The Liars Wouldn’t Let it Lie

Robert Dellar's recent book on the Mad Pride movement and belligerent patienthood buries the pseudo-opposition between effective 'activism' and fulfilment of unwholesome social needs. Clinical Wasteman welcomes one more excuse to kick the twin corpses of Mental and Musical Hygiene in his review of Splitting in Two: Mad Pride and Punk Rock Oblivion

Our safest bet is to call him mad...he has simultaneously been bribed into the acceptance of our ways and punished for his inability to do so.

- Philip O'Connor

An open-plan zoo would end badly for the rich.

- Socialism and/or Barbarism

It's a strength, in revolution, to despise the enemy.

- Jules Michelet

Robert Dellar despises the enemy so generously that a lifetime of exposure to counter-revolutionary triumph is not enough to stop him. Generous as in prolific and as in magnanimous: pity the empowered idiots who would destroy you in order to Help you. Petty pushers of the Chemical Cosh are – or are going to be – sorry in all senses.[i] ‘Despite’, the noun drawn from the verb ‘to despise’, is the opposite of envy. One consequence of which is that actual hatred can be saved up and turned against the whole thing: the therapeutic arm to start with, but sooner or later the total social body that it dangles from.

Up to and during my early days at the Hackney Hospital, I would tend to blame the psychiatric profession for the abuses it inflicts upon those it purports to help. Over time I modified this belief and saw the wider picture, realising that the essential problem is capitalism.[ii]

That 'wider picture' might leave room for a lot of left-commentarist armchairs, but Robert Dellar didn't sit in them. His writing makes it quite clear that the essential problem was never a puzzle to be solved by the 'high-functioning'. He comes to call the problem 'capitalism' while spending the equivalent of certain lifetimes fighting and, incredible as it sounds, occasionally winning against the technicians of punishment: the obvious suspects with the slick cellside manner, the enhanced legal powers, the Largactyl and the keys to throw away. The ones with the monstrous presumption to want what's best for you.[iii] If Dellar and some of the other Proud Mad saw greater monstrosity in the social set-up moving the monsters, their 'abstract' insight depends on direct exposure, unwholesome engagement with the near-term enemy.

The unwholesome is important here. On one level it refers to the sordid air breathed by anyone who gets close enough to professional punishers to have to try to outwit them. But it also applies in the sense of the back cover warning from Out to Lunch that Dellar's 'reminiscences impart a strange, unwholesome joy, like smoking a cig dipped in popper juice'. The Proud Mad were not about to engage the enemy in a game of competitive cleanliness. Dellar calls back from the dead or from damaged life a succession of heroes, but there are no role models among them, not even a presentable victim. When he writes that his 'favourite riots were the spontaneous ones, expressions of joy as much as dissatisfaction' he means riots in the regular street-mayhem sense, but also the older and broader sense of 'riot', encompassing all kinds of lawless, licentious and insubordinate joy, which pervades the story of Mad Pride and its antecedents from the start. And as the book also suggests, the two senses of the word are not so neatly partitioned.

If you think that sounds an easy – or worse, a book-reviewerly – thing to celebrate in someone else's description of the past, please try to remember the following two points.

- Every 'sympathetic character' in the story is beset at one time or another or at all times by acute distress. Suffering runs riot in the rioters, and most of the time they're punished for their trouble: locked and/or beaten up and/or knocked out by multi-medication, the crippling results of which are duly noted as symptoms requiring further confinement and more medication. Not surprisingly, many simply didn't survive.

- These same prolific sufferers, the designated punch-bags of therapy, accomplished feats of desperate strategy and practical solidarity that sometimes put the healthy Left to shame.

So the unwholesome element matters because the accomplishments of mad power are unlike (which is not to say 'greater than') any others and should not be mistaken for points scored by healthy, dutiful activism. No doubt the short, scandalous effectiveness of (eg.) Pete Shaughnessy's Reclaim Bedlam, the partially reclaimed Tower Hamlets, Hackney and Southwark Mind branches, the North East London Advocacy Network, Hackney Patients' Council, Hackney Anarchy Week and Mad Pride can't be attributed wholly to the riotous reflexes engaged – the book shows how much repetitive, nerve-rending work the rioters had to do – but it surely didn't happen in spite of the unseemliness either.[iv]

An advocate...was a comrade helping you to communicate with professionals, as well as fulfilling administrative tasks which you might have trouble doing yourself... It's a task best undertaken by those who have been through the system as users themselves, people with their own problems... Real advocates should refuse to eat in staff canteens, be cognisant with street slang and dress with their arse hanging out of their trousers (p.46.).

In other words a clean advocate is no advocate at all. 'Advocate' was one of the jobs Dellar held in and against the mental illness system. Filling in disability benefit forms for comrades who couldn't was not strictly part of the job, but in effect it was advocacy itself. (Competent form-filling is expert performance of incompetence, a nasty double-bind if your survival depends on it. A clumsy claim goes straight to the Recycle Bin, but an articulate applicant must be too healthy for 'help', too indifferently abled to be allowed the means to live.) Dellar dislikes the word 'patients' inasmuch as it 'somehow suggests inferiority', but he prefers it to 'client' or 'user' because at least it doesn't 'try to disguise the power imbalance between themselves [i.e. "patients"] and practitioners designated to help them' (p.39.). The difference between a potential patient who can fill in the form and one who can't is circumstantial, quantitative. Whereas the gulf between both and the agent who deigns to decide on the claim is – at least at that moment – qualitative, a difference in material and categorical kind. Or in other words again, pre-professionalisation advocates and the mad they advocated were all 'patients' of the institutions that treated, employed or otherwise presumed to 'help' them. And sometimes those patients shared techniques that could turn their illness – their presumed subordination – into a weapon.[v]

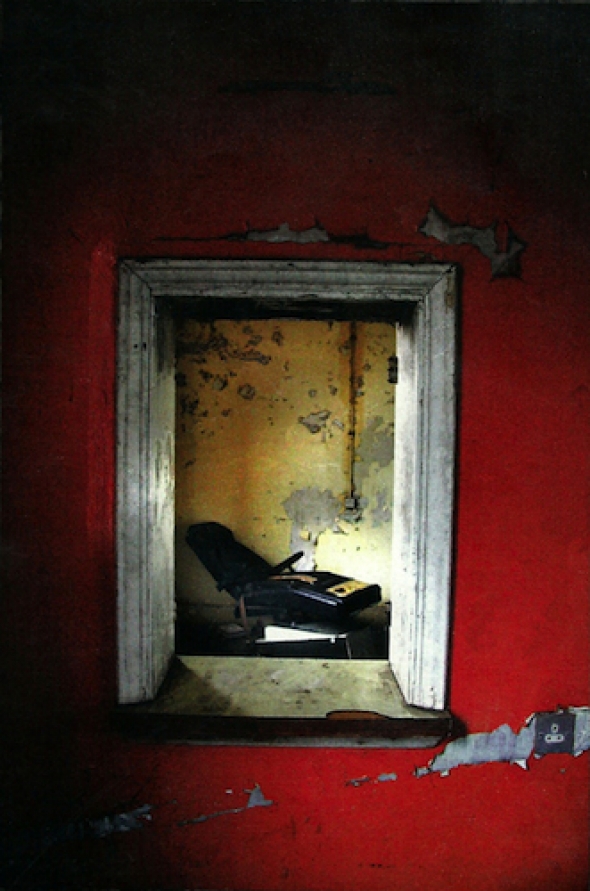

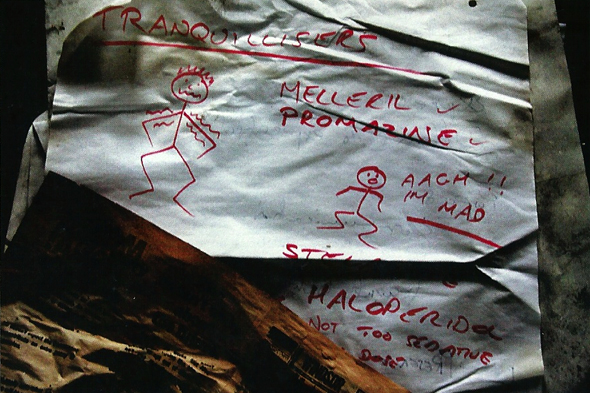

All photographs by Max Reeves (S-Kollective), taken in the remains of Helllingly Hospital. First published in Max Reeves, Lois Olmstead, Howard Slater, 'From Hellingly', Papakura Post Office n.1, Entropy Press, London, 2010. http://s-kollective.com/downloads/2012/ppo-01-from-hellingly.pdf

The techniques may be no big deal if you're in a position to recall them as modestly as Dellar does, but they're a revelation if, say, you loitered on the outermost Mad Pride margins back then – knowing that something must have underpinned such dirty fireworks – and now can finally learn more than was let slip by that best of all millennial xerox zines, the Southwark Mind newsletter. And if you read about these rational mad acts today and still think there was anything easy or small-time about them, please check your sense of perspective into the nearest wrecker's yard.

Or to put it yet another way, it's one thing for Robert Dellar, who actually did the job, to say that the 'befriending' of patients more distressed than he was 'wasn't exactly hard' (p.39.). But any reader who agrees that it must have been easy is unworthy of a moment's ease in his or her whole life. The uneasy part is not just the mutual personal exposure of one fraught subject to another, but the mixture of that invitation to injury with an institutional structure built to multiply insult. The friendship between a professional helper and the recipient of 'help' is that of a keeper with a zoo animal, and the kept know it. Even a non-professional who gently nudges or offers good advice is an evangelist. The right word for a friend who tells you something 'for your own good' is an enemy. So when Dellar really did befriend supposed 'clients' in spite of the 'befriending' mechanism, collaborating in their self-defence against doctors, welfare arbiters, etc., the last thing that social relationship could have been is 'easy'.

Still on page 39, Dellar prevents a typical institutional stitch-up – a divide-and-rule attack on low-grade wages at Tower Hamlets Mind – through 'some rabble-rousing' and the 'carving up' of an executive committee meeting. This sort of purposeful hellraising, which recurs throughout the book, is not an easy trick to pull off either. Of course 'results-orientated [sic] behaviour' is grist to the professional appraisal mill: a hell-bent sense of purpose is standard in careerists unwilling even to raise limbo. And every patient (in the broad sense) reserves the right to call all bets off, to repay insult with interest and make trouble on a scale corresponding to the knowledge that there's nothing to get.[vi] But what's unusual (perhaps impossible unless a few King Losers act together) is the combination of the two: the recklessness that keeps keepers frightened, carefully directed towards an end they're pledged to prevent. 'Nothing-matters-any-more' abandon applied with calculation to something that matters.

A full account of that calculated abandon will not follow here, because that's what Dellar's book is for: what he describes is too much – qualitatively and quantitatively – to repeat, and any digested version would cut it back down to something like its regular Size Zero media presence. But it's worth mentioning that the unwholesome school of advocacy was carried all the way to PICU (later the Bevan Ward): 'the dreaded psychiatric intensive care unit, the lock-up ward at the Hackney Hospital where in theory the eighteen most psychotic people in the borough at any one time were incarcerated' (p.45.). When Dellar arrived there as a Hackney Mind advocate, 17 of the 18 PICU patients were young black men whom the doctors and nurses already 'seemed scared of' (p.65.) and managed with pre-emptive violence. 'Bare life' is not colourless: the power of decision over life and living death is class-ridden in general and 'racial' (i.e. constitutive of 'race') in particular. Black PICU captives tended 'to be there only because of racist stereotyping'; like other Invasive Care recipients but more often, they were 'subject to gratuitous and unnecessary forensic assessments to determine the "likelihood" of them becoming criminals, leading some to private hospitals and special hospitals like Broadmoor with little chance of getting out' (p.66). Among things Dellar and his friends/comrades/colleagues definitely did not bring to this brutal, racist and sexist set-up were: romantic esteem for Otherness; Ethical empathy; brittle Revolutionary cheerleading; a Good Example. Some things they did bring (to the Hackney Hospital and elsewhere) were: aggressively partisan paperwork; committee coups; subversive procurement; ex-triumphalist overseers laid low and afraid to retaliate; enough attention to what patients actually said to apply in practice the principle that we are the experts in our own distress. Efficient leaderless mischief and rigorous patient-led research.[vii] And also: actual fireworks; a flaming psychiatrist effigy; other unedifying artworks and enough commandeered space to make them in; a welter of contra-indicated alcohol; a recaptured ECT machine; the run of a doomed hospital building; punk rock.[viii] (Oh, and the 'humiliation' of a hyper-competitive Hackney psych nurses' football team by a bunch of bare-living mad(wo)men, discreetly helped by a few 'top-ringer' friends of Patients Council chair Terry Conway. 'The ringers were straight-faced and conscientious as they described the depressing details of their fictitious hospital admissions, and we stuffed the nurses 12-2...it was the worst thing that had ever happened to them' (p.75).)

No-one ever said they would win outright, though. Death would always be at least as proud as madness; most captives couldn't be sprung by mad advocacy alone and some would never get out at all. And those who did eventually walk would never be exempt from distress, because a distress-free response to the only available freedom, i.e. not-quite-incarceration within a class-structured and as such automatically racist, sexist world, would be the most insane of all 'behaviours'.[ix] The current National Mind catchphrase – 'One person in four will experience mental illness in any given year' – might almost make sense if what it meant was: 'Watch out! A quarter of the people around you may be deranged to the point of contentment!' But unfortunately it turns out to be a lavishly advertised, government-backed promotion of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy for all.

Still, by the time this coalition of literal and figurative firestarters began to burn out, quite a few managers of madness had been taught the proverbial lesson they would never forget. And the onset of exhaustion in the outwardly invisible counter-clinical work overlapped with the riot of sick self-assertion that was very visible as Mad Pride. The works of which stand alone and speak for themselves, and in case they didn't already, are now described in Dellar's book at the level of their panicked, prosaic making. Mad Pride sold out print runs and gig venues effortlessly, or rather in a frenzy of effort but without the 'help' of publishers/labels/promoters and the sort of self-abasement that entails. Dellar says so himself, but it's worth repeating here because it's worth considering why. Dellar is right to insist that the music, art and writing was mostly formidable by any criteria (eg. Ceramic Hobs, ATV, Nikki Sudden, Gini Simpson's films, the Mad Pride anthology/Seaton Point authors...) but when was that ever enough to generate uncompromised sales? One bestselling product was a black t-shirt with Penny Mount's Mad Pride logo – in which a gaping circled 'A-for-Anarchy' engulfs the rest – printed on it in white. Dellar attributes much of the t-shirt's popularity to the appeal of the Anarchy emblem itself: it 'became an indispensable fashion item, even amongst people who weren't aware that it referred to a mental health campaign'. But maybe he's over-modest here on everyone's behalf. How many of those who shelled out £10 for the shirt and actually wore it can really have been clueless about the kind of gig (or whatever) they were buying it from? Or even if they had no idea to start with, were they still oblivious by the time they headed for the merchandise table? For what felt from the middle distance like five or so glorious minutes (but as the book makes clear, was an exhausting eternity for those doing the work), the Mad Pride proposition reached far beyond the inner wrecking crew of service users and immediate allies. The Garage and the Union Chapel were packed; the city seemed stained with the logo; SANE was actually scared (see below). It would be easy enough for someone to make a case that the t-shirt buyers, audiences, readers and hangers-on in general were glamorizing bare survival from a comfortable height. But that case would be malicious, untrue and an invitation to stupid, retroactive despair. Anyway, I don't recall seeing much Charitable condescension at those events. What went on looked more like a lot of drinking, dancing, smoking, listening and arguing in a crowd containing some officially certified waste(wo)men along with other members of the working class and middle-underclass who were wise enough to expect to be next. If you think that doesn't amount to much, remember that what passed for political and media common sense at the time was aggressive promotion of respectable Hardworking-class Values by disrespectful proprietors of hard work and its prizes, owners eager to deflect the hatred they objectively merit onto a mad or simply slovenly 'residuum'.[x]

And remember too that this controlled explosion of mad artistry coincided with some of the best pieces of purposeful hellraising ever visited on the officers and cheerleaders of the British Mental Health Police. The last quarter of the book runs through so many episodes so fast that it's almost hard to keep up, but one that stands out is the campaign against SANE ('Schizophrenia: A National Emergency' [aghast emphasis added]): a charity funded by the likes of Glaxo Smith Kline and King Fahd bin-Abdulaziz al-Saud to push 'the media message that psychiatric patients are dangerous and should be locked up'.[xi] An early indication of the SANE approach to resurrecting Mental Hygiene was 'an onslaught of billboard posters, featuring the image of a woman looking distressed, with the strap-line: ‘You don't have to be mentally ill to suffer from mental illness’. What they meant by this was that it's not only the ‘mentally ill’ who are distressed by their condition, but also the people around them who are forced to put up with their existence.'[p.111] Dellar swiftly dealt with that slur by passing off as authentic SANE propaganda a modified poster featuring the face of Tory health minister Virginia Bottomley and the corrected slogan: ‘You don't have to be mad to be mentally ill, but it helps.’ But unfortunately the liars wouldn't let it lie. Around this time the New Labour government was starting on the first of three attempts (the third was successful) to pass a Mental Health Act bringing in fast-track sectioning, free-improvised drug combinations that would be called 'lethal cocktails' if discovered in the recreational sector, and Community Treatment Orders requiring outpatients to submit to the Chemical Cosh and other intrusions on pain of instant and indefinite inpatienthood. SANE's 'role in whipping up media hatred of mental health service users, with [SANE founder and Daily Mail columnist] Marjorie Wallace repeatedly drawing a link between "mad" and "dangerous"'[p.111], was a godsend to government efforts to pass off the raid on patients as Humanitarian Intervention, fulfilment of a Responsibility To Protect.

A group called Survivors Speak Out tried early on to picket SANE headquarters and was quickly dispersed. Starting not long afterwards, though, a swarm of users, survivors and sundry hellraisers loosely co-ordinated by Southwark Mind besieged the pro-incarceration lobby for months and finally sent SANE cringing back out of the state campaign, to the point that Wallace even pretended not to have supported Community Treatment Orders in the first place. As Dellar tells it, the name 'Mad Pride' was decided on at Pumpkins café in Hackney at some point during the siege. Which is not hard to believe, because the combination of serious organisation and unwholesome artistry that left SANE 'never...quite the same'(p.120) will be familiar to anyone who ever saw Mad Pride in action. The final demonstration, during which Wallace was escorted back to her 'plush office' by police for her own safety, involved fake doctors in white coats, a giant syringe built by sculptor Cat Monstersmith, impaled images, unmarshalled cacophony, the bellowed poetry of Frank Bangay, and a lot of national media suddenly happy to cover patients' loathing of 'a charity that claims it's trying to help them' (p.120). But it might not have sowed such perfect panic had Shaughnessy and Dellar not exercised their legal right to 'inspect' SANE's offices and accounts shortly beforehand, or if the users/survivors/patients hadn't already fed the professionals' paranoia to bursting with a far finer grade of polemic than lobbyist language guidelines allow. SANE eventually found itself appearing to defend Enoch Powell – the father of Care in the Community! – in one press release and inventing friendly survivor movement contacts in another, only to be publicly debunked by the groups named, who 'confirmed that Wallace was lying' (p.114) and promised to stand with the cacophonists on the Ides of Mad March: 15/3/99.[xii] This 'victory in itself' (p.120) didn't ultimately stop the Mental Health Act, but it did deprive the pro-psychopolicing side of one of its slickest PR outfits. How much that contributed to holding up the legislation (which was derided even by psychiatrists themselves) will never be clear, but the Act didn't get through until 2007: depending how you count it, scorn and intimidation (both from the survivors themselves and, on their astral plane, from the doctor lobbies) won patients something like a seven-year respite from the disgusting mechanisms now in place, whereas polite apologetics from anybody would have obtained precisely nothing.

At the same time, the toil and care spent preparing what looked like a wild collective outburst apparently cost Robert Dellar the use of his pancreas (pp.120-1). He was well tended-to by friends, and the fact that the ordeal claims no more than a page and a half of the book suggests that he either recovered quickly or learned to do without that pesky organ altogether. (He signs off 15 years later, surprised to find himself 'a free man'.) But the episode provides as good a pretext as any to note (too late) that Dellar never separates the stories of advocacy, troublemaking and artistry from others about the personal entanglements, attempts to hold onto income and housing, substance preferences/renunciations and clinical patienthood of the narrator and other people close to him. These parts are at least as important as anything else in the book: the only reason less is written about them here is that the reviewer personally detests all reviewers' commentary on the psychosocial lives of writers and their 'characters'. A relatively conscientious critic might confine herself to some harmless adjectives about the presentation of those lives ('unsentimental', 'funny', 'distressing', 'tender' and 'violent' would all apply in this case, for what their application would be worth), but a proper Saturday Supplement hack would happily wade in and start judging the personae. Which of these people is good, bad, charming, demonic? Do they get what they deserve? Questions that bespeak weapons-grade presumption every time they're asked.

But the following can still be said in spite of my probably pathological scruples.

- Dellar makes it impossible for the reader to think of the collective feats separately from the unreviewable personal circumstances. 'Public' and 'private' stories never alternate neatly: the two are so closely entangled that nothing can be considered without considering everything else.

- The 'private' circumstances (eg. prodigious self-medication, acute interpersonal spite between people who adore each other, legally and physically porous housing, endless work and corresponding poverty) might strike some readers as chaotic, but others will recognise them as normal.

- Dellar strictly avoids apologising for anything, least of all from the memoirist's standpoint of 'hard-earned' later wisdom. (His disdain for the blackmail of 'earning' is rigorous throughout.) And with equal strictness he abstains from romantic celebration of personal distress or of anything else that might be construed as 'chaos'. No 'lifestyle' was either the fatal flaw or the secret weapon of Mad Pride, and no reader is allowed to imagine otherwise.

And then finally, this is literature, as the disclaimer at the beginning declares. Which means the whole thing is no less cumulatively true just because its synthesis of plain description, allegory and invention declines to line up for journalistic or scholarly fact-checking. The late Pete Shaughnessy probably didn't throw a sado-psychiatrist from the top of a fast-moving train; perhaps Robert Dellar wasn't really re-imprisoned in an occult PICU and never turned the full weight of the Chemical Cosh on one of its prescribers before quietly walking back out. But the facts as the writing imaginatively renders them require at least that much as an epilogue. Auditions for the new live-action version are open now.[xiii]

Clinical Wasteman (as indicated elsewhere, it's a description not a name) wrote this for CAMERON BAIN, who is unlikely to see it.

Footnotes

[i] Chemical cosh: any combination of psychiatric drugs administered forcibly to save the administrators the trouble of knocking the patient unconscious.

[ii] Robert Dellar, Splitting in Two: Mad Pride and Punk Rock Oblivion, Unkant Publishers, London, 2014, p.59. All unfootnoted page references refer to this book.

[iii] Yes, you may have read that sentence or something like it on this site or nearby before. Repetition, repetition, repetition! Consider it a symptom: perhaps 'we' (never to be specified) will stop going on about monstrous presumption when They (actually existing) stop wanting things for us.

[iv] Note to any Ethical literalists reading: please stop. Or if you must continue, be advised that 'unwholesome', 'unseemly' etc. are used here in a strictly positive sense. 'Work' and 'accomplishment' likewise appear on a short-lived literary ticket-of-leave from their usual horrible connotations.

[v] No attempt to nail either Dellar or Mad Pride to the SPK slogan ‘Aus der Krankheit eine Waffe Machen’ is intended here. Nor – need it really be said? – is the point supposed to be that there's anything automatically or even usually revolutionary about illness, distress and misery. The phrase is borrowed only by way of insisting that, for these patients too, the belligerent impulse (and the corresponding strategy) is not external to the 'madness' but built into it.

[vi] You can't help him, nobody can / and now that he knows / there's nothing to get / will you still place your bet / against the neighborhood threat?

- Iggy Pop, Neighborhood Threat (Lust for Life album, 1977, side two).

[vii] In 1994 volunteer advocate Phil Murphy and 'revolving door' Hackney Hospital patient Earil Hunter contrived a way to 'float around the bin unchallenged' for 'several weeks', systematically interviewing patients on 'treatment, social conditions leading to admission, diet on the wards, safety, any thing and everything else we could think of'. The published results, picked up by local and health-professional media, were 'devastating, possibly putting the final nail into the hospital's coffin' (pp. 62-3). Although when the Tower Hamlets Gazette ran the headline Hospital of Horror Slammed in Report, the 'horrors' quoted came from the 'positive feedback' section of the document.

[viii] If readers of the sort invited to stop in note 3 above are still reading anyway, please be re-advised that what goes for 'unseemly' goes double for 'unedifying'.

[ix] The right word is 'world', NOT 'society'. There's no such thing as the latter. Thatcher and Graeber are both right about that, though one is right about nothing else and the other about not much more.

[x] Yes, just like now, in case any newborns or amnesiacs are reading. On the 19th-century origins of the 'residuum', a category now more often called 'underclass' but largely unchanged in its meaning, see Gareth Stedman-Jones, Outcast London, Oxford U.P., 1971.

[xi] Dellar, p.111; on the funders (also including a Greek shipping dynasty and the Sultan of Brunei), see the SANE website itself: http://www.sane.org.uk/uploads/sane_news_2013.pdf

[xii] Not a bad year, as a lifetime of bad years goes: those Ides came three months and three days before June 18, 1999.

[xiii] Mad Pride (http://madpride.org.uk/index.php) shows no sign of stopping. One excellent recent slogan was: Piss on Pity! The focus on the 1990s-early 2000s in the review is because it's a review of a book about that period.

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com