When the Streets Run Red: For a 21st-Century Anti-Lynching Movement

The heterogeneous elements of the Black Lives Matter movement are fighting white supremacy by confronting gendered domination, capitalism, and the repressive apparatuses of the state. Erin Gray traces the critical impulse of the current movement against anti-black violence to the legacy of Ida B. Wells’s radical anti-lynching campaigns, and suggests that the fiercest opposition to police terror in the US has always been against the law

Our country's national crime is lynching. It is not the creature of an hour, the sudden outburst of uncontrolled fury, or the unspeakable brutality of an insane mob. It represents the cool, calculating deliberation of intelligent people who openly avow that there is an ‘unwritten law’ that justifies them in putting human beings to death without complaint under oath, without trial by jury, without opportunity to make defense, and without right of appeal.

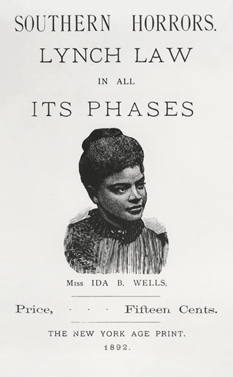

– Ida B. Wells, Lynch Law in America [1]

Shortly before the 2014 winter solstice, the US witnessed a ‘wave of indignation’ whose members took to the streets to demand a system-wide response to police attacks on black lives across the country. [2] This wave crested on Saturday, 13 December, as thousands of bodies and voices coalesced in major cities across the US and internationally for a day of action dubbed ‘the Millions March’.

In the San Francisco Bay Area, as factions from different parts of the bay converged at the Alameda County Courthouse in Oakland for a speak-out organised by UC Berkeley’s Black Student Union, word spread that pictures of black men hanging from nooses had been discovered that morning at Cal. Hushed and angry murmurs cut through the crowd as folks chewed on the possibility that local white supremacists might have sought to spectacularise racist terror on a national day of resistance to anti-black violence. The lynching cut-outs found hanging in front of Sather Gate and near the Campanile at Cal were blown-up reproductions of photographs of Laura and L.D. Nelson, who were brutalised and hanged over the North Canadian River by a mob of white men in Okemah, Oklahoma in 1911, after Oklahoma deputies confronted the Nelsons in their home about a property dispute. [3] Printed across the blown-up photographic cut-outs were the victims’ names, along with Eric Garner’s last words, ‘I can’t breathe’.

To make Laura and L.D. Nelson present in the space of Garner’s dying breath is to render a cut in the reigning ideology of historical progress, which mistakes current police and vigilante violence against black Americans for a stunning aberration from colorblind democracy, rather than the normal workings of late liberal lynching culture. Like Garner, the Nelsons were harassed by the law for defending themselves against the immiseration that stems from capitalist relations of production. Oklahoma deputies confronted the Nelsons for stealing a cow to assuage their hunger, while Staten Island police murdered Garner for selling loose cigarettes to make ends meet. In both instances, the law and its pale-faced auxiliary sanctioned lethal extra-legal violence in order to protect the interests of white capital.

Image: The lynching cut-outs at UC Berkeley.

Image: The lynching cut-outs at UC Berkeley.

The cut-out action at Cal was an unambiguous act of protest calling out the relationship between the history of mob violence against African Americans and the history of policing in the US as structurally bound to the racialised relations of dispossession and pauperisation that characterise US capitalism. [4] It reminds us that when we demand justice for Eric Garner we are also demanding justice for the thousands whose lives were ended or otherwise destroyed by US lynch law. It recalls the names and faces of people whose deaths have not yet been fully mourned, and includes current victims of police and vigilante brutality in the historical tally of US lynching victims. Most importantly, it looks back on the historical character of anti-blackness in the US as well as the rich tradition of 19th- and 20th-century radical anti-lynching praxis, as the current movement against state-sanctioned anti-black violence moves into 2015.

Generating a Feminist 21st-Century Anti-Lynching Movement

The decision of the anonymous artist collective to enlarge and display George Farnum’s photograph of Laura Nelson – the only known photograph of a female lynching victim – reiterates the need for a feminist analysis of anti-blackness and of the state apparatuses that normalise its most violent machinations.

Historian Paula Giddings recently argued in The Nation that the continual assault on black life by police and vigilantes must be met with a 21st-century anti-lynching movement that recognises the impact of white supremacist terror on all black people – not just the black men whose spectacular killings so frequently become iconic fodder for racial justice movements. Giddings forwarded two specific demands: 1) that we mobilise the historical memory of lynching responsible for the outraged response to Darren Wilson’s execution of Michael Brown and to the sight of the slain teen’s corpse rotting in the street for several hours following his death, and 2) that our mobilisation be an unflinchingly feminist reactivation of the lessons of anti-lynching defence campaigns rooted in the intersections of racial and sexual violence against all black people. [5] The only way to end violence against all blacks, Giddings proposed, is to activate a 21st-century anti-lynching movement inspired by Ida B. Wells’s feminist anti-lynching praxis in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Giddings began her piece by setting up a mirror between the 1890s and today: while black people seem to be doing ‘better than before’, conservatives are curbing our access to the vote, many of us are under the control of an ever-expanding criminal justice system, and we are being killed at alarming rates both judicially and extra-judicially, with perpetrators of anti-black violence being given institutional impunity. As in the 1890s, the spectacular deaths of black men overshadow the forms of violence experienced by black women and LGBTQ people. And like the late 19th century, we are told that accommodating the capitalist ethics of hard work and heteronormative respectability will, over time, result in our betterment.

This is the logic of the White House program My Brother’s Keeper (MBK), which aims to close the US’s racialised ‘opportunity gap’ by devoting $300 million to help black boys achieve the dream of middle class assimilation – by demystifying racial stereotypes, introducing boys to ‘successful’ men, and providing them with job training.

MBK reifies poverty and violence as men’s issues. Giddings not only cautioned against martyring young black men without acknowledging the violence that underwrites the experience of being a black woman in the US; she reminded readers that the ideological justification for killing black men is structurally dependent upon the degradation and vilification of black women. [6] By refusing to acknowledge the devastating effects of racialisation on young women of color – that we are targeted for bodily punishment by intimates and police at rates dramatically higher than are white women, that we are failed by public education, that we are abandoned to economic blight – MBK has a more insidious consequence than mere myopia: it perpetuates a demoralising and demobilising vision of ‘black boys and men’ as separable from the other black people in their lives. It perpetuates a misogynist episteme which tells us that violence directed at black boys and men occurs not in spite of black women but because of black women. [7]

MBK is modeled on the same kind of ideological framework that was codified as public policy in the wake of Daniel Moynihan’s The Negro Family: The Case for National Action in 1965. The Moynihan Report argued that black poverty stemmed not from centuries of white theft but from a black propinquity to vice that has been the result of a culture of pathological black mothering. But as Angela Davis argued in ‘Reflections on the Black Woman’s Role in the Community of Slaves’ – her 1972 magisterial take-down of the Moynihan Report – the tendency to finger a mythic black matriarchate that stretches all the way back to slavery as the root cause of black poverty and the so-called emasculation of the black family is an ahistorical and misogynistic fallacy. At the core of this fallacy is the supposition that black women collaborated in their enslavement and in the enslavement of their peers.

Davis refuted the Moynihan Report by reminding readers that for a black matriarchate to exist under slavery was a structural impossibility. Drawing analytic attention to the institutional rape of enslaved women, and describing this state-sanctioned sexual terrorism as a form of counter-insurgency aimed at quelling everyday modes of slave resistance, Davis argued that black women have historically been ‘custodian[s] of a house of resistance’, guarding and cultivating revolutionary practices of black survival. ‘Without consciously rebellious black women, the theme of resistance could not have become so thoroughly intertwined in the fabric of daily existence,’ Davis wrote. ‘The status of black women within the community of slaves was definitely a barometer indicating the overall potential for freedom.’ [8]

The same can be said of the status of black women in their communities after emancipation. The intellectual and organisational labour of black feminists like Rosa Parks and her sisters in the NAACP – who had engaged in decades-long support for women targeted by sexual violence long before Dr. King stepped on the scene – provided the mass base for the Mississippi Bus Boycott. [9] As in past movements against structural anti-black violence, black women are today leading the most resolutely strident and politically nuanced actions against police and vigilante terror. [10]

Though black women in the US have historically been at the helm of racial justice movements, MBK refuses to acknowledge that the wellbeing of black men and boys depends upon the health of their sisters. It thus tacitly perpetuates the idea that black women pose a fundamental threat to black masculine power while also upholding a dangerous gender binary that ignores the differential forms of violence experienced today by black women and black trans people. [11] Giddings insightfully advised us to question the masculinist individualism and implicit misogyny driving initiatives like MBK, by recalling and reactivating the kind of intersectional vision forwarded by Ida B. Wells’s anti-lynching campaigns in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Ida B. Wells’s Radical Anti-Lynching Critique

Wells was a dynamic educator, a relentless and biting muckraker, and an inveterate advocate of black self-defence. She began her anti-lynching campaign in 1892 after her friend Thomas Moss was lynched in Memphis alongside his colleagues Calvin McDowell and Will Stewart for defending their People’s Grocery Company against an armed attack by white economic competitors. After they were shot and abandoned on railway tracks at the edge of Memphis, Wells realised that lynching had more to do with white social and economic power than it did with rape, which had become the usual justification for lynching.

Three decades after blacks had begun to reconstruct the postbellum South by participating in formal politics, establishing schools, and organising alongside white allies for labour justice, white supremacists sought to regain political power by refiguring black freedom as ‘domination’. Black power, after all, upended the white right to property that hinged on black exclusion. And because women are marked in patriarchal capitalist imaginaries as the carriers of culture, black power was assumed to encompass the social right to marry white – and thus to overturn the white right to property primarily figured in the form of white female flesh. Post-Emancipation southern Democrats, faced with a newly entrenched Republican voting bloc, discovered that sexual metaphors highlighting white masculine authority over public and private property were more effective in reinforcing white solidarity at the polls than were ordinary political campaigns. [12] The ideological conflation of private and public power united white southern men across class lines. With ‘Negro domination’ embodied in the form of the black rapist, white supremacists secured widespread support for their attacks on those members of black communities who refused to acquiesce to their subjugation.

|

| Image: Ida B. Wells with Thomas Moss's family. |

After the lynching of her friends at the People’s Grocery Store, Wells began a four-decades-long campaign to shine a light on US lynch law as the primary mechanism through which white supremacists – with the support of their allies around the nation – maintained a monopoly on health, wealth, and freedom. In her reports for her Memphis newspaper, The Free Speech, as well as in her political pamphlets and the speeches she delivered in the US and the UK, she tirelessly demonstrated that the lynching-for-rape discourse that pervaded most conservative and liberal discussions of lynching in the fin-de-siècle US was based on anti-black racism, toxic Victorian gender norms, and rumour rather than fact. Wells’s writings exposed the fact that black people were lynched not for sexual impropriety but for posing a threat to the white social right to ‘health and happiness’, to white political control of the ballot, and to a white monopoly on capital maintained through the super-exploitation of black prison labour.

Wells also consistently highlighted the sexual double standard that pervaded the South: that white men could systematically engage in sexual attacks on black women with impunity, yet subject black men to unthinkable tortures for engaging in consensual relationships with white women. She was careful to highlight lynchings of black girls and women, and she closed her 1892 pamphlet, Southern Horrors, on a note of outrage at the lynching of a 13 year-old black girl named Mildey Brown.

Lynching is often assumed to have been a masculine experience mediated by the desire for, and the exchange of, white women. But we cannot understand the postbellum discursive network in which lynching spectacularised and fortified a Manichean division between ‘black’ and ‘white’ without analysing the engendering of black femininity. Not only did white supremacist ideology sanction white-on-black rape because of the prevailing belief that black women were sexually promiscuous; it commonly targeted an illicit black femininity as the originating cause of black men’s alleged concupiscence. [13] In conservative news stories and anti-miscegenation propaganda, as historian Hannah Rosen notes, ‘black women were accused of lewd public behaviour, openly promiscuous sexual relations, a supposedly incurable tendency toward prostitution, and, implicitly, a refusal to be subordinated to patriarchal control within families.’ [14]

Race propagandists from the Ku Klux Klan to Daniel Moynihan have argued that black sexuality is inherently illicit and that evidence of this lay in the disorganisation of black family life. But, in truth, a white supremacist episteme that only confers citizenship to members of kin groups organised along bourgeois patriarchal lines has rendered black families, and thus the people in them, illegitimate.

White supremacists continued to systematically rape black women in the wake of emancipation in order to terrorise their communities and bar them from citizenship. [15] In 1871, black women went before Congress to testify to their sexual brutalisation at the hands of the KKK who had raided their homes during the Memphis Riots of 1866. [16] Testimonies by Frances Thompson, Lucy Smith, Lucy Tibbs, Cynthia Townsend, and Mary Jordan recount Klansmen (some of whom they recognised as disguised policemen) breaking into their homes to demand food, weapons, money, and sex before setting the women’s houses on fire. [17] These domestic raids scripted black people as sexually available and subservient to the demands of white men. In Rosen’s words,

White-on-black rape in this context simultaneously embodied and dramatized a larger gendered discourse of race. White men forcing black women to engage in sex and creating circumstances under which black fathers and husbands could not prevent the violence against their family members enacted white fantasies of racial difference and inferiority. Black men and women were forced to perform gendered roles revealing a putative unsuitability for citizenship. [18]

Liberal ideology privileges voluntary submission to labour and marriage – and to specifically male-headed arrangements of labour and marriage – as the cornerstone of modern capitalist citizenry. [19] But white supremacists barred many freed African Americans from forming normative domestic and social relationships and then framed this prohibition as a racial difference rather than the contingent result of labour control and the criminalisation of ex-slaves’ political rejection of a stultifying liberal social contract. Insofar as black people were barred from stable home lives unmolested by gratuitous violence, they were imagined and forced to occupy virtue’s criminal opposition.

Black women’s experiences of being racialised and gendered according to a logic of sexual dishonour were akin to their brothers’ experiences of being racialised and gendered as a criminal class. After the Civil War, southern white landowners mobilised the loophole in the 13th Amendment that makes it lawful to enslave a person who has committed a crime. This, combined with the adaptation of the Slave Codes into the Black Codes, codified rich whites’ continued access to a super-exploitable labour force. The Black Codes criminalised black unemployment, prohibited blacks from working in the skilled trades and from working for non-whites, and forced formerly enslaved women to labour in landowners’ fields rather than for the sustenance and growth of their own families. As Gerda Lerner writes, the landowning oligarchy made it a crime for freed families to organise their labour ‘along patriarchal lines, with men working for wages and women working at home. Any appearance of a household economy organized around gendered and generational divisions of labor, or even a physical structure, a house, that might facilitate a private home life independent of white oversight, was forbidden.’ [20]

The Black Codes, like the Slave Codes before them, did not differentiate between formerly enslaved men and formerly enslaved women: all black people were framed in the eyes of the law as a potential threat to be contained by the prison of labour, and all white people were charged with policing this threat. [21] Sheriffs picked up men and women who transgressed the Black Codes, branded them as convicts, and leased them out to private planters or to their counties to build railroads, mine coal, pave roads, lay brick, and labour in forest industries. [22] Police, ex-Confederate soldiers, and lay white folks also enforced the Black Codes throughout the South. Though the Black Codes were partially mitigated by the passage of Radical Reconstruction laws that sought to integrate southern race relations into free labour principles, they remained a de facto aspect of southern life after the demise of Radical Reconstruction and the violent redemption of the political power of the planter class in the 1870s. As John L. Spivak detailed in his report on Georgia chain gangs for the Labor Research Association in 1934, sheriffs continued to act as planters’ foremen, ‘recruiting and driving labor for [them] wherever it is required’. [23]

Black people were subject to lynch law when they refused to adhere to the Black Codes of the Reconstruction era and to the Jim Crow laws of the New South that succeeded them. Lynching served to prevent black socioeconomic autonomy, and it was Wells who first articulated the ways that so-called extra-legal violence, serving as it did as a weapon of political-economic control, was a supplement to the law rather than its negative limit. Lynching was effectively a para-legal supplement to the Black Codes, and its gratuitous violence served as a generalisable threat to enforce involuntary labour in the wake of Emancipation. [24] Wells crucially demonstrated that there were multiple kinds of ‘law’ operating in the US, and she spoke of the imbrication of the Black Codes and lynch law when she argued in ‘Lynch Law in America’ that capitalist ‘fortune-seekers made laws to meet their varying emergencies’.

In her unfaltering attention to lynching’s inextricable ties to capitalist social relations, Wells grounded her analyses of anti-black violence in the full national scope of anti-black racism. In The Reason Why, Wells situated lynching within the politics of disfranchisement, the repeal of the Civil Rights Bill, segregation, and the convict lease system. ‘The mob spirit,’ she wrote, ‘has left the out of the way places where ignorance prevails, has thrown off the mask and with this new cry stalks in broad daylight in large cities, the centers of civilization, and is encouraged by the “leading citizens” and the press.’ [25] Wells was careful to point out that lynch law was not the result of impassioned, irrational, and local mob forces, but rather the logical outcome of an economic system structured around exploitation and domination. Lynching, she argued, was not ‘the unspeakable brutality of an insane mob’, but rather ‘the cool, calculating deliberation of intelligent people who openly avow that there is an “unwritten law” that justifies them in putting human beings to death without complaint under oath, without trial by jury, without opportunity to make defense, and without right of appeal.’ [26]

Lynching, in other words, was a constituent part of a rationalised capitalist order. Refusing to frame lynch mobs as irrational hordes wielding mass power as a result of a lack of legal infrastructure, Wells rooted lynch mobs’ power in their connectedness to a white supremacist political infrastructure that sought to maintain white social rights by any means necessary. [27]

A 21st-Century Anti-Lynching Movement Must Be Anti-Capitalist

A critical memory of lynching is a political resource for a 21st-century movement against police and vigilante violence, because it allows us to see the reliance of the capitalist state on extra-legal forms of violence – supposedly ‘exceptional’ forms of violence that have nevertheless served as the structural and psychic foundation for white citizenship in the US.

We can learn from Wells’s revolutionary consciousness of the contradictions of a country whose citizens consistently appeal to the law yet allow for lawlessness when illegal force facilitates a racialised class hierarchy. The popular etymology of the word lynching tells us that it is a form of establishment violence that has been committed not outside but to the side of the law. Lynching in the US has been modelled on a Jacksonian ethic of popular sovereignty that holds that the will of the people may legitimately supersede the letter of the law. Historically, it has simultaneously called upon populism and the formal legal system in order to bring together working-class whites and the capitalist class in right (white) exercises of force. Black activists like Frederick Douglass and T. Thomas Fortune began using the word ‘lynching’ in the 1880s to strategically communicate to people that anti-black massacres in the South had the tacit approval of people across the nation and were, in fact, a supplement to formal law rather than its opposite. [28]

In ‘A Red Record’ (1894) as well as in ‘Mob Rule in New Orleans’ (1900), ‘The East St. Louis Massacre’ (1917), and ‘The Arkansas Race Riot’ (1919), Wells underscored the collaborative ethic that existed between police and white lynch mobs, an analysis that activists as ideologically divergent as the NAACP and the Communist Party would repeat throughout the twentieth century. [29]

In her report on the East St. Louis massacre of 1917, Wells highlighted the role that police and soldiers played in the destruction of black life during the three-day riot, which had been orchestrated by white union labourers and carried out with the support of the police and local militia. Wells collected testimony from survivors to prove that the Illinois militia had been both negligent and complicit in the riot. Police, businessmen, and political leaders failed to name perpetrators whom they knew were involved in the rioting, and police either failed to record the names of the white men they arrested or destroyed their arrest records after they’d been released. [30] As in the 1890s, Wells focused especially on the effects of this mob-cop violence on black working-class women and their children.

In her report on the East St. Louis massacre of 1917, Wells highlighted the role that police and soldiers played in the destruction of black life during the three-day riot, which had been orchestrated by white union labourers and carried out with the support of the police and local militia. Wells collected testimony from survivors to prove that the Illinois militia had been both negligent and complicit in the riot. Police, businessmen, and political leaders failed to name perpetrators whom they knew were involved in the rioting, and police either failed to record the names of the white men they arrested or destroyed their arrest records after they’d been released. [30] As in the 1890s, Wells focused especially on the effects of this mob-cop violence on black working-class women and their children.

Though Wells initially encouraged that ‘the strong arm of the law’ be ‘brought to bear upon lynchers’, she was never satisfied with courting the legal status quo. She bitingly chided black elites who ‘counseled obedience to the law which did not protect them’. [31] Arguing that the law was on the side of lynchers, Wells insisted that resisting lynch law required that blacks seek autonomous modes of support outside the law if they were to survive ‘the mockery of justice which disarmed men and locked them in jails where they could be easily and safely reached by the mob.’

Wells not only intervened in white supremacist common sense; she also worked to cripple white supremacist business-as-usual through direct action campaigns. In the aftermath of the Memphis lynching of Moss, McDowell, and Stewart, Wells advised black residents of Memphis to leave the city. She encouraged those who remained to boycott the Memphis streetcar. Much to the chagrin of the streetcar’s owner, many of Wells’s readers took up her recommendation and inaugurated a riders’ strike. [32] And in Southern Horrors Wells called upon blacks to arm themselves and to engage in labour strikes.

Knowing that the American legal system could not deliver justice to black people, Wells also importantly globalised the US anti-lynching movement. In 1893, Catherine Impey and Isabelle Mayo – human rights campaigners who were both active in the fight against the caste system in British India – invited and financially supported Wells to travel around the UK to speak to an international audience about the legacy of slavery in the US and the dire need for anti-racists in the US and Britain to revivify the transatlantic abolitionist network that had existed in the mid-nineteenth century. Wells and her British allies also began an international boycott of southern cotton in an attempt to force southern capitalists to divest from racialised forms of labour control such as sharecropping, debt peonage, the private convict lease system, and public chain gangs. In her autobiography, Wells wrote that after the boycott campaign, ‘the lynching record of 1893 began steadily to decline and has never since been so high.’ [33] Her internationalism influenced later anti-lynching campaigns, such as the campaign waged by International Labor Defense on behalf of the Scottsboro 9 throughout the 1930s.

A 21st-Century Anti-Lynching Movement Must Be Abolitionist

If we are to mobilise a 21st-century anti-lynching movement, we must engage not only Wells’s attention to the intersections of racial and sexual violence, but also her critiques of capital and the state, her internationalism, the shift in focus in her later writings to the militant spirit guiding the survival efforts of black industrial workers and sharecroppers, her advocacy of armed self-defence, and her abolitionist analysis of the policing apparatus that captures blacks in a racialised penal relation. [34]

These aspects of Wells’s praxis grew out of a black abolitionist tradition of testifying to the fully national vagaries of white sexual domination, political control, and the violence of the law. The women who demanded freedom before Congress in the aftermath of their sexual brutalisation at the hands of KKKops during the Memphis Riots of 1866 drew on this abolitionist tradition, as did the black feminist literary tradition that emerged after Harriet Jacobs’s Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, to demand that violence directed at individual women be placed in a larger public context and thus in relation to the collective violence aimed at their communities. Other post-Reconstruction writers like Pauline Hopkins, Angelina Weld Grimke, Francis Ellen Watkins Harper, Mary Church Terrell, Anna Julia Cooper, Fannie Barrier Williams, and Lizelia Augusta Jenkins Moorer similarly emphasised the continuities between sexual attacks on black women and the lynchings of black men through the abolitionist strategies of urgent political speechmaking, coalition-building, and internationalism. [35]

Those of us fighting to realise a world in which all black lives matter must take seriously this abolitionist framework and place it in historical relationship to our contemporary abolitionist movement to end the Prison Industrial Complex (PIC). [36] Prison abolitionists maintain that the US system of mass incarceration – which includes surveillance and policing and cannot be located solely inside prisons and jails – is a geographic solution to the social, economic, and political relations it has been designed to contain. These relations include unemployment, homelessness, drug addiction, and mental illness, and they stem in large part from the unfinished project of the nineteenth-century movement to abolish racial slavery. They are the vestiges of the political compromises that shaped the language of the 13th Amendment and that allowed for the recuperation of white supremacist power after the great promise of Reconstruction.

The PIC is the primary weapon that has been wielded against black life since conservatives sought to retrench the gains made by civil rights and black power movements in the 1960s. Following the wave of riots that erupted in urban centers in the late 1960s to challenge private property relations that promote the under-employment and super-exploitation of black labour, as well as police brutality and other state-backed injustices, conservatives responded by mobilising a moral panic about crime levels that they erroneously alleged were on the rise. Richard Nixon’s 1968 presidential campaign was grounded in the rhetoric of ‘Law and Order’ that marshaled US lynching culture’s historical suturing of criminalisation to black bodies. By individualising revolt in the image of the black criminal, this conservative backlash sought to weaken black revolutionary consciousness and the successful interracial alliances that black radicals were forming with Latino activists and members of the white working class. [37] This law and order project instantiated a punishment industry that, throughout the remainder of the twentieth century, would cut into and largely destroy the social programs and political-educational initiatives undertaken by groups like the Black Panther Party. [38]

Image: Highway I-80 shutdown in Oakland.

The current carceral regime largely relegates black life to the status of a surplus population, in excess of a global, late liberal capitalist economy that no longer profits from US-based ‘unskilled’ labour nor from the reproduction of those ‘unskilled’ labourers. 21st-century police power has been charged with containing this surplus population. Under late liberal capitalism, the surplus section of the working class has been abandoned to the social death of the punishment industry – whose profits it fuels in the form of traffic tickets, court fees, and the private and public contracting of prison labour – and to death at the hands of killer cops. [39]

Prison abolitionists like Critical Resistance, Incite! Women of Color Against Violence, and the Audre Lorde Project seek to abolish rather than strengthen this carceral regime through alternative methods of community accountability. They organise around the intersections between personal, institutional, state, and economic violence against people of color, immigrants, and LGBTQ people, and they highlight how the PIC perpetuates violence against survivors of sexual and domestic abuse. They insist on critical analyses of prison reforms – like the recent Proposition 47, the ‘Safe Neighborhoods and Schools Act’, in California – and caution against ‘reformist reforms’ that further entrench the PIC. [40]

Prison abolitionists have much to offer a 21st-century anti-lynching movement that opposes the role the law and other state apparatuses play in perpetuating the anti-black violence that has always been necessary to the accumulation of capital.

A movement that seeks to end law enforcement and paramilitary violence against black people must engage in a rigorous analysis of the central role that extra-legal anti-black violence has played in the constitution of a liberal democratic regime designed to protect the interests of the ruling elite and their monopoly on social wealth. Demanding that people like Darren Wilson be arrested and charged with murder will not fundamentally alter the reliance of the US criminal justice system on forms of force that exceed the written letter of the law. If we are to mobilise a 21st-century anti-lynching movement with bite, we must continue to engage an abolitionist praxis that refuses to tarry with the rules of a civil society whose liberal henchmen tell us that policing can be better if we are policed by people who look like us. We must develop a deeply historical abolitionist analysis of policing as structurally opposed to black life and look beyond the arrest and indictment of killer cops as the sin qua non of our demands for justice.

A 21st-century anti-lynching movement also requires an abolitionist rejection of the idea that black lives will be more secure if we strengthen black capitalist economic potential. Black people in the US have historically alighted on the fundamental fact that neither labour nor capital have been our saving graces, that we shall not acquiesce to a protestant work ethic nor to its proletarian corollary, and that we therefore need to establish another base of affinity and solidarity with each other, one based not on our capacity to labour.

Our base is our outrage, our indignation, at forms of violence that kill us when we’re young and sequester us until we’re old. Our base is our outrage at the sexual abuses allegedly perpetrated this year against eight unnamed black women by Officer Daniel Holtzclaw in Oklahoma City. [41] Our base is our outrage at the cops who killed Mike Brown, Eric Garner, Ezell Ford, and the women whose names are largely unrecognisable to those outside of women of color justice movements and the prison abolition movement: Yvette Smith, Tyisha Miller, Rekia Boyd, Sharmel Edwards, Shantel Davis, Shereese Francis, Miriam Carey, Tarika Wilson, Eleanor Bumpurs, and Aiyana Stanley-Jones. Our base is an indignation that refuses to quell expressions of rage that target relations of private property and the policing apparatus that is designed to keep those relations in check.

Young activists in Ferguson, New York, Oakland, and other cities across the country have been unrelenting in their rage and unwilling to cede to the prophets of respectability and quietude. That they have harnessed their outrage to militant tactics that target the police and the racialised capital the police serve and protect is a necessary and exciting step in a revolutionary direction. And it is a direction that highlights the movement’s lineal, if unconscious, fidelity to previous anti-lynching movements that made much of the righteous rhetoric and affective force of outrage and indignation. ‘Outrage’ was a term that abolitionists used during the 19th century to describe the violence of slavery and the anti-black massacres that immediately followed its partial abolition. Outrages have always incited black outrage. And this black outrage has been most effective when it is tethered to critique and action, as it was when Ida B. Wells insisted that the outrage of lynching was a state-sanctioned weapon of the ruling class, and when she organised internationally to call out and disrupt the apathy of those who benefitted from racialised divisions within the working class, and from the horrific violence that ensured that solidarity between black and white indigents did not gain force.

The genesis of a revolutionary 21st-century anti-lynching movement that is explicitly feminist, abolitionist, and anti-capitalist was tangible in the streets of Ferguson following Wilson’s execution of Brown, when community members refused to pacify their anger in the face of a militarised assault.

It was tangible, too, at Ferguson October, a mass mobilisation of organisers, educators, media-makers, and students who traveled to St. Louis in early October to situate Brown’s death in relation to the countless acts of lethal violence that are directed at people of color by law enforcement officials every day in the US. At a Ferguson October teach-in facilitated by the Organization of Black Struggle (OBS) dedicated to envisioning black liberation, participants pressed for greater solidarity with political prisoners incarcerated during the freedom struggles of the 1960s, as well as with members of migrant communities being jailed in private detention centers and deported at alarming rates into warzones of US manufacture. ‘We must free them all if we are to have a credible movement’, one activist announced. Others present insisted that a black liberation movement have a strong global analysis of the relationship between anti-black violence and violence against stateless peoples. ‘We need to be internationalists’, another participant commented, ‘but we have to have a program for self-determination that helps us to build power against the capitalist forces and the state’ through the cultivation of economic self-sufficiency, boycotts, and labour strikes.

Since the Ferguson rebellion, and especially since two grand juries refused to indict Darren Wilson and Daniel Pantaleo for the lynchings of Brown and Garner, the direct actions organised by the outraged in defence of black life have become increasingly anti-capitalist – they have included the destruction of property, freeway occupations, gas station and police department blockades, and shutdowns to major corporations like Walmart. [42] These actions highlight our historical debt to past anti-lynching struggles, just as the visual anti-lynching action at UC Berkeley did in December. [43]

The Nelsons’ century-long sojourn from Okemah to Berkeley prompts us to recognise the entwined histories of state policing and extra-legal anti-black violence, and to deepen our understanding of the historically specific ways in which late liberal capitalism profits from the continued incapacitation and liquidation of black life.

Harnessing a critical memory of lynching for a feminist anti-racist movement today means acknowledging that a diversity of tactics as well as an anti-capitalist analysis is necessary if we are to meaningfully confront and cripple the toxic complex of white supremacy, law enforcement, and gender violence in the US. Our outrage is as necessary as our love, and it prompts us to reject the ruling-class history of civil rights which teaches us that our freedom dreams have been staunched by our colorblind present. This is an anti-lynching movement whose full power has yet to be realised.

Erin Gray is a PhD Candidate in History of Consciousness at the University of California, Santa Cruz. Her writing appears in GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art, Open Letter: A Canadian Journal of Writing and Theory, The International Feminist Journal of Politics, and Upping the Anti: A Journal of Theory and Action.

Footnotes

[1] Ida B. Wells, ‘Lynch Law in America’, Arena, 1900.

[2] The phrase was used in the call for a National Day of Resistance, http://fergusonaction.com/day-of-resistance/

[3] Cut-outs of George Meadows (d. Jefferson County, Alabama, 1889), Michael Donald (d. Mobile, Alabama, 1981), Charlie Hale (d. Lawrenceville, Georgia, 1911), Garfield Burley (d. Newbern, Tennessee, 1902), and Curtis Brown (d. Newbern, Tennessee, 1902) were also said to have been displayed elsewhere in Berkeley as well as in Oakland. To my knowledge, no sightings of them were reported.

[4] A few days after the appearance of the cut-outs, an anonymous collective of queer artists of color issued a statement taking responsibility for the images and explaining that their action was meant as an act of historical confrontation that connects ‘past events to present ones’. The collective underscored that the images reference ‘endemic faultlines of hatred and persecution that are and should be deeply unsettling to the American consciousness’ and that the question of taste raised by some of their critics was a straw man, a distraction from their attempt to make visible the faces and names of those thousands of people murdered. See Frances Dinkelspiel, ‘Anonymous artist collective claims responsibility for lynching effigies erected at UC Berkeley’, Berkeleyside, 14 December 2014.

[5] Dani McClain, ‘The Murder of Black Youth is a Reproductive Justice Issue’, The Nation, 13 August 2014.

[6] Paula J. Giddings, ‘It’s Time for a 21st-Century Anti-Lynching Movement’, The Nation, 15 September 2014.

[7] See the African American Policy Forum’s Did You Know? 17 February 2014;

Monique W. Morris, ‘Race, Gender, and the School-to-Prison Pipeline: Expanding Our Discussion to Include Black Girls’, The African American Policy Forum, 1 October 2012;

Insight, Center for Community Economic Development, Lifting as We Climb: Women of Color, Wealth, and America’s Future, Spring 2010;

and the forthcoming ‘Black Girls Matter: Pushed Out, Overpoliced, and Underprotected’.

[8] Angela Davis, ‘Reflections on the Black Woman’s Role in the Community of Slaves’, In Woman: An Issue. The Massachusetts Review, Vol. 13, No. 1/2, Winter - Spring, 1972.

[9] Danielle L. McGuire, At the Dark End of the Street: Black Women, Rape, and Resistance – a New History of the Civil Rights Movement from Rosa Parks to the Rise of Black Power, Vintage, 2010.

[10] Patrisse Cullors, Alicia Garza, and Opal Tometi created the Black Lives Matter movement in 2012 precisely to signal that all black lives matter – to affirm ‘the lives of Black queer and trans folks, disabled folks, black-undocumented folks, folks with records, women and all Black lives along the gender spectrum’. Their call to action has become ubiquitous over the last few months as thousands of people have taken to the streets to demand black liberation. Many of them belong to affinity groups and organisations that are explicitly feminist and under the direction of black women. See Alicia Garza, ‘A Herstory of the #BlackLivesMatter Movement’, The Feminist Wire, 7 October 2014, and the organisation’s website, http://blacklivesmatter.com/about/. As Low End Theory points out, ‘the point here is not, or at least not only, to offer a resounding ‘yes’ to the question of whether or not black lives matter. the point is to render obsolete and impossible the world-making project that makes the value of black life – in and for itself and with others – a question at all.’

[11] It has been really important among queer and abolitionist participants in the Black Lives Matter movement to highlight the specific forms of violence that black trans women experience. Black trans women have the lowest life expectancy in the US, and often meet violent ends at the hands of police, white supremacists, and trans-phobic johns. And because they are trans, they experience especial discrimination in prison, where they are often subjected to the torture of solitary confinement supposedly for their own ‘protection’.

[12] Nell Painter, ‘Social Equality and Rape in the Fin-de-Siecle South’, Southern History Across the Color Line, University of North Carolina Press.

[13] Hannah Rosen, Terror in the Heart of Freedom: Citizenship, Sexual Violence, and the Meaning of Race in the Postemancipation South, Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2009, 9-10; Saidiya V. Hartman, Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America, Oxford University Press, 1997.

[14] Rosen, op. cit., p.6.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Sandra Gunning, Race, Rape, and Lynching: The Red Record of American Literature, 1890-1912, Oxford University Press, 1996.

[17] Rosen, op. cit. See also Gerda Lerner, ‘The Rape of Black Women as a Weapon of Terror,’ in Black Women in White America: A Documentary History.

[18] Rosen, op. cit., p.8.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Lerner, op.cit, p.186.

[21] Bryan Wagner, Disturbing the Peace: Black Culture and Police Power After Slavery, Harvard University Press, 2009.

[22] Alex Lichtenstein, Twice the Work of Free Labour: The Political Economy of Convict Labour in the New South, Verso, 1996.

[23] John L Spivak, ‘On the Chain Gang,’ International Pamphlets no. 32, p.2.

[24] Abdul R. JanMohammed, The Death-Bound Subject: Richard Wright’s Archaeology of Death, Duke University Press, 2005.

[25] Ida B. Wells, Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases, The Floating Press, 2013 [1892], p.23.

[26] Wells, ‘Lynch Law’, p.15.

[27] Rebecca N. Hill, Men, Mobs, and Law: Anti-Lynching and Labour Defense in US Radical History, Duke University Press, 2008.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Anne Rice, ‘Gender, Race, and Public Space : Photography and Memory in the Massacre of East Saint Louis and the Crisis Magazine’. In Gender and Lynching: The Politics of Memory, ed. Evelyn M. Simien, Palgrave Macmillan, 2011.

[31] Wells, Southern Horrors.

[32] Ida B. Wells, Crusade for Justice: The Autobiography of Ida B. Wells, ed. Alfreda M. Duster, The University of Chicago Press, 1970, p.55. See also Wells, Southern Horrors.

[33] Wells quoted in Amii Larkin Barnard, ‘The Application of Critical Race Feminism to the Anti-Lynching Movement: Black Women's Fight against Race and Gender Ideology, 1892-1920’, UCLA Women’s Law Journal 3(0), 1993, pp.19-20.

[34] Matthew Quest, Introduction to Lynch Law in Georgia & Other Writings, On Our Own Authority! Publishing, 2013.

[35] Barbara McCatskills, ‘The Antislavery Roots of African American Women’s Antilynching Literature, 1895-1920’, Gender and Lynching: The Politics of Memory, ed. Evelyn M. Simien, Palgrave MacMillan, 2011.

[36] Rachel Herzing, ‘What is the Prison Industrial Complex?’ Defending Justice: An Activist Resource Kit.

[37] Ruth Wilson Gilmore, ‘Globalization and US Prison Growth: From military Keynesianism to post-Keynesian militarism’, Race & Class 40, 2/3, 1998/99.

[38] Angela Y. Davis, ‘Race and Criminalization: Black Americans and the Punishment Industry’, In ed. Wahneema Lubiano, The House that Race Built, Random House, 1997.

[39] Max Ehrenfreund, ‘How segregation led to speed traps, traffic tickets and distrust outside St. Louis’, The Washington Post, 26 November 2014; Joseph Shapiro, ‘In Ferguson, Court Fines and Fees Fuel Anger’, NPR, 25 August 2014. For literature on the reliance of capitalist accumulation on the existence of an unemployed population, see Karl Marx, ‘The General Law of Capitalist Accumulation’, Capital Volume 1; and Michael Denning, ‘Wageless Life’, New Left Review, 66, 2010. For an account of the racialisation of the US surplus population, see R.L., ‘Inextinguishable Fire: Ferguson and Beyond’, Mute, 17 November 2014. On the role of the racialisation of the informal economy and its impact on Eric Garner, see Salar Mohandesi ‘Who Killed Eric Garner?’ Jacobin, 17 December 2014.

[40] Alexandra Natapoff, ‘Opinion: Prop 47 empties prisons but opens a can of worms’, SFGate, 6 December 2014.

[41] Holtzclaw has been charged with forcible oral sodomy, first-degree rape, sexual battery, indecent exposure, first-degree burglary, and stalking.

[42] Tyler Zee, ‘Burn Down the Prison: Race, Property, and the Ferguson Rebellion’, Unity and Struggle , 11 December 2014.

[43] Because the response to the imagery at Cal, especially on social media, was overwhelmingly conservative – commentators swiftly deemed the lynching images to be hateful ‘effigies’ that destroy black dignity, trigger ‘bad’ feelings, halt political mobilising, and incapacitate the movement – it is crucial to recall the black radical tradition of appropriating lynching imagery in the service of protest. The cut-outs, as Leigh Raiford argued in her defence of the action, are elegies rather than effigies; they inform the long history of speaking back to white supremacist terror by appropriating its tools to remember the dead and to call the living to action. Raiford reminds us that describing these cut-outs as ‘effigies’ – as did UC Berkeley Chancellor Nicholas Dirks in his message to the Berkeley community the day following the images’ appearance – imagines the people pictured in them as ‘figures to be despised and destroyed’. Effigies, Raiford reminds us, are fashioned in order to be undone and to mirror the undoing of those they represent. Leigh Raiford, ‘On Effigies and Elegies’, Insurgency: The Black Matter(s) Issue, 23 December 2014. See also: Berkeleyside Editors, ‘Community responds to noose effigies found at Cal’, Berkeleyside, 13 December 2014.

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com