Practice Makes a Master

If images of (certain) women are everywhere, lubricating the sale of product, they are also nowhere when it comes to picturing their acts of heroism or banality. Croatian artist Sanja Iveković has spent years exploring the gap between female invisibility and appearance – review by Nick Gledhill

Following a major retrospective of Sanja Iveković's work at MoMA in 2011, Unknown Heroine offers another chance for a relatively unfamiliar Anglophone audience to acquaint themselves with one of former Yugoslavia's most influential contemporary artists. A feminist activist and pioneer in video and performance art, Iveković's roots are in the highly politicised Nova Umjetnička Praska (New Art Practice) movement that emerged in Belgrade and Zagreb after 1968. Based continuously in what is now Croatia, Iveković's career has been heavily inflected by the region's political and social volatility, and this collection, spread across two London galleries, brings together her major works spanning four decades and tackles issues of female identity, consumerism, violence and political amnesia.

The backdrop for artists working in post-war Yugoslavia was the unique environment of Josip Tito's Socialist Federal Republic which, while nominally socialist, offered its citizens both access to a western-style market in consumer goods and freedoms of speech, travel and political engagement that were unparalleled anywhere behind the fabled 'iron curtain'. Unconfined by creative limitations to state-sanctioned realism, generations of Yugoslav artists engaged in a social critique and formal experimentation that would have seemed more at home in the studios of Paris and New York than anywhere else within the Soviet bloc. Groups like EXAT 51 and the antiart collective Gorgona, active throughout the 1950s and ’60s, began a critical examination of social policies and the conventions of art that mirrored the practice of more familiar (to westerners) avant-garde groups like Fluxus and the Situationist International. As a part of this tradition, the New Art Practice sought specifically to democratise art by taking it out of galleries and onto the streets, favouring the use of cheap, easily attainable materials and fleeting, politically charged performances.

Entering this vibrant and experimental scene in the early 1970s Iveković was confronted with a situation where, despite much revolutionary posturing and egalitarian rhetoric, traditional gender roles remained largely unchallenged. This was true both on a national level — where the official line ran that a feminist stance was 'superfluous in [a] society that had already overcome gender differences in the Revolution'i — and also in an art scene dominated mostly by men. Hence Iveković's early projects lay out a confrontational feminist agenda, preparing the ground for the questioning of hegemonic gender codification and rituals of identity-formation that would comprise one of the main themes running continually throughout her work.

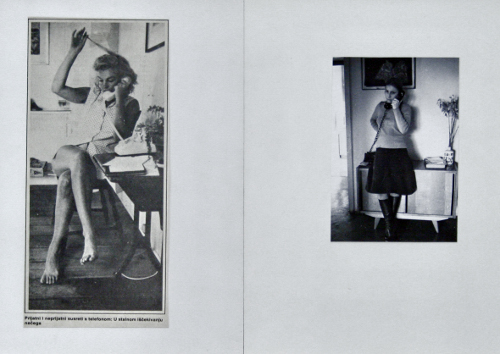

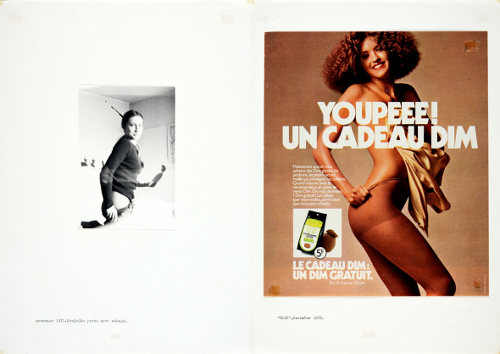

Image: Sanja Iveković, from the series Tragedy of a Venus, 1975-76, photomontage

Pieces such as Tragedy of a Venus (1975-6) Sweet Life (1975-6) and Double Life (1975) are examples of this early work and consist of series of photomontages juxtaposing images taken from the mass media with photographs from the artist's personal albums. Through this technique, Iveković was in part focussing a critical lens on representations of the so-called 'new Yugoslavian woman' — a curious amalgam of utopian socialist ideology and capitalist aesthetics propagated by a regime promoting a prescribed national image of femininity based around Yugoslav 'beauty joy and diversity' as opposed to what it termed the 'drably dressed' women of Russia.ii Unlike their counterparts in the Soviet Union, Yugoslavian women were permitted — or rather tacitly encouraged — to follow western fashion and lifestyle trends, and Iveković's early work testifies to the intrinsic paradoxes of a system ostensibly based on Marxist/Leninist values that nonetheless remained deeply patriarchal, perpetuating a stereotype of women as passive objects of beauty and domesticity.

In Double Life, images of women used to advertise clothes, beauty products and various 'feminine' consumer goods are taken from magazines of mixed Yugoslav and Western origin, such as Elle, Grazia, Duga, Svijet and Marie Claire, and paired with snapshots from various periods of Iveković's own life between 1953 and 1975. The pairs of images are aligned through similarities of gesture, pose and setting, but since each of her private images pre-dates the corresponding public one it is clear that Iveković is not simply re-enacting the advertisements. Rather, she is hinting at the idea of a perpetual cultural construction of the female subject so deeply embedded that it interpellates the individual in a way that can be both unconscious and retroactive. In this sense, Iveković's work from this period pre-empts Judith Butler's thesis on gender identity as culturally constructed through the repetition of stylised acts in time, and Iveković is elucidating the performative nature of her own femininity.

The pairing of images suggests that as a woman — and also an adolescent and even a little girl — her actions were always-already subject to a kind of Foucauldian 'regulative discourse', an unconscious exhortation to construct an identity parallel to that which is constantly reproduced in the propaganda of patriarchy and consumerism. In each photograph the young Iveković unknowingly both mirrors and foreshadows the media image, her own identity revealed as being just as unstable and contingent as that of the anonymous model with whom she is juxtaposed. In this way, Iveković draws our attention to the power of mass media in identity construction and the essentially recondite and ephemeral status of 'true' identity, while also analysing her own political situation in a society that, despite being one of the most successful examples of the historically elusive 'really existing' socialism, was also one in which feminist discourses were marginalised and where, in the artist's own words, 'the consumerist dream was a part of everyday life.'iii

Image: Sanja Iveković, from the series Double Life, 1975, photomontage

The conceptual twist in this piece — that the pictures of the artist pre-empt rather than re-enact the reclaimed magazine images — is original, but nonetheless to a 21st Century eye photomontages such as Double Life and a number of the other early pieces that make up much of the exhibition can't help but come across as dated. They would have no doubt been striking and provocative in the Yugoslavia of the 1970s, but they are less so in a late-capitalist supermodernity where notions of both the cultural construction of gender identity and disappearance of the world into representation have been explored extensively by so many high profile artists over the intervening decades (Cindy Sherman and Tracey Emin spring to mind immediately) and where uses of these kinds of materials and techniques have become so run of the mill that, taken completely out of context, Double Life evokes more the end of year show of an art foundation course than the output of a highly respected doyenne of the European new avant-garde.

This is a shame, as there is a risk that the uninformed viewer may form an impression that fails to do justice to the scale, diversity and historical resonance of Iveković's work. This is particularly true of the section in South London Gallery, which seems to be serving as a kind of overspill from the far more thoughtfully curated Calvert 22 and doesn't stand up well on its own. In fact, an unsympathetic visitor might be tempted to suggest that the curator has been overly ambitious in attempting a retrospective of this scale in such a limited space. But nonetheless the show is long overdue, and Lina Džuverović has done well to bring Iveković to London for her first solo show in the UK.

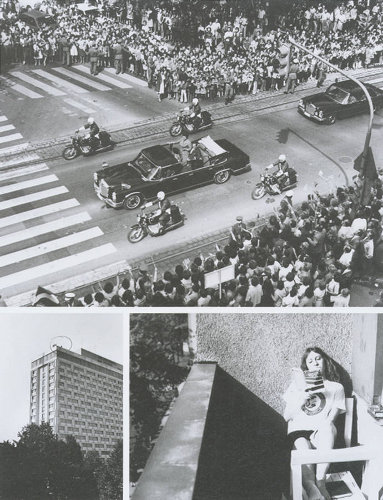

To be fair, many of the artist's most important works simply defy capture in the context of a conventional gallery space, as was after all the spirit of the New Art Practice. Among Iveković's most famous and influential performances for example, is the completely irreproducible Triangle (1979), which consisted of the artist reclining on her balcony in Zagreb, drinking whiskey, reading a book and simulating masturbation as President Tito's motorcade passed by in the street below. Knowing that she would be observed by a secret service man stationed on a roof nearby who would then call a policeman to come and order her inside (citizens were forbidden from being on their balconies as the motorcade passed), the performance was intended to provoke what the artist saw as 'an intercommunication between three persons'. This provocation of authority manifested via the male gaze, coupled with the blurring of boundaries between public, private, personal and political, all set against the oppressive presence of the absurdly masculine personality cult of the leader, comprised a highly nuanced performance piece of great inventiveness and conceptual weight. It is a pity that all we have as documentation of it are four black and white inkjet-printed photographs and a short text, but awareness of such actions goes a long way to contextualising all the other pieces on offer and deepening our interest in Iveković.

Image: Sanja Iveković, Triangle, Zagreb, 1979

Similarly (and understandably) absent from the exhibition is the artist's most ambitious work to date, the controversial public sculpture Lady Rosa of Luxembourg (2001). Although barely known in Britain, this work was the topic of fierce national debates, public forums and news coverage across the Benelux states, Germany and France in the first few years of the millennium. Iveković recreated the Gëlle Fra (Golden Lady), a larger than life, gilded neoclassical statue of the goddess Nike set on top of a 69 foot obelisk which serves as Luxembourg's most revered national war memorial. In an audacious détournement, Iveković's full-scale replica featured three critical interventions. The goddess is now heavily pregnant and the text around the base — which in the original features the names of fallen (male) Luxembourgian soldiers from the two world wars — is replaced instead with the French, German and English words: LA RÉSISTANCE, LA JUSTICE, LA LIBERTÉ, L'INDÉPENDENCE — KITSCH, KULTUR, KAPITAL, KUNST — WHORE, BITCH, MADONNA, VIRGIN. Finally, rather than the country, the new monument is instead dedicated to the martyred revolutionary activist Rosa Luxembourg.

This replica, erected within walking distance of the original, draws attention to how an official, patriarchal version of history erases the presence of women through the imposition of a symbolic order that constantly denies them agency. The role of women in Luxembourg's resistance to Nazism in World War II for example, has been all but removed from popular historical discourse through an endemic phallocentricism that recognises only male heroism and permits representation of the female solely in the form of idealised, allegorical symbols of national identity (the 'Golden Lady' of Luxembourg, 'Marianne' of the French Republic, 'Britannia', etc.) in what amounts to an incessant confirmation of the still unreconstructed 'false aura' of mystery and otherness conferred on women by patriarchy that de Beauvoir outlined in The Second Sex. The pregnancy (both literal and idiomatic) of Iveković's statue stands as a testament to the very real, physical and vital presence of women in all of the historical social struggles that monuments like the Gëlle Fra are supposed to commemorate.

And this of course is the central idea that lends the show its title, Unknown Heroine, and comprises the main political statement behind it. In the 21st century Iveković has partly shifted her focus; from the cultural construction of her own identity as a woman to a wider examination of history and society centred around a conceptual synthesis of anonymity/femininity. This is achieved primarily through a forensic pursuit of actual lost heroines from history, such as in Invisible Women of Solidarity: 6 out of 5 Million (2009-10), which comprises six screen prints appearing at first glance to be blank, but where, in a kind of trompe l'oeil, the 'invisible' portraits of six women come into ghostly resolution when viewed from certain angles. These are leading members of the Polish workers union Solidarnos (Solidarity), who opposed and eventually ousted the Soviet-backed communist regime in the 1980s. Largely omitted from the official history of the union, the faces of these six women serve to remind us of the 5 million female members of Solidarity who contributed to the Polish struggle for independence.

Image: Sanja Iveković, Lady Rosa of Luxembourg, 2001

Iveković's use of specific historical events and individual lives to draw attention to the marginalisation and betrayal of the feminine is highly effective, and gains considerable poignancy through the personal connections that the artist herself often has to them. Probably the most affecting piece in the exhibition is Searching For My Mother's Number (2002), a three screen video installation accompanied by files of various research material documenting Iveković's attempts to uncover missing information about her mother, Nera Šafarič, who was a partisan in Nazi-occupied Yugoslavia and inmate of Auschwitz. Adding to the resonance of this piece is its positioning (in Calvert 22) opposite Gen XX (1997-2001), a set of prints showing images of models which, in a partial reinstatement of her earlier techniques, Iveković has taken from fashion magazines and détourned. This time the advertising copy accompanying each image has been replaced with a text documenting the fates of six young female anti-fascist militants (including the artist's mother) who were imprisoned, tortured or executed in Yugoslavia during World War II. Originally these were then re-published by Iveković in the independent magazine Arkzin, in an effort to engage a younger audience with examples of female courage and sacrifice within a context typically associated, in the collective historical consciousness, with machismo. This is just one example of the active social and political engagement that runs concurrently with Iveković's artistic production, a vestige perhaps of the rare political environment from which she emerged. As the artist herself commented recently, 'the important advantage of living and working within socialism is that you learn very early on that nothing is free from ideology, everything we do has a political charge and the division between politics and aesthetics is entirely erroneous. I think my work reflects that.'iv

And so, overall, Iveković confronts us with a jarring reminder of an ongoing and incomplete historical struggle for equality and recognition, a reminder made all the more pressing by the increasingly precarious status of that struggle in a present mortally threatened by the total submersion of culture in the suffocating dross of late capitalism. This is a timely, forceful and positive artistic intervention from a woman whose generation still believed that real change was possible, who were themselves witnesses to the irresistible rise and ignominious fall of successive ideological behemoths, and who beheld the actual fragility of apparently invulnerable symbolic orders of the past. The overall effect is empowering rather than despondent, emphatic rather than cynical, and presents us with a refreshing departure from the self-reflexive irony and political nihilism usually dominant in conceptual art's contemporary milieu.

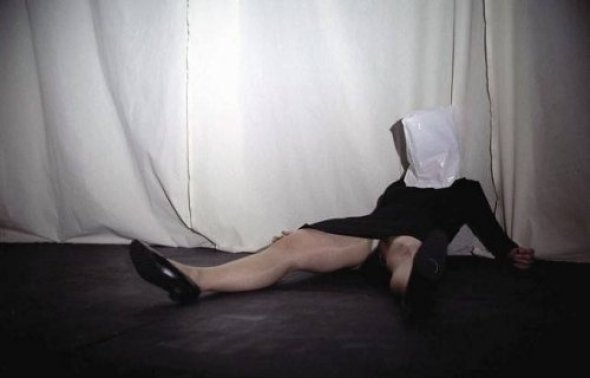

I personally will retain above all the experience of viewing, in one claustrophobic, isolated room of Calvert 22, the 2009 re-enactment by the dancer Sonja Pregrad of Iveković's 1982 video performance Practice Makes a Master. This is a haunting piece in which an anonymous hooded woman repeatedly struggles to her feet and is then seemingly shot down by an unseen assailant, sprawling theatrically on the floor before rising again and then falling again, accompanied by an incongruous, disturbing audio mix of gambling machine jingles and Marilyn Monroe movie soundtracks. In what is just one of several examples of Iveković's eerie historical prescience, the work is powerfully evocative of — and yet predates by many years — both the violent tragedy of the Balkan Wars of the 1990s and the extra-judicial hells of Abu Ghraib and Guantanamo Bay, with their own hooded victims. She stands and is shot down, she stands again and is shot down again, relentlessly annihilated by the unmitigated barbarism of a faceless, immanent and apparently incontestable power, yet she always gets back on her feet, the performance endures. Even though the situation looks hopeless, nonetheless the struggle goes on. To stop fighting is to stop living.

Nicholas Gledhill <negledhill AT hotmail.com> is a London-based writer and graduate of the Centre for Cultural Studies, Goldsmiths

Info

Sanja Iveković - Unknown Heroine, Calvert 22 and South London Gallery, 14 December 2012 – 24 February 2013. Curated by Lina Džuverović

Footnotes

iBojana Peji, 'The Morning After: Plavi Radion, Abstract Art and Bananas', n.paradoxa 10 (2002) pp.75-84; quoted in Roxana Marcoci, Sanja Iveković: Sweet Violence, New York: MoMA, 2011, p.20.

ii From a speech by Yugoslav politician Vida Tomši at the Communist Party session of October 10, 1948, quoted in Bojanna Peji, (ed.), Gender Check: Femininity and Masculinity in the Art of Eastern Europe, Cologne: Walter Kӧnig, 2009, p.97.

iiiSanja Ivekovi, quoted in Sanja Ivekovi: Unknown Heroine, Exhibition Guide, London: Calvert 22, 2012.

iv Sanja Ivekovi, from an interview with Dazed Digital, December 2012, http://www.dazeddigital.com/photography/article/15...

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com