Ferguson, Missouri. Most of us never would have heard of it, but many have now had the conversation: Where the hell is Ferguson? St. Louis, sort of?

But not simply St. Louis. Ferguson is not just a neighborhood in a sprawling city, as Watts is to Los Angeles or Flatbush to New York. This is attested to by the involvement of the Ferguson Police Department and County police forces in suppressing the recent riots, rather than the St. Louis PD, at least prior to being taken over by state on August 14th. The militarized police on the streets of the small city have not been drawn from the familiar standing armies, such as the NYPD or LAPD, but are instead a conglomeration of armed groups organized at the county level to manage those zones that lie beyond the reach of the traditional urban police departments. Aside from its own police, Ferguson has its own fire departments and its own school district. This is because it is not an urban neighborhood, but instead a fairly traditional post-war American suburb, independently incorporated as its own city.

This might seem to be a mundane fact, but it actually hints at much more significant shifts in the economic and racial geography of US metropolitan zones over the past twenty years. Without understanding these shifts, we cannot hope to understand the riots themselves, much less how they might overcome their limits in order to become a more sustained and disciplined assault on the present order.

Probably the most widely repeated thing in the mainstream accounts of Ferguson is that it has only become a conventionally poor, majority black neighborhood in the last decade. Like many postwar suburbs, the city’s heyday was in the 1950s and 1960s, which saw successive doubling of the population until it reached a peak of nearly 30,000 in 1970. Deindustrialization beginning in the ‘70s was then matched with a continual drop in population, to about 21,000 today, in line with St. Louis’ historic population loss.[i] But this was not so much a simple decline in total residents as it was a process of white flight, in which many wealthier people left the region as the economy was restructured, their aging houses taken over by poorer people seeking better schools and housing, neither of which existed in the deindustrialized and then mildly gentrifying core of urban St. Louis.

In some cities, this restructuring left hyper-diverse poor neighborhoods and suburban immigrant enclaves in the place of formerly white suburbia. Seattle’s southern suburbs, to take one example, are now as much as 30% foreign-born, with school districts stressed under the pressure of student bodies with upwards of thirty different native languages, from Amharic to Mixtec to Cambodian. Meanwhile, a number of suburbs in the US South and Southwest now have more residents speaking Spanish as a primary language than English.

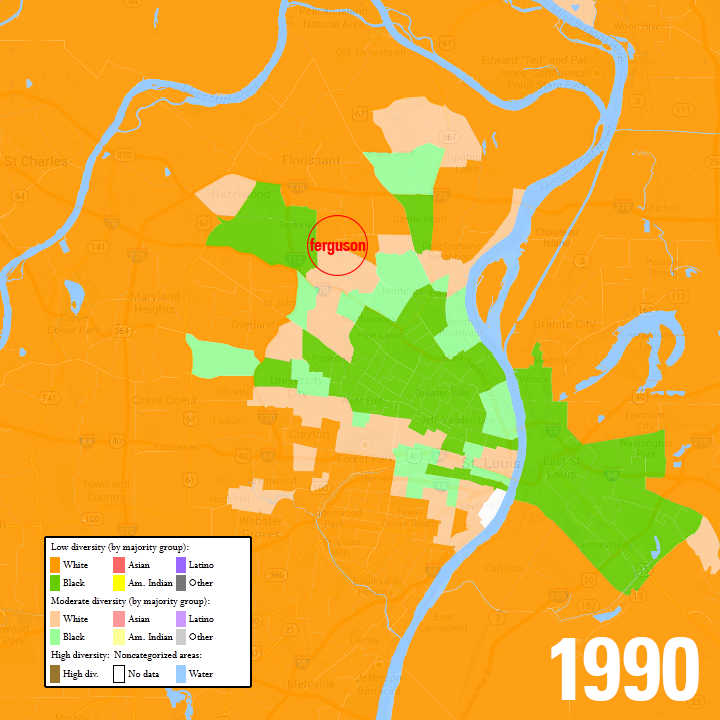

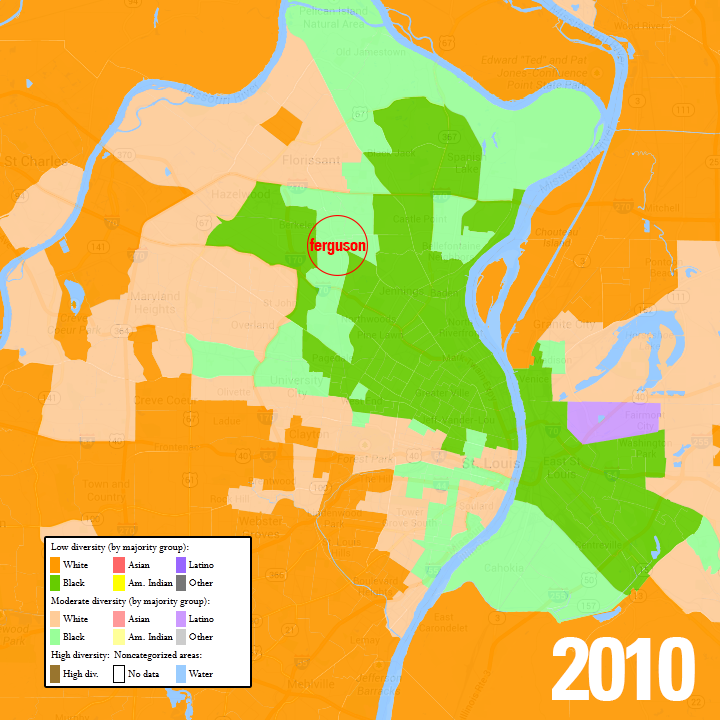

But in many cities within the older rust belt, the process was less one of new migration and more a restructuring of existing patterns of segregation. This often saw the hollowing of the old city, the solidifying of some traditional inner-city ghettoes in Detroit-style environments of urban decay, and, in a few cities, the expansion of new zones of poverty outward into the suburbs. In these cities, the new segregation did not take the form of light diversity / high diversity, as in West Coast cities such as Seattle, Sacramento, and San Francisco, but instead retained its character as a white / black divide. St. Louis was one of these cities, but whereas others like Philadelphia, Detroit and Baltimore simply saw the consolidation of the traditional inner-city ghetto in the past twenty years, St. Louis saw both a condensing of its urban poverty and a suburbanization of this poverty.

Much of this demographic change has come in the last twenty years. As late as the 1990 census, the city was still 73.8% white and 25.1% black, but by 2010 this situation had entirely reversed, with 29.3% white and 67.4% black. Poverty had grown more severe and median income had either stagnated or dropped in the region, when adjusted for inflation. In Ferguson, unemployment doubled from around 5% in 2000 to an average of 13% between 2010 and 2012.

The St. Louis metro area in 1990, with census blocks mapped by majority race. Data from www.mixedmetro.us

The St. Louis metro area in 2010, with census blocks mapped by majority race. Data from www.mixedmetro.us

This follows national patterns in the suburbanization of poverty, with more poor people in the US now residing in suburbs than in large cities.[ii] These national trends also signal a significant shift in the racial geography of the country, as thoroughly gentrified urban centers like New York, Seattle and San Francisco may soon be encircled by banlieue-style rings of suburban poverty and public housing, with the poor increasingly banished from the interior of the city and new migrants settled outside municipal borders. Other cities have seen a resurgence of interior decay and the compounding of urban segregation. The St. Louis area has seen both.

The American Riot Evolves

The 1960s and 1970s saw riots cascade across the US, from coal fields to college campuses. But the riot’s most familiar terrain was, by far, the inner city ghetto. Forced by exclusionary housing covenants to reside within a select few neighborhoods, the poorest residents of most major cities were confined to urban cores and excluded from the newly-constructed postwar suburbs. This condensed the country’s racial geography, even while it divided the geography of class according to color.

The events that we think of as archetypical American riots (the Watts riot, the King assassination riots, etc.) are actually specific to the particular racial geography of their era. And this racial geography is, in many major metropolitan areas, simply no longer the same. After the 1970s, the ghetto was destroyed, occupied or further walled off, and a significant segment of its population was literally exported to prison camps. The Pruitt-Igoe housing project in St. Louis, the city’s only substantial public housing, was demolished in 1972. The demolition was hailed as a leap forward in efforts at urban renewal, and by the Reagan administration public housing was being demolished at record rates, replaced with Section 8 vouchers, the vouchers themselves scaled back under Clinton and then restricted further by austerity policies after the economic crisis.

The effect was that “the projects” were literally gone. Reform of the housing market and the growth of a bubble in sub-prime mortgages also meant that many of the country’s poor were not only allowed but now encouraged to leave the inner city, which was under pressure for redevelopment. Gentrification paved over the old slums in New York, San Francisco and Seattle. In cities like St. Louis, urban cores simply decayed while gentrification happened in a few select regions, school districts collapsed and population hemorrhaged. The site of Pruitt-Igoe remains a gaping ruin in the heart of the city.

And riots began to change shape accordingly. The 1992 Los Angeles Riots were the first in a new type—mischaracterized by the media as “race riots,” the events in LA were more that of a general, decentralized uprising which made no demands and, in so doing, were able to cohere a new national atmosphere around them, as riots again spread across the country. No longer were the riots simply limited to a district or two, as had been the case in the Watts riots thirty years prior. Now rioting spread with the entire city as its substrate—a tendency seen again, though in more limited ways, in Cincinnati in 2001.

It is not coincidental that this new national sequence of rioting began in LA, one of the US’ most suburban cities. The Los Angeles riots were a window into the future, their decentralized geography foreshadowing the evolution of the American riot as it adapted to the new ghettos that, in 1992, had only begun to be built. And now, twenty years later, Ferguson offers us a second window: this time into how those new ghettos might burn.

The Suburban Riot

As partisans of the riot, then, what lessons might we extract from recent events? Many seem to assume that past patterns will simply repeat themselves. Black youth will formally unite in some new sequence of organizations, simply picking up the torch dropped forty years ago by the Black Panthers. But the concrete features of everyday life that gave this process of organization its grounding has been demolished. The dense, tightknit communities are in most places gone. Where they remain, they are fundamentally fractured by constant surveillance, police occupation and the imprisonment of young men. Maybe more importantly, there are no longer national revolutions and decolonization processes worldwide to provide an ideological grounding for ethnically-exclusive forms of organization, while in the majority of US cities poor neighborhoods are more and more multiracial. This makes both “revolutionary nationalism” and pan-Africanism less and less attractive as organizing principles for young people today, even while a reactionary nationalism might always lurk on the horizon. A symbol of this irrelevance, the so-called “New Black Panther Party” was seen in Ferguson pushing protestors back from police lines and directing traffic.

Despite apparent continuity, then, a sharp divide exists between historic US racial uprisings and what is presently underway in Ferguson. This divide has now taken on concrete form, as young rioters have begun explicitly rejecting leadership from older, state-sanctioned leaders in the “black community.” As a recent New York Times piece makes clear:

One protester, DeVone Cruesoe, of the St. Louis area, said this week as he stood on Canfield Drive, “Do we have a leader? No.” Pointing to the spot where Mr. Brown was killed, he said, “You want to know who our leader is? Mike Brown.”

But if the most coherent method of overcoming the limits of the ghetto riots came in the form of the Black Panther Party, and if this is impossible to simply parallel today, then what might future acts of organization look like? In order to begin exploring this question—and it certainly will not be answered here, nor in any text, but only on suburban streets lit by burning gas stations and strip malls—we must look at the tactical context that has allowed the events in Ferguson to take on their particular character.

Police killings have sparked outrage and limited riots in many cities in the US in recent memory. But none of these events have been able to take on this same character, and none have been this difficult to suppress. An urban counterpart to events in Ferguson was the 2013 Flatbush riots in New York. These riots, similarly sparked by a police murder, were crushed much faster than the riots in Ferguson, despite the fact that they seem to have attracted larger protests and garnered greater immediate and active support from the surrounding neighborhood. So what accounts for the difference? Why did Flatbush not create the type of national atmosphere that Ferguson has?

The difference between the two is primarily one of terrain. Flatbush is in a central inner-city zone, monitored and occupied by the world’s seventh largest standing army, the NYPD. The uprising took place in a city that, after the ghetto riots of the late ‘60s, was completely redesigned for riot suppression—avenues were widened, housing projects were dispersed, movable objects were chained to the sidewalk, etc. When the riot broke out, it was deftly suppressed by well-trained tactical squads operating on an urban battlefield that had literally been built for them.

The first two nights of soft suppression were capped by a third night where riot police moved in and made mass arrests, picking up the majority of the most active young people (43 in total) and threatening many with felony-level crimes—both damaging the immediate riot and hindering the possibility of future events by beheading a germinal leadership. This was followed, as always, by the “good cop” stage, where progressive politicians like Jumaane Williams and NGOs like “Fathers Alive in the Hood (FAITH)” called for an end to the riots and a return to the status quo, embellished with a few hints at official inquiry into the murder and promises of legislative reform—all of this framed, of course, as the will of the “black community.”

In Ferguson, by contrast, the rioting erupted in a region with so many micro-municipalities that some local police departments have as few as five officers. The county and city government, pumped full of military-grade equipment but lacking in people trained to use it, found itself wielding a police force that was both inept and heavy-handed. These suburban police were well-armed but also ill-trained in riot suppression. They fired teargas almost immediately—something that the NYPD hardly ever does, and other large police departments only use when they must clear a space rapidly or force an evacuation of territory that has been occupied for some time (like Oscar Grant Plaza). They then shot a second person. And, for all that, they failed to make significant mass arrests, were unable to corral protestors, and mostly just stood parked in front of big box stores firing tear gas canisters. They were so inept, in fact, that the state stepped in, putting the highway patrol in charge.

One reason that the tactics failed, however, is that the suburbs themselves are not designed for the prevention and crushing of riots, as are the major cities. Corralling protestors becomes nearly impossible. The police have few staging areas that are secure, nearby and out of sight. The rioters’ targets are more dispersed and cannot easily be defended—large forces have to be committed to basically sit in front of strip malls and other big targets, spreading the police thin across the terrain.

The rioters, meanwhile, can mesh into the residential surroundings much easier, and new centers of rioting are formed in areas by as few as four or five people setting something on fire or breaking some windows, after which others gather. The rioters are highly mobile and not dependent on public transportation, which can easily be surveilled, constricted and redirected in urban areas, hamstringing the ability of the riot to spread. Census data notes that 79.8% of the workers in the city commute to work in a personal vehicle alone, while another 9.4% carpool. These vehicles not only provide easy, fast transportation, but serve to amplify the energy at different nodes of the riot. Photos and videos from Ferguson show protestors surrounding their cars, blasting Lil Boosie’s “Fuck the Police,” at the police, for example.

Finally, in Ferguson there are no “good cops.” Not only are the city’s police almost entirely white, but so are its politicians, with a white mayor, white police chief, five white city council people and one Hispanic one governing a city that is now two-thirds black. There are simply no “community leader” figures equivalent to Jumaane Williams capable of softly suppressing the anger and selling out the more radical youth. Faced with this dilemma, the government literally had to ship in a black liberal leadership from St. Louis proper, adding Al Sharpton for good measure. Police were then ordered to march with the protest staged by these “community leaders,” and the governor handed over command of the department to a black Highway Patrol Captain named Ronald Johnson, who was promptly pictured hugging marchers in staged photo-ops.

All of these features are going to be repeated issues for the state in its attempt to prevent and crush suburban riots in the next decade. Small, micro-municipalities have not adapted to the influx of poor residents that they have seen in the last twenty years. These cities are ill-designed for riot-suppression, the police are over-armed and under-trained, and no soft counterinsurgency in the form of black churches, “community leaders” and NGOs has been established.

This is very much the situation predicted by the Italian insurrectionary anarchist Alfredo Bonanno over twenty years ago:

The presence of these ever widening ghettos and the message that is crying out from them is the main flaw in the new capitalist perspective. There are no mediators. There is no space for the reformist politicians of the past.

In Flatbush the mass arrests, followed by the progressive politicians and church groups, completely suppressed and destroyed the momentum of the uprising. In Ferguson, the night after Al Sharpton showed up and a black man was put in charge of the police, youth came out and rioted again. They fought the cops, lit fires and expropriated goods. Now the staged hugs are over and the peace vigils are pockmarked with the sound of rain and shattered glass. The governor has been forced to declare a state of emergency, and may soon send in new police squadrons from all over the state.

After the news conference where the governor announced the curfew, angry residents were clear that this was only the beginning:

I don’t think this is gonna be nice at all. Violence will be met with violence.

It appears that, tonight, the new ghetto burns like the old one.

Phil A. Neel

[i] All data is from the 2010 Census and most recent American Community Survey, which, for most variables, is the 2012 ACS.

[ii] For the most extensive study on this phenomenon to date, see Berube, Alan and Elizabeth Kneebone, Confronting Suburban Poverty in America. Brookings Institution Press. 2013.