Communities at the front-line of coal extraction

Communities at the front-line of coal extraction

“Mining is going on a hundred meters away. When they started blasting, all the dust was brought to our vegetable gardens. Vegetables got covered with the coal dust which is impossible to wash out. Now I don‘t want to harm myself by eating anything from this garden,” a resident of Kazas, Siberia, Russia, describes the impact of coal mining.

These are just some of the impacts on the indigenous Shor people of the UK's addiction to coal. The UK imports two thirds of the coal it burns in the remaining nine coal fired power stations. In 2015, 24% of our electricity came from burning coal.

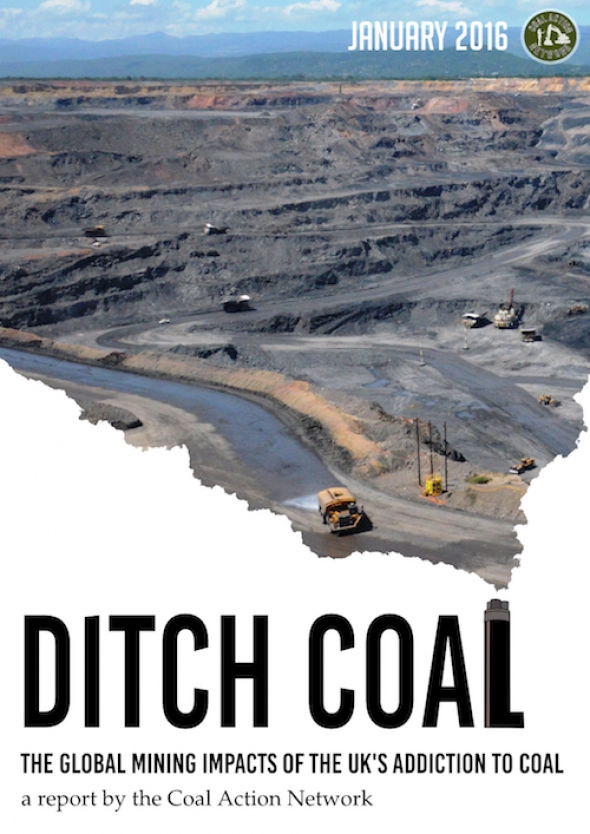

Ditch Coal, a new report from the Coal Action Network released earlier this year tells the human and localized environmental story of the coal burnt in UK power stations. The climate change impacts of burning coal are well documented, but somehow hard to relate to in a concrete manner. By contrast the stories of those living in the shadows of the mines are somehow more tangible, being direct human experiences being felt already.

The Siberian village of Kazas was surrounded by opencast coal mines and had a population of predominantly indigenous Shor people. Kazas was entirely destroyed in 2014 to make way for the expansion of the mines although the villagers did not all consent to leave. The problems of this village are not unique. For each tonne of coal produced six hectares of land is disturbed, land which was home and habitat to both people and wildlife before the mining companies' encroachment.

Prior to the destruction of Kazas, pressure was applied to get families to move. Infrastructure was no longer maintained – roads were not cleared of snow in winter and clean drinking water was no longer provided. With only 6% of water from the mines being treated, filthy water killed the fish and the wildlife dispersed, preventing the traditional economic activities of the Shor people - hunting and fishing.

A Russian anti-coal activist is visiting the UK for a speaking tour starting on the 25th May in Brighton and finishing on the 10th June in London. He will discuss the problems caused by mining for the UK’s power stations in his home country, while the Coal Action Network discuss how we can act to reduce the destruction.

Communities in the coal mining regions struggle to have their objections heard as the system is stacked against them. Decisions about mining applications are heard away from the ancestral lands which are threatened so those affected cannot attend hearings.

The spirituality of the Shor people has been totally disregarded, with Karagay-nash mountain being desecrated and destroyed by mining. For the inhabitants of nearby Kazas, the mountain was considered the seat of an extraordinarily powerful spirit which protected Kazas and guarded their lives from birth to death.

The worsening situation for the residents meant that many agreed to leave. For those who didn't the outcome was more sinister, their homes were destroyed by arson.

The village of Kazas now only exists in the memories of the people who lived there. “Chuvashka is the Shors' only village in this area. In the 1990s, about 16,000 Shors were living here. Today, there are just between 4,500 and 5,000 people here” said a Shor woman in Ecodefense's film Condemned. Eight other villages in the area have been destroyed.

The mining exploits in the Kemerovo region have left many of the indigenous Shor homeless, or displaced to other areas, which severs their spiritual, cultural, and practical attachments to the land. No adequate substitute land, nor compensation has been offered to them. The Kemerovo Oblast, where most of the Shors and Teleut live, produces 60% of Russia's coal for export.

A similar story is told by the Teleut people also living in the Kemerovo Oblast. “Once the Teleut language disappears the nation disappears” said Maria Kochubeyeva, president of the Association of Teleut People. The language of the Teleut is predominantly spoken in rural areas, so they are threatened with being lost entirely, as displaced villagers seek new accommodation in cities. The Teleut are also being displaced to make way for coal mining expansions, but there is less information detailing their plight.

The Russian coal industry also has the most dangerous working conditions of any industry in terms of risk to life and welfare, with 40-50 fatal accidents each year, killing 180-280 people annually, mainly in the deep mines.

Why is the UK burning Russian coal?

In the year to August 2015, 31% of all thermal coal burnt in the UK came from Russia. Since 2005, Russia has supplied the UK with more coal than any other country - coal is cheaper from Russia than anywhere else, which is why we burn so much of it. There is little transparency in the coal supply chain and large volumes.

Mining in Colombia

Colombia is known for its human rights abuses, yet it supplies 23% of the coal imported to the UK. Over 90% of Colombian coal production occurs in three large-scale open cast mining operations in the northern departments of La Guajira and Cesar. Communities close to the mines suffer the same problems in terms of forced relocations as those neighboring Russian mines, additionally there have been links made to assassination attempts on those who speak out against the mines, mass killings and violence.

The Dark Side of Coal, a 2012 report by Dutch NGO PAX, draws together testimonies from ex-paramilitaries, ex-employees of the mining companies, victims of the violence and human rights lawyers .

Hernando Figueroa Pallares has evidence of Drummond dumping 500 tonnes of coal at sea after problems with a barge transferring coal to an international ship. He planned to go to the authorities about the incident, but before he did an assassin came after him, thought to have been sent by the coal company.

As Hernando describes it, “he was in the entrance of my house with a gun in his hand [...] He came out in to the yard but he didn't see me because it was dark. He had the gun ready. I thought if I leg it he is going to kill my wife, so I decide to see what God's will is. Without my shirt on, I shout and run at him. The first bullet enters me in the lung.” Hernando was lucky to survive although he still lives in hiding. Many others have been killed in similar incidents.

Protests against the mine's expansions and pollution by local people have been harshly put down. In 2007 in La Jagua de Ibirico, Cesar, violence was carried out by the police against local people. “For several years [we have] been suffering from contamination produced by mining operations and transport of coal from the mines of Glencore A.G. and Drummond, and from unemployment, pulmonary illnesses of children, poverty and the military-paramilitary presence which has accompanied the arrival of the transnationals and which has produced grave human rights violations. Because of this, two days ago the residents decided to carry out a peaceful protest to block the roads which enter and exit the town.

Today, in an act of savagery characteristic of a fascist regime, the riot police violently attacked the march, murdering Manuel Celiz Mendoza, aged 42 years,” read a civil society statement released on the day of the attack. Seven other people were critically injured including a two month old baby.

The three main Colombian mines are run by private companies which means there is the potential for more transparency allowing coal to be traced from its point of extraction to the power stations burning it than in Russia where a myriad of small companies combined with State opacity make this much more difficult. However the companies burning this coal, where they do show some commitment to transparency, do not seem to genuinely display supply chain transparency nor attempt to alleviate the problems caused.

The voluntary industry initiative Bettercoal was been set up by companies in response to human rights violations and environmental damage in the coal supply chain. Yet the Bettercoal Code does not require individual member companies to provide transparency on the mines from which they source their coal, nor on their business partners in the supply chain. Bettercoal intends to audit the mines, but will not make the information publicly available.

Mining coal in the Global North

In the USA communities are fighting back against coal mining. The Obama administration is slowly closing power stations and claiming that this is helping to reduce greenhouse gases. However, it is also supporting business to find export markets for the same coal, contributing to global warming through burning the same coal plus additional harm caused by its long distance transportation. 14% of coal burnt in the UK comes from the USA.

Ditch Coal shows how disadvantaged communities such as those living at Ironton near New Orleans can fight coal infrastructure and win. RAM terminals wanted to build a coal export terminal to add to two others within five miles, an oil refinery and a oil tank farm. Local people stopped the application. "Preserving the unique history, heritage, and natural resources of places like Ironton, Gretna, and our coastal marshes over the short-sighted interests of an out of state coal company is something that we can all agree on. We are glad to see that the district court agrees" said Devin Martin, an organizer with the Sierra Club.

Elsewhere coal companies have been forced to reduce water pollution. Between 2012 and autumn 2014 Alpha, a major USA mining company, was served with or expecting 12 lawsuits against many of its subsidiaries. They have been found guilty in at least four cases, so far.

Most of the coal coming from the USA to the UK is from damaging longwall mining systems - where the material over the coal is intentionally collapsed as the mine progresses - or from opencast or mountaintop removal mines. Both of these methods destroy huge areas of land, displace people and damage the water table. During mountaintop removal coal mining is destroying entire mountain ranges in Appalachia. Here communities are organizing against the continuous mine applications and fighting for justice for places already affected. The impacts on humans and biodiversity are severe, with water pollution causing increased rates of cancer and an ever present threat of dams cracking and flooding land.

Mining companies in the USA have recently struggled with falling international coal prices and reduced domestic demand. Peabody, the world's biggest private coal company went bankrupt in April 2016. It is the most recent in a line of big companies to fail.

Mining in Britain

32% of the coal used in the UK is extracted in Britain in the year to September 2015. Here opencast mining operations have continually faced resistance from those living in the shadow of mines and proposed sites. There have been protest sites occupying land to slow work on mines and in advance of applications being approved. At present there are 21 opencast mines working, a number which has begun to decrease.

Communities in northern England, central Scotland and south Wales have been fighting against opencast mines since it became clear that mine companies wanted to cheaper opencast methods. Local people are fighting against destruction of their landscape, increased HGVs on the roads, light and dust pollution, and the countryside being replaced with vast black holes which create little meaningful work.

“In the '80s we were dependent on coal, but it left us and we have adjusted to that, in a way, 30 years down the line. [...] We have never recovered around here, the only recovery is nature,” Lynda Clarkson, No Opencast Varteg Hill. Many of the people fighting against opencast once worked in the deep mines, they see the opencast mines as destroying their communities assets and increasing rural poverty and ill health.

There is a democracy issue around the UK's mines. Mining companies refuse to listen to local people and the councils which represent them. In recent years there have been several appeals. “The developers paid rooms full of people to write thousands of pages of technical documents. We had to read them, research them, understand them and respond to them. All while doing our jobs and

trying to live our lives around it.” Eddy Blanche, United Valleys Action Group. The impacts if mining is permitted are much worse.

At present the market for British coal is weak, due to low international coal price and resistance from communities disrupting mining companies flow between sites. This means that there are a dozen sites which have been approved but not yet started and while other sites have been abandoned.

The biggest mining company in the UK Scottish Coal, folded in 2013 and ATH Resources followed shortly after. UK Coal - once England's main mining company - liquidated when its last deep mine, Kellingley, closed in December last year. Coal mining in the UK is a dying industry.

There have been many sites in Scotland and Wales which have been abandoned after coal was exhausted or the companies went into liquidation. As a result these vast holes are filling with toxic mine water and pose public and ecological hazards. Local communities are now fighting for sites to be restored, but the companies either no longer exist or have sold their assets to shell companies who do not have the funds to complete restoration. As a result the clear up will fall on the public purse.

In wales a 2014 report for the Welsh Government found that of the ten active sites five of the the larger sites may have insufficient bond cover at some stage of their operating life. The biggest opencast mine in the country, Miller Argent's Ffos-y-Fran is thought to have a potential shortfall of £35 million as it will require significant earth moving of overburden mounds to restore the site.

When Scottish Coal and ATH resources went into liquidation the holes they left behind could

not be filled with the money available in the bonds. In 2014 there were thought to be up to 20 unrestored opencast sites which had belonged to these two companies. Since the collapse of these companies East Ayrshire Council alone has been left with a shortfall of £133 million to restore sites in their local authority area.

The Coal Action Network call on the government to legislate against coal mining which would be in line with a 2025 coal phase out.

What is the solution?

Ditch Coal calls on the UK government to close the remaining nine coal-fired power stations as soon as possible and for decisive action - including a complete and legally binding coal phase out - as soon as possible, together with an enforced ban on coal mining in the UK.

Coal Action Network believes that real change is not brought about by asking the government to make changes for the better. We believe that we need to take action now to support communities whose livelihoods are being destroyed in order to "keep the lights on." There are plenty of ways that concerned people can get involved. Whilst international solidarity is key, supporting residents in our own country who are campaigning against coal mine applications and fighting for better restoration of abandoned sites is just as vital. Coal infrastructure spans much of Britain and there are plenty of sites to take action, protest and put pressure.

CAN does not believe that simply changing the source of coal from one region to another, nor from one company to a 'better' one will bring about the change required. The only way ahead is to fight for a fast coal phase out by whatever means we have available, be that divestment from companies involved in fossil fuels, lobbying or direct action.

We simply cannot operate on a business as usual principle and merely change from one environmentally damaging system to another. We need to radically re-think our energy system.

We must move away from our reliance on damaging extraction processes and the relentless exploitation of finite resources. Change must be founded on the principles of a serious reduction in demand for and production of energy, a reclaiming of decision-making power from the vested interests of energy companies to local communities, and solidarity with communities impacted by energy infrastructure. It is time to ditch coal for good.

www.facebook.com/pages/The-Coal-Action-Network/429...

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com