Children of the Grave vs Moloch

The exhibition, Home of Metal, celebrates forty years of heavy metal music while foregrounding Birmingham’s industrial past. In an act of ‘dedicated mining’, Cameron Bain follows metal from its birthplace in heavy production to sonic home for vital antagonisms

Birmingham’s claim to be the ‘Home of Metal’ hinges primarily on the generally accepted notion that Black Sabbath, from Aston, were the founders of the genre. Certainly within metal circles this is standard lore. (Also hailing from Birmingham and its environs, Judas Priest and Napalm Death, too, play prominent roles in the evolution of metal and thus in the exhibition, but more on them later.) Plausible cases can be made for earlier manifestations of the metallic form, say, Link Wray’s ‘Rumble’ (1958), with its epochal, soundbreaking (sorry) deployment of the power chord, or the Kinks’ ‘You Really Got Me’ (1964), with its foregrounding of two features that would become key sonic components of metal, namely: DISTORTION and the bludgeoning, repetitive primacy of the RIFF.

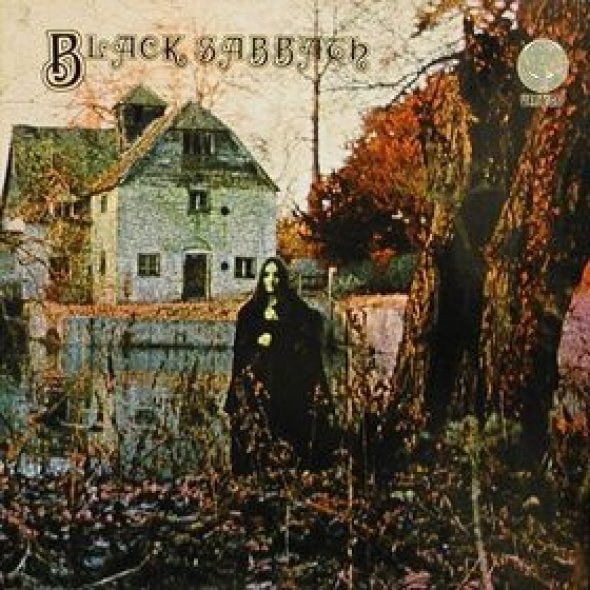

It was with Black Sabbath’s eponymous debut album, though, (released February 1970), that many of the elements that would become enduring metal tropes, even signifiers of the genre, were distilled into an uncanny, potent brew for the first time: the creepy tritone intro riff (the Devil’s interval) of the opening track 'Black Sabbath'; spooky rain sounds and tolling bells; lyrical themes dealing with being hounded or seduced to damnation by satanic forces (‘Black Sabbath’ and ‘N.I.B’ respectively); Lovecraft-referencing/paraphrasing song titles (‘Behind the Wall of Sleep’); a desolate acoustic interlude sounding more menacing than pastoral (‘Sleeping Village’); and cover art redolent of a Hammer Horror, complete with morbid symbolist poetry framed by an inverted crucifix in the gatefold. Interestingly, the band had no involvement in the sleeve design; the designers presumably latched onto the same commercial impulse as the band itself when they appropriated the name Black Sabbath from Mario Bava’s 1963 horror (the original Italian title was I Tre volti della paura – The Three Faces of Fear), having speculated that if people were prepared to pay money to be scared in the cinema, perhaps they would also pay to listen to ‘scary music’; metal bands, for all that they may relish their underground, outsider cachet, have, in the main, always wanted to actually sell records.

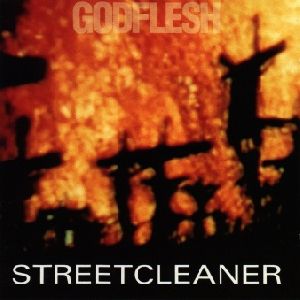

Image: Godflesh, Streetcleaner album cover, 1989

The story as told by the exhibition at the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, however, begins with the city itself and the influence of its sonic and material environment on the nascent musical form. A pair of wall quotes introducing the exhibition paint a picture of the city as heroically doomed to labour, a hellish crucible of raw, elemental heavy production:

Birmingham began with the production of the anvil and probably will end with them. The sons of the hammer were once her chief inhabitants.

– William Hutton, First Historian of Birmingham, b.1723

Black by day, red by night…

– Elihu Burritt, American consul, 1862

Part of the formative myth of metal is that the insistent pounding of Birmingham’s foundries had a direct influence on the unrelenting martial rhythms of the music, as well as informing a bleak, pessimistic outlook born of reflection upon the fate of those consigned to live out their lives amidst the remorseless grind of the urban industrial environment. It’s a thread that runs through the reminiscences of many musicians in the Birmingham lineage, from the video interviews with the members of Black Sabbath and Judas Priest included in the exhibition to a recent interview given by Justin Broadrick to Terrorizer magazine, recalling the psychic ambience surrounding the making of Godflesh’s 1989 album, Streetcleaner:

At night, in the summer with your windows open in the flat that I lived in, you could hear deliveries to these shops, and in the background were these factories. The smell in the air was industry and the sound was literally of grinding machines all night – it was like living in Eraserhead! I obviously felt at odds with that urban hell and Streetcleaner was definitely me trying to articulate what I had been through and harbouring that sort of hate and negativity.

The first room of the exhibition includes a display of some of the machine tools responsible for generating the city’s unholy permanoise, as well as interview recordings with the men who used to operate them – (I liked that this crucial industrial background to the emergence of the music was treated more than just tokenistically, that some effort was made to communicate the grain and grit of what it was like to actually labour in one of these factories in this place and at that time). This display, complete with time clock, could also perhaps be seen as a stark summation of working class youth’s horizon of expectation: manufacturing machine as implacable destiny and memento mori. In addition it serves as an oblique allusion to another element in Sabbath’s (and thus metal’s) sonic template: it was a similar kind of machine that removed the tips of two of Sabbath guitarist Tony Iommi’s fretting fingers; the result being that, having ingeniously fashioned a pair of prosthetic fingertips out of washing-up bottle tops and scraps of leather, he ended up downtuning his guitar, finding the slacker strings easier to negotiate with his artificial fingertips. With the downtuning Sabbath acquired their signature ‘doomy’ sound. An interesting lecture that I attended as part of the exhibition touched on the importance of local amplification technology (Laney amps) in the formation of this sound also, but I will pass over that, uncertain as I am of the casual reader’s interest in such guitar geek tech specs.

The next room in the exhibition is a mock-up of a ’60s sitting room, featuring such retro curios as period television set and cigarettes. The room, besides offering somewhere cosy to screen the video interviews mentioned above, functions as one pole in a juxtaposition between the low-key, domestic escapism of lounge and TV on the one hand and the flamboyant, grandiose escapism represented later in the exhibition by displays of Judas Priest’s guitars and stage outfits and extravagant stage props, like the giant cross from Sabbath’s 1981 ‘Mob Rules’ tour. Metal is often derided for this grandiose escapism, ridiculed for its rich proliferation and dedicated mining of ‘ludicrous’ Tolkienesque/Lovecraftian/medieval/Viking/horror/sci-fi themes, but to denigrate metal’s presentation and thematic material as mere escapism is to miss a couple of important points. Firstly, for the working class youth (as was) comprising the membership of bands like Black Sabbath and Judas Priest, metal’s ‘escapism’ represented a literal escape from what appeared to be an ineluctable, stultifying factory fate. As the members of Judas Priest tell it in one of the interviews, regardless of any academic promise you might have shown in school, the question was not ‘what do you want to do?’, but ‘which foundry do you want to work in?’ (Incidentally, there is a refreshing lack of tedious pull-yourself-up-by-your-own-bootstraps cant in their musings on where they find themselves now as compared to where they could have been – the connection to the ‘real’ life of the community and its history still seems very strong, another justification for the inclusion of the humble sitting room, I think.) In fact, one of metal’s tacit, more laudable themes might be ‘Escape more! Escape better!’

Image: Judas Priest, Sad Wings of Destiny album cover, 1976

The second point I would make with respect to the accusation of mere escapism, is that for all that metal certainly does rely heavily on the exploitation of fantastic themes, it has always (or at least since Sabbath’s second album, Paranoid) also explicitly tackled political themes, often vividly and insightfully. War, the threat of nuclear annihilation (admittedly more in currency during the Cold War), the destruction of the environment, genocide, existential despair rooted in grotesque social inequalities, the creeping pathologisation of ‘awkward’ ‘personalities’ (for want of a far better term) and drug (ab)use are all amongst the ‘issues’ that have become perennially ingrained in metal’s lyrical DNA.1 One of my favourite metal diatribes against the iniquities and anxiety that seem to characterise ‘modern life’ is Sabbath’s ‘Hole in the Sky’ (echoes of depictions of the medieval ‘abominable fancy’?), from their 1980 album Sabotage, wherein we find a pithy analysis of the band’s own compromised role in the industrial production of art: ‘the food of love became the greed of our time / and now we’re living on the profits of crime’, giving the lie to the popular myth that, because metal bands seem to exist on a plane of ludicrous, ‘escapist’ excess, they are somehow bereft of any sense of self-awareness.

Image: Napalm Death, 'Scum' album cover, 1987

Metal’s most explicit and ferocious exercise in political engagement and critique arguably reaches its apogee with Napalm Death, the third major band forming the backbone of the exhibition. Napalm Death’s metal influences (Celtic Frost, Possessed) combined with more political hardcore punk (Discharge, Siege) and post/crust punk (Killing Joke, Crass, Amebix) to essentially form a new genre: grindcore (the name being coined by Napalm Death’s insanely fast drummer, Mick Harris). The resulting music is truly avant-garde in its condensation of speed, volume, concision and fury. ‘You Suffer’ (the shortest song ever recorded (1.316 seconds long), according to that magnificent compendium of spell-bindingly useful information, The Guinness Book of Records), from the debut album Scum is a detonation, a one-off sock in the gut that manages to both pose a question still painfully relevant and to be an exhortation to liberatory analysis: ‘you suffer / but why?’

The section of the exhibition illustrating the (ongoing) Napalm Death episode in Birmingham’s metal story contained what was probably my single favourite display, a huge collection of memorabilia from the milieu from which they emerged, loaned from the personal archives of members of the band(s): handwritten Napalm Death setlists (’83-’86) and lyrics; handmade gig flyers and posters for multi-band bills (the band names highlighting just how remarkably connected nationally and internationally the obscure local scene was); myriad anarcho-punk zines; and demo tapes and mixtapes with song titles in faded biro. Everything in fact, that constituted the distinctive verbal, visual and audio aesthetic fabric of the time, a microhistory of mass communication of an underground movement in the pre-internet age. The fact that such a wonderful proliferation of lovingly preserved self-documentation exists speaks volumes, I think, for the conviction and sheer enthusiasm of those involved, an eloquent and enduring testimony to youth’s dedication to being righteously (and rightfully!) pissed off. How you have fun (how you ‘escape’) counts and, given the state of things, the attitude celebrated here seems more vital and necessary than ever. Nostalgia doesn’t come into it.

Cameron Bain <cameronbain AT hotmail.com> works in the library for the School of Slavonic and East European Studies, writes sometimes and sometimes plays music in the bands Vukojebina and the Hung Jury

Info

The Home of Metal Exhibition was held at Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery 18 June to 25 September 2011

Further Reading

Ian Christe, Sound of the Beast: The Complete Headbanging History of Heavy Metal, London: Harper Collins, 2004.

Ozzy Osbourne, I am Ozzy, London: Sphere, 2009.

Albert Mudrian, Choosing Death: The Improbable History of Death Metal and Grindcore, Washington: Feral House, 2004.

Chuck Eddy, Stairway to Hell: The 500 Best Heavy Metal Albums in the Universe, New York: Da Capo Press, 1998 (NB. Eddy’s definition of what constitutes heavy metal is tendentious and notoriously catholic – basically it’s anything with loud guitars – but the book’s full of sharp, funny writing about loads of good music, metal or not).

Footnotes

1 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0zsHo5SpGbc&fbclid=IwAR0MlQkbJvHzhWK4DosQHyBfpn2f9dXli41w9egNNCJiBWyab466YhiKR_4 Black Sabbath performing ‘Hand of Doom’, live in Paris, 1970. Despite (or because of) the band’s own proclivities at the time, they manage to come across not as hypocrites, but as sincerely furious and compassionate.

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com