No Room to Move: Radical Art and the Regenerate City

Critiques of the instrumentalised role of culture within the current stage of urban development, so-called ‘culture led urban regeneration', are becoming increasingly common. A rising crescendo of criticism may finally be denting the blithe confidence of the ‘Creative City' formula and its liberal application to all manner of post-industrial urban ills. Criticism, but also and more forcefully, that other party crasher – the global financial crisis – are undermining the blind faith in the power of ‘creativity' to heal our cities. But regardless of what the post-crunch strategy for treating urban decline may be, we can now begin to see with clarity the contours of a (now waning?) form of urbanism that has developed over the past 20 years. One whose mobilisation of art and aesthetics – and particularly a post-conceptual order of aesthetics – has worked to produce the propagandistic illusion that a substantial regeneration of society and its habitat is occurring. It is, however, one that masks the unaltered or worsening conditions that affect the urban majority as welfare is dismantled, public assets sold off and free spaces enclosed. We feel that the spectrum of analysis of urban regeneration must necessarily entail an aesthetic one since public art and architecture are not only often complicit within this stage of development, but also offer moments and forms in which power and counter-power negotiate, clash and find articulation. To understand the dynamics of cities in their neoliberal capitalist phase, then, it is not enough to look at the structural and economic questions alone – we must also investigate the visual languages and conceptual approaches of the aesthetic activity apparently valued so highly by their elites.

Given the enormous scope of this question, however, our focus will be narrower, restricted here to art that occurs in what can loosely be called public space, even while it does not always necessarily understand itself as ‘public art'. Indeed, we are interested in art practice that engages consciously with the multiple crises of public and/or community art, the so-called public sphere and of art's instrumentalisation within an entrepreneurialised landscape of funding bodies, commissioning agencies and institutions. The very act of situating art in public space creates both an index of these crises, their meeting point and a discourse on the economic, political, technological and bureaucratic conditions that give rise to them. We are interested in work that consciously opens up these tensions to examination and intervention.

Image: Roman Vasseur & Diann Bauer, Palace of Utopias, temporary gallery located in Harlow's Market Square, 2008. Photograph by Richard Davies, courtesy of Commissions East

Our focus has also been constrained by limits on time and resources which have meant that the interviews, which form the basis of our research, all took place with artists and consultants living and/or working where we live – in the South-East of England. In any case, Greater London single-handedly provides more ongoing cultural regeneration projects than one could comprehensively survey within the reasonable limits we had set ourselves. Rather than making a survey, the interviews we have made sample critical artists working in and against cultural regeneration, all acutely aware of the tensions and contradictions that this work entails. The list of interviewees is: Alberto Duman, the art collective Freee, Nils Norman, Laura Oldfield Ford and Roman Vasseur. Each interview was conducted through an initial meeting followed, in most cases, by an email exchange. Our focus throughout has been on theoretical and practical models of analysis and engagement, and the practical experiences artists have encountered through their work in regeneration contexts. The article itself sets these interviews within a historical and thematic exposition of the art and culture of the ‘regenerate city'. Despite our expectations that such an analysis would crystallise predictions about the future of the city and the art it engenders, we found it almost surprisingly rare for our interviewees or ourselves to venture bold statements to this end. At this point it is perhaps enough to describe more accurately the shape of the present in order to set down the proper conditions from which multiple futures may lead.

Creating the Creative City

The demise of one form of production, which demands and is predicated on the arrival of a new one, transforms the physical environment of the city. Former productive spaces are rendered obsolete and become available for new uses as the city's spatial arrangement is reordered to accommodate new forms of production and consumption, and patterns of habitation. Today's so-called Creative City, organised around the prosumption of data, knowledge and culture and the consumption rather than production of material commodities, finds its roots in the post-war period. The LCC's 1951 Administrative County of London Development Plan contained within its apparent modernism the blueprint for the postindustrial development of the UK's cities.i Involving the monumental centralisation of resources as well as the standardisation of county planning departments, the plan argued for a city based around sanitation, the expansion of green spaces and the opening up of waterfronts to pedestrian access. Crucially, it encouraged the movement of industry, manufacturing and food markets to the peripheries of cities.

Large-scale, post-war civic development took advantage of the devastating wartime bombardment of cities such as London and Liverpool, but also responded to a confident and militant population who, after the hardships of six years of war, demanded higher living standards, modern accommodation and cleaner cities. Paradoxically, the massive 'slum clearances' carried out in working class areas which were supposedly offset by a vast social housing building programme, resulted in a net population decrease in London.ii Working class populations were displaced to the surrounding counties of Essex, Kent and Surrey which saw the redevelopment of market towns such as Romford, and later the creation of New Towns like Harlow. This early deindustrialisation had not yet taken the visionary form of the 'leisure society' which was to emerge in the 1960s, but its transformation of the inner city was a crucial step towards the creation of a city geared to the needs of the post-Fordist economy. The ensuing 'entrepreneurial' model of urban transformation which began to develop in the late 1970s, in contrast to the earlier 'heroic' modernist phase, would be characterised by the twin and highly related phenomena of gentrification and so-called 'regeneration' equally vilified and celebrated by opponents and boosters.iii Each of these models represent responses to the social and productive crisis left by the displacement of manufacturing from the inner city, as well as the break down of the post-war social compact between labour and capital by which the State became primarily responsible for social, hence also urban, reproduction.

Image: Aerial painting of the Festival of Britain, 1951, by Brian Tilbrook and his father. Constructed from plans of the site before its construction, it became the only aerial image of the festival and a popular postcard

'Gentrification' was coined as a term in 1964 by sociologist Ruth Glass to describe the movement of affluent individuals into lower class areas. Initially an ad hoc phenomenon, gentrification has increasingly been engineered by first local and now global networks of real estate developers and speculators. The outcome of gentrification is usually increased property prices, increased revenue to local governments from property taxes and the displacement of the lower income population. Artists have frequently been at the forefront of processes of gentrification, famously in London's Shoreditch and New York's Lower East Side.iv Often their role in gentrifying an area has been unintended, an effect of the much touted ‘buzz' that concentrations of artists create when flocking to an area in search of low rents. However, artists are often deliberately used as avant-garde gentrifiers by real estate agents and local governments, or act consciously as developers themselves, going into impoverished ‘wastelands' to set up the beacon of yuppie-attracting culture. Indeed, Shoreditch estate agents Stirling Ackroyd specifically targeted adverts for short-life live/work leases at artists (whom they cynically termed 'scuzzers') in order to gradually build a rental market and attract investment in property into the area.v

Albeit that the purely ‘natural' phenomenon of urban gentrification is largely a myth, the term ‘regeneration' nevertheless registers a shift from a relatively emergent model of development to its specifically state-led form. Regeneration attempts to stimulate gentrification through the establishment of quasi-state agencies, tax breaks, re-zoning, public subsidy of private development, the privatisation of local resources and the deployment of culture. In the cases listed above, initial developer-artist-led ad hoc forms of gentrification were followed by a second phase of state-led regeneration. Modelling themselves on the ideal of a self-organising free market, regeneration agencies have sought everywhere to maintain the illusion that the market is the driver of positive change. Underfunded by central government and bombarded by neoliberal ideology, local councils have executed something like the IMF's Structural Adjustment Programmes upon themselves, transferring council housing, schools and leisure services into private hands. In place of secure, centralised funding schemes, boroughs, like cities themselves, have been oriented towards project funding in the form of regeneration grants. Where direct state funding or intervention is often seen by the private sector as the State muscling in on potential business opportunities, public funding for culture, by contrast, is perceived as neutral and beneficial. But culture-led regeneration has failed to mop up the fallout from a contracting economy and ailing productive sector. Following the financial crisis the response has not been a turn to productive investment to aid crumbling private-public services and the education sector, but rather just an extreme commitment to state-underwritten market solutions on a bigger scale than ever. Thus, state intervention remains as prevalent as before (indeed state investment in the UK economy has risen steadily under the market fundamentalist stage of capitalism) but has simply changed its ideological guise – the State bankrupts itself to make it seem as if the market is working.vi

The roots of state-led regeneration proper developed in the wake of the inner city riots which erupted across Britain's cities in 1981, in London (Brixton), Liverpool (Toxteth), Birmingham (Handsworth) and Leeds (Chapeltown).vii Then Secretary of State for the Environment, Michael Heseltine, was given the role of troubleshooter tasked with resolving the causes of this explosion of violence and popular dissent. The solution he came up with revolved largely around the role of culture and sport (notably, not economics) in calling to heal the violent anger of those forgotten inner city populations.

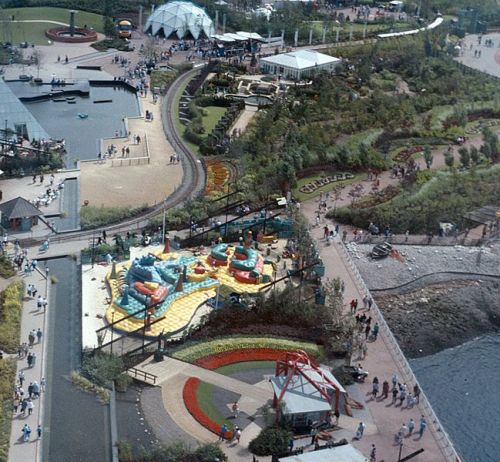

Aside from a renewed and patronising focus on youth and sports clubs, Heseltine's response also entailed a series of Garden Festivals in Liverpool, Stoke-on-Trent, Glasgow, Gateshead and Ebbw Vale (South Wales) which proffer an early model of 'cultural' regeneration in the UK. They were typically placed in derelict industrial sites near to working class areas, and unlocked large tranches of public money to clear sites, purify land, improve transport links and eventually transfer land to private developers. At each of the Garden Festival sites, special agencies such as the Merseyside Development Corporation were established to attract private capital investment and lead regeneration in areas undergoing post-industrial decline. These quasi-autonomous non-governmental organisations (QUANGOS) were directly appointed by the minister and overrode local authority planning controls, a measure which proved controversial in Labour strongholds such as East London, Merseyside and North East England, but also prescient of later modes of large-scale development in the '90s and '00s.viii

Image: An overhead view of the 1988 Glasgow Garden Festival site

The Garden Festivals recalled the fanfare and populist cultural pageantry of the Festival of Britain, a motivational rebranding – treating urban problems as psychological rather than socio-economic – which Roy Coleman characterises as engineering a form of 'urban patriotism'.ix The festivals were intended to enhance the cities' public image, attract tourism, and build the momentum necessary to attract inward investment. Yet unlike the Festival of Britain, none of the festivals left any lasting architectural or cultural legacy. Afterwards Garden Festival sites either lay derelict in the hands of developers who bought them up or were transformed into private residential dwellings. Culture was deployed to re-engineer significant areas of cities and coordinate the interests of the local government and private capital. Aside from a brief moment of euphoria for some, each festival was a resounding cultural and social failure, but would become a success story for capital in the medium to long term as new areas of development were opened up, planning laws waived, and land remediation costs paid for by the State.

Artists on Both Sides of the Barricades

Despite constituting a largely itinerant and opportunistic community motivated by the search for cheap rents, artists have often been forced to take sides in the onward march of regeneration. Either as ‘culturepreneurs', producers of public art, model subjects for urban economic development, or threatened residents, artists' involvement in regeneration's history is practically unavoidable.x Before looking at the negotiation of critical artistic practice within urban regeneration zones, we will consider briefly some pivotal moments in artists' collusion with and contestation of the regenerate city.

The London Docklands Development Corporation (LDDC) was one of the QUANGOs established by Michael Heseltine to regenerate the vast area of East London's Docklands. Prior to the establishment of the LDDC, the Docklands were home to a traditionally militant working class of former dock workers and, increasingly during the 1970s (when the docks began to close) and through the early '80s, a fledgling scene of artists and squatters. Derek Jarman's film Jubilee (1978), set in Wapping, seems to epitomise the apocalyptic decadence and class recalcitrance of this period of post-industrial malaise.

Punk disaffection aside, the redevelopment of the Docklands did, in fact, meet with fierce resistance from members of the local community, trade unions, local artists and squatters. Nonetheless, the nature of artists' involvement in the struggle remains open to debate. A collaboration between Peter Dunn and Loraine Leeson, local action groups, trades councils and residents of the Isle of Dogs protesting the enormous divestment of services and destruction of community that the Docklands Development involved has provided art history with an exemplary model of artists fighting against regeneration. In their Docklands Community Poster Project (1981-1991) Dunn and Leeson made a number of billboard posters for sites around the area using classic montage techniques and motifs derived from the work of John Heartfield. These 18 ft by 12 ft billboards identified what were collectively felt to be the most important issues affecting the community:

Unlike conventional hoardings or community murals ... the posters were completed on a gradual basis so as to establish an active narrative interest in the work's progress. As such the hoardings functioned as both an information board and as a symbolic site of resistance to the unbridled development.xi

The work highlighted the inequities of the deal the LDDC was offering to the local working class community and the interests of big business which lay behind it. Nonetheless the aesthetic model was that of classic agit-prop, advocating on behalf of a public who was consulted but also rendered somewhat inert through the process of being spoken for. The art of Dunn and Leeson is also open to accusations of art's instrumentalisation by social agendas – in this case those of the trade union movement – and by subordinating its critical faculties to a 'good' cause, the Poster Project succeeds as ideology but fails as critical art.xii

On the other side of the barricade, as it were, concrete relationships developed between the LDDC and the emergent young British artists (yBa). At the time of early Docklands development many artists had spaces leased from the LDDC via ACME studios. When Damien Hirst was looking for a location for a large group exhibition he approached the LDDC directly.

Damien Hirst achieved mythical status with the Freeze exhibition, which he curated in 1988. Partially funded by the London Docklands Development Corporation, sponsorship was given on the understanding that it would be of benefit to the community. With the LDDC, Hirst negotiated the use of a building belonging to the Port of London Authority in Plough Lane to curate a show of his work and the work of his Goldsmiths contemporaries. The YBAs were born.xiii

Image: Still from Derek Jarman's film Jubilee (1978) set in a blighted Docklands

This complicity fits in with our image of Hirst as the very paragon of the Thatcherite artist as ‘culturepreneur'. Mouthy and a bit of a chancer, Hirst directed himself towards the emergent powers of his era, in art (curator Norman Rosenthal and collectors Charles and Doris Saatchi) and in governance (the LDDC). The relationship between Hirst and the developers of London's Docklands raises the question of how the State and business use art and culture to carry out economic and social change through regeneration. It is clear that at points artists' and developers' interests coincide, but to what degree? And how conscious was the LDDC's use of the arts as a strategy for raising the economic value of property in a blighted area of the city? Throughout the 1990s there were a litany of examples of collusion between individual property developers and artists looking for raw available spaces. Later the property game became a revenue stream as developers, architects and corporate firms employed art consultants to source art to decorate their 'great spaces'. Increasingly artists who produced for themselves and their peers were drawn into professionalisation: production for a developing art market. Did Hirst simply make a connection via the 'umbilical cord of gold' posited by critic Clement Greenberg, which ties artists to the elite, revolutionising the UK art market almost by accident, or had a more reciprocal structural shift in the relationship between artists and free market capitalism taken place? What is certain is that thereafter regeneration's relationship to art became increasingly integral and self-conscious.

Itinerant Agents Meet the Community

As well as this individual spirit of entrepreneurialism and its complicity with the new economic forces, there were also collective, self-organised corollaries which had more to do with the spirit of punk and DIY culture than professionalisation. During the 1980s ACME – an organisation managing artist's studios – became a lynchpin of a growing artistic scene in London. The history of ACME is significant because not only was it an artist-run organisation, but also because it pioneered the supply of artists with both studios and affordable living accommodation at a time when the market for contemporary art was far smaller, and hence survival as an artist much harder. The price of acquiring affordable space was, however, constant precarity and the closer relationship of artists with less than benign urban development. As artist Pete Owen recounts,

ACME was set up by two artists, Johnathon Harvey and David Panton in 1972 to provide cheap studio and living accommodation for artists. It also ran a gallery in Shelton St., Covent Garden, London from 1976-1981. Their short-life houses were in generally poor condition with very basic facilities. They were relatively cheap to rent with the occupants agreeing to do most repairs. There were between fifty and one hundred artists in the Leyton/Leytonstone/Wanstead area. These houses were licensed from the Department of Transport as 'short' term lets. In a politically dodgy situation they had been compulsorily purchased by the Department of Transport over a period of time purposefully and gradually blighting the area where they proposed to build a motor way link road through the community. They assumed that once owner occupiers had been removed there would be little resistance.xiv

When in 1987 the decision was announced that the M11 was to go ahead and many of the houses were to be demolished, a part of this small community of artists began for the first time to really engage with its neighbours and a local campaign to stop the link road was catalysed.

A sizeable chunk of the local population was about to be decanted, but it was not like we were a real community, we were artists – sort of itinerant members of society but we did make up a sizeable chunk of the local population.xv

As ACME began to empty the houses, few artists resisted. Many artists didn't want to break their relationship with ACME since they would lose the opportunity of a new studio or housing elsewhere. However, small groups of artists, squatters and locals began to reoccupy ACME houses as they became vacant, used squatters rights to prevent their demolition and thus held up the scheduled road-building.

Just as every legal means of blocking the road had been exhausted, the arrival of protestors from Twyford Down and the Dongas Tribe signalled a change in direction for the Stop the M11 campaign. The Dongas Tribe was a collective of squatters, travellers and artists who pursued a fusion of life, art and protest. Occupying empty buildings in the path of the motorway, they creatively reconfigured terraced houses and the street into open air cinemas, cafés, gardens, playgrounds and barricades. Claremont Road became a symbol of artistic and environmental protest, its Victorian terraced houses and street transformed, for many, into a paradigm of art's power to transform life, and vice versa. Though by this point the campaign was lost, the Dongas' example attracted widespread media attention and the M11 protest became a seminal moment that was to make a lasting impact on protest culture and art for a decade afterwards. Despite the involvement of many artists early on in the campaign, few had considered putting their art at its service – the influx of new protestors inspired the older guard. Artist Paul Noble who had been involved early on in the campaign began to fix home-made blue plaques onto derelict houses in the path of the road (a trick later copied by Gavin Turk to egotistical ends). The inscription on the plaques read:

Our Heritage

THIS HOUSE WAS ONCE A HOMExvi

The work, an example of unauthorised 'public art', foregrounds a struggle over history which has animated creative engagements with the urban environment. Noble's plaque could be said to be minumental rather than monumental and points to self-organised attempts to commemorate the collective experience and unrecognised histories of the city within its fabric. Positing an 'us' which is constituent and prior to the 'public' it coheres a minor community of identification. Monuments are after all, as Anthony Vidler notes, always 'agents of memory', yet exactly what agency this memory carries is left open to the contingency of history and subsequent attempts to activate it.xvii Even as public art has moved away from monumentalism there has been a distinct turn towards the mining of cultural memory and the contestation of history. Stuart Brisley's placement in the new town of Peterlee, set up by the Artist Placement Group (1976-2004), pioneered an approach to local 'history from below' now endemic to public art. Brisley established a collection of photographs taken and donated by local people recording the disappearing life of the pit villages whose end the New Town augured. The photographs were then housed in the council archives – an act of enforced conscience and memorial on the eve of the ruthless dismantling of Britains coal mining industry. Brisley's project was an insistently collective one in which the artist stood aside to allow people to make and organise their own historical record.xviii So often now, however, this gesture is mimicked by artists hired by agencies to toothlessly commemorate the communities imperilled by the same regeneration they administer. As part of a recent festival, The Story of London, sponsored by Mayor Boris Johnson, a multimedia walking event presented participants with audio recordings commemorating the history of Leyton and the struggle against the M11 link road. The whitened bones of history, now considered safe from the fecundity of decay, are conjured as character-giving heritage in newly sanitised city districts.

Image: Tower at a Stop the M11 squat on Claremont Road, Leytonstone, 1994

Clearly, the agents of regeneration do not regard the art works which often mediate these histories as a potentially inflammatory ingredient to be treated with extreme caution. Whilst routing around overtly controversial work, nevertheless commissioning bodies display an openness to art's unconventionality and even criticality. When one imagines how comfortable developers are when engaging artists, and how at the same time they would never dream of soliciting public acts of expression from socially marginalised groups such as the unemployed, the perceived tameness of art is revealed. It is this perception of art as a social and environmental enhancer rather than destabilising agent or potential cause of blockages within the smooth functioning of the city, its populations and productive flows that explains its popular integration into regeneration schemes. Furthermore, for city councils, underfunded since the Thatcher years and directed towards policies which draw in revenue (primarily from raising council tax, selling off estates and imposing parking fines), driving privatisation and gentrification through culture looks like the cure-all solution to make both a quick buck and rapidly transform the image of the city.

The popularity of the turn to culture for 'economic' ends in many of the UK's cities is described by Neil Gray in the context of Glasgow's East End, where what was since the 1970s an area populated by artists has recently been re-branded, from above, as 'creative':

From a situation where artists and squatters had once led gentrification, albeit unconsciously, an instrumental policy framework is now firmly in place whereby city officials do the leading as they seek to enhance property values through the cultural capital of artists and the creation of a ‘creative cluster' in the area now re-branded as the ‘Merchant City'.xix

Ironically it is the upwards transaction of 'cultural capital' which will likely jeopardise many Glaswegian artists' activity in the area. As Gray goes on to point out, rather than the magical transformation being promoted by the City, what is in fact happening in the 'Merchant City' is primarily the shift of existing art spaces, such as Transmission Gallery, from low rent council property to high rent 'creative' property managed by an agency on behalf of the council and its investment partners. Attempts by local councils to rebrand and regenerate an area have frequently involved commissioning public art and funding arts initiatives to give an area colour and life. But whilst the benefits for developers and councils are made plain, there has been little attention in critiques of regeneration to what has motivated artists themselves to participate. It seems future generations of artists will continue to face the contradictory bind of being both beneficiaries and losers in the path of capital's movement of creative destruction (each time on reconfigured terms and conditions).xx And as art and artists have become more integral to contemporary urbanism, they have also become increasingly astute critics. Yet moments when artists resist development and gentrification directly have been rare. Art works more often mount an aesthetic resistance or, as Jacques Rancère would say, a ‘redistributrion of the sensible'. Critical art in urban settings survives development's horrors, maintaining a tension with the context of its production and, in the best cases, amplifying them. Rather than writing off art altogether as either 'for or against' regeneration, could we apprehend aesthetic experiments in the tensions they establish with their contexts and the forces which attempt to direct them?

Here Comes the Mirror Man: Pundits, Planners and Policy-Makers

How did art come to be considered an economic driver? And how did a 'creative industry' emerge from the ruins of industrialisation? According to an early critic of the creative industries, James Heartfield, the Arts Council itself was partly responsible:

The fashion for counting the creatives began in the 1990s when people like Andy Feist, Jane O'Brien and John Myerscough started tabulating the census to estimate employment in the ‘arts sector'. People have forgotten, but at the time this was a rearguard action. The Arts Council, where a lot of that original research took place, was on the defensive. It had lived through a decade of cuts in public money for the arts - so different from today. The point of their various papers and reports was to make the argument that far from being a drain on the exchequer, the arts were a boon to the country.xxi

Heartfield goes on to argue that initial attempts to quantify and attribute value generated by the 'arts sector' led to research which would ‘creatively' assign all sorts of positive economic indicators to the whole of culture in the broadest sense possible (e.g. the manufacture of CDs).

This dynamic played out in quite specific ways in the case of public art – or art in the expanded field – a growing area of interdisciplinary practice from the early 1970s. Public art agencies, who played a critical role in the explosion of public art commissions over the past three decades, developed out of critiques of the white cube as well as an attempt to redress the London-centrism of the UK art system. Malcolm Miles recounts how this new crop of art managers, albeit intending to promote regional and emerging artists, were transformed by the Thatcher government's imposition of a corporate model onto the arts:

As a consequence of their required adoption of a business model, public art agencies began to lobby (separately and via the Arts Council) for policies such as Percent for Art, and for art as a driver of urban renewal, by which their sector might be enlarged. The case for art as a solution to the problems of inner-city decline, or a means to revive zones of de-industrialisation, was made successfully. Art's expediency is now regarded by most city managements as a norm. Yet the idea of art as a cosmetic solution for problems produced by failing infra-structures, at root by other areas of government policy, was contested then and haunts public art's histories now.xxii

As Miles points out, cultural management on a business model also resulted ‘in higher-status, higher-budget projects, and a global approach to the selection of artists'. The reverse of the anti-hegemonic logic which had initially driven agencies like the Public Art Development Trust (PADT).

It seems that the directive flow from government to the arts may, in a modest way, have reversed itself as the criticality of art is solicited not only to embellish regeneration schemes but, nominally at least, to influence their conceptual planning. One of the newer agencies to fill the emerging space for art on the frontiers of urban regeneration is General Public Agency (GPA), which meshes identity politics, critical and community art practices, architectural theory and social geography to generate research and policy for planners, developers and regeneration agencies. In short, the agency (run by curator Clare Cumberlidge and former director fo the Architecture Foundation Lucy Musgrave), takes an art-inspired approach to the technocratic science of planning. Its product is creatively inflected urban strategies for planners, developers and regeneration agencies. One of their biggest and most significant commissions was to develop a policy brief for Thurrock in the Thames Gateway – one of Europe's largest regeneration projects. This area, which sits between three administrative districts (London Thames Gateway, North Kent and South Essex), covers 800km2 and contains 3,000 hectares of previously developed land east of London. A key methodology used by GPA was a ‘creative mapping' of the area, involving experts (urbanists, environmentalists), artists and locals. The hope was that they could engender a more imaginative approach to Thurrock's regeneration and thus avert the ‘blanket of low-grade dormitory housing' everyone feared. A central part of this exercise was their mapping of local knowledge and cultures which had been thus far overlooked. GPA's high regard for culture and histories of ordinary people, and the importance they place on its inclusion into urban strategy is something that shades into what they have elsewhere termed ‘new social practices' – a term we understand to refer to the creativity of everyday life. This latter, claims Cumberlidge, is sidelining the importance of art's role in the public sphere as curators, practitioners and funders increasingly submit to market logic. ‘The more it looks like art' she ruminates, ‘the less effect it has.'xxiii GPA begin to look like a more efficient, specialised and professionalised alternative to hiring actual artists. They suggest the possibility, of which as we will see artists themselves are not unaware, that the era of the public artist may indeed cede to that of the creative manager.

Image: Still from Neil Norman's graphic novel Thurrock 2015

It is telling that these ‘new' social practices Cumberlidge speaks of cannot just be left to exist in a state of nature. For them to become significant enough to be recognised by professional thinking they must first be framed by experts. One such example of this is a GPA commissioned book by Bridget Smith entitled Society comprising a sequence of photos of the interiors of London social clubs and associations. An evocation of the apparently ‘real' or vernacular culture of London, these unfamiliar lifeworlds are elevated, made proper, through high spec photography and an art catalogue style lay-out. Despite the fact that there is something unconvincing about GPA's simultaneous love of the everyday and their desire to transform it, GPA's approach has nevertheless led to some shift in the thinking around regeneration. Cumberlidge claims that the policy recommendations that arose through the consultation at Thurrock, despite being passed over by the incoming Tory council and newly established Urban Development Corporation, were later incorporated into Arts Council East and East of England Development Agency's joint prospectus. She claims that their methodology is now being used nationally.

The tensions between the role of the expert and that of the layman or unpaid non-expert that we see manifested in the work of GPA, are becoming standard within public art practice. The artist is often required to leave their specific disciplinary training at the door, or dissemble their skills and critique within a vernacular mode of address – while the science of cultural management seems to have become increasingly internalised and naturalised. With the fashion for dialogism in art becoming something of a prerequisite to gaining commissions, the artist must increasingly adopt a consultative rather than prescriptive methodology, or risk being sidelined. But as many shun the knowledge/power of skilled work, or posture at doing so, others such as Nils Norman and Roman Vasseur have become interested in the ‘aesthetics of bureaucracy' and the potency of mastering the methodologies and aesthetics of urban planners and developers as a way to intervene more effectively in the neoliberal development of cities. Indeed, Cumberlidge pointed out that one of the problems of art in the context of regeneration is that once it has been ‘delivered', the process of dialogue and discussion comes to an end. Artists like Vasseur and Norman attempt to get around the short-termism of target or output culture by inhabiting the processes of planning, policy and governance themselves.

Vasseur, who we will come to below, has been appointed to the role of ‘lead artist' during the redevelopment of Harlow, a post-war New Town in the Thames Gateway. Norman, who has made the neoliberal development of the city one of the key subjects of his work for over a decade, was also one of the artists invited to respond to GPA's Visionary Thurrock brief. His publication, Thurrock 2015, takes the form of a graphic brochure exploring cultural and environmental scenarios possible in the context of the development of the Thames Gateway in the era of climate change. Norman's work, typically composed of diagrams and cartoons, performs a canny suspension of the movement towards the full instrumentalisation of art to fit social agendas. By setting his invented scenarios in a none-too-unfamiliar near future, the coincidence of methodologies used by top-down governance and planning, relational or socially engaged practice and cultures of protest are gently satirised, projected and modified. Whilst Norman advances a radically subversive ecological agenda, it remains in the realm of projection and ambiguity, thus open to questions of contingency, critique and alternative propositions.

I see what I am trying to do and what I have done in the past as a form of critique rather than reform. To be able to actually stand in an urban planners office and tell the planners and council members that what they are doing is crap rather than rhetorically state this in a group show to the curators who organised it, seems more relevant within the context of this sort of art activity.xxiv

Far from feigning dilettantism, Norman is interested in gaining access to highly skilled and elite sectors of urban governance and commercial development, opening up their processes to imitation, scrutiny and debate. The strategy of projection as critique intervenes at a charged stage in planning processes, that of the plan or diagram in which the future of a site is imagined. Models, plans, maps and computer-generated images of future developments are frequently used to sell a site both to its existing inhabitants and to future buyers and renters. In a deterritorialised and image-obsessed cultural economy, projections and visual representation of as yet unrealised places are often the channel through which they are circulated and consumed, and through which desires are constructed. As the virtual is increasingly loosed from the physical – the site dematerialised in Miwon Kwon's terms – this imagined site has become a plane of struggle and a place to insert alternatives and assert other agendas. Norman's satirisation of developers' and planners' ability to fabricate (and sell) a potential future reality before it has happened is inverted to produce a similarly flattened yet feasible landscape of radical alternatives.

Image: Freee, The economic function of public art is to increase the value of private property, billboard poster, 2004

The art collective Freee (Dave Beech, Andy Hewitt and Mel Jordan), whose art practice can be described as making art about public art and its social and economic ‘functions', are quick to correct any notion that the public sphere is reducible to a series of physical sites:

[...] we do not operate in public spaces or public places, but in the public sphere. The question of site seems to reduce the question of the public sphere to special designated official physical places (town squares, parks, civic buildings and so on) but for us the public sphere includes any act of publishing or making public, so that means it can operate in a pamphlet in your pocket or a private commercial gallery. No site is more public than another on account of its physical qualities or official designation.xxv

Clearly then, the annexation of the ‘public sphere' by capital involves not just the squeeze on ‘free' spaces which people can occupy without being required to consume, but also the colonisation of our collective ideas of the future of the urban environment largely fabricated through virtualisations and mediation – a mode of imagineering quite vulnerable to artistic and political disruption. Or, as Freee would have it, borrowing their terminology from Oskar Negt and Alexander Kluge, media and its circulation are the means through which a ‘counter-public sphere' can be advanced.

The Art of Governance

A mutual inquisitiveness and mirroring between art and governance has been building since the 1960s. A cursory history of this development could plot a line from the Artist Placement Group and their early pioneering of industrial and governmental placements, (1960s/70s), to Joseph Beuys and his ecological schemes for urban regeneration (1980s), to Roman Vasseur's current advisory role within Harlow's redevelopment (2000). This trajectory involves the transformation of a perhaps naïve, but deeply earnest desire on the part of artists to know, and subtly influence governmental and commercial decision making processes. Yet this inquisitiveness has gradually been subsumed into the state's cynical deployment of ‘creatives' as soft cops working on the front line of social inclusion. Joseph Beuys stands at the mid-point between the two – on the one hand apparently sublimating the exceptional status of the artist into his concept of ‘social sculpture', while on the other rivalling and undermining the role of local government through his charismatic interventions. A project which importantly prefigures the contemporary role of art within regeneration today, and especially its recent ecological turn, is 7000 Oaks, begun in Kassel in 1982 as part of Documenta 7. People were invited to take an oak tree and plant it somewhere in the city next to a basalt stone which the artist also provided. The scale of the project and its attempt to forge community through the activity of civic (and thus self-) improvement, tip this public art work over into something on a par with a public works scheme. From small acorns, big things grow – these days art is solicited by the state in lieu of significant public works schemes, and as a place-branding device under the new entrepreneurialised modus operandi of local government which seeks to attract inward investment rather than concentrate on the provision of social infrastructures and welfare.xxvi

But, as importantly, public and community art are used ‘biopolitically' in an attempt to mobilise or ‘activate' people into refounding their communities. As artist and curator Alberto Duman has pointed out, the dual meaning of ‘regeneration' as both biological re-growth of cell tissue or whole limbs, and the act of bringing areas of the city back to life is no accident.xxvii The rebuilding of the city's physical fabric is also and always a reconstitution of its living inhabitants. It should be remembered that this more bio-technological image of ‘regeneration' has roots in ecological visions of growth and healing which are in turn couched in the anthropocentrism of such concepts of balanced nature. Talking about 7000 Oaks, Beuys commented:

I think the tree is an element of regeneration which in itself is a concept of time. The oak is especially so because it is a slowly growing tree with a kind of really solid heartwood. It has always been a form of sculpture, a symbol for this planet.

Albeit in a continuum, it is nevertheless a stretch from Beuys' sustainable model of social growth to the fire-fighting strategies of forced social cohesion in evidence today. With New Labour creating more criminal offences during their time in office than any other post-war government (approximately one a day under Blair's government), their ideal of building strong and healthy communities through popular participation is based on a thinly disguised, underlying coerciveness.xxviii At the time of writing, new plans are being developed for a points-based citizenship system in which applicants could be penalised for ‘unpatriotic behaviour such as protesting against British troops'.xxix Just one in a long line of moves to make rights contingent on highly determined responsibilities. It is the presence of this hyper-invasive control of subjects that makes the recent flowering of public art begin to look less than benign. Freee are only too aware of the project that creativity is being recruited to:

Regeneration does not boil down to gentrification. Gentrification is about Real Estate. Regeneration is also about getting people to behave differently. It goes on in schools, with the criminal population. It is social policy more than anything: education, aspiration, employment, the economy and so on.xxx

It is interesting to remember that the Artist Placement Group had, only several decades earlier, wanted to get business and government to behave differently through the intercession of the artist or ‘incidental person' ['IP'] as they called the interloping artist. Inserting creativity into government was, perhaps, perceived as a way to break the stranglehold of empirico-rationality and systems geared to capital accumulation. Now, as welfare is attacked, community assets flogged off and imperialism unable to hide its naked ambitions behind a veil of nationalism, government and capital need to find new ways to penetrate the subject, to ‘activate' people into becoming community members. Meanwhile, the very notion of commonality on which community is grounded is dismantled by the sell-offs, marketisations and dispossessions perpetuated by free market capitalism (Public-Private Finance Initiatives and the creation of an internal ‘market' for health ‘services' within the NHS being just a few glaring examples). The recent explosion in public art in the UK must relate partly to the crisis precipitated by the neoliberal enclosures of the city within a more general setting of real subsumption in which social reproduction is commodified. Community is killed off only to be ‘regenerated' in zombie-like form, a living dead state of social (non)reproduction and officially orchestrated sham spectacles of being together.

Image: Beuys planting the first of the 7000 Oaks in front of the Fridericianum in Kassell, 1982. Photograph copyright of Dieter Schwerdtle Fotografie

And what form of art arises as a consequence? As with the piazzas, statuary and symbology of old, the public art of today likewise bears the insignia of its master – capital. Its universalising force of equivalence leaves an indelible impression on contemporary art as openness and interchangeability become some of its defining characteristics. We have only to think of Trafalgar Square's fourth plinth with its constantly rotating piece of contemporary sculpture for a literalisation of how equivalence – albeit in the guise of democratic inclusion – takes hold in the UK's most high-profile sculpture park. Indeed Anthony Gormley's recent work for the site, One and Other, literally swaps the living occupant of the plinth on an hourly basis. At the other end of the scale, equivalence is produced in terms of the pseudo-embrace of community in public art schemes where artists are employed to fabricate totemic symbols of integrated communities (which are usually undergoing a traumatic transformation and disintegration at the hands of the very parties who are funding the art work). In a work indicative of this idiom and its contradictions, Shop Local (2006), artist Bob and Roberta Smith mounted five large text pieces around Shoreditch in the style of 19th century hand painted advertisments. Apparently celebrating 'the importance of the local entrepreneur as a key component of any thriving community'; at the brink of this figure's complete disappearance.xxxi Such totems are often created not through the singular response of the artist but through the risk-deferring mechanism of consultation, in which supposedly all ‘gangs' are given equal representation.

But, as Saul Albert experienced when working as one half of the art collective The People Speak on a community art commission in Bow, London, there is a big gap between funders' views and those of the community's as to what constitutes legitimate forms of self-expression. After a very successful attempt to create a collectively designed mural for a local kick-about area through a game-show style event in which local gangs and teenagers improbably took part, the funders attempted to censor part of the proposed mural. The funders objected to the inclusion of ‘inappropriate imagery' (copyrighted cartoon imagery) and the gang tag ‘E3 Bow Massive Shank Shank'. Having made concessions to the funders' demands, The People Speak presented a neutered version of the mural back to the community, and so lost the hard won trust of local gangs who walked away. They were left with a lesson:

[...] we gained insight into a term that seems to recur with many participatory art and regeneration projects that engage various gangs and unaffiliated individuals in an area and call it a ‘community'. We learned that each of the gangs, including our own, can be part of a community of competing gangs, but that in order for that community to exist, every gang has to have a voice.xxxii

However, the idea that ‘inclusion' into collective articulations of desire, or forms of group self-expression, can solve the structural nature of social inequality is at best idealistic. Indeed, as Giorgio Agamben has pointed out, inclusion has become the very form by which exclusion is perpetuated. According to Agamben, our contemporary biopolitical moment focuses on a form of population management by which each of us is counted (plotted, databased, inscribed etc.) but none is recognised. A relation of power that he terms ‘inclusive exclusion'. Such is the rhetorical trap of 'openness' – a mediating operation by which intensities and antagonisms are diffused. How then can ‘communities' manifest without lending themselves to the state's need to ‘activate' them for a pre-defined purpose (social reproduction as labour power), becomes an increasingly fraught issue.

Image: Roman Vasseur, 'Wreath for Sacrificed Artist' from Murder as a Fine Art (the Ritualised Death of the International Mural Artist), 2004

Meanwhile, many artists concur that ‘the public' does not exist, and have become interested in the impossibility of producing a public, most especially through the intercession of art. This refusal of the terms and referents of public art has itself become a sub-genre of art in public places. The neo-conceptual artists of today no longer celebrate national identity, proud national accomplishments, military and cultural heroes, but prefer often to problematise the lure of public art. Nevertheless, in eschewing such specifications of identity while creating art in public places, the spectre of equivalence and openness constantly re-emerges within many art works.

This openness, argues Roman Vasseur, is highly compatible with the new face of capitalism:

Notions of the Avant-Garde and its ensuing risk taking, openness and emphasis on dialogue, and activated and participatory audience are all factors that have led to neo-conceptual practices having a compatible symmetry with the growth of knowledge economies and the culture industry in recent years. But it is the very openness of these practices that becomes their sole content.xxxiii

Music theorist Jacques Attali has argued, in a similar vein to Vasseur, that cultural censorship develops in the form of a bias towards the laws of political economy. In liberal capitalism, those laws constantly espouse freedom and openness while de facto reinforcing the hierarchies of privilege. This rhetorical adherence to openness is silently reproduced across the network of funding and selection, as those in positions of power comfortably echo the once radical gestures of the avant-garde while keeping faith with the doxa of (neoliberal) economic health.

From the faux humbleness of Bob and Roberta Smith's sign art, to the universal standard of humanity offered by Anthony Gormley's Angel of the North, inclusion has become the stigmata of a neo-conceptual practice which seeks a neutralising and quietist mode of public address. Neither leaving any one out, nor including anyone in, it recalls the fake portrayal of everyday life produced by Socialist Realist propaganda only without the ambition of perpetual revolution. In the 'megagentrification' going on around the London 2012 Olympic Park, virtual graphic projections of a modernised and flattened playscape paper over the very real conflict and displacement which the dramatic transformation of a broad zone of East London has entailed.xxxiv Here, the virtual assumes primacy over the real. A kind of corporate multiculturalism and futuristic pastoral coexists: avatars shop, exercise and spectate apparently freed from the service work, debt and alienation upon which the vision itself is predicated.

It is perhaps due to this shared attempt to include everyone through the exclusion of no-one, to be inoffensive and to reassure through the adoption of cliché and familiar symbolism, that projects as apparently dissimilar as Mark Wallinger's proposed 50 metre high sculpture of a white horse at Ebbsfleet and Bob and Roberta Smith's community art projects become directly comparable. Discussing regeneration agency Commissions East's inclusion of both artists as part of the artistic quotient of the Thames Gateway's regeneration, Alberto Duman identifies the apparent schizophrenia of their anti-monumental and mega-monumental commissions:

The antidote and the ‘poison' are therefore administered by the same doctors, like some social placebo, each targeting a specific constituency and delivering a specific ailment. [...] Sculptural or architectural landmarks for big business, socially-engaged art for the community: The ethos of ‘choice' offered across the spectrum of approaches makes sure that mechanisms of clear identification between activities and their targets (or cultural products for cultural customers if you prefer) defines each one's respective camps without collisions.xxxv

Image: Bob & Roberta Smith, Dad's Unisex Hair Salon, 2006, off-site installation on Hoxton Street. Part of his Shop Local series

Openness, inoffensiveness, social participation and (exclusive) inclusion, art-in-public-space that recognises the fiction that is ‘the public' but which wants to engage ‘communities', the quest for identity within a cultural moment that meticulously flags its contingency – these are the tools developed by well-meaning, even radical, cultural practitioners now deployed by state managers, developers and culture brokers. They signify the 'democratic' values of our age through which we experience an ambient criticality which demands an end to the lies public art has historically force-fed the masses, whilst helping to sell the bigger lie that culture can ameliorate the problems of an economy in a prolonged state of post-industrial decline. The obsession with participation, we must surmise, is an inverse index of the extent to which we have become socially atomised. Or, as the anonymous authors of The Coming Insurrection write in response to the excesses of a recent Reebok slogan 'I AM WHAT I AM'',

My body belongs to me. I am me, you are you, and something's wrong. Mass personalization. Individualization of all conditions - life, work and misery. Diffuse schizophrenia. Rampant depression. Atomization into fine paranoiac particles. Hysterization of contact. The more I want to be me, the more I feel an emptiness. The more I express myself, the more I am drained. The more I run after myself, the more tired I get. We treat our Self like a boring box office.xxxvi

As ever, the role of art is to cover over the brutalities of society, to remind us of our civility, to insist on our connection to a human community, to instil good liberal democratic values into us. In other words to rid us of the self-obsessed, individuating residue bestowed by capitalist social relations and our continual exposure to advertising campaigns like Reebok's. And the knowing art of the neo-conceptual, post-punk generation poses little threat to this function it seems.

The Art of Pleasure

However, this over-focus on the panacea of the arts within the context of urban regeneration is more than a redoubled campaign of embourgeoisement in the face of deepening urban blight. It is also a marker of power learning to speak ever more fluently in the aestheticised language of pleasure and the commodity form. A way of producing the spectacle of place in the image of luxury goods sitting in shop windows – the suspension of these goods in the forever time of the as-yet-unconsumed; the place that Disney princesses ride off to at the end of the story. These new public spaces (Hackney's Gillett Square or, on a more epic scale, Chicago's Millennium Park) must remain as untainted as Snow White's dream castle since they repulse participation in all its manifold, unruly forms, whilst symbolising participation at a higher level, as a spectacle for the enjoyment of the ambling citizen.

Or where participation is directly solicited – the Diana, Princess of Wales Memorial Fountain in Hyde Park or the restaging of Robert Morris' 1971 interactive sculpture Bodyspacemotionthings at Tate Modern (May - June 2009), for example – we see it in its most innocuously docile, picturesque and unproblematic guises. Laughing children skipping about in a glorified, granite water slide or, in the latter case, people queuing diligently while the fitter amongst us test their physical prowess in ergonometric constructions. Highly interactive, play-ground style art works like Morris' highlight the trends and economies of the new emporia of cultural consumption. Art becomes a pretext and organising principle around which can cohere the economics of mass tourism, the regulated bio-economy of family entertainment, and the assimilation of fitness and body aesthetics into the structured cultural life of the city. When Morris' work was first shown at the original, neo-classical Tate Gallery it incited frenzy:

gallery-goers seem to have temporarily lost their marbles. People tore their clothes off as they leapt up Morris's plywood slides. Minor injuries were sustained. Mini-skirted dollybirds got splinters in their bottoms. After four days, the Tate's then director, Norman Reid, closed the whole thing down.xxxvii

By summer 2009, as The Telegraph's reviewer notes with disappointment, crowds patiently queued under the watchful eyes of ‘walkie-talkie wielding guards' ensuring that there was never an excess of exuberance, and that everyone got to take their turn. Popular participation in art works has become a predictable and scripted affair, but it has also become a sure-fire way for curators to guarantee ‘foot fall' in the gallery. For those new spectators who now flock to, rather than flee, the hallowed halls of art, it can function as a cheap alternative to a day out at Alton Towers; something for all the family and with excellent café and toilet facilities to boot.

Image: Installation of Robert Morris' 1971 piece Bodyspacemotionthings at Tate Modern's Turbine Hall

These new audiences for art have grown up in a time in which life in general has become hyper-cultural; the leaden mail-outs from local housing services must disguise themselves as lifestyle magazines, groups of friends advertise and commodify themselves for each other via social networking templates, and even down-at-heal sea-side refreshments stalls disguise a shit instant coffee as the more cosmopolitan cappuccino. Half a century of consumer society has produced an insatiable appetite for aestheticisation. So, despite the increasing lock-down and personalised tracking of populations within the cybernetic matrices of the post-9/11 state, the aestheticisation of space reveals that the powers-that-be must choose their mode of address more carefully than ever before. Control must deploy the veneer of health and happiness to get things done. Or, in Foucauldian terms, governmentality uses aesthetics to penetrate the subject more deeply, to tap into our capacity for self-government. In the biopolitical era, discipline meshes with techniques of the body converting ‘care of the self' into portals of intrusion and introjection, and hijacking the DNA of pleasure to other ends. The philosopher Maria Muhle has rejected interpretations that take Foucault's term ‘biopolitics' to designate a form of power which now takes life as its object, arguing instead that it is a modality which possesses a positive and not a repressive relation to life:

My claim is that biopolitics is defined by the fact that rather than merely relating to life, it takes on the way life itself functions; that it functions like life in order to be better able to regulate it.xxxviii

If power has become life-like, it has also become art-like. This is a worry for those concerned with art's need to be distinct from the rest of life, to antagonise or reveal new forms of sensibility. Although New Labour's 12 year rule has been a boom time for art – not least public art – the blanding out of notions of creativity (such as those espoused by Richard Florida and his followers), and the discovery of art's ‘social purpose', leave its future in doubt. As Vasseur surmises:

One can envisage a future where artists, or individuals with an extensive training in visual arts and art history will be slowly moved out of this new economy in favour of ‘creatives' able to privilege deliverability and consultation over other concerns.xxxix

So while avant-garde attempts to negate the privileged role of art and artist are purloined by government and the leisure industry, or applied to pseudo-democratic ends by developers and commissioning agencies, or used ultimately to eject the artist from the culture-society equation – what recourse do artists critical of the ‘creative industries' model have to making art in public? Is it even possible to make critical art publicly any more?

From Arcadia to Chinatown?

As ever, in order to look forward, it helps to look back to an earlier model of art's use in the (re)construction of community amidst urban upheaval. Roman Vasseur's engagement with Harlow involves ‘disinterring' the original thinking behind this petite New Town, as it stands on the brink of wholesale expansion and redevelopment.xl Vasseur has spent a great deal of time thinking about how its master-planner, Frederick Gibberd, attempted to forge community in the aftermath of WWII, and with the fresh canvas of a greenfield site. He is fascinated by how technology – coupled forever with the power of mass extermination after two world wars – is understood not as something that threatens ‘Arcadian visions of Britain', but as that which can create them anew. Gibberd used new, mass-produced elements in the construction of the town, introduced the first residential high-rise block into Britain, and one of the first covered shopping malls. But despite this, he wanted to found the new community on the ancient values of religion, family and co-operation – as witnessed by his extraordinarily detailed, Elizabethan-modernist design for the town's St. Paul's church (1959) and the prominent siting of Henry Moore's sculpture of a family group in the water gardens as the visual centrepiece of Harlow.xli But Vasseur also draws attention to the ‘Dionysian' impulses that underpin and threaten Gibberd's ‘Apollonian' ordered ambitions for the town. He sees them as relying upon the atavistic forces of religion and the emotive creation of a community spirit centred around the pioneering moment of exodus from the metropolis and, consequently, a static model of inclusive exclusion. As Vasseur points out, Harlow sits in what has been termed by Rem Koolhaas a ‘mega-region'; its positioning making it highly vulnerable to assimilation into the surrounding conurbation. Its residents, says Vasseur, are about to be ‘radicalised'. At this juncture, he thinks, it would be wrong to perpetuate the local identity that the town has nurtured for so long. But what is to follow, and what role should art play within this transformation?

Image: Henry Moore's Family Group in its Harlow town centre site

The town's unique atmosphere is largely a result of the the centre's setting in a parkland of green wedges which connect it to the outlying residential areas. At the heart of this radial and highly ordered design sit a canonical array of public sculptures by post-war British sculptors like Henry Moore, Barbara Hepworth, Lynn Chadwick and Elizabeth Frink. Says Vasseur,

Harlow's distinction is that it employed and embodied culture and in particular sculpture to make an argument for the creation of a settlement away from the metropolis but referencing the Tuscan City State model.xlii

Vasseur's engagement with the town is markedly different from the paternalistic example set by Gibberd who also headed the Harlow Art Trust which selected the town's public art works. It should be noted that Vasseur's role has been consultative and curatorial rather than directly artistic. Nevertheless, his approach could be interpreted as an artistic intervention in its own right, despite his insistence that he is not a ‘career public artist'. Indeed, like Nils Norman, Vasseur tends to operate in a more undercover mode; a kind of contemporary version of APG's ‘incidental person', but one actively solicited by Commissions East – one of the regeneration agencies involved – with the agreement of the town council. Unlike APG's artists however, Vasseur experiments with the strategy of ‘overidentification' with the bureaucratic process. For instance, while seeing ‘the public' as a phantasmatic entity deployed by government for its own ends, he nevertheless invokes the term within negotiations as a ‘reprimand', or a means to rein in full-throttle commercialism. In such a way, Vasseur uses the bureaucratic or commercial body's logic against itself and, in so doing, turns the often crushing process of negotiation into a ‘sensual pursuit'.

His approach seems influenced by the tradition of institutional critique, especially its later tendency to play with overidentification, such as Andrea Fraser's gallery tours which drew attention to the service culture of the museum while staging a grotesque overidentification with its language and grammar. Rejecting any purity of revolutionary or artistic purpose, Vasseur comments, ‘Artists in my experience are not willing to wait for revolutionary change in order to express their sensuous beings and so are disloyal to communities of politics.' But his work in Harlow is not without specific aims or the desire to have some lasting impact. He was drawn to the role because it was advertised as ‘the first time that an artist would work on a committee selecting a developer-planner'. He has also presented an architectural review of some of the proposed redevelopment plans for the local councillors – a potentially very influential opportunity. But, at the recession ridden time of writing, the future of the redevelopment looks uncertain, and no developer has yet been selected. The ‘aesthetics of bureaucracy' are, of course, hostage to the movement of the bureaucratic process itself, its glacial time frames, and the macro-economic picture, all of which can be enough to kill off the initiative and desires of the undercover interventionist. Where Gibberd's art programme can be seen as conservatively retrograde, Vasseur's mercurial approach – in seeking to expose the Dionysian and violent impulses which belie modernism as much as preserving its achievements in the face of junk-space development – seems to lack definition and hence traction within the process of the town's transformation. The town, albeit consulted and invited to participate in a series of events and discussions organised by Vasseur, seem stranded between Gibberd's nostalgic and untenable idea of community, and Vasseur's position of cynical reason that is helpless to assert any alternatives. It is tempting to think of the role of today's regen artist in the mould of Jack Nicholson's ex-cop character in Polanski's Chinatown, who, when asked what kind of police work he did in Chinatown mutters ‘As little as possible'. It was the only way to avoid making a bad situation worse.

At odds with Vasseur's image of the artist as disloyal sensualist is the work of Laura Oldfield Ford, whose drawings, fiction and public interventions play on the immediatist and conflictual politics developed by groups such as Class War. In a wasteland-palimpsest of past and future ruins, outcast youth and graffitied walls admonish the class enemy. 'Yuppie scum', 'loft living victims of future crimes', developers and estate agents are all targets of abuse and explicit threats of violence. The climate of fear and invocations of ‘Broken Britain' used to justify regeneration are here depicted with almost comic hyperbole to the opposite effect. In her drawings and zines, the ‘undesirable' elements are the heroic avengers of a class and mode of life that have been transhistorically excluded from the city. Oldfield Ford's outing of the urban landscape's codified class relations occurs within several representative fields: in the gallery, on the street both as flyposters and during performative walks and 'drifts', and on the printed page in the form of the xeroxed zine Savage Messiah. Whilst the same antagonistic imagery threads through these different media and sites, Oldfield Ford is equivocal about the location of this work in gallery spaces.

I don't think working class anger can be mobilised by putting drawings in a gallery but there are other important elements of my practice such as flyposting and making zines, putting on free events that create hubs for discussion and debate.xliii

Oldfield Ford's practice seeks to activate the image of the outsider – everyone who has been excluded and disabled by the new geography of neoliberal capitalism – as a counterweight to the production of smooth space. Rather than an art practice which seeks to heal wounds in the social order, her work is directed towards an inclusion of what cannot be included in the prosecution of existing interests, and an amplification of the tensions and antagonism this process brings about.

Regeneration schemes are about the remaking of the city in the cast of the bourgeoisie, about eradicating the ghosts and projecting holograms in their place... my zine Savage Messiah and projects related to that are about chronicling the city, about mapping the city along the contours of hidden narratives and oppositional currents.xliv

To what extent this antagonism depends on the stable image of an enemy which may or may not exist is a question worth raising. For, if the imagery of clean, young, white professionals relaxing in their secure technologised environments is a fiction of advertising which belies a reality of overwork, insecurity, debt and alienation, then Oldfield Ford's work also produces its reciprocal oppositional fiction of outcast militancy. Structurally these are each projections which clothe in personifications, social relations in which we are perhaps as much at war with ourselves as with our class enemy. From Ikea to Lidl, between the privatised council flat and the gated 'luxury' complex, class demographics in an era of generalised proletarianisation are increasingly resistant to reduction into easy signifiers. Both projections apprehend class as cultural rather than material and thus promulgate a war of representation and identities which elides our mediation through capital.

Image: Laura Oldfield Ford, page from her zine Savage Messiah

Oldfield Ford's psychogeographical practice has its roots in a scattered, early 1990s scene of antagonistic and irrationalist creative street actions involving political activists, artists, musicians and just plain weirdos. Groups such as Inventory, the London Psychogeographical Association, The Manchester Area Psychogeographic and the Association of Autonomous Astronauts among many others, published on, graffitied and walked the city in an effort to open its past and existing organisation to radical critique and desiring activity. Inventory staged a series of actions called Coagulum at which ad hoc groups would meet in the lobbies of shopping centres and form a headless collective body, like a rugby scrum, simultaneously blocking commerce and opening up non-spaces to new forms of ludic behavior. The AAA staged games of three-sided football in urban parks, subverting competitive sport in embodied 'trialectical' critique of existing social space. The LPA made a series of walks in small groups through the city irreverantly deploying avant-garde tactics, magic and speculative history in a multivalent assault on reason and enlightenment values. These actions and walks as small crowds in the city were adamantly non-artistic and non-professional, producing little remainder other than the printed matter or emails publicising the events and the small fields of intensities they opened up during their ephemeral formations. Throughout the ‘90s, these explicitly politicised groups – often as critical of the organised left as they were of the coercion of everyday life under capitalism – shared city space and certain techniques with postmodern ambient culture. Sound systems, squatters, skateboarders, pirate radio operators and street gangs also littered the streets with arcane signs and graffitti – internal communications for those in the know. These groups' activities could be contrasted with the ambient culture critic Neil Mullholland describes as being related, yet depoliticised:

Nineties artists re-examined ambient critiques of spatial temporality, remodelling maps and re-exploring ‘alternative' psychologies of space from a perspective that was politically detached yet aesthetically absorbed by late avant-garde tactics.xlv

Mullholland argues that as the '90s rolled on, these postmodern interventions in the city, graffiti, culture jamming, flyposting etc., became increasingly interchangeable with the growing sector of outdoor and 'ambient' marketing.

[...] the latter half of the [‘90s] saw ambient forms of jamming become increasingly common in European advertising, mirroring the impact of the recession on artists working in the built environment. In Britain, ambient advertising, a fledgling sector in 1995 worth £10 million, is expected to be worth £110million by the end of 2002. Ambient strategies have varied enormously, ranging from guerrilla marketing stunts, viral e-mails and fly posting to targeted text messaging. Environmental art has been heavily sourced by guerrilla stunt-driven outfits such as Cunning Stunts [...]xlvi

Image: Inventory and others performing their circulation blocking Coagulum in an unknown shopping mall

Equally as the signifiers of informal art and culture could be re-deployed to the ends of advertising, it would appear that with the massification of modern art spectatorship, even now in the 21st century after more than a century of self-organised art groups and artistic attacks on the categories of art and the avant garde, a star system prevails to an even greater degree. Last year Tate Modern held a large retrospective of 'Street Art'. Massively popular, it marked both the final recuperation of grafitti and the reification of 'the street'. The blockbuster exhibition simultaneously brought street art into the gallery and commissioned and gained public license to create art in the street, thus neutralising any remaining illusions of a tension between the street and the museum. The exhibition fully incorporated street art into its own logic of cultural production and consumption, subsuming even the myriad ad hoc 'interventions' around it. This last bastion of the street artists, apparently autonomous and spontaneous, has now been put to work under the logic of professionalisation. This process can be seen most plainly at work on the front-line of East London's regeneration at the point where the advancement of the City of London meets the culture-led regeneration of the East End. Opposite the Rich Mix centre on Bethnal Green Road a massive construction project to convert Bishopsgate Goods Yard into a commercial centre is under way and graffiti artists have been commissioned to decorate the billboards which surround the site. For years the semi-derelict buildings in this area were covered in graffiti and posters. Only at the final moment of their destruction is this extra-artistic activity brought into the process which will re-make the area on entirely new terms – 'official' street art signals the reorganisation of previously unruly self-activity under the 'norms' of wage labour.

Waking out of Dreamland