a lost object, and of one’s ambivalence toward it.6 The ego is split, divided, torn open by the internalisation of an irrevocable absence. Schismos, Kassandra says. Cleaving: an attachment that cuts. One is divided by that from which one cannot divide oneself, though it is already gone.

Image: Lars von Trier, Melancholia, 2011

Elektra is a melancholiac. In the play by Sophocles she has a sister, Chrysothemis, who accommodates herself to the loss of their father. Elektra cannot:

You are women of noble instinct

and you come to console me

in my pain.

I know.

I do understand.

But I will not let go this man or this

mourning.

He is my father.

I cannot grieve.

Oh my friends,

Friendship is a tension. It makes delicate

demands.

I ask this one thing:

let me go mad in my own way.7

I cannot grieve. Insofar as she will not let go her mourning, she cannot mourn. The work of mourning is inoperative. Insofar as it is without end it cannot begin. Melancholia is this self-negation of mourning, and the vector of this self-negation is the negation of the self: either madness or suicide. These are the only possible termini of an interminable self-negation:

Never

will I leave off lamenting,

never. No.

As long as the stars sweep through heaven.

As long as I look on this daylight.

No.8

Friendship is a tension, and from her friends Elektra asks allowance to go mad in her own way. From herself, as the soliloquy above implies, she seems to want permission to black out the sun and the stars. There is also a cosmological request implied in this passage: for the stars to stop their courses; for the sun to stop shining. For relief of her condition by some kind of planetary or astral catastrophe. The shattered ego wants a broken heaven and a black sun. Suicide, then, or apocalypse. But if the latter, it could never be revelation; only a negation: 'No.' It could only be an annihilation of self and world from which nothing could come. Melancholia is an attachment to an absent past (a lost object) issuing in a rejection of the future and a hatred of the present. The analepsis of the melancholic is not the negation of prolepsis but a negativity internal to it, the 'no' of 'no future' installing itself in the now. And this is a splitting of the ego, a fracture, or void, torn by the torque of time. Madness: an interior undoing of this fracture, its psychic rupture. Death: an exterior negation of an interior void, the dissolution of its boundary. Death, for the melancholiac, is the dissolution of a rift in time.

Melancholic Prophets

Prophecy reverses the temporality of melancholia: the melancholic prophet proleptically interiorises the future loss of her own life – a loss which, in prophetic time, has already happened, so that it can happen to her, now. She not only lives her being-toward-death, in the existential mode of projective anticipation. Insofar as she already knows when and how she will die, she anticipates nothing. She is not torn between thrownness and projection, between being-in-the-world and being-toward-death, historicality and anticipation. Rather, these have collapsed: what happened yesterday is that she died tomorrow. Their collapse is not 'ekstatical' but introjective, and this introjection or interiorisation structures the melancholic Stimmung of prophetic time.9

The melancholic prophet interiorises an ambivalence toward her own death, a temporal ambivalence which is split, torn, divided, torqued. It is temporally and affectively divided (ambivalent) because the death of the prophet is at once the beginning and the end of melancholy. One loves one’s death because it is the terminus of melancholy; one hates one’s death because it is the origin of melancholy. In a word, death is the telos of melancholy, and this telos is ambivalent. The sharp edge of its ambivalence, carving a difference between the beginning and the end, is knowledge. The proleptic having-happened of one's own death is what one knows, in the present. And death will be the end of this knowing, its coincidence with being nothing.

Time is a line upon which a fracture displaces itself: from Aristotle to Heidegger and Deleuze, philosophy has always known this. The moment of my death is that at which I come to know nothing of this displacement, at which I no longer know what becomes of time. Ignorance, says Lacan, is the strongest of the passions. All passion spent, the melancholic prophet is the one who cannot not know, who cannot be ignorant. The ambivalence of the melancholic prophet toward her destiny derives from the fact that her only access to the passion of ignorance is death, oblivion, and thus the dissolution of all passion. The ambivalence of her destiny resides in a complicit tear between knowing and not-knowing, restitution and dissolution.

In Lars von Trier’s Melancholia, Justine is just such a melancholic prophet. Kassandra/Elektra: Justine. What does she know? What has she lost?

The latter is the diagnostic question raised by the Freudian theory of melancholia: what is the lost object that cannot be let go, which has been interiorised along with one’s ambivalence toward it? This question threatens the account of the melancholic prophet offered above with incoherence. For foreknowledge of one’s own death does not necessarily entail a lost object, retrojected into the present tense so as to provoke its ambivalent introjection. One’s own death is a loss without object, since 'life' is not an object to be lost.

In the case of Melancholia, however, the question begged by Freud’s account yields a precise answer: the lost object is none other than the earth itself. This is a loss that can only be lived proleptically, since the loss of this object, its annihilation, would coincide with the death of any subject to whom it could be lost. As the exterior object is lost, the interiority that could register this loss is annihilated. It is the introjective knowledge of this double eradication, in the present, that precipitates a proleptic melancholy.

Thus we can say that the subject of von Trier’s film is not only prophetic melancholia, but the relation between melancholy, prophecy and extinction. Justine not only knows that she will die, but that her death will coincide with the end of the world. Not only her world, but the world. The annihilation of world, insofar as the existence of life on earth is the condition of possibility for the phenomena of world. Along with everyone else, she will die as the world ends; unlike everyone else, she knows this now. She does not know this as a scientific prediction or a speculative hypothesis, but prophetically: as something that has already happened though it has not happened yet.

Image: Lars von Trier, Melancholia, 2011

This is precisely the formal structure of von Trier’s film. It opens with a series of tableaux which are not quite still but barely moving, captured in extreme slow motion. A close up of Justine’s face as dead sparrows fall to the side of her gaze. A woman carrying a child, running across a golf course as though through quicksand, her feet sinking into the ground. A bride, a boy, a woman on the lawn before a castle at night, walking into the foreground, each figure attended, above, by an astronomical counterpart: a blue planet, a crescent moon, a pale sun. A boy carving bark from a stick with a pocketknife as a woman approaches through the grass. A bride trudging, in profile, across a field in front of a wood, dragging heavy woollen ropes bound to her arms and legs, attached to the trees in the background. A massive blue planet approaching the earth, devouring it in a collision. 'Melancholia', it will come to be called.

The beginning of the film thus reveals its ending, makes manifest what will never be perceived (within the world of the film) insofar as it is the end of all perception. For Justine the end of the world will be the negation, the non-being, in the now, of knowing what will be. The seamless folding together of form and content in von Trier’s film is such that the now of this ending is both the beginning and the end of the film. As the incendiary shockwave of a planetary collision devours the frame, as though burning up the screen, the screen cuts to black. Before the end, the melancholic prophet is afflicted not so much by her knowledge of this ending, but by the fact that this knowledge has not yet ended. This structure is recapitulated for the audience not as affliction but as dramatic irony, the narrative tension of a proleptically dissolved suspense. Thus the ending of the film is a kind of meta-filmic resolution, the restitution of a rift in time that is also the dissolution of the medium. The earth is destroyed, the screen blacks out, what had already happened has happened. Melancholia is over. The credits roll.

This complicity of prophecy and dramatic irony – content and form fused by proleptic temporality – is the meta-theatrical structure of Greek tragedy. It is the structure of anankē.10

Like Elektra, Justine has a sister. And like Chrysothemis, Claire councils accommodation to the order of things. A sensible girl, she does not want any 'scenes' at Justine’s wedding:

Here you are again at the doorway, sister,

telling your tale to the world!

When will you learn?

It’s pointless. Pure self-indulgence.

Yes, I know how bad things are.

I suffer too – if I had the strength

I would show how I hate them.

But now is not the right time.11

Like Chrysothemis, Claire is pragmatic. Like Elektra, Justine is inconsolable. She cannot force herself to endure the ceremony of false or inessential or superficial affective attachments because in the dead time of prophecy every attachment is already broken. On their wedding night her husband shows her a picture of an orchard he has just acquired ('I found our plot of land', he says), imagining that one day they might hang a small swing from an apple tree. 'We’ll talk about that when the time comes', she says, knowing that it won’t. Because it ultimately makes no difference there is no reason to consign one’s life to semblance, and she can’t, even if she has to perform it sometimes. What remains is not so much pessimism as a bitter authenticity.

Image: Lars von Trier, Melancholia, 2011

The lost object is what one loves; because it is lost, one hates it. Internalised, the ambivalence of this affective bond gives rise to an irrevocable attachment of self-loathing and narcissism, a riven solipsism as petty and cruel as it is admirable in its loyalty to the truth of what one feels. Disdaining the other, insofar as she does not suffer from this double bind, one is also hated for an intransigent honesty. 'You know what I think of your plan?' asks Justine when Claire wants to mark the imminent annihilation of the planet with a glass of wine on the terrace: 'I think it’s a piece of shit.' 'You appall me', Elektra tells Chrysothemis.12 'Sometimes I hate you so much', Claire replies.

Recrimination, refusal to mourn, fidelity to the impossible: these are the hallmarks of melancholic ambivalence. 'The earth is evil', Justine tells her sister. And then, 'life on earth is evil', a sliding precisely expressive of recriminatory identification with the lost object. 'We do not need to grieve for it', she concludes. 'Nobody will miss it.' The rejection of mourning for the earth, an introjected hatred of the object that will be lost, also entails an ambivalent longing for the agent of its loss. This is the source of Justine’s erotic identification with the planet, Melancholia, which bears the name of her sickness: she offers herself, naked, to its light. Until the earth is destroyed, Melancholia is the proleptic agent of its loss. After the earth is destroyed, loss itself has been annihilated. There is thus a crossing, a collision, at which the 'lost' object gives way to the object, absent any subject or affective investment. The ambivalent introjection of what will be lost is also a longing for the eradication of loss itself. What had been an affective condition (melancholia) tied to the lost object will simply be an object (Melancholia) and even its name will die with those who knew it. The object destroys both the reason and the capacity for its nomination.

Image: Lars von Trier, Melancholia, 2011

One of the veils of inauthenticity that melancholia tears through is denial. Claire’s attachment to the earth is not ambivalent, but immediately positive. Justine 'knows things', but when Claire eventually knows the fate of the earth she cannot incorporate this knowledge. 'Nobody will miss it', Justine tells her. This is literally true, but for Claire the force of this truth, the destitution of nobody, is unthinkable. 'But where would Leo grow up?' she replies. Whereas attachment to her son’s life, which for her is not yet lost, dominates the interior of Claire’s psyche, Justine has already interiorised the extinction of interiority. The impossible structure of her psyche is the introjected erasure of the boundary between interiority and exteriority, a boundary constitutive of affective life. Justine doesn’t just know how many beans the guests poured into a bottle at her wedding; she knows that 'We are alone. Life is only on earth. And not for long.' What is unthinkable is not so much that the earth will be destroyed, that 'we' will be gone, that 'nobody' will remain, but that the universe will remain in the absence of experience and affectivity. This is the unassimilable truth of extinction.13

If one thinks of classical tragedy, of Kassandra and Elektra, it is because von Trier’s film evokes the world and the mood of myth. Claire peers through the foliage at her sister’s naked body, stretched out at night across the rocks beside a stream, ravaged by the blue light of a fatal planet. The first half of the film is dominated by ritual, a lavish wedding that will come to nothing because the bride cannot bear pretence. The setting is a palatial estate, on the grounds of which is not a labyrinth but a golf course. Twice, Justine’s horse will not cross the bridge over a river; the third time a golf cart will not do so. 'Nibiru', an Akkadian word meaning 'crossing' or 'point of transition', is the name assigned by doomsday prophets to the hypothetical undiscovered planet from which the film draws its apocalyptic scenario. At the end of the world and the end of modernity our relation to ritual, to ceremony, to nobility, and to myth is for the most part bathetic. Insofar as Melancholia is a comedy of manners it is also the tragedy of what Theodor Adorno would call 'a damaged life'.14 Frequently amusing, ultimately it isn’t funny. And the ambivalence of the film’s black humour, an ambivalence operative at the level of mode, is also melancholic.

The final sequence of the film, however, involves something like a recuperation of ritual, of collective ceremony. Claire’s husband tells their son there will be nowhere to hide if the planets collide. But what he forgets, Justine reminds her nephew, is 'the magic cave.' The somewhat menacing tableau at the beginning of the film – a boy carving a branch while a woman with a dire expression approaches from behind, wielding a stick – is in fact a premonition of its most tender scene: Justine distracts her nephew from the coming catastrophe by helping him construct a small teepee in which he and the two sisters will await their death. Whatever comfort remains at the end of the world has nothing to do with the comforts of modernity: the electricity fails, the phone is dead, the car won’t work, a golf cart shuts down. Rather, all that remains is nature and myth: not a glass of wine on the terrace, but the magic cave. Juxtaposed against the fake formalities of the wedding, the authentic ceremony of the film’s conclusion entails a modal dialectic of black comedy and tragic catharsis, the beautiful and the grotesque, jaded nihilistic pessimism and the innocence of magical realism. Apocalypse reveals nothing – other than the comportment we adopt toward it, the resources with which we confront it.

The problem of von Trier’s film is thus ultimately the same as that of Malick’s The Tree of Life: no less than the problem of the relation between matter and spirit. In their treatment of this problem, the two films are practically mirror images. Malick’s film is concerned with the origin of life; von Trier’s with its end. The narrative motor of The Tree of Life is analepsis; that of Melancholia is prolepsis. The materialism of Malick’s film strains against its dalliance with Christianity; that of von Trier’s film against its pseudoscientific scenario. But both are concerned with the affective experience of loss, with the material conditions of possibility for such experience, and with the hope of spiritual restitution through collective ceremony. Perhaps also, at a meta-filmic level, through aesthetic experience. In a word, one is a film about mourning; the other is a film about melancholia.

Image: Terence Malick, Tree of Life, 2011

And insofar as one is concerned with ancestral time, the other with the time of extinction, both are concerned with the problem of dia-chronicity: of a temporal disjunction between being and thinking.15 Life and mind, feeling and thinking, have a beginning and an end, and since these do not correspond with that of the cosmos, to think their origin is also to think what remains after their negation: material oblivion. Thus von Trier’s film answers Malick’s, insofar as it is not the affective projection of a world beyond (heaven) that enables something like spiritual restitution, but rather the imminence of the end of the world, without experiential remainder. A confrontation with this ending – at an ontological rather than an existential level – is what makes possible whatever collective communion takes place in Melancholia: the being-in-common of what has not always been and what will not always be.

But what does it mean, for a materialist, that at the end of this film the imminence of extinction is the condition of possibility for spiritual restitution? It means that, at the end of modernity, we will not survive the advent of everything we have always wanted, which has been hiding behind the sun.

Nathan Brown is Assistant Professor of English at UC Davis, where he also teaches in the Programs in Critical Theory and Science & Technology Studies. He has published articles on philosophy and critical theory, poetry and poetics, and science and technology studies in Qui Parle, Radical Philosophy, Parallax, How2, and Jacket, as well as chapters in The Speculative Turn (re.press 2010) and The New Whitehead (Minnesota University Press, forthcoming 2013)

Info

Terence Malick, Tree of Life, US, 2011. Lars von Trier, Melancholia, Denmark, 2011.

Footnotes

1 On 'the paradox of manifestation', see Quentin Meillassoux, After Finitude: An Essay on the Necessity of Contingency, Ray Brassier (trans.), London: Continuum, 2008, p.26 and p.123. Meillassoux's work has been important to my thinking in this piece insofar as he is concerned with the problem of 'dia-chronicity', the temporal discrepancy between thinking and being involved in statements about or representations of events prior to the origin of life or ulterior to the extinction of the human species. See: p.112.

2 It should be noted that Malick worked with a visual effects team led by Douglas Trumbull and Dan Glass to create much of the natural science sequence of The Tree of Life without the use of CGI. Trumbull describes the process as follows: 'We worked with chemicals, paint, fluorescent dyes, smoke, liquids, CO2, flares, spin dishes, fluid dynamics, lighting and high speed photography to see how effective they might be […] It was a free-wheeling opportunity to explore, something that I have found extraordinarily hard to get in the movie business. Terry didn’t have any preconceived ideas of what something should look like. We did things like pour milk through a funnel into a narrow trough and shoot it with a high-speed camera and folded lens, lighting it carefully and using a frame rate that would give the right kind of flow characteristics to look cosmic, galactic, huge and epic.' Douglas Trumbull quoted in Hugh Hart, 'Tree of Life Visualizes the Cosmos Without CGI', Wired, 17 June, 2011, http://www.wired.com/underwire/2011/06/tree-of-life-douglas-trumbull/. However, Malick does make use of CGI graphics in the dinosaur sequence of the film, as well as the digital resources of scientific visualisation laboratories for the film's representations of molecular biology. The budget of the film was estimated at $32,000,000, http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0478304/.

3 Aiskhylos, Agammemnon in An Oresteia, Anne Carson (trans.), New York: Faber and Faber, 2009, pp.51-52.

4 Ibid., p.52.

5 Ibid., p.53.

6 Sigmund Freud, 'Mourning and Melancholia' in Murder, Mourning, and Melancholia, Shaun Whiteside (trans.), New York: Penguin, 2005, pp.201-218.

7 Sophocles, Elektra in An Oresteia, Anne Carson (trans.), New York: Faber and Faber, 2009, pp.93-94.

8 Ibid., p.92.

9 The German word stimmung can mean; mood, atmosphere or feeling. '“Stimmung” has several meanings, including “tuning” and “mood”. The word is the noun formed from the verb “stimmen”, which means "to harmonize, to be correct", and related to “Stimme” (voice). From: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stimmung

10 'In Greek mythology, Ananke, also spelled Anangke, Anance, or Anagke (Ancient Greek: Ἀνάγκη, from the common noun ἀνάγκη, “force, constraint, necessity”), was a primordial ancient Greek goddess of inevitability, the personification of destiny, necessity and fate.' From: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ananke_%28mythology%29

11 Ibid., p.103. Chrysothemis is speaking to Elektra.

12 Ibid., p.104.

13 On the problem of thinking extinction, see Ray Brassier, 'The Truth of Extinction' in Nihil Unbound: Enlightenment and Extinction, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007, pp.205-239.

14 Theodor Adorno, Minima Moralia: Reflections from Damaged Life, E.F.N. Jephcott (trans.), London & New York: Verso, 1974.

15 On the problem of 'ancestrality', of thinking a world prior to the emergence of thought, see Quentin Meillassoux, After Finitude: An Essay on the Necessity of Contingency, Ray Brassier ( trans.), London: Continuum, 2008, pp.1-27.

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com