Riot Polit-Econ

In this riposte to the moral backlash against the UK’s August riots, The Khalid Qureshi Foundation & Chelsea Ives Youth Centre survey the ‘immiseration industries’ ushering in the emerging regime of work/fare and worklessness

On 17 August, Mayoral buffoon and sometime nth grade littérateur, Boris Johnson, announced his official response to the riots. Despite his allergy to accounts of ‘social and economic justification’, Johnson took the occasion to propose a supplementary £20 million fillip for his £50 million London Wide Regeneration programme. Not only this, Johnson continued, but the Mayoral Office would be disbursing a still more philanthropic £3.5 million ‘High Street Fund’, the resources for which had been scraped from the open palms of such incorrigible givers as Barclays, BP, Capita, Deloitte, RBS and Lloyds. For every smashed window on an outer city high street in Haringey or Charlton, a Mother Theresa from the auditing-accountancy oligopoly; for every small proprietor grieving over his emptied shelves, a battery of policy documents bearing solemn promises of maximum regeneration impact. Thus the wounds of our broken society are cauterised. But for those whose abundant faith in universal human benevolence and Deloitte is tempered by intelligent pragmatism, questions impudently arose. Who would administer these funds? Who would be granted the honour of bean counting his way back to social stability? No answers were immediately forthcoming. As the days ticked by, and as the reports on judicial repression poured in, and as retailers of plate glass watched as their sales figures boomed, still the questions went unanswered. Six weeks passed. Prisons bulged. At last, on 4 October, the Mayor’s Office announced that the Greater London Council’s two ‘high-powered taskforces’ would be led by Sir Stuart Lipton (target: Tottenham) and the merely plebeian Julian Metcalfe (target: Croydon). They are a symbolically significant pair, this corporate Tweedledum and Tweedledee, for Lipton is the real estate developer responsible for the City’s grim financial services ziggurat, the Broadgate Centre, while Metcalfe founded Pret A Manger, under the proliferating striplighting of which migrants from the EU are today forced to beam inanely, for a subsistence wage, in satisfaction of the all-too-effective demand from high-wage FIRE sector workers for luxury afternoon comestibles. Here they are, Lipton and Metcalfe, one responsible for the palace of the financial services sector, the other for its ‘ethical’ servants’ barracks, the torn halves of a whole which in fact does add up, like the pieces of a simpleton’s jigsaw, to provide an image, in charming miniature, of our domestic model of economic ‘growth’.

The first draft of the following text was written before this was yet known. It was, or was meant to be, an early and desperate attempt to leap off the carousel of cretinous recrimination on which fascistic journalists, ‘left wing’ politicos and automated politicians all rode, weeping and gurning and clinging to their war ponies. As such, its sections constitute a preliminary investigation not into deprivation or senselessness, nor yet into ‘austerity’, but into the new profitable industries in immiseration that have for the last few years flourished in what establishment discourse insists is a void; one which is impossible to remedy unless Sir Stuart Lipton and Julian Metcalfe expand into it. It doesn’t take an unreconstructed clairvoyant to guess that Johnson’s extra £24 million will be dynamically pissed away on the miserable step-changes of a regeneration policy from which no one save Pret A Manger’s new owners – Goldman Sachs – are apt to benefit: and still there is work to be done.

Image: Rachel Baker, Alienation Affect, 2011

Organised Criminality I (aka Unemployment)

For a while now we’ve been inundated with phenomenologies of the new regimes of workfare, developed by new graduates whose abandonment to the desiccated labour market at least affords the opportunity to put their Husserl to good use. But, some questions: what about the macroeconomics of unemployment in the UK? How can we understand the misery of work in terms of the misery of worklessness, when these two conditions are becoming ever more intimately related in the lives of most proletarians forced to live in the dungeon of domestic capital accumulation? We ask not only about the degradation of conditions of employment down the supply chain, in the informal sectors of the international labour market (even fascistic fashion journalists allow their moral fibre to bristle at the thought of those kinds of globalised immiseration), but about the conditions of life for those who ‘succeed’ in climbing out of unemployment and into work.

The question first of all demands the iteration of some basic banalities. Like all good communists, we repudiate without hesitation the reactionary separation of consumerism and production, the privileging of the former over the latter, and the attendant pantomime dreamwork of consumer metaphysics, which tendentiously positions all humanity in an income continuum which denies all qualitative distinctions, including especially (and intentionally) the distinctions of class, whose truth outvies the corruptions of mere accountancy. Now more than ever the interface of ‘work’ and ‘consumerism’ in our society is rotten: it is the loop by which long term structural unemployment recreates the market for low end consumer commodities and by that means also recreates the jobs which the long-term unemployed are expected to aspire to.

In Peckham, the windows of Burger King are smashed in. In the cavernous Lidl next door to it, the five members of staff who at any one time provide the entire workforce are pulling down the shutters. The manager is probably grateful for the break, because now he can get the cashier to do some sweeping. In Lidl labour is many-sided: exhaustion and humiliation have a great number of facets. The worthlessness of the majority of the jobs available in an economy whose service sector has expanded is the qualitative critique of unemployment statistics.1 Companies like Lidl, Aldi, Primark and Fortune 21, celebrated in the Companies sections of the Quality Financial Press for their swift footwork in the face of market headwinds – i.e., for profiting from new poverty – have expanded rapidly over the last two years. Lidl and Aldi increased their market share by 10 percent in the three months running up to January 2011.2

All this would be old news if only it didn’t dovetail so nicely with State employment policy. Capital management ideology states that because the administration of the unemployed requires the expenditure of taxation monies, long-term structural unemployment is a decelerator on private sector dynamism and nothing else. Naturally this is just a straightforward lie. The ‘no frills’ service industries are an important destination for the monies disbursed to benefit recipients. As the State continues to huff credit back into the financial sector, crossing its fingers and hoping that its preferred bubbles might reflate, it also endorses as never before long-term structural unemployment; and it therefore ensures continued and growing demand for the cut price commodities that the ‘no frills’ service sector provide and which the immiserated must consume. As anyone can see, this means a net transfer of jobs from the ‘frills’ service sector (i.e., old misery) into Lidl, Aldi, Fortune 21, Primark, and so on; and because the frills that these companies remove are, in the first instance, wages for their staff, the managed production of unemployment is equivalent to the managed degradation of the worst ‘legitimate’ forms of capitalist work. In this pirouette, bad work, which, as anyone who has ever replenished a shelf in a Tesco can attest, is not exactly pastoral (it is preternaturally shit), reaches a new nadir. Working class unemployment and working class work are remodelled together in a grisly bump‘n’grind, and both are made ever more foreign to the forms of bourgeois work and bourgeois unemployment which the doctrinaire professors of bourgeoisdom – using their own class categories as a circular warrant – insist they must resemble.

While it is often pointed out that the sharp distinction between the public and private sector is specious – which is to say, an intellectual fabrication belonging to capitalists, whose next move is always to turn the distinction 90 degrees, so that it forms a hierarchy of value, i.e., private sector dynamism vs. public sector bureaucracy – the argument we make is slightly different. Because ‘long-term structural unemployment’ alters the structure of demand for basic commodities, which then need to be sold at a profit, it creates new impetus for the carnival of wage reduction – the race to the bottom as spectacle in the epoch of Silvio Berlusconi, eBooks and famine. In other words, ‘long-term structural unemployment’ is the etiolated hieroglyph of a new circuit of accumulation premised on the intensified exploitation of the employed. This is true even before we start to monitor State efforts to push private-sector wages below the legal minimum which it imposes, as its civil service functionaries scramble to put to work their hypertrophied flexible skill sets in the innovation of new forms of ‘workfare’ torture.3 As the civil servants might put it, the stagnation circuit is a ‘formal’ economy with all of the best features of the ‘informal’ economy (e.g., no guaranteed pay).

The State happily attaches to this profitable stagnation circuit a label marked ‘aspiration’, as if it were an expressionist ballet, which from the moderate heights of Downing Street it does perhaps resemble; and the press gesticulate at their demonstration-model abyss and moan about the ‘nihilism’ of the riots which shattered the facades of so many betting shops; and the sky does not fall in. But fulmination against the destructive ‘nihilism’ of the riots merely underwrites what it claims to protest against, because it refuses to acknowledge just how much of our social ‘fabric’ would have to be destroyed if any social life were to be more than accidentally liveable. In the future, it must by now be obvious to anyone without a derivatives portfolio that effective social action will have to be more and not less destructive, because less and less of it is capable of being transformed merely by a modification in the terms of ownership. However important concerns about the ‘proper’ targeting of destruction may be, when their social function is to serve as a gag – and it usually is – better not to let them be put in your mouth.

Human Superiority to Wonga

In 2010, the online lender Wonga.com came eighth in the website Startups’ list of the top 100 new companies. Providing reasons for Wonga’s placement, the website states that

[CEO] Errol says [the company is] all about bringing a convenient and speedy solution to short-term cash needs, and lending as responsibly as possible. Wonga has already processed well over half a million loan applications and secured a $22m venture capital funding round in the summer of 2009.

This already says quite a lot. According to the Bank of England, in the last 25 years secured debt quadrupled as proportion of earnings; by contrast, unsecured debt rose only slightly.4 This is all very useful for anyone who wants to reflect on property boosterism during the last round of British capitalist growth – even the economists who overpopulate the Bank of England’s financial policy teams dimly intuit the truth of it – but the data also conceals some important areas for materialist inquiry. For example, it doesn’t begin to tell us under what terms that unsecured debt was loaned out; nor does it tell us by whom – though the fact that economists at the Bank of England are uninterested in this is more understandable, since analysis of exploitation isn’t one of the Bank’s ‘core purposes’, any more than Ben Bernanke is the universal subject-object of history, or any more than critical analysis of the organic composition of capital is one of the ‘core purposes’ of his maids. But, then, under what terms was the debt lent out; and by whom?

Between 2006-2011, as the retail arms of the banking sector put its orgies of ebriety behind it and got sensible, the ‘payday loan’ industry quadrupled.5 What this means is that an increasing proportion of debt advanced to the working classes has been lent on increasingly severe terms. As debt support organisations wish so passionately to inform us, the growth in the payday loans industry means cycles of debt misery for the expanding industry’s ‘repeat customers’. Concerned parliamentarians have of course gladly seized the opportunity to emote some vote winning concern. In 2010, a noble band of 31 MPs clubbed together to sign a motion against payday loans lending. In the acrid mixture of intolerable circumlocutory jargon and decorous moralism so typical of parliamentary rhetoric, the motion stated that

the House [...] believes that lending of this kind can prove both socially and financially irresponsible and that the Government and appropriate regulatory authorities should insist on the application of the regulatory principle of fair treatment of consumers which currently applies to savings and investments in the UK to sub-prime lending products to protect vulnerable consumers. 6

Shuffling aside the motion’s gamut of illiteracies, we should note that it was essentially a call for transparency. Extortion is bad when it ‘irresponsibly’ uses ‘television advertising’ to delude oafish consumers – some of whom are vaguely ‘vulnerable’ – into acquiring debt which they won’t be able to amortise. The focus on deception makes real social tendencies irrelevant since, according to the debauched enlightenment thinking of provincial MPs, social suffering is fine so long as it isn’t advanced by mis-selling. ‘Social causation’ – that catch word of liberal determinism – is therefore transferred away from material reality and into the phantasmagoric graphic design hothouses of the maleficent advertising sector; and the nauseating vocabulary of consumer taxonomy (the ‘vulnerable consumer’, the ‘satisfied consumer’, the ‘consumer in need’, the ‘thrifty consumer’, the ‘irresponsible consumer’, etc.) falsifies the two most significant consequences of the transfer of unsecured debt from the retail banking sector to the payday loans industry. Firstly it ignores the fact that more and more proletarian cash is canalised into debt servicing, the nearest equivalent to coal shovelling that the field of consumption has to offer. Secondly, it occludes the involvement of conventional banking capital in the loanshark sector’s growth.

Who is protected in this conversion of ‘irresponsible’ lending into a moral problem? When politicians and liberal ‘campaigners’ pump their little fists and ‘insist’ on ‘responsibility’, what they do, whether they know it or not, is draw a cordon sanitaire around bad capital in the interests of good.

As Startups’ lyric poem to Wonga suggests, in this sense squarely in the anti-physiocratic tradition of political economy, capital doesn’t just grow out of the ground. Marxists should be more than interested in just taking the pulse of this growth industry: they should be climbing directly into its ventricles. The Chief Executive of Dollar Financial, Jeffrey Weiss, whose company (serving ‘unbanked’ and ‘under-banked’ consumers) is currently expanding into the UK, estimates that ‘we’re maybe 25 percent of the way towards a full country build-out... you extrapolate from our current 350 stores I think there is a potential universe for us of 1,200 locations.’ And corporate tumescence on a scale this cosmic requires large sums of venture capital, at least some of which originates with banks, the newly discovered responsibility of whose retail divisions is what allowed the payday loans industry to jack up its growth forecast in the first place.7 For example, Dollar Financial in 2009 emitted $600 million in unsecured notes (i.e., interest bearing debt) due for repayment by December 2016. Much of this debt is required to finance its aggressive expansion strategy (aka Jeffrey Weiss’s macho ‘build-out’ on his 100 percent proletarian treadmill), but the extortion industries it is accumulating worldwide, including the Swedish exploiters Sefina and Folkia AS and the British pawnbroking business Sutten & Robertson, themselves rely on the official banking sector for their lines of capital credit. Dollar Financial’s ‘lines of capital credit’ are the tentacles of ‘legitimate’ capital investment, seeking new returns.8 Capital in the ‘irresponsible’ payday loans industry is bank capital or, indeed, is just capital as such, doing what it does best in a period when extortion replaces asset inflation as the menacing guarantor of net valorisation.9

After smashing their way into the local money lending store, rioters on Peckham High Street had a shot at opening the safe. Since they weren’t professional safebreakers, they finally contented themselves with smashing the counter and looting the chairs. When the police vans arrived, the chairs were hurled through their windscreens. If only Liberal Democrat politicians were less artificially horrified by the display of pure criminality – or whatever else is today’s anti-analytic collocation of choice – they might commend its innovative lateral thinking and present the participants with Young Enterprise Awards, small cash prizes and an opportunity to visit the town hall to receive a framed A4 certificate from the mayor.

Organised Criminality II (aka Class Formation)

On Peckham High Street, on 8 August, as the riot moved up the road towards Camberwell, kids were pulling motorcyclists from their bikes. When one rider stood up and staggered in a daze back towards his vehicle, five or six men knocked him back over and kicked him. As his ribs were broken, the atmosphere in the street was festive. Anyone who didn’t object was in: solidarity was extended to anyone who would by virtue of their presence underwrite the necessity of the action.

After the riots concluded with the obligatory surge of policing operations, and as a thousand bobbies flocked onto every street and into every KFC, these were not the experiences of community most discussed by the British bourgeoisie. When rasped by its lips, the term referred to any group of inscrutable ‘others’ who defended their shop windows or inventory, and who therefore – though they may not have meant to, or have said as much (but the British bourgeoisie can forgive their inarticulacy, because it takes such pleasure in speaking on their behalf) – defended the sanctity of private property as such. In the welter of blatant class strategising that ensued from 10 August, this use of ‘community’ was hatefully unavoidable.Across the land, talk show sofas buckled under the weight of garrulous ‘community leaders’, eager to retail the usage back to the bourgeois journalists who were principally responsible for its origination.

But because the definition of community as a property owning community is so truncated, banishing, as if by ASBO, a good number of forms of human sociality which might appear in fact to be highly communal, it requires some explanation; and class spokespeople wasted no time in stretching the meaning of another concept to fit its interests. Thus we were treated to a thousand slurred treatises on the concept of the ‘gang’. The gang, we discovered, is distinguished from the ‘community’ on the grounds that a community defends private property whereas a ‘gang’ undermines it, or, if it doesn’t undermine it, steals and eats it, or uses it to play Xbox.

This is of course, terrific bullshit. Upstanding ‘communities’ do not get to have the private property which they so valiantly defend except by benefiting from exploitation (whether directly or indirectly), or by dabbling in illegal forms of accumulation the profitability of which is to some degree tailored to level of risk. Bourgeois moralising of ‘communities’ vis-à-vis ‘gangs’ is therefore a means of deleting from its vocabulary of social explanation the capital relation or, in other words (and more simply), is a means of ignoring what people have to do in order to acquire the property which they later attempt to preserve, and this is hardly surprising, since no one has got more from doing severely unpleasant things (to other people) than the bourgeoisie. And while there might certainly be ‘exceptions’ to the rule that property is usually acquired, in the first place, through exploitation or through crime (and who doesn’t love an exception?), ‘communities’ which establish their small property holdings in the only other fashion possible, i.e., by submitting to the most hateful and never ending drudgery, are a source of moral inspiration only to those who enjoy the benefits of their servility.

Thus as the white movers and shakers of Dalston fall in love with the baseball bats which (they convince themselves) were wielded by Kurdish shop owners not, surely, on their own behalf but disinterestedly, or (the delusion is just as grandly disingenuous and really amounts to the same thing) on the behalf of the community, it isn’t hard to point to contravening evidence. The website ‘Gangs in London’ claims that:

[t]he families that make up the Turkish and Kurdish criminal organisations of London have imported 1,000’s of kilo’s of heroin into the United Kingdom during the last three decades. During which time they have made links with British criminals, including the so-called ‘Liverpool Mafia’, the ‘Irish Godfather’, Christy Kinahan, Albanian people trafficking networks, east London Asian crime families, Chinese Snakehead gangs and the predominantly black street gangs within the boroughs of Hackney and Haringey.10

To which list we could speculatively append Santander, Wachovia and a lustrous host of other cartels, owned predominantly by whites. There are no pure communities; there are only groups of people struggling to live under capital; and all the bourgeois weasel words of moral purity are at bottom a play for class hegemony, dangerous both because they lend themselves to racism and because they can be put to work in stymieing any discussion which doesn’t restrict itself to juggling a few moral platitudes siphoned from a discarded copy of The Evening Standard.

The quotation above therefore (and others like it) is useful as a preliminary inoculation against the worst stupidities of bourgeois response; but it evidently doesn’t tell us much about the recycling of ‘illegitimate’ profits into ‘legitimate’ petit bourgeois enterprises – of the kind which splay along the high streets at the city’s fringes, and which are now (or even now perhaps already were) the toast of those who would usually prefer to shop in outlets owned and managed by people of their own class and ethnicity. Nor does it tell us about the role of gang profits in accentuating ethnically profiled class differences within geographically defined ‘communities’.

From our current outpost on the cloud of unknowing it would be irresponsible to speculate about different gang forms and, in consequence, it’s difficult to speculate on the variant means by which gangs are plugged into different circuits of legitimate (low level) accumulation.11 One valuable line of inquiry might investigate the historical relationship of gangs – and therefore of criminal profits – to the citizens’ credit union, whose tightening of the sweet bonds of the community is extolled so lovingly by politicians eager to ensure that citizen-promoted debt servitude can replace traditional (redistributive) forms of state provision.12 Red Tories, Blue Labour and the attendant gaggle of Christian citizen groups together, become the communitarian cheerleaders for forms of extortion and immiseration newly moralised because they are conducted on a ‘horizontal’ and not a ‘vertical’ axis.

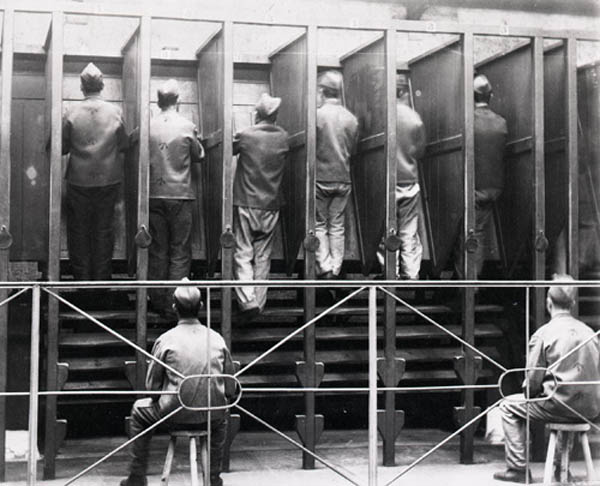

image: Prisoners on the treadwheel at Pentonville Prison, 1895.

Conclusion on a High

And when discussion comes to the issue of drugs – as discussion inevitably does, whenever it isn’t on pause while the liberal discussants feign to weep about absentee fathers or rap music – the ‘legitimacy’ Hydra raises once again its terrible network of heads. Amid all the talk about the lamentable involvement of ‘our youth’ in the drug trade, with its descants on ‘slow motion moral collapse’ and its shrill undertone of bourgeois asepsis (i.e., just don’t let them infect us), not much has been said about the involvement of the banking sector in ‘handling’ (i.e., laundering) the ‘proceeds’ of that trade.13 It might just be conceivable that one or two of the people who last week lobbed bricks through the windows of their local Santander have, in the past, made some cash from street dealing, but it can be guaranteed that they didn’t make as much as Santander itself, squarely implicated along with Bank of America, HSBC and others in large scale laundering.1414

If laundered drugs money is a literally indispensable source of liquidity for a banking system gone costive on its own toxic debts and wallowing in ‘public’ opprobrium, it is obvious why these unacknowledged legislators of the world have no interest in even the managed decriminalisation of drugs. The task for us then is not to accuse the state of ‘hypocrisy’ – a term which belongs to art and bourgeois ideologues who, because they are removed from positions of political power, have no interest in disguising their prejudices – but to identify the contours of the complicity of state capital in nurturing organised crime; and to specify the dependency of legitimate (i.e., legally recognised) capitalist institutions on the profits generated in a purportedly ‘extra-legal’ economy.

In the last fortnight, no one could have failed to be subjected to riot analysis, unless they’ve had their head buried in the little pile of sand they keep specially prepared in their panic room. Such analysis is worked out usually by means of tidy acts of discrimination, accomplished at various degrees of sophistication or crudity, by salaried entities more or less human. By now we know the cast of the drama they construct: looters and till workers, citizens and politicians, organised gangs and anomic school kids, shopkeepers and crime lords, the deprived and the comfortable, those whose acts can be understood if not condoned and those whose privilege earns them only contempt. The distinctions have this character, that they eventually subordinate themselves to a more abstract distinction between victims and perpetrators. With the astigmatism of class hatred now so well implanted and the judicial system running on autopilot, Justitia has no need to put her blindfold back on.

But it is necessary for capital and its representatives to avail themselves of all their resources of discrimination. The resources are a desperate bulwark against the apperception of what binds us together, which is the social necessity for capital to accumulate under conditions of straitened reproduction.

Time will continue to go by, and, most likely, it will continue to be said that gangs are the consequence of inner city deprivation. That statement has an implicit tendency. If only more capital would flow into the estates in which their members live, gangs would melt into air. Just as in Tottenham the looters seemed, according to the standard colonialist clichés, to ‘melt’ into the side streets. Once again, we can feel safe in ‘our’ cities. This is the official, rubber-stamped mythos of capital accumulation. The gangs exist because their members are separate from capital. Where there is no capital, there is deprivation. This is deprivation’s definition. The mythos serves two functions. First, by premising deprivation and its dark bedfellow, ‘crime’, on separation from capital, it apes the angel of history and announces capital’s absolution, because capital cannot be responsible for that from which it is separated and which it no doubt yearns in its heart to reach. Like Jesus, capital loves all human resources. At most (according to this argument), the fault lies with doltish town planners, callous politicians and other marionettes in the shop window of social obfuscation. Second, the mythos provides an abstract and tendentious ‘vision’ of what at any given point accumulation is, in the sense that it suggests that capital investment can be expanded at will to eradicate the stain that, e.g., the Pembury Estate has left on our community, but also, by parity of reasoning, in the sense that it implies the real circuits of accumulation do not currently depend for their completion on exactly the forms of human torture brought about by reified ‘underinvestment’, but instead just happen to operate elsewhere, in other places, far away from the sad and frightening little people who spoliate their local Betfred. This report has attempted urgently to specify the contours of a few of the new and profitable immiseration industries. It has done so not just because they exist to be pointed out, but because we hate the fatuous moral philosophies which take a professional interest in ignoring them. As the commentators continue to waddle onto the tattered red carpet under the ‘public eye’ to play with their Fisher Price scale of good and evil, performing narcissistically their games in moral philosophy, and refining their breviary of ‘sociological’ distinctions, who can say how many extra burnt out cars and shops and flats it will take, and how much more concentrated misery and desperation and venom, to demonstrate in spite of all this that in at least one respect we truly and undeniably are all in this together: under capital, right up to our necks.

Footnotes

1 For a very useful worker's inquiry conducted by an employee of Lidl, see, Frank L. Ludwig’s ‘The Lidl Shop of Horrors: Working Conditions in Lidl’, http://franklludwig.com/lidl.html. See also, ‘Arbeitsbedingungen bei Lidl’, Der Spiegel, 10 December 2004, http://www.spiegel.de/wirtschaft/0,1518,332171,00....

2 Both of these companies have flourished by the enthusiasm with which they strangle their workers. For example, Lidl’s wage policy has always been based on the imposition of impossible workloads which must be completed by workers during (unpaid) overtime, which is to say, on the unpoliced and unremunerated extortion of extra-contractual labour.

3 Corporatewatch recently posted an interview with a 24-year-old Bangladeshi woman made to work three days a week in Primark as a condition for the receipt of her Jobseeker’s Allowance. Assuming a work week of 21 hours and a subsistence ‘benefit’ of £50.95, this woman was paid an hourly wage of £2.43, (http://www.corporatewatch.org/?lid=4030). This is obviously a rather venerable means of manipulating the market rate for ‘unskilled’ labour, but as state politicians natter on about ‘skill creation’ through workfare, which is to say, as they continue to promote virtualised accumulation for the exploited, the real exigency for wage regulation reveals itself: competition is hotting up in the no frills sector. Last month US Primark clone Forever 21 opened its first retail branch on Oxford Street, http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/a72a0814-b863-11e0-b62b-... This might, as the Financial Times boorishly reports, be good news for ‘teen consumers’, but price competition in low margin retail industries requires the licensing of new peaks in worker exploitation. Otherwise the margins go sour.

4 Matthew Hancock and Rob Wood, ‘Household Secured Debt’, Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin, Autumn 2004, http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/quarte...

5 For anyone who wants ‘proof’ that bank lending to individuals fell off from late 2008, the Bank of England provides a graph, http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/statistics/li/2011/...

6 Early day motion 1194, http://www.parliament.uk/edm/2009-10/1194

7 See Rupert Neate, ‘Loans start-up Wonga gets $22 boost from Facebook backer’, The Telegraph, 8 June 2009, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/newsbysector/ba... Balderton Capital, the main supporter of Wonga, claims neatly enough that most of its US$1.9bn capital comes from University endowments. Academics at Harvard would do well to reflect on this as they release themselves upon the tiny cucumber sandwiches served at the latest social justice colloquium.

8 http://www.reuters.com/finance/stocks/DLLR.O/key-d... and http://www.reuters.com/finance/stocks/DLLR.O/key-d...

9 For some (now somewhat outdated) information on the debt collection growth sector, see: http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp- dyn/content/article/2005/07/27/AR2005072702473.html The best survey on recent private sector dynamism in the UK incarceration industries is Clinical Wasteman, ‘Unlimited Liability or Nothing to Lose’, reprinted in this issue of Mute, pp.22-27

10 See London Street Gang media resource’s ‘London’s Mafia? History of Turkish & Kurdish Organised Crime in London’, http://gangsinlondon.blogspot.com/2011/03/londons-...

11 Even the bourgeois social-justice-police-surveillance enterprise, The Centre for Social Justice, acknowledges in its 2011 ‘Dying to Belong’ report that little has been done in the way of usable (i.e., repression facilitating) history from above. Thus the report hilariously frets that ‘[t]he MPS found 171 gangs operating in London and the Home Office estimate that there are 356 gang members in the Capital. This would mean around two people per gang, which would not, by the Home Office’s own definition, constitute a gang.’ (p.20) And since there are presumably at least some gangs with three members or upwards, it would seem to follow that according to the Home Office’s own estimates there exist many gangs with one member or fewer, http://www.centreforsocialjustice.org.uk/client/do... As the notorious gang Walt Whitman once put it: ‘I contain multitudes’.

12 An extreme instance of the kind of informal credit network operated via gang formations is reported by David Cohen in ‘Heroin wars, loan sharks and executions: the Turkish gangs terrorising north London’, The Evening Standard, 17 November 2009, http://www.thisislondon.co.uk/standard/article-237.... Naturally any instance less extreme would bear less interest for journalists writing for this paper.

13 See Michael Smith, ‘Banks financing Mexico gangs admitted in Wells Fargo deal’, Bloomberg.com, 29 June 2010; http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2010-06-29/banks-fin...

14 In an excellent recent essay in black-market/legit-market partnership, John Barker notes that ‘[f]igures extrapolated by [Tom] Feiling suggest that just one percent of the retail price of cocaine in the USA goes to the Colombian coca farmer; four percent to its processors and 20 percent to its smugglers. Seventy-five percent therefore is realised in the rich world.’ How much of that is realised as profits by the rich world’s banks remains to be assessed. See ‘From Coca to Capital: Free Trade Cocaine’ in Mute Vol3 #2 Spring/Summer 2011, http://www.metamute.org/en/articles/from_coca_to_c...

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com