No Stars, no Solos – just Sound, Motion, and Energy: an Interview with John Gruntfest

Given the ephemeral nature of improvised music, it is easily forgotten after the performance. Despite that, the work of saxophonist, poet, and musical event organiser, John Gruntfest, is almost criminally overlooked. Stretching over four decades, Gruntfest has played saxophone in a huge number of ensembles, as well as collaborating with political art and theatre groups such as the Pageant Players, the Motherfuckers, Bread and Puppet Theatre and the Living Theatre. His work has varied from small-scale performances to the arranging of immense forums and events for collective improvisation.

Gruntfest led the Ritual Band and Free Orchestra in the seventies and eighties as well as the Free Orchestra’s thirtieth anniversary in 2009, The Raven Free Orchestra. His first albums, Live at Pangea 1 & 2, were voted best improvised albums of the year by Cadence Magazine in 1977. Gruntfest played at the Berlin Wall when it came down in 1989. He was part of the SF punk funk scene in the 80s, playing with The Appliances and touring with Indoor Live, Tuxedo Moon, and Snakefinger. His record label, Independent Records, was one of the first indie record producers of alternative music. He is one of the foremost proponents of improvised and experimental music in the San Francisco alternative music scene

Stevphen Shukaitis recently had the chance to meet up with Gruntfest and ask him about the politics of his art and performances.

Stevphen Shukaitis (SS): How do you understand the relationship between art and politics? Not only in a general sense, but also in the ways that you’ve worked through that relationship in your own practices?

John Gruntfest (JG): It is not possible to live in a world of dualities, dichotomies, dialectics, dissections, interrogation, and analysis. There is only one life and we are it. What is politics but the absence of imagination? What is art but the absence of life? If energy is to be preserved, then we must use fluctuations in the quantum field to create a force that is ongoing, life enhancing, joyous, creative, mind expanding, futuristic, hopeless, all pervasive, transcendent, and yet rooted in the present moment. When one works through the relationship of art and politics, one comes out the other side and finds that there is nothing there. Alone, left to one’s own devices, assume the worst has already happened and take the next step. Jump off into the void and embrace infinite possibility.

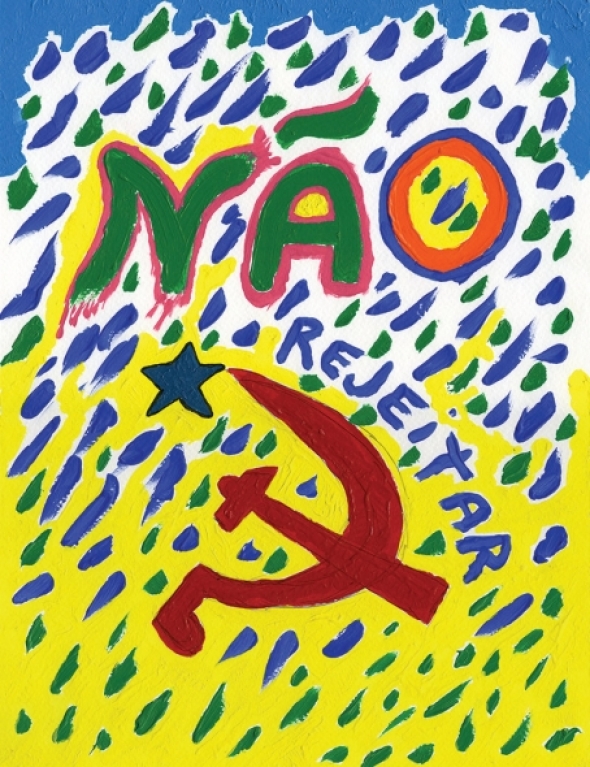

SS: I’m interested in your attempts to recover the images and ideas of Che and the hammer and sickle. What motivates this? What infinite possibilities do you see in that? What do you hope to accomplish by doing so?

JG: There was an idea – an attempt – to create the new woman and man, true revolutionaries whose heart pumped with the blood of love, whose aspirations were built on a love of the people. Che was at that time an embodiment of that new man – our revolutionary hero / anti-hero. And yet, he was someone with all the failings and successes of a man. The Cuban revolution, like so many other revolutions, embodied all the successes, failures and contradictions of human behaviour. But – get this – the health indexes of Cuba are the highest in the Americas, better than Uncle Sammy’s United States. So Che is both hero and anti-hero. Future Che attempts to take the new man-woman to another level where we can live devoid of capital’s strangulations, enchantments, delusions, illusions, contusions: that material cesspool sold to the masses as freedom.

I’m a red diaper baby. I grew up under those images of revolution, communism, socialism, as embodied in the hammer and sickle. During the McCarthy era, that image, those books were hidden in my house. My grandparents, parents, cousins were communists, socialists, even anarchists, although their dogmatism was hard to take and still is. I wanted to free up that image and make it mine, so I began a series of hammer and sickles to focus on revolution, solidarity, internationalism – all those things which we seem to have lost. The PCP in Portugal would chain big signs up in the middle of busy intersections denouncing the bank bailouts, the selling off of public lands, and that was considered a legitimate form of free expression. Signs like that would never last long in the US. So the painting Nao arose out of that desire to have free expression in the most public of places. It is what graffiti wants to achieve but fails to most of the time. We need a collective we to express our disgust for the way things are. So that is it: hammer and sickle – revolution, solidarity, internationalism; all our lost hopes and failures to change the system of capital. Let us give the collective finger to capital with this lost and betrayed image.

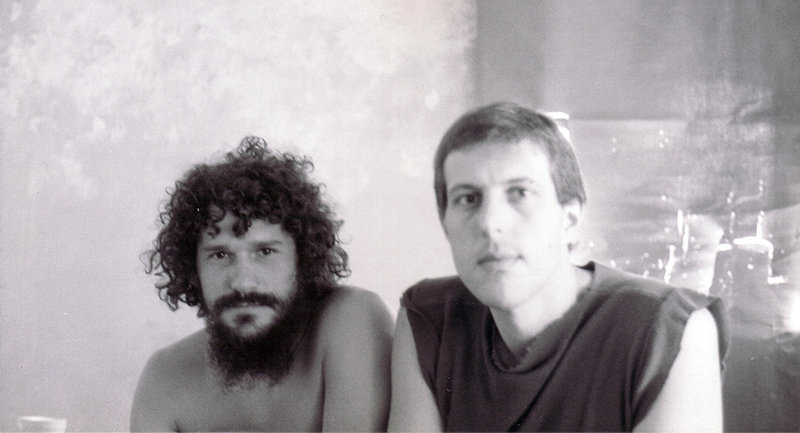

John Gruntfest and Joseph Sabella, 1979

SS: Can you describe the evolution of your work over the past forty years? What has inspired you to change your approach (or not, for that matter)?

JG: Complete dissatisfaction with things as they are, my work as it is. What I have created in the past does not interest me so much as what is happening right now, although I will confess to having some favourites like ‘July 4, 1979’ and Future Che. Always pushing for the new to emerge. There has got to be a way to express something different and new; some vibration that really sets the energy moving, freeing the creative and getting healthier, artistically wealthier, visionarily stealthier. Blasted out of my complacency and examining the minute detail of the complete voidness of my existence. Embracing death as a lover.

SS: How do you understand the relationship between poetry and music? I’m asking as, while you have previously released a number of recordings of your music and the projects you’ve been involved with, it’s not until quite recently that you’ve published any of your poetry.

JG: Chant Incantation Vachel Lindsay Whitman Kerouac Ginsberg Sitwell Yevtouchenko.

The magic of sound rhythm

Trance being into art being into life being

Into being life

Sound magic moving through the body

Healing the body

Hearing the body

We sing of ourselves celebrate ourselves

Jump for joy

Jump and stomp

Pump and grind

Shout flout Fleeing normative confines

Sound and rhythm music poetry

Pulse drive thrive strive

Jive no jive

Flowing growing glowing

Breathing ourselves into being

Raven Free Orchestra in 2009

SS: Can you describe your approach to collaboration and collaborative practices? I’m interested both in the period when you were involved in Bread and Puppet Theatre and the Motherfuckers, as well as the large group improvisations you orchestrated, like the Raven Free Orchestra…

JG: What really knocked me out as a kid was playing in big bands and orchestras. There was an amazing energy to being part of a big sound. Something special happens in a large group when a musical wave of such force is created that it takes folks right out of their bodies (with Count Basie Band Live, you could stand in front of them and feel the force of the wave actually hit you). You can feel the wave in your body. All of my orchestras and big bands have operated on the principles of escape velocity and critical mass. The ecstasy and joy is something that can transcend the moment in the same way that large groups can overcome the limitations of the individual. These events are unpredictable and not repeatable. You set the wave in motion and hope for the best.

One needs willing collaborators. I have been lucky that way since folks have been willing to go for it. As a conductor I try and get into some kind of open state of mind – Buddha Mind – where I am just a vehicle for the energy of the group. Plus there has got to be a willingness to allow folks to feel part of the whole process. The Raven Free Orchestra had energy of its own that no one person could control. People arrived early, began warming up with energy, started early, and finished early. It followed its own pulse, with everyone having a lot of fun.

Being part of radical theatre in the sixties in New York was a wild experience, verging on the out of control much of the time. Things came together on the streets and in lofts. A confluence of ideas, politics, energy, art. I think the one thing we all shared was the fact that we were sick of sitting around in endless political meetings, and theatre was a way of actually taking political ideas to the street. There was a moment when Radical Theatre Repertory formed an umbrella for The Pageant Players, Bread and Puppet, The Living Theatre, Sixth Street Theatre, Mime Troupe, etc. Tours were set up and we actually brought political theatre to colleges from the streets. It was very exciting because things were intense on campuses with the Vietnam War and riots in the streets. But there was so much anarchy that, in a certain sense, it did not last long. The Motherfuckers were having street parades and feeding people, trying to organise the lumpen. Everyone interacted on the streets and in their own special milieus. There was also a lot of friction because all the energies of the groups were so strong. I think that is one of the reasons that it all fell apart. People felt things differently and of course the police repression was very intense. On some level exhaustion set in and folks went on to do their own thing.

John Gruntfest and Richard Gilman-Opalsky at the Raven Free Orchestra performance, 2009

SS: How do you approach large group improvisation? At the risk of asking a very naïve question, how does it work? I’ve seen the Peter Brotztmann Tenet play a number of times (which has been amazing), and asked various members of the group, but they seem as baffled as anyone else how such large group improvisations hold together and develop.

JG: Usually there is some kind of visionary experience where the event becomes clear to me. So in a sense it is the fluctuation in the quantum field where a particle is created in pure space. We could say that the event already exists and all we do is make the spirit-energy manifest in the real world. From profane space to sacred space: Eliade. I like to sketch out a structure with written parts. The community consists of all kinds of players. Some can read, some cannot. Some are technical monsters, some are not. Some have only come to music through electronics and have never touched another type of instrument. Everyone is invited to participate: musicians, dancers, artists, poets. Who shows up is always a surprise. Since these are one-time events we usually play through the piece in the afternoon and then do it again at night. That is it. And then it is gone…

You really need willing comrades, collaborators and partners. I have been lucky because the folks who participate really want something special to happen. There is a real willingness to go for it all together. It is why these events are not repeatable.

There is also a certain kind of democratic equality to my conducting: no stars, no solos – just sound, motion, and energy. Waves emerge and submerge. No one can dominate what is happening because folks are really focused on the group effort to create something greater than the whole; overcoming the limitations of the individual and making something hopefully more profound which is only possible in these large ensembles. The wave dominates and, with harmonic interaction, sounds are created that no one person is making. So when I conduct I try and get out of the way and just feel the energy that is happening, letting it rise and fall, respecting all the players involved.

Raven Big Band Buddha Mind Ensemble

SS: What’s the influence of Zen Buddhism on your playing and art?

JG: Breath is such an important part of how we live and play. You could say it is the centre of our music, art, dance and poetry. Mindfulness. Paying attention moment to moment and not getting lost in the endless babble going on inside and outside of us. The internet is a perfect example of this babble: Facebook, Twitter, etc. I have a song that has two simple lines: “My mind is working overtime / My mind is working overtime.” How many minds are working overtime? So we take a breath to relax and play. Capital wants our attention all the time, waking and sleeping. It is a little problematic, wouldn’t you say?

Da Buddha mainly talks about how the mind works if you read the sutras and I do not like the idea of turning his teachings into a religion. He was a philosopher, after all, and a rebel. “All things are manifestations of mind.” What does this mind of ours do? It discriminates and then gets attached to its discriminations. Think of capital and how it discriminates. Profit is good, equitable distribution is bad. Competition is good, co-operation is bad. And on and on, such that the system of capital has discriminated to such a point, and people are so attached to those discriminations, that nobody has a clue as to what is real. So we attach ourselves to our discriminations and go on consuming and destroying the ecology.

SS: Can you explain the importance of waves for you, particularly in how you’ve developed an entire person of ‘Wave Man’?

JG: Sound is a wave. Each sound is a complex of harmonics. The harmonic series. Very early on I wanted to play the saxophone in a fully harmonic way just utilising the harmonic series. I wanted to create music based simply on harmonics. ‘July 4, 1979’ and ‘The Greater Vehicle’ are both a realisation of this approach. The music is fully harmonic on the saxophone and ‘The Greater Vehicle’ utilises the harmonic series off of the B flat and C bottom notes of the alto saxophone. ‘Free Orchestra’, from 1979, is harmonically built on concert D flat and concert D, before moving to the Venda ocarina duet, which is a particular Venda rhythmic harmonic music.

Here is the rub. If string theory is correct, then everything is built on vibrating strings that move up a certain harmonic range. Discreet energies, as in quantum mechanics. So we live in a harmonic universe (read some of the Sufis). Everything is built on vibrations. Strings and sounds moving up the harmonic series, creating all there is in the multiverse.

In 1987 I was forty years old and had lost a certain feeling for the music, a certain energy. So I began to surf. Surfing gave me back that feeling that was lacking in my music and reinvigorated my playing. It also made me stronger physically and taught me an essential truth: “You’ve got to paddle out if you want to catch the wave.” Sometimes there is a lot of paddling out before you can catch the wave. So arose Wave Man, that is the literal translation of Ronin.

SS: Last year I interviewed free jazz saxophonist Joe McPhee and was struck by his comment that, while he would often play New York, London, and Paris, there are very few places around his home in upstate New York where he can or wants to perform. I was thinking about that when I heard you comment earlier this year that you remain rather marginal even in the Bay Area music scene. How have you dealt with this position of marginality? How has it affected your playing?

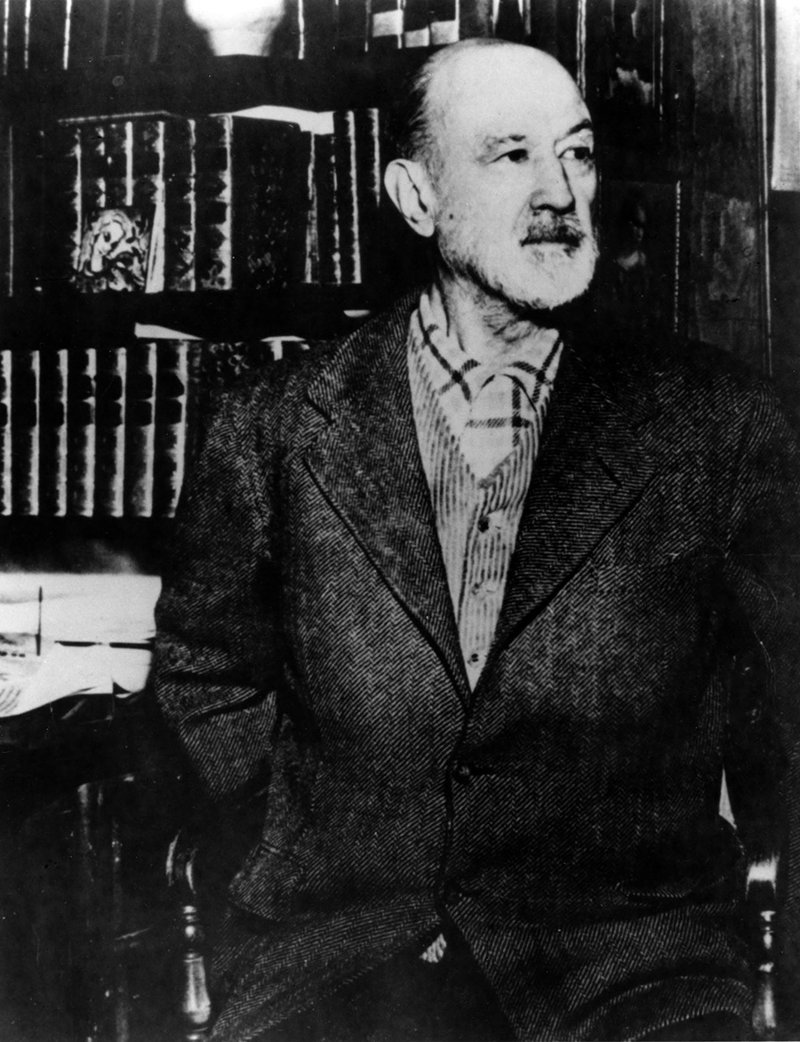

Charles Ives

JG: I came off the road in 1982 after travelling with bands like Indoor Life, Tuxedo Moon and Snakefinger. I experienced the total corruption of the music business and knew that it was no way to make a living. I had also just read the biography of Charles Ives, the great American composer of the twentieth century, who worked during the day and composed at night. So I went to work and separated my music and art from any monetary concerns. I was finally free to do exactly what I wanted to do. It was the best decision I ever made and it also allowed me to help take care of my family instead of being a starving artist. I could also produce the events and music I wanted to because I had an income. Charles Ives was my inspiration in business and in music. He was also marginalised and ignored in his lifetime. The bottom line was that my comrades and I had a lot of fun doing what we did, even though there was almost no money or recognition in it. Actually, I feel very successful artistically because I created what I wanted to create without having to deal with the bullshit world of capital and fame. As Johnny Rotten said, “Fun, doesn’t anyone remember fun?”

SS: Speaking of fun, how do you see the relationship between psychedelic culture, music and politics? It seems that at times the relationship can have a politicising effect, like around John Sinclair, the MC5 and the early days of Fifth Estate, but can also lead to a dropout culture of disengagement.

JG: Look, psychedelics or any form of experimentation with alternatives to the status quo was and is important. But it is also important to stay healthy and maintain one’s equanimity. Dropping out, dropping in – it is all OK. We must learn to live in capital and yet not live in it at the same time. Not to be a slave to capital. We must create alternatives to this corrupt and diseased system. Health is important. Alternative modalities are very important. I studied homeopathy and helped to create veterinary clinics with alternative modalities: acupuncture, herbs, chiropractic and homeopathy. Alternative art and music. Alternative life styles. Different ways of viewing things outside of this spectacle. Even though my generation and my parents’ generation failed to change the system of capital, we did create some useful alternatives: holistic health care, organic foods, etc. There are still a lot of alternative venues for music and art outside of the mainstream pop culture bullshit. So it is important to create alternatives in whatever way we can. It is really important not to give up creating the things you really believe. Forget the money, forget the profit. Have fun.

Stevphen Shukaitis <stevphen AT autonomedia.org> is Senior Lecturer at the University of Essex, Centre for Work and Organization, and a member of the Autonomedia editorial collective. Since 2009 he has coordinated and edited Minor Compositions (http://www.minorcompositions.info). He is the author of Imaginal Machines: Autonomy & Self-Organization in the Revolutions of Everyday Day (2009, Autonomedia) and editor (with Erika Biddle and David Graeber) of Constituent Imagination: Militant Investigations // Collective Theorization (AK Press, 2007). His research focuses on the emergence of collective imagination in social movements and the changing compositions of cultural and artistic labor.

Images: except Charles Ives all images John Gruntfest

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com