SPECIAL PROJECT: Fear Death by Water (The Regeneration Siege in Central Hackney)

The London Particular (Benedict Seymour and David Panos) see the borough of Hackney in the East End of London as a microcosm of contemporary power processes. Long a dumping ground for London’s poor, Hackney is becoming an increasingly regulated space of flows, where, in the name of life and culture, ‘regeneration’ incubates gentrification and new forms of biopolitical control. Taking the recent police siege in Hackney’s ‘creative quarter’ as the key to an increasingly precarious urban condition, this special project looks at the possibilities for life in the regenerated inner city

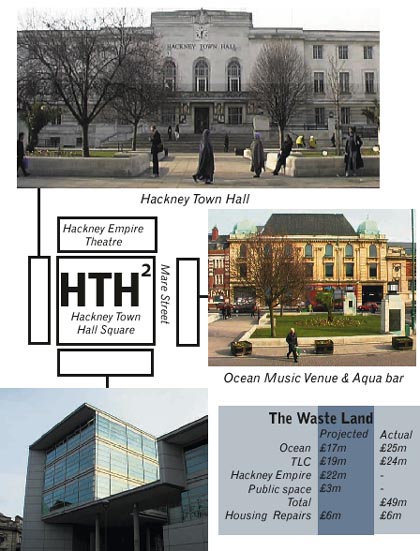

The Hackney Creative Quarter

Welcome to HTH2, formerly Hackney Town Hall Square. A £70 million-plus project for the cultural renewal of central Hackney in London’s east end, HTH2 is the heart of the area’s new ‘creative quarter’.

Home of artists and immigrants, Hackney is a traditionally working class area undergoing protracted gentrification. The nomination and production of a creative (aka cultural) quarter is intended to act as a regeneration incubator, attracting a new class of customer to this formerly despised part of the capital. HTH2 combines a music venue (The Ocean Centre), a library and new media complex (The Technology & Learning Centre or TLC), rehabilitated public space (the square itself) and theatre, comedy and other live arts (the refurbished Hackney Empire). The whole project was funded through a private finance consortium including MACE, Roche, Tarmac Constructions and Schroder’s Bank.

The Ocean, with its concert halls, production facilities and Aqua bar, enjoys a 150-years rent-free lease from Hackney Council plus a £300,000 a year grant. The council, declared bankrupt in 2001, recently auctioned off a large share of its housing, nurseries, doctors surgeries, playing fields, schools, youth clubs, libraries and swimming pools. Prices were very competitive and developers picked up bargains in an area which has seen London’s steepest increase in property values. Hackney Council continues to cut back on services and staff but has no long term means to remedy its structural under-funding at the hands of central government.

With a remit to deliver ‘vibrancy’ to the square and its environs, HTH2 displays all the stigmata of regenerated space. Aseptic, generic and surveilled, it’s a vitrification of place (something socially produced and by definition volatile) into planned ‘ambience’. Silting up the channel between the area’s past and future, the square places heritage (the TLC now hosts Hackney Museum) next to learning and culture, domesticating them all.

The square is not the only part of Hackney’s regeneration programme, however...

The Hackney Siege

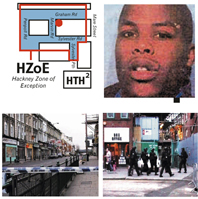

The Hackney Siege was a £1 million pound project for the spatial sterilisation of the area adjacent to the Town Hall Square. Lasting 15 days, it deployed squads of paramilitary police round the clock and shut down several streets and a major road. 43 Hackney residents were trapped inside their homes, some without television, from Boxing Day 2002 until well after twelfth night. A further 200 residents were compulsorily displaced on the order of the authorities during the course of the project.

More than just a conventional siege, this was a pioneering partnership between police and residents which transformed a state of emergency into a new model for everyday life in the city. The Hackney Zone of Exception (HZoE) was also a good example of what regeneration professionals call ‘people-lead regeneration’. At its heart lay the police’s preemptive ambush of a local man, the so-called ‘yardie gangster’, Eli Hall (29). Suspected of possessing illegal firearms, Hall was pursued by an Armed Response Unit whose response efficiently anticipated any action on the suspect’s part. After taking shelter in his bedsit on Marvin Street, Mr Hall and his hostage were successfully contained within the house while the police rationalised his services. After a few days without heating, electricity or light, the hostage fled and the tenant set fire to his own home in a desperate effort to warm the place up.

More than just a conventional siege, this was a pioneering partnership between police and residents which transformed a state of emergency into a new model for everyday life in the city. The Hackney Zone of Exception (HZoE) was also a good example of what regeneration professionals call ‘people-lead regeneration’. At its heart lay the police’s preemptive ambush of a local man, the so-called ‘yardie gangster’, Eli Hall (29). Suspected of possessing illegal firearms, Hall was pursued by an Armed Response Unit whose response efficiently anticipated any action on the suspect’s part. After taking shelter in his bedsit on Marvin Street, Mr Hall and his hostage were successfully contained within the house while the police rationalised his services. After a few days without heating, electricity or light, the hostage fled and the tenant set fire to his own home in a desperate effort to warm the place up.

Drenched by police water jets and worn out by the protracted process of consultation, Mr Hall was wounded in the mouth by a police bullet and later, it is alleged, shot himself in the head. Having declined the munificence of the state and obstructed attempts at dialogue, his lifeless body was removed from his home.

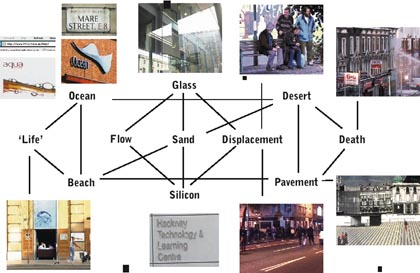

Liquid Regeneration, Social Desertification

The Town Hall square’s new amenities riff on the idea of revitalisation by water and fluidity. The Ocean music venue has an educational facility called Rising Tide and a bar called Aqua; The Technology & Learning Centre’s internet terminals give local people (of fixed abode) a chance to surf in the space of flows, and the HTH2 online forum about developments in the square was created by a trans-disciplinary network called F-L-U-I-D.

Picking up on the latent seaside connotations, the architects Gross Max have proposed a boardwalk-style ‘special pavement’ for the square, an effort to bring an ambience of play and sociability to this stony slab of municipal space. But if the ‘urban beach’ semiotics don’t convince then the TLC’s glass facade and networked heart at least embody the centrality of sand to the whole package. Silicon implants are intended to turn the frumpy old square into a nexus where desiccated flows intersect.

Beyond the cloying hydraulic rhetoric, the real effect of this flood of culture is a creeping desertification. The official sites of education and entertainment that promise to compensate for gentrification actually contribute to the social cleansing of the area. Flushing out undesirable elements, from the homeless to the hooded youth, the square’s well-policed makeover begins with the economic, semiotic and physical dissuasion of the poor and ends by sucking in a flood of new consumers better able to afford and enjoy the rehabilitated space.

The Hackney Zone of Exception continued the square’s fixation on fluidity, materialising the metaphor with displacements of its own. The HZoE ‘decanted’ the inhabitants of this promising residential area for a 15-day trial period and helped move key siege stakeholder Eli Hall to ‘a better place.’ As council housing stock is privatised or demolished many other local people, in particular elderly tenants, have already been definitively relocated.

The siege was not just about moving people out of the area, though. Complementing the spatial sterilisation of the square already achieved by the PFI projects, the siege’s police cordon delivered instant crime reduction through ‘total restriction’. The ability to suspend local citizens’ right to freedom of movement for an indefinite period renders all criminals, both potential and actual, equally immobile. No more flow for them.

While the HZoE was only a pilot, plans to apply the same ‘urban quarantine’ approach on a city-wide scale are already well under way. As part of the wider regeneration project known as The War on Terror, the government is planning to introduce total urban lockdown, with whole cities sealed off in the (non)event of a possible terror threat. The liquefaction of urbanism paradoxically coincides with the attempt to place entire cities under arrest.

Today it is not the city but rather the camp that is the fundamental biopolitical paradigm of the west. [This] throws a sinister light on the models by which social sciences, sociology, urban studies, and architecture today are trying to conceive and organize the public space of the world’s cities without any clear awareness that at their very centre lies the same bare life (even if it has been transformed and rendered apparently more human) that defined the biopolitics of the great totalitarian states of the twentieth century.

– Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life, Giorgio Agamben

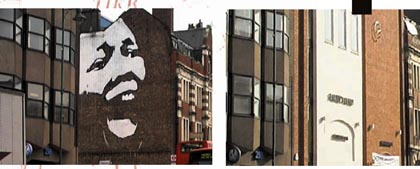

>> Next to the Ocean music venue, a new Wetherspoons 'pub' has erased a public artwork from an earlier era of community-regeneration

GESAMTKUNSTWERK

... the integration of artwork helps to make Hackney town square something special. At present a visual artist, composer and light artist are collaborating with the architects to make the square into a special experience of all the senses. Light, texture, sound and, if budget allows, specially designed water jets and mist machines may create a unique atmosphere to be enjoyed by all. – Gross Max Architects

We liked the idea of doing almost nothing, creating more of an open invitation rather than a prescribed script... nearly invisible, nearly inaudible. – Alan Johnson & Max Rolgasky, Artists

Contemporary regeneration means ‘doing almost nothing’ with almost no cash: over £70million for a flagship cluster of cultural ‘capital projects’, £1 million on a state of the art siege, but only £6 million for the repair of social housing. The council subsidise the Ocean centre in perpetuity but does not extend the same largesse to their human tenants.

If we used to be ‘voluntary prisoners of architecture’ (Koolhaas), trapped in the grid of functionalist urbanism, today we are the involuntary prisoners of situationism. After the top-down prescriptions of modern planning, macroscopic and instrumental, this is a molecular and affective urbanism of infinite sensitivity. Regenerated space wants to preempt your emotions and aspirations, conform itself to your desires. At its best it is a siege on the subject, an anticipatory retaliation against your capacity to dream. Regeneration is ‘holistic’, it is ‘bottom up’, it is ‘about people’, all the old situationist virtues – minus the disruptive necessity of extricating of our desires from the apparatus of profit.

While regeneration concentrates on cheesily impersonating the finer things - mosaics and lavender lighting, interactive musical pavements - more humble desires are neglected. After the major surgery of functionalist urbanism – council housing, ring roads, schools, etc - this is a new regime of urban acupuncture: rechanneling intangible flows, adjusting the social chakras, a micropolitics of soft control.

While regeneration concentrates on cheesily impersonating the finer things - mosaics and lavender lighting, interactive musical pavements - more humble desires are neglected. After the major surgery of functionalist urbanism – council housing, ring roads, schools, etc - this is a new regime of urban acupuncture: rechanneling intangible flows, adjusting the social chakras, a micropolitics of soft control.

Scrupulously reversing the old ‘mistake’, regeneration creates its negative image to suit the unprecedented miserliness of contemporary capitalism. The turn to emotion and inclusivity masks a turn away from building new homes and infrastructure. Not that music and books aren’t essential, but for every showpiece TLC opened,10 existing libraries are shut down.

Aside from the big fiascoes, the culture palaces that tend to self-destruct, the swimming pools too expensive for the majority to use, regeneration is a programme of subtraction: the systematic destruction of collective resources, privatisation of services and evacuation of social space.

He do the police in different voices

The Town Hall square is also the virtual network of consultation forums in which the physical space is cradled, by which it is preceded and post-mortemised.

In today’s regeneration, participation and engagement are compulsory. ‘Apathy’ is not an option. The permanent and ever-proliferating condition of consultation defers the encounter with social conflict and economic inertia. Endless consultation may consume most of the cash or permanently postpone its expenditure, but perhaps this is the point. More importantly for the network of agencies that constitute the micropolitical ‘Regeneration State’, consultation devolves responsibility – not power – onto the patients of the regime. Whatever regeneration does, it must be legitimate because they asked you for your input at every stage. If you don’t like the end results you only have yourself to blame. Then again, when the preferred outcome prestructures the options, the propaganda is deceitful, and even majority decisions – if unfavourable to the government’s core agenda – are repeatedly ignored, people’s disengagement from the frenzy of dialogue is not only understandable, it may be politically essential.

In today’s regeneration, participation and engagement are compulsory. ‘Apathy’ is not an option. The permanent and ever-proliferating condition of consultation defers the encounter with social conflict and economic inertia. Endless consultation may consume most of the cash or permanently postpone its expenditure, but perhaps this is the point. More importantly for the network of agencies that constitute the micropolitical ‘Regeneration State’, consultation devolves responsibility – not power – onto the patients of the regime. Whatever regeneration does, it must be legitimate because they asked you for your input at every stage. If you don’t like the end results you only have yourself to blame. Then again, when the preferred outcome prestructures the options, the propaganda is deceitful, and even majority decisions – if unfavourable to the government’s core agenda – are repeatedly ignored, people’s disengagement from the frenzy of dialogue is not only understandable, it may be politically essential.

If you take the comments on the online forums seriously, what ‘the people’ actually want is not sentient street furniture and emotional lamp posts but shelter: ‘new houses for everyone and safe places for little ones’; repairs to their homes and estates; a host of selfish and functionalist concerns. It’s as if they’d never heard of the situationists.

Like the ‘dialogue’ which the police successfully prosecuted with Eli Hall during the siege-consultation, the apogee of the regeneration forum is the séance. The HTH2 online forum is a safely contained postfestum complaint session without actual performative force. Desire is solicited then conspicuously displayed on screen in order that it be displaced. Speech is stimulated to dissimulate the imposition of policy on the people. ‘Giving the community a voice’ results in a deathly civic silence.

HURRY UP PLEASE, IT’S TIME

Aesthetically avant garde, cultural regeneration goes one better than the current fashion for artistic reenactments. In summer 2002 the siege was pre-enacted in the Town Hall square when police cordoned off the area after a public occupation of the town hall. Soon after the Ocean opened, the Samuel Pepys pub opposite was shut down. On the Pepys’ last night, 300 of the pub’s clientele spilled out into the square. After some of the revellers broke into the town hall in protest against the pub’s closure, the police came in to mop things up.

Like a collective rehearsal for the HZoE’s open plan imprisonment of the area’s occupants, the Pepys posse were surrounded by a fleet of cop vans, the town hall besieged and the street sealed off. This was not what participative democracy is supposed to look like. The police outdid the Italian caribinieri in their brutal response to this unsolicited display of local desires.

Spatial reform sometimes requires the direct use of force. The new order violently imposes itself on the partisans of the old. The closure of the Pepys, haunt of local musicians, crustie anarchists, miscellaneous drinkers and other ‘Anti-Social Behaviour Orders’ (ASBOs) waiting to happen, marked the end of an era. No more free music, no more late night lock ins. From Ocean on you have to pay, doors close 11.30pm.

Spatial reform sometimes requires the direct use of force. The new order violently imposes itself on the partisans of the old. The closure of the Pepys, haunt of local musicians, crustie anarchists, miscellaneous drinkers and other ‘Anti-Social Behaviour Orders’ (ASBOs) waiting to happen, marked the end of an era. No more free music, no more late night lock ins. From Ocean on you have to pay, doors close 11.30pm.

The Ocean sucks dance culture into the belly of the regeneration state. Bringing a source of semi-independent cultural production into a new physical proximity to the town hall, it attempts to integrate elements of the local scene. A sop to the ‘ethnic minorities’ and black club promoters, the Ocean allows greater control of a potentially disruptive culture. Meanwhile, with the demise the Pepys, another organically occurring cultural scene is forced out.

SACRED LIFE

Such tactics are expensive – the Hackney siege has so far cost around £500,000 – but the priority is to preserve life’ – Metropolitan Police

The ‘sacredness of life’ is the fundamental axiom of contemporary policing and contemporary regeneration alike. Eli Hall’s police consultation partners had his and the community’s best interests at heart when they cut off the electricity and gas to his temporary accommodation and turned the water jets on him. The same solicitude motivated the government when it cut off funds to the bankrupt Hackney Council and imposed austerity on the people of the borough.

Culture in all its forms is fundamental to our health and development as individuals and as a society – Hackney Cultural Strategy

The sacredness of life is an injunction to prolong biological existence insofar as it is productive of profit. The north and south of the square represent the two extremes of the biopolitical continuum this implies. The TLC is biopower’s deluxe wing, Eli’s deathpad it’s servant’s exit. The TLC’s ontologically correct fusion of body (gym) and spirit (internet) mirrors the cops’ fusion of dialogue and deadly force. Moralising the flesh and physically incarnating the law, the Paragon gym (‘turning virtues into reality’) serves the cult of bodily effectiveness (korperkultur). The disabled are welcome, of course, that’s why the council abolished their free transport.

You’ll never take me alive – Eli Hall

On one side of the square the law is ‘live life to the full’, net-surfing and nautilus machines, on the other life is living law (lex animata): The police now incarnate the law in their proper persons and directly exercise their sovereign decision over the patient’s (dead) body with their ensemble of guns, megaphones and waterjets. True to regeneration’s ‘devolved’, ‘bottom-up’ management, the authorities can proudly point out that Mr Hall was, of course, the architect of his own demise. That’s what self-administration is all about.

HOBO ASBO BOHO

Artists have a transportable infrastructure... They are a natural first group to come into an area which will then seed the bars and other support systems for the creative industries

– Fred Manson , regeneration guru

One of the few remaining homeless in the Town Hall Square is the ‘mobile man’, an elderly gentleman with his own transportable infrastructure. With his survivalist hoard - gas ring, tea flask and carefully organised Tesco bag system - mobile man has become entirely ‘responsible’ for himself, a model of self-management.

As such he is the prototype for the majority of Hackney’s erstwhile citizens. Stripped of homes, rights, and resources, the less affluent exist with the permanent possibility of demotion to refugee status. As welfare support is terminated leaving only the hypertrophied police-culture function of the state, individuals are thrown back on their own improvised resources.

Like Baudelaire’s Parisian ragpicker, mobile man is also the prototype of the artist in the regeneration state. Obsessed with the debris of collapsing systems of taste, today’s bohème rehearses a preemptive impression of proletarianisation (‘white trash’) as a means of upward social mobility. Per cacus ad astra. The few become stars, the majority will be forced out of this new creative zone as they were previously forced out of nearby, now-gentrified, Shoreditch.

Like Baudelaire’s Parisian ragpicker, mobile man is also the prototype of the artist in the regeneration state. Obsessed with the debris of collapsing systems of taste, today’s bohème rehearses a preemptive impression of proletarianisation (‘white trash’) as a means of upward social mobility. Per cacus ad astra. The few become stars, the majority will be forced out of this new creative zone as they were previously forced out of nearby, now-gentrified, Shoreditch.

...the square should become a public forum, an outdoor living room for all the people of Hackney – Gross Max Architects

The mobile man, the precarious tenant and the artist are secretly aligned. If the square, or anywhere else in the fluid Hackney Zone of Exception, is ever going to approximate to ‘a public forum’, it will be as a self-instituted focus for the silent majority’s unwanted desires. Eli’s isolated last ditch stand against the forces of regeneration must become collective, interconnected and expansive.

Eli’s army will comprise all the ASBOs (anti-social behaviour orders) of the zone, all the refugees and untermenschen, from the hooded youth to the tramps to the tenants associations and those artists not satisfied with just recycling the entropy of the area, anyone who for their specific reasons cannot but revolt against this systematic shut down of urban space. Against the siege mentality of the gated communities and ‘affordable apartments’, a boundless, truly fluid and self-proliferating siege engine that spreads across the city like a plague.

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com