Style Without Subversion

The V&A’s Postmodernism exhibition acted like an industrial trawler, disembedding three decades of cultural artefacts from their diverse ecologies. The result, writes Gail Day, is a deeply conservative reading of this tumultuous epoch

Most people seem to like the exhibition Postmodernism: Style and Subversion 1970-1990. Such, at least, was the evidence on the night I attended (and from much of the general chit-chat one picks up, and from the cheery presence of promotional leaflets spotted in fashion outlets). Admittedly, I went to the museum on a Friday late night opening when, in the V&A’s foyer, a sound system was pumping out music, cocktails were flowing and families were learning a technique for darning holes in jumpers. It was also the night when Charles Jencks was talking to Rem Koolhaas; both have work displayed in the show, so I imagine they must have been in good spirits – and the crowd spilling out from the discussion into the Postmodernism exhibition was generally enjoying the fun of it all.

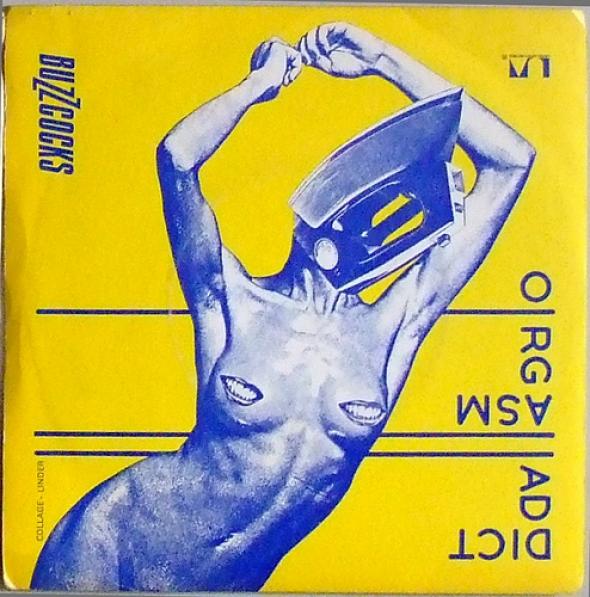

As may be inferred from my tone, I didn’t. Sure, I found plenty of pleasures to revel in – vicarious and otherwise. Tapping toes to Talking Heads, snippets from Blade Runner and The Last of England, issues of The Face, a Buzzcocks’ single, and reminders of the Hacienda: it was a retro fairground of an earlier life. Lots of stuff I’d thrown away. My own petty possessions and experiences of the ’80s were raised to a second power under the museological gaze named ‘postmodernism’. At least I had enjoyed using the commodities back then; with their fetish nature transmuted, they looked back at me from their cultic vitrines and display monitors. Interestingly, the temporal economies invoked by the items of popular culture (the mags, the films, the sounds, the looks) didn’t accord with those of the furniture and household objects. If coming across the former felt like rummaging at a jumble sale, the latter was more like window shopping in one of today’s emporia, with their Alessi franchises, devoted to designer products. Not all commodities are equal. Of course, for anyone of my generation, the show inevitably had a melancholic underpinning. But, irrespective of when we were born, Postmodernism treated the reminder of death as a deliberate leitmotif. Jencks’ words, stencilled on the wall, set the scene from the outset: if modernism is dead, ‘we might as well enjoy picking over the corpse’. Later, Derek Jarman’s voice-over was used to echo the sense of historical caesura and closure: ‘Even our protests were hopeless’.

The V&A’s institutional form shaped the exhibition in two ways. First, the architectural spaces used for the museum’s temporary displays forced a tripartite division and, secondly, the focus of the museum’s collections gave direction to the type of materials used to typify postmodernism (jewellery, furniture, etc.) The first section largely focused on architecture, drawing on the texts written by architects and theorists who were considered to have initiated the visual and material dimensions of postmodernism: Jencks, Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown, and James Wines. (This was not the place to worry ourselves much over Jean-François Lyotard’s, Frederic Jameson’s or David Harvey’s accounts, never mind the arguments of postmodernism’s critics.) The second part was largely geared towards a range of design media (furniture, graphic design, etc.). The last section attempted to situate postmodernism in relation to money and the commodity and included, inter alia, jewellery, craft and examples of a peculiar high-end phenomenon where architects would be commissioned to conceive a ‘piazza’ of coffee accoutrements. This final section abandoned the lightbox signboards of the two earlier rooms (red and green respectively) in favour of an abundant use of shiny-black acrylic sheets. The coloured glow associated with commercial promotions in streets and subways was displaced by reflections that conveyed the air of an aspiring celebrity funeral. The exhibition’s parts narrated, loosely, the three-fold time frames of postmodernism: its coming to ascendancy, its high period and its collapse (‘under the weight of its own success’). As a heuristic device, this seemed remarkably conventional. Methodologically, it was something of a dinosaur, especially with the treatment of the final phase as one of internalised self-regard (remember those accounts of the renaissance giving way to mannerism, the baroque to the rococo… or, for that matter, modernism to the international movement?). This conceptual conservatism also emerged via the show’s subtitle. Accompanied by its subset of associated binaries (theatrical/theoretical, commercial/avant-garde, etc.), ‘Style and Subversion’ was posed as the overarching ‘ambiguity’ – the all round refusal to be categorised – that was (allegedly) postmodernism. Postmodernism, we were told, was ‘a new self-awareness about style itself’. But it transpired that Postmodernism, the show, reduced ‘style’ to an unreflexive, art historical category which was used to pin down a period of 20 years: strange to see because, if the debates over postmodernity did one thing, it was to distinguish ‘ism’ from ‘ity’.

One would be hard pressed to know from Postmodernism that the period under scrutiny saw a massive assault on working class communities and labour organisations; significant battles over racist and sexist discrimination, gay rights, abortion rights and anti-Nazi activism; the deregulation of the financial markets; the beginnings (in the UK) of the attacks on free university education and the dismantling of the postwar welfarist settlement. The categorial blanketing performed by ‘postmodernism’ evaded the specificity of the objects qua material objects, let alone the objects as socially situated entities or actors. To reprise the earlier conjuncture: Jarman’s angry lament, eight years into Thatcher’s term, was fundamentally at odds with Jencks’ suave ease and intellectual game playing. It is critically lazy to dub such differences ‘ambivalence’. Postmodernism-as-idea effectively bludgeoned into subjection every object presented. There was insufficient recognition that while some claimed to be postmodern, self-identifying as its promoters, others only became identified as ‘postmodern’ by dint of being turned into the tokens within the arguments of the time. For a good number of the exhibits, the label ‘postmodern’ seemed to be being freshly applied; just being a product of the ’70s or ’80s seemed sufficient. That surrealist inspired Buzzcocks’ cover? It was news to find that the youth of the ’80s ‘experienced postmodernism for the first time through issues of The Face and i-D’. No! The curators’ opening statement ducked the point: ‘This era defies definition, but it is a perfect subject for an exhibition.’ Which era doesn’t ‘defy definition’? Clearly, we were meant to answer ‘modernism’. Empty truisms of this sort peppered the show – along with their associated straw target – while reheated paraphrases (‘we are all postmodern now’) fell short of carrying off pastiche.

Bricolage was a running theme. Loraine Leeson and Peter Dunn’s Big Money is Moving In, from the project ‘The Changing Picture of Docklands’ – an intervention in the radical (‘left-modernist’) montage tradition – found itself reduced to an example of ‘postmodern technique’. Working with tenants’ action groups and trade unions to oppose the gentrification and corporatisation of their neighbourhoods, the artists developed a series of large publicly sited photo-murals. Shorn of its resistive voice, its activist identification and its commitment to collective agency, the work just served to underscore the closing section’s ‘money’ theme. Earlier we were told that, while modernism created unified wholes, postmodern montage was variable, apparently ‘embracing the full diversity of the world’. The ‘modernists’ named as exemplary of the ‘synthesised’ mode were Hannah Hoch and Kurt Schwitters. Had the curators actually looked at their work? Along the same lines, we learnt that modernism equates to the grid: a bizarre statement to make when you include, as an example of postmodernism, a celebratory riff on Manhattan’s street pattern (Koolhaas’ Delirious New York). The force of the ‘postmodern’ chopper came down, conceptually cutting history into trite isms and categories. But – despite what the literature promoting postmodernism claimed – the history of montage practices does not divide itself up into an era of unities and an era of fragments; and neither does the 20th century.

Image: Charles Jencks, Garagia Rotunda, Truro, MA 1976-77

Nevertheless, it was surprisingly interesting to encounter key tokens from its discourse. Despite serving as postmodernism’s ideological juggernaut (or perhaps because of it), the architectural material proved especially fascinating. Even the reconstruction of Jencks’ Garagia Rotunda, his automotive ‘garden folly’ dressed up in stagey classicist motifs – though it did strike me all the more powerfully as boringly naff – provided a welcome opportunity to see that confirmed ‘in the flesh’. Hans Hollein’s line-up of Doric columns (his Strada Novissima, originally made for Venice’s Architecture Bienniale in 1980) left me similarly unmoved, if still glad to have registered it as a material presence. The clever ironies now all look so earnest, overweening and portentous. The claim of postmodern architecture was to recover ‘meaning’ by using historical references, but this populist move just revealed the vacuity of the gesture – its emptiness both as gesture and as historical intervention. As lived experience, so-called postmodern space is scarcely different from that of the buildings and squares it sought to trump. However, the discourse on postmodernity advanced itself not so much through its constructed realities as it did through architectural photography. Images in glossy journals like AD endowed the examples of ‘postmodern architecture’ with optical allure and faux clarity. The exhibition didn’t give us these, but quite a few architectural models, which captivated in another way, returning us to the moment of imaginative projection; to the particular totalising perspective of corporate clients and to the encounter in which the architect attempted to convince them that one grand vision could coincide with another.

Nils-Ole Lund’s The Future of Architecture (1979) was similarly intriguing. Its collagistic fracture was invariably ironed out by the mass circulation of the printed page and then hyped up further and projected by its circulation as a lecture slide. Both reproductions rendered the work into something that looked like a large photorealist painting, albeit one with some uncanny transitions on its synthesised surface. Seeing the original montage, I was struck by just how small it was, but I was mostly caught up wondering how it had even become a coin of postmodern discourse. It’s so clearly possible to have it read otherwise. Its figure of ‘modernity in ruins’ could just as easily be interpreted as picturesque, romantic or surrealist; comprehended not as modernism’s ‘death’, but as modernity itself. (These days, we might note, the figure is much favoured by polemicising pro-modernists.)

Image: Nils-ole Lund, The Future of Architecture, 1979

I came to realise that the cadaver being scavenged was not modernism’s but that of postmodernism itself. Perhaps Jencks’ opening statement approached the status of a larger curatorial conceit? In one of the show’s central rites of passage – its ‘Times Square’ – the exhibition design echoed the mediatised city of Blade Runner; we were taken into that night time world of screens and monitors conjured up so memorably by Ridley Scott, but here it was David Byrne and Annie Lennox who were the ghastly visages bearing down and cynically mocking us. We had only just passed the Blade Runner clips which, in turn, had been placed under remit of ‘Apocalypse then’; all suitably ‘intertextual’. It would be nice to acknowledge such thematic introjection as a piece of curatorial élan; a meta-joke where an object of study became the exhibition’s conceptual motor. Sadly, the pattern of auto-ingestion was too weakly drawn. Instead, what prevailed was a banal subject/object collapse that seemed not to be of anyone’s choosing or staging, but rather the result of a simple failure to maintain critical distinctions or to exercise historical caution.

Certainly, the role of publications (Domus or i-D, etc.) as disseminators of styles was grasped. But there was also too much uncritical acceptance of what had been read in the canonical books promoting postmodernism. Yet the making of ‘postmodernism’ – via this avalanche of secondary literature – is a history in its own right. It was a publishing category tied to the sale of pedagogic shorthands. (In the ’90s, it used to be said – apocryphally, no doubt – that if you wanted to get your book out, you needed the P-word in the title.) There were allusions to The Language of Postmodern Architecture and Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture (primary texts, we might say, and which played their part in the construction of the discourse), but the exhibition’s perspective seemed to have been essentially directed by the mass of generic style surveys produced to support the art and design school curriculum. These synthetic works were reliant on weakly conceived Wölfflin-type schematisations, derived from Venturi and Jencks and shored up by snippets from the heavyweights like Lyotard or Jameson. Studying 3D design? Well here’s how the story goes: Sottsass, Memphis, Studio Alchymia, etc. – irony, pastiche, bricolage, appropriation, quotation. Each segment of the university and polytechnic divisions of labour had its corresponding volumes to enforce and shore up these schema. For all the talk in Postmodernism of deconstruction and reconstruction, of irony and self-awareness, there was little sign that the archive itself had been recognised as form, as institution, as construct or as discursive production – let alone historicised or subjected to critical analysis. The annals were read straight, as direct access to an authentic voice, and then played back.

Image: Venturi, Scott Brown and Associates, Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown in the Las Vegas Desert with the Strip in the Background, 1966

And yet even the archive was strangely limited. What, for example, happened to the central discussion of the ’80s: the distinction between conservative historicist and critical poststructuralist versions of postmodernism? It is rendered by the curators as postmodernism’s ‘theatrical’ and ‘theoretical’ characteristics, its exciting ‘ambivalence’. Yet, at the time, the differences were articulated as sharp political contestations. From Hal Foster’s essays in the ’80s to the architectural debates of the Revisions group in New York, this sense of embattled opposition was expressed explicitly and repeatedly. We can now recognise these as responses to the Reagan administration’s aggressive imposition of neoliberalism. I happen to think there were problems with these left leaning challenges to postmodernism’s mainstream, but they were certainly not just one inflection within the postmodern ambiguity.

Less visible, but implicit in the dates and places – and sometimes in the objects themselves – other stories seemed to lurk; further paths suggested themselves for historical investigation. One friend speculated on the possibility that the Milanese design objects – mostly dated immediately after the repression of the Italian left (the so-called ‘years of lead’) – were symptoms of a ‘Pastel Thermidor’, Italy’s counter-revolution exported and niche marketed. It is tempting to see the pots and kettles as direct symptoms of a new political domination – especially when, like me, you actively don’t like them, and especially when you know whose needs they were designed for – but I suspect their place may well be more complex and contradictory. One would want to consider these human products not merely as semiotic representatives of some idiot ‘ism’, but as material agents within a changing field of social and economic relations. Postmodernism’s veneer of historical analysis relied, however, on media coined buzzwords and soundbites: ‘yuppy’, ‘designer decade’, ‘boom’. History deserves better treatment; so do (at least some of) the objects. The commodities still have their stories to tell. Give the fetishes their due.

Gail Day <G.A.Day@leeds.ac.uk> teaches in the School of Fine Art, History of Art and Cultural Studies at the University of Leeds. She is author of Dialectical Passions: Negation in Postwar Art Theory (Columbia University Press, 2010), shortlisted for the 2011 Isaac and Tamara Deutscher Memorial Prize

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com