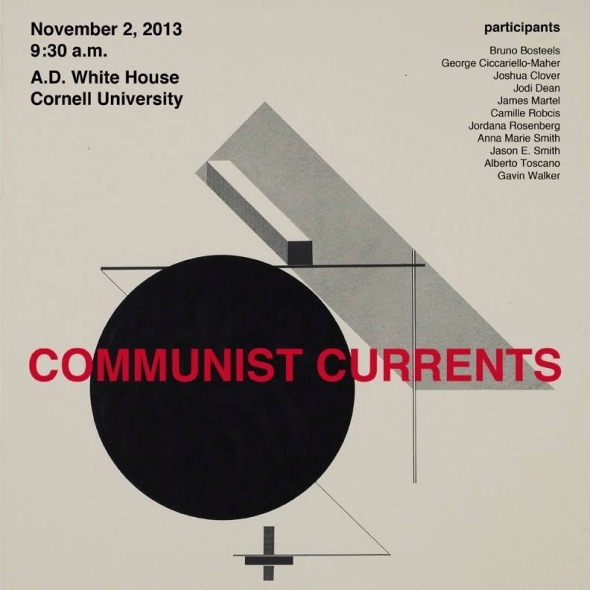

Ghost of Communism Past

A report by Ross Wolfe

After all, for the past five years conferences on the communist idea have been greeted by some as heralding the rebirth of the radical Left (“the long night of the Left is coming to a close”). Verso has released a string of titles and essay collections in its "pocket communism" series, featuring marquee names like Alain Badiou, Boris Groys, and Slavoj Žižek, as well as a host of "rising stars" — second-tier up-and-comers like Jodi Dean, Bruno Bosteels, and Alberto Toscano. After sellout conferences in London, New York, and Berlin, the organizers brought it to Seoul in South Korea, a longstanding stronghold of anti-communist reaction. Surely this bodes well for the revolution, right?

Nearly a century ago, there were those who hailed the workers' councils as the unit of proletarian organization par excellence, a vehicle for the self-emancipation of the working class. Led by figures like Anton Pannekoek and Paul Mattick, they were called "council communists." Today, it is academics' conferences that bear the promise of communism (or so it would seem). It is only fitting that they be dubbed, in like fashion, "conference communists."

For a while now, I've refrained from commenting on the event out of respect for its organizers. That respect remains undiminished, but now that some time has passed I feel like a more sober assessment of the papers presented is in order. Part of the reason I withheld criticism in the first place is that I've found my opinions often come across as needlessly "negative," even mean-spirited. Admittedly, I do find a lot of the elbow-rubbing and chummy collegiality that goes on at these academic gatherings rather tedious, if not utterly grotesque. In such moments I'm reminded of something Engels once wrote in one of his articles on The Housing Question (1872):

I am not going to quarrel with friend Mülberger [whose work Engels was criticizing] about the “tone” of my criticism. When one has been so long in the movement as I have, one develops a fairly thick skin against attacks, and therefore one easily presumes also the existence of the same in others. In order to compensate Mülberger I shall try this time to bring my “tone” into the right relation to the sensitiveness of his epidermis.

Clearly, polemic isn't what it used to be. No matter. I'll see what I can manage.

Jason Smith's paper on “Party and Form, History and Politics” was easily the best of the bunch. Honestly, even though he was arguing against uncritically adopting the old party form in light of recent struggles (think Occupy, anti-austerity protests in Greece and the indignados in Spain, the numerous uprisings during the Arab Spring), I found his talk much more historically grounded than the one that followed, in which Jodi Dean argued for a new version of the old Leninist party. Smith's perspective is largely informed by Endnotes' reworking of Théorie Communiste's thesis regarding the eroded political subjectivity of the proletariat over the course of the twentieth century, and with it the attenuation of programmatic forms of organization — whether socialist or syndicalist — that traditionally accompanied it. It's a complicated and fairly technical contention, related to "formal" versus "real" modes of subsumption under capitalism. Moreover, this seemed to be filtered through another trope that Smith has recently picked up, albeit in heavily modified form, from Alain Badiou. Namely, he borrows Badiou's characterization of the present as the "age of riots," rather than oppositional practices like strikes, which characterized the previous era of labor politics. To Smith's credit, he seeks to take seriously emerging forms of struggle, quite correct in his belief that theory (i.e., self-critical reflection on praxis) in the absence of praxis (i.e., the real transformation of the world) is devoid of content.

As I said to Smith after his talk, though he readily agreed, struggles don't always bear theoretical fruit. Fruitless forms of struggle do not necessarily lend themselves to fruitful theorization. Of course, even propitious forms of struggle can sometimes result in failure. Not all failures are fruitless, however, so it's something of a judgment call when it comes down to it. Where he sees signs of life, I see only signs of further decay.

The other talks I was far less interested in. I'd heard Bruno Bosteels present on "The Other Commune: Plotino Rhodakanaty's Mexican Pastoral" at Historical Materialism in New York, so a lot of it was pretty familiar. His point, as I understand it, was to reframe the problems posed by radical social and political experiments such as the 1871 Paris Commune by focusing on an alternative example in the New World largely overlooked by Marxist theory. (Paris 1871 occupies a fairly central place in the imagination of all subsequent Marxist thought, a favored object of rumination). Multiple layers of mediation exist in Bosteels' lecture, as he's looking at an imprisoned figure (I forget who) who wanted to write a counterfactual history along these lines. Still, this seemed to sidestep the really crucial question that the Paris Commune put on the table: the dictatorship of the proletariat. Much as they like to proclaim that they've bravely rescued the word "communism" from the purgatory of liberal indignation, conference communist philistines have of late been filled once more with wholesome terror at the words "dictatorship of the proletariat." Engels even went so far as to write in his 1891 postscript to Marx's The Civil War in France: "Do you want to know what this dictatorship looks like? Look at the Paris Commune. That was the dictatorship of the proletariat."

Not just Engels, however. There are some who like to depict Engels as a bumbling buffoon, the proverbial Watson to Marx's Holmes. Here they encounter not a little difficulty in trying to pry Marx's crystalline thought from Engels' "vulgar" additions. By Marx's own account, as he wrote in 1852 to Weydemeyer, his only "contribution was 1. to show that the existence of classes is merely bound up with certain historical phases in the development of production; 2.that the class struggle necessarily leads to the dictatorship of the proletariat; 3. that this dictatorship itself constitutes no more than a transition to the abolition of all classes and to a classless society." And it's not as if this were some naïve piece of youthful juvenilia, either. Marx reiterated this point in his 1875 Critique of the Gotha Program, in which he indicated: "Between capitalist and communist society there lies the period of the revolutionary transformation of the one into the other. Corresponding to this is also a political transition period in which the state can be nothing but the revolutionary dictatorship of the proletariat."

Talk of the "transition" between capitalist and communist society would seem a natural lead-in to Alberto Toscano's paper on "Transition Deprogrammed," on the issue of the dictatorship of the proletariat. Apart from the spirited exchange between Trotsky and Kautsky during the Russian Revolution, in which they traded metaphors about horses and engines to allege Russia's (un)readiness to lead a proletarian revolution, Toscano's dry rereading of a few moth-eaten texts by Étienne Balibar from the 1970s on transition was otherwise a snoozer. How he got there from Trotsky-Kautsky I'll never know; he must've just leapt right in. You could almost feel the exegetical fatigue humming through the microphone. Similarly, I strain to remember anything from James Martel's presentation "What is Common," except for the fact it was a hyperbolically close reading of just three words (!!!) from a single sentence (!!) in Jodi Dean's The Communist Horizon (!!!!). I seem to recall that he endorsed her idea of "the commons" as a fragmentary unity, composed of diverse and often antagonistic group interests. The enthusiasm for Negri's resuscitated notion of "the commons" is somewhat beyond me; it seems a subtle form of nostalgia for precapitalist times, really, before enclosure and primitive accumulation ruined everything. Engels explicitly warned against such conservative sentimentality in Anti-Dühring:

All civilized peoples [i.e., all those who arrived at settled agriculture] begin with the common ownership of the land. With all peoples who have passed a certain primitive stage, this common ownership becomes in the course of the development of agriculture a fetter on production. It is abolished, negated, and after a longer or shorter series of intermediate stages is transformed into private property. But at a higher stage of agricultural development, brought about by private property in land itself, private property conversely becomes a fetter on production, as is the case today both with small and large landownership. The demand that it, too, should be negated, that it should once again be transformed into common property, necessarily arises. But this demand does not mean the restoration of the aboriginal common ownership, but the institution of a far higher and more developed form of possession in common which, far from being a hindrance to production, on the contrary for the first time will free production from all fetters and enable it to make full use of modern chemical discoveries and mechanical inventions.

Unexpectedly, the paper I expected to hate the most turned out to be much better than I'd anticipated. Jordana Rosenberg, the woman who presented on "The Molecularization of Sexuality: Capital Accumulation and the Ontological Turn” had a couple things the other panelists lacked: stage presence, and an uncanny sense of timing. Her delivery made some of the frankly excruciating jargon far more bearable. Plus, it became clear in the course of her exposition that many of the terms included in the title of her talk were precisely those that she meant to criticize. Though her own commentary was also sometimes a bit stilted and clunky, some of the confusion was probably unavoidable, as it was encoded in the texts and positions Rosenberg critiqued. Besides, I sympathized with her disdain for object-oriented ontology, that miserable neue Sachlichkeit of philosophy. The poet and sometimes political economist Joshua Clover raised a decent objection to her narrative, however: Wasn't Rosenberg rather hasty in borrowing David Harvey's notion of neoliberalism and ongoing primitive accumulation? (As opposed to the "one and done" model, whereby it only happens once, in which capitalism doesn't have to constantly create a new "periphery" from which to extract value, as if anything today exists "outside" the globality of capitalist relations).

Lately, I've begun to wonder what the significance of this renewed interest in "communism" actually is. Is it a fad? Just an "edgy" marketing scheme? Or does it have anything like real political purchase? So far it's a mainly academic phenomenon, though Libcom forums have managed to popularize the phrase "full communism" and though Sebastian Budgen continues to promote it through the "counter-hegemonic apparatus" of his small publishing empire. Who knows what it might lead to?

Today, however, something blipped across my radar — okay, my Facebook feed — that should've thrown up red flags (pun intended) for everyone all around. George Ciccariello-Maher, author of We Created Chavez: A People's History of the Bolivarian Revolution and a seasoned conference communist, publicly inquired:

I had always assumed The Communist Manifesto played a major role in marking the workers' movement as "communist" (especially since the Paris "commune" didn't come until 1871). But this doesn't account for the pre-existing "specter of communism." — Any idea what or who Marx and Engels were referring to? Who, besides "Pope and Tsar, Metternich and Guizot, French Radicals and German police-spies," was decrying communism and why? (An abiding interest in how imposed identities are reappropriated).

Marx and Engels were, needless to say, hardly the first "communists." This much should be obvious from the Manifesto itself, whose third section includes a lengthy critical review of the "existing socialist and communist literature." Not to mention the incredibly famous letter from Marx to Ruge, in which the former calls for the "ruthless critique" of all that exists." He also mentions, not long thereafter, the communism of "Cabet, Dézamy, and Weitling."

I'm flabbergasted by how few of the conference communists know this. This is intro-level stuff, really, schoolboy fodder for most leftists worth their salt. When I pointed this out, someone sarcastically remarked: "Yes, everyone who isn't born with a knowledge of the history of the communist movement prior to Marx should just hang their heads in shame." Of course, it's not at all a matter of being "born with it." You'd think that if you're being featured as a panelist at academic conferences on "communism," there'd be an assumed level of knowledge in the field. This isn't even something anyone would need to read a detailed history of, let alone a biography of x, y, or z pre-Marxian communist. Just by reading Marx, this much should be clear.

"Communist Currents" was a mixed bag, unevenly developed. But for the most part, aside from the papers by Smith and Rosenberg, it was nothing more than lack of insight buried under mounds of useless erudition. With this last bit, one begins to wonder if all the emphasis on "communism" or "the communist idea" (both rather empty signifiers) doesn't serve to conceal the still more looming specter of Marxism. "Communism" can be just as obfuscatory as any other political ideology. As Marx wrote:

Communism is for us not a state of affairs which is to be established, an ideal to which reality [will] have to adjust itself. We call communism the real movement which abolishes the present state of things.

This may serve as a coda for the preceding.

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com