Minor Politics, Territory and Occupy

In a talk given by Nick Thoburn at the School of Ideas this February, some of the Occupy movement’s most hopeful qualities were magnified through the lens of Deleuze and Guattari’s theory

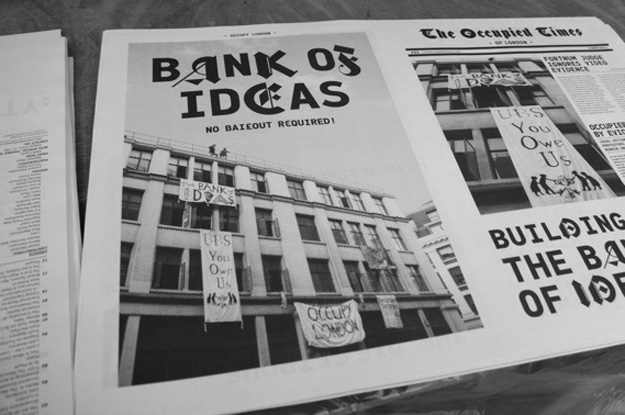

The following is the text of a talk given at Occupy London’s School of Ideas as part of a workshop called ‘Deleuze and Guattari and Occupy’, 25 February 2012. A little context may be instructive. Having moved from the Bank of Ideas in an occupied UBS office, the School of Ideas was situated in a spacious and attractive school building that had been left vacant for three years prior to its occupation. Two days after this talk the School of Ideas was evicted in a coordinated move with the eviction of the main Occupy London camp at St. Paul's Cathedral (at over four months, the world’s longest running of the 750 camps that sprung up in the wake of Occupy Wall Street, the Spanish Indignados, and the Arab Spring).i Upon eviction, the School of Ideas was immediately bulldozed – a fitting emblem of the wanton destruction that characterises the current round of neoliberal restructuring and public service cuts.

Westminster local authority, just down the road from the School of Ideas, encapsulated the swagger of the new culture in its account of the implementation of cuts to housing benefit: ‘To live in Westminster is a privilege, not a right’.ii Inner London is indeed to be the class-cleansed home of the privileged; a middle class enclave serviced by a newly suburbanised and ever more precarious working class – Westminster’s own figures project that 17 percent of primary school pupils could be forced to move out of the borough.iii Meanwhile, at the other pole, March’s ‘millionaire’s budget’ cut taxation for the rich – those on incomes of £1m will benefit annually to the tune of £42,500.iv No wonder the police and law courts have shifted up a gear in the discipline, punishment and brutalisation of student demonstrators, anti-cuts activists, and the young people involved in the August riots – a move undoubtedly driven by concern that the normalisation of this grotesque inequality can’t hold indefinitely.

In repurposing the vacant UBS office and abandoned school, Occupy London has spun such critical threads as these through neoliberalism, cuts, housing and the city, and has done so in ways both analytical and practical. But the ‘Bank’ then ‘School’ of Ideas has also had a distinct pedagogical dimension. In Chile, California, Britain and elsewhere, direct action against neoliberal education policy has been a leading edge of the current cycle of struggles. These struggles are largely defensive, fighting for the last remnants of a model of liberal education that is far from perfect, albeit that it is vastly superior to the emerging neoliberal model of debt-financed vocationalism. But the composition of this struggle has also been characterised by new critical knowledges and solidarities, as funding cuts in tertiary and higher education, creeping privatisation of educational institutions, student debt and graduate unemployment have drawn together a diverse range of actors that have interrogated the forms, functions and possibilities of education at a new level of intensity. The School of Ideas, like other autonomous educational endeavours, has been interlaced with these developments, due not least to the circulation of participants through educational struggles and Occupy. But it was also something that ‘stood up on its own’, to make use of an expression I discuss below. Equal parts co-learning school, workshop, community centre, organisational base, public interface and home, one might say that the School of Ideas amplified (rather than isolated) the critical intellectual function and culture of Occupy London. The School of Ideas has now gone; ‘Occupy May’ is around the corner.v

Minor Politics

With the UK government itching to criminalise squatting, it’s a real pleasure to be speaking in a building that is undergoing ‘public repossession’, so I’d like to thank Andy Conio for organising this workshop and the School of Ideas for hosting us. What I want to do in this talk is work through three of Deleuze and Guattari’s concepts that are helpful in thinking about Occupy. What do I mean by ‘helpful’? My aim is deliberately not to try and explain Occupy, to sew it up in a theory – that, for Deleuze, would be to negate what is inventive in a movement, but also to lose the inventive quality of theory, making it merely a representation of a state of affairs. Instead my approach will be to use theory to reflect upon certain themes or problems in Occupy, looking at how these problems can be approached with Deleuzian concepts in a way that might help shed light upon them and possibly aid their further development. It’s a recursive relation, for reflection upon Occupy’s themes or problems should also help extend Deleuzian concepts, lending them a contemporary vitality.

Given that this workshop is concerned in equal measure with bringing Deleuze and Guattari’s concepts into relation with Occupy, and with offering an introduction to Deleuze and Guattari as political thinkers, I’m going to try and strike a balance between concept and Occupy, leaving space for us to expand upon the points I make about Occupy in the discussion. The concepts and problems that I address in turn are: minor politics and the 99%, territory, expression and occupation, then, fabulation and agency.

I will start with minor politics and fold in some comments about the 99% – though bear with me, the relation may not at first be apparent. Running throughout Deleuze and Guattari’s philosophy is the notion that politics arises not in the fullness of an identity – a nation, a people, a collective subject – but, rather, in ‘cramped spaces’, ‘choked passages’, and ‘impossible’ positions, that is, among those who feel constrained by social relations.vi This is at once a very immediate, structural experience – let’s say, the experience of poverty, debt, or racism – and also something that is actively affirmed, a continual deferral of subjective plenitude that occurs when people shrug off and deny the seductions of identity and open their perception to what is ‘intolerable’ in social relations; for example, when they ward off the identity of the democratic citizen, the racialised majority, the entrepreneurial self.vii So, what Deleuze and Guattari call ‘major’ or ‘molar’ politics expresses and constitutes identities that are nurtured and facilitated by a social environment, whereas ‘minor politics’ is a breach with such identities, when the social environment is experienced as constraint, as intolerable.

If this is the case, what is the substance of politics? Well, it can no longer be a question of self-expression, of the unfurling of a subjectivity or a people, because in this formulation there is no identity to unfurl, the ‘people’ as Deleuze puts it, ‘are missing’.viii Instead, minor politics is about engagement with the social relations that traverse us, the relations through which we experience life as ‘cramped’ and ‘impossible’. By social relations I mean the whole gamut of economic structures, urban architectures, gendered divisions of labour, personal and sovereign debt, national borders, housing, policing, workfare – whatever combination it might be in any particular situation. In this formulation, the ‘individual intrigue’, as Deleuze and Guattari have it, is ‘immediately’ political, for without an autonomous identity, even the most personal, individual situation is always already comprised of social relations, and vice versa. The deferral of identity is in no way a reduction of singularity, quite the reverse: ‘The individual concern thus becomes all the more necessary, indispensable, magnified, because a whole other story is vibrating within it’.ix

Deleuze uses an appealing image to convey this. He says that to be on the Right is to perceive the world starting with identity, with self and family, and to move outward in concentric circles, to friends, city, nation, continent, world, with diminishing affective investment in each circle, and with an abiding sense that the centre needs defending against the periphery. On the contrary, to be on the Left is to start one’s perception on the periphery and to move inwards. It requires not the bolstering of the centre, but an appreciation that the centre is interlaced with the periphery, a process that undoes the distance between the two.x

Image: Cover of The Occupied Times, Issue 5, 23 November 2011

Now, there is an important propulsive or motive aspect to this minor politics. For rather than allow the solidification of particular political and cultural routes, forms or habits, the practice of warding off identity works as a mechanism to induce continuous experimentation, drawing thought and practice back into a field of problematisation, where contestation, argument and engagement with social relations ever arises from the experience of cramped space. The constitutive sociality of this ‘incessant bustle’ dictates that there can be no easy demarcation between conceptual production, personal style, concrete intervention, tactical development or geopolitical events, and there is plenty of space for polemic.xi It is a vital environment apparent in Kafka’s seductive description of minor literature:

What in great literature goes on down below, constituting a not indispensable cellar of the structure, here takes place in the full light of day, what is there a matter of passing interest for a few, here absorbs everyone no less than as a matter of life and death.xii

I want to make one more brief point before turning to Occupy. I gestured toward a (potentially infinite) range of social relations that minor politics might arise from and engage with, but for Deleuze and Guattari there is a dynamic internal to all of them, the dynamic of capital. Deleuze states:

Félix Guattari and I have remained Marxists, in our two different ways, perhaps, but both of us. You see, we think any political philosophy must turn on the analysis of capitalism and the ways it has developed. What we find most interesting in Marx is his analysis of capitalism as an immanent system that’s constantly overcoming its own limitations, and then coming up against them once more in a broader form, because its fundamental limit is capital itself.xiii

As is abundantly clear in the quotation, Deleuze’s assertion of ‘Marxism’ is not the introduction of a transcendent explanation, but an insistence that we won’t understand the social field or develop effective politics without coming to grips with the contemporary modalities and dynamic structures of the capitalist mode of production, structures that set the conditions through which life is reproduced.

The Grid of the 99%

What has this account of minor politics got to do with Occupy? I want to consider that question through the theme or problem expressed in the Occupy slogan ‘We are the 99%’. It is a problem with a number of component parts. I’ll comment on just two here. ‘We are the 99%’ is an assertion that the vast majority of the world’s population are exploited by and for the wealth of the 1%. It names, in other words, a relationship of exploitation and inequality. And so, to refer to the point I just made about Deleuze and Guattari’s Marxism, the problematisation of capitalism is central. Second, ‘We are the 99%’ simultaneously designates a breach with this relationship of exploitation and inequality. Let me stress that in neither instance does the slogan name a substantial identity. Rather, it at once names and cuts the social relations of exploitation, among those who feel cramped by these relations, feel their intolerable pressure.

This naming and breach in capital is of course very general. ‘We are the 99%’ is something like a ‘formula’ or, to use a term with more spatial connotations, a ‘grid’. It lays out the abstract principle that can be taken up and extended by anyone who would embody or express it in their concrete specificity. In order to see how this grid functions, I want to compare it to one that Occupy is more or less directly opposed to, the grid of parliamentary democracy. Parliamentary democracy is, for Deleuze, a grid laid out across social space that seduces and channels political activity through its specific forms and structures:

Elections are not a particular locale, nor a particular day in the calendar. They are more like a grid that affects the way we understand and perceive things. Everything is mapped back on this grid and gets warped as a result.xiv

Politics in this way gets ‘warped’ as he puts it because everything is reduced to and formatted by the status quo, to the perpetuation of that which gave rise to politics in the first place. A fundamental aspect of this warping is the filtering out of problems of inequality and exploitation from the realms of political interrogation. This was of course Marx’s insight, but the condition is currently so acute that it has widespread, even popular recognition, as Greece and Italy have unelected technocrats imposed on the populace to force through hitherto unknown assaults on living standards, as the ConDems slice up the NHS while claiming that it matters not ‘one jot’ whether it is run by the state or private capital.xv This is why Occupy’s much remarked upon refusal to make demands is so important and so much a product of our times. A demand is a mechanism of seduction into the grid of democratic politics, a means of channelling the political breach with capital right back into the institutions that perpetuate it.

In contrast, the grid that is constituted by the slogan ‘We are the 99%’ is very different. Rather than a mechanism of seduction into the status quo, it is a means of multiplying points of antagonism, or, in more Deleuzian terms, it extends the process of perceiving the intolerable and politicising social relations. This does not occur in general, but from people’s concrete and situated experience – it is a variegated field, where the points of problematisation are housing repossession, the laying waste of public services, privatisation of the commons, debt, police violence, workfare and so on, and the tactics range from occupying social space, through the Oakland general strike, to direct actions against eviction from foreclosed housing, non-payment of debt, the hacking activities of Anonymous, or ‘public repossessions’ as we have in this building. The grid is a catalyst across the social, not an aggregating body extending ever outwards from Zuccotti Park but a zigzag, a discontinuous and emergent process. Again, it’s not a catalyst because people come to recognise themselves in it as an identity – even a collective identity – but because they come to embody and express its problematic.

Before moving on I want to directly address two points that are implicit in what I’ve said so far. First, it is not infrequently said by those involved in Occupy that it is in some sense creating the new world in the shell of the old. That practices of collective decision, direct action, co-operation and care, global association and so on are a kind of communism in miniature. Certainly, all of these collective practices are crucial to understanding the unfurling of Occupy, to its effectivity and affective consistency, to the complex pleasures of being a part of it. But from the perspective, of a minor politics the risk is that Occupy turns inwards, valorising its own cultural forms at the expense of self-problematisation and an ever outward engagement in social relations. Occupy’s vitality lies in its extension and intensification of the problematic of the 99% through an open set of socio-political sites, in what is of course a highly segmented and stratified terrain. For it is in and through these sites that the world’s population exists, and from which an unknown set of possible futures will emerge. To limit those futures to the cultural forms discovered in Occupy camps would be naïve at the least, and risks a conservative reduction of the movement’s potential, a reduction to identity.

Second, refusing to make demands is not a refusal to speak, to formulate and express our anger, hopes and desires. On the contrary, to work through the problems of Occupy requires an incessant production of critical knowledge, knowledge that needs be circulated in the extension and development of these problems. The point is that this knowledge production is immanent to Occupy, not a pleading for recognition from an external power. We have seen Occupy developing slogans and concrete decisions that clearly define what the movement wants, as part of a reflection on how it’s going to get it – and this, of course, is encouraging. But such formulations need to have a minor political ‘efficiency’, they must be adequate to the specific and mutating problems of Occupy and its world, not reproduce themselves at the level of cliché. As Guattari has it, ‘either a minor language connects to minor issues [which should not be taken to mean ‘small’ or exclusively ‘local’ issues], producing particular results, or it remains isolated, vegetates, turns back on itself and produces nothing.’xvi All this knowledge production will involve critique, contestation and the development of divergent positions. Deleuze and Guattari are certainly interested in the way group consistencies emerge from distributed decision – let’s say, the process of ‘consensus’ in Occupy’s General Assemblies – but a good problem is not best extended in thought and practice by pretending that we all agree: ‘The idea of a Western democratic conversation between friends has never produced a single concept’.xvii

Territory and Expression

I will move now to my second main concept and problem – on this and my third point I will be more concise. I want to look at an aspect of the tactic of occupation, specifically the tent, and explore the relation to Deleuze and Guattari’s concepts of ‘territory’ and ‘expression’.

The tent is first of all a practical object. It enables space to be taken and held for a certain duration. In this respect it has a family resemblance to the tripod as was used by Reclaim the Streets in the 1990s, an object that worked at once to cut the flow of traffic and act as a catalyst in the occupation of a road and the emergence of a street party. In Deleuzian terms, both tent and tripod play a part in ‘deterritorialising’ the space in which they operate – that is, in undoing the patterns of behaviour, laws, sensory structures and economic forms that determine that space as a road, stage for commerce or park. But if the tent and tripod deterritorialise in this way, they simultaneously generate a new territory, they re-territorialise into an Occupy camp or a street party.

To construct such a territory is of course difficult. It requires considerable knowledge of the territory that is to be undone: the law, movements of traffic, an intuition about likely police tactics, potential solidarities and enmities of the locale and so on. The constructed territory is thus a finely balanced constellation and can be easily botched. Things in London might have been different, for example, if Paternoster Square hadn’t been barred and Occupy had not instead ended up on land owned by the Church.

Image: Anonymity keeps you warm

But let’s turn to consider the characteristics of Occupy’s territory. Deleuze and Guattari make a rather intriguing argument that the construction of territory goes hand in hand with art, that art is a question of home or habitat: ‘Perhaps art begins with the animal, at least with the animal that carves out a territory and constructs a house.’ Such territory is functional, of course, but it is simultaneously sensory and expressive, that is, artful: ‘the territory implies the emergence of pure sensory qualities, of sensibilia that cease to be merely functional and become expressive features, making possible a transformation of functions.’xviii One can see these tangled aspects of habitat and expression in the ‘art’ of the bowerbird.

What are the components of this constructed territory? Well, they are drawn from the environment, from existent materials – in the case of the bowerbird, twigs, berries, bottle tops – but they are also qualities and forms that emerge in the process of construction:

This emergence of pure sensory qualities is already art, not only in the treatment of external materials but in the body’s postures and colours, in the songs and cries that mark out the territory. It is an outpouring of features, colours, and sounds that are inseparable insofar as they become expressive.xix

The St. Paul’s Occupation is very much this kind of constructed territory. It comprises practical materials, the tent of course, items of furniture, cooking equipment – but also placards and signs, books, newspapers, drums, assemblies, hand signals, the people’s mic, photographic images, livestreams, YouTube clips, the OccupyLSX website and Twitter feed, and so on. My point is not to proclaim that Occupy is ‘art’ exactly, but to suggest that alongside the practical tactics of occupation, the construction of territory through these functional components also includes an expressive, sensory quality that becomes an inseparable aspect of the Occupation.xx This is one explanation, for instance, of the production of newspapers at the Occupy camps, when online production and distribution is clearly more practicable. As well as being an object of news and practical politics, the newspaper in this regard is also a bloc of sensation, an aesthetic expression of Occupy.

Tent as Monument

You might ask, ‘what’s the relation between this sensory or expressive quality of Occupy and its meaning or explicit politics?’ For Deleuze and Guattari the two are different modalities of composition that come into a mutually sustaining encounter. They sometimes use a peculiar word for these works of art or works of territory – they call them monuments:

the monument is not something commemorating a past, it is a bloc of present sensations that owe their preservation only to themselves and that provide the event with the compound that celebrates it. The monument’s action is not memory but fabulation. […][It] confides to the ear of the future the persistent sensations that embody the event: the constantly renewed suffering of men and women, their recreated protestations, their constantly resumed struggle.xxi

So, the monument, the bloc of sensation, celebrates the event of which it is a part. In our case, it celebrates the suffering and struggle that is named and enacted by the slogan or grid of the 99%.

I have mentioned the range of artefacts that constitute the work of territory, the monument, but the tent is a special case. It is of course a habitation, that’s what distinguishes it from the tripod I mentioned earlier. As habitation it has great tactical value in the endurance of Occupy, even through the winter. But it also comes with particular sensory associations or expressive qualities. A tent pitched in the inner city conveys something of the fragility of life, the precariousness of existence – ‘bare life’, if you will, an impersonal quality of all life. And this impersonal, precarious life is filtered in our time through the specific condition of homelessness, as soaring rents, mortgage foreclosures, evictions, benefit and wage cuts, debt and unemployment tip the home into a state of crisis. Indeed, as we’re seeing with the rise of ‘tent cities’ in the US, the tent has become a very real habitation for a considerable volume of displaced people – including people at Occupy St. Paul's and elsewhere: ‘a part of the homeless has become Occupy London, and a part of Occupy London has become the homeless.’xxii

This quality of life – fragile, impersonal, damaged – is central to the tent as monument, lifting ‘suffering’ to the level of aesthetic expression without losing any of its ‘struggle’. Even in its expression of suffering, then, the tent is not an abject object. But it also conveys a rather joyous quality of mobility. At risk of playing to a cliché, it is the dwelling of the nomad so dear to Deleuze and Guattari, where dwelling is part of an itinerant process, tied not to land but subordinated to the journey – the production of a ‘movable and moving ground’ through ‘pitching one’s tent’ (the deliberately processual quality of Occupy is plain for all to see).xxiii With the tent, then, we see something of the tactical or practical aspect of Occupy interlaced with its sensory or expressive quality, a tactic and a sensory bloc – both, for Deleuze and Guattari, are constitutive of its territorial form.

Image: Making a 'We are the 99%' banner at the School of Ideas

The nomadic tent orients our attention to a final aspect of the territory of Occupy. As well as constituting its territory, Occupy needs also to be open to a degree of deterritorialisation of its own. What does this mean? You can think of deterritorialisation here as the spatial dimension of that opening to the social which I began with, the process of warding off identity and problematising social relations. It is a central problem for Occupy, as perfectly expressed in an editorial of The Occupied Times:

[The eviction of OWS from Zuccotti Park] triggered a period of self-examination about how the Occupy movement might best move forward beyond its signature tents and into communities, enacting the movement’s core message through practical action rather than symbolism. It is a journey that has seen American occupiers leave tents behind in favour of defending the homes of those about to be foreclosed. […] Thanks to equal measures of adroitness and serendipity, Occupy London’s initial encampment at St. Paul’s Churchyard has now far outlived Zuccotti Park in duration. […] It would be a bitter irony – and a failure of enormous proportions – if we allowed our comparative security to stop us seeing some of our more distinctive tactics for what they are: a tool to be employed only for as long as they remain useful. Useful tactics generate change. They inspire others to act. To do that we must look outwards.xxiv

This process of deterritorialisation concerns not only the dynamics of the one territory, but also the relation or reverberation with other territories. The obvious example is the relation with St. Paul’s itself. There’s a clear sense in which Occupy subjected St. Paul’s to a force of deterritorialisation, this minor monument undoing at the borders Wren’s rather more major monument and the Church’s structures of authority. Hence we witnessed Giles Fraser’s resignation and Occupy’s forcing of the Church to reflect upon the politics of Christianity and its relation to the City’s banks. In turn, this strange reverberation between Occupy and St. Paul's had some effect on the territory of the popular imagination, if we can call it that, even on its media representation. The obvious hypocrisy of the Church in its initial dealings with Occupy seemed to lift and project the image of Occupy in the popular imagination, lending it a degree of sympathy and support that it may not have had if it had been in a straight face off with bankers and police (for, despite all that we have witnessed since 2008, when the lines are drawn between police and resistance in this way, common sense, ever re-charged by news media, unfortunately still tends to prostrate itself to the truths of authority).

There are of course other points and possibilities of reverberation: other Occupy camps, the hacker cultures, precarious workers, rootless graduates, assailants of workfare, those involved in education campaigns, and so on. The aim of Deleuzian theory would be to consider the specific qualities or features of these interlaced points, all of them groping toward some sort of patchwork of politicised relations.

Fabulation and Agency

Thus far I have worked through two sets of concepts and problems: minor politics and the 99%; and territory and occupation. I want to end now with a brief sketch of a third concept and problem. This is Deleuze and Guattari’s concept of myth or fabulation and the problem of the collective agency of Occupy. In theory circles at the moment and in some commentary on Occupy there are indications of a return to voluntarism, with talk of the people’s ‘will’ as driver of change. From a Deleuzian perspective, voluntarism abstracts a pure subjectivity from what are in fact multiple levels of subjective determination (economic, libidinal, semiotic, organisational, etc.), and so fails to ascertain where politics comes from or to address why subjectivity – or ‘will’ – tends more usually to repress itself. Deleuze and Guattari would counter this voluntarism with the minor political emphasis on practical problematisation that was the focus of the first part of this talk – political composition not formed of a generic quality of human being, but arisen from the specific material conditions of ‘the present state of things’, as Marx has it. But there is an additional aspect of Deleuzian philosophy that is helpful for getting at the issues of collective agency or force that those who appeal to the people’s will are, rightly, interested in.

Concepts, problems, territories and so on are constructed by their participants in the kinds of ways that I have been discussing. But they also have a self-positing character – they are created by participants, and they simultaneously create themselves, they have a life of their own: ‘Creation and self-positing mutually imply each other because what is truly created, from the living being to the work of art, thereby enjoys a self-positing of itself, or an autopoetic characteristic by which it is recognized’.xxv

This isn’t easy; most created entities collapse without becoming self-positing. But if an entity does achieve this, if it can ‘stand up on its own’, as Deleuze and Guattari put it, then you have something interesting, something with an agency all of its own.xxvi You have a revolution, an artwork, a concept, or in our case, you have the Occupy movement. What does it mean to say that Occupy is self-positing? It means that as well as being generated by the people, tactics, objects, slogans, sounds and so on that are a part of its territory, it also takes on a life of its own, a life that pulls its constituent parts along, creating them as parts of its event.

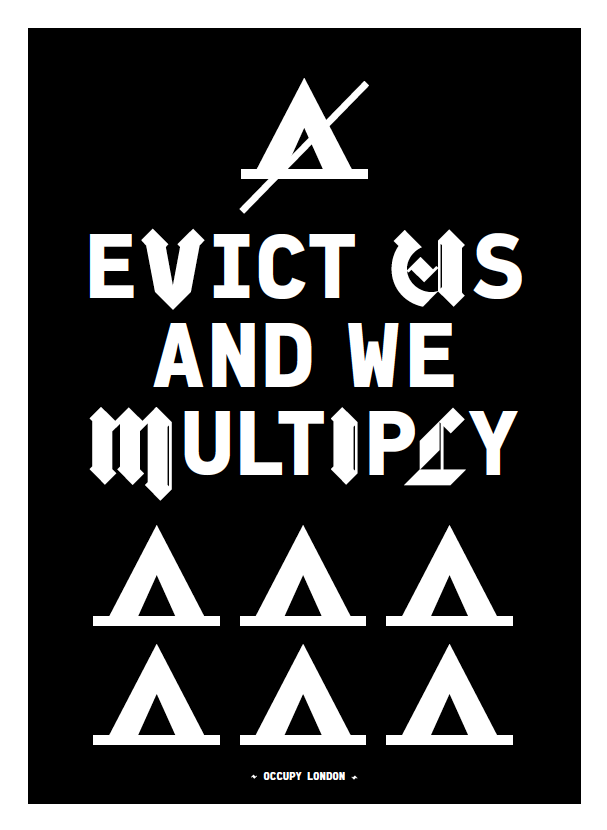

Image: Occupy London poster

Now, when Deleuze and Guattari discuss this self-positing process in the context of politics, they sometimes describe it as a process of ‘fabulation’. It’s a word you might have noticed earlier in the quotation about the monument. Fabulation or myth-making occurs when the shock of an event – be it an earthquake, a work of art, a social upheaval – produces visions or hallucinatory images that substitute for routine patterns of perception and action and come to guide the event. In Deleuze and Guattari’s reading, fabulation is a weapon of the weak, a means of fabricating ‘giants’, as they put it – germinal agents with real world effects in the service of political change.xxvii What is perhaps most appealing in the context of Occupy is that these fabulations or myths are not so much located in individual people – the cults of personality, for instance, the Lenins, Maos, Churchills, what have you – but have a desubjectified or anonymous quality, generated and held in the fragmented bits of events, stories, medias, affects and material resources, and are associated as much with ‘mediocrity’ as with the grandiose.xxviii In this way Deleuze describes myth as a ‘monster’, it ‘has a life of its own: an image that is always stitched together, patched up, continually growing along the way’.xxix

Occupy has something of this mythical quality, an agential power of its own that exists among and between us, and that pulls its particularities along. I’ll end by pointing to one small (and by no means unproblematic) artefact in this myth: the Guy Fawkes mask. Think how different these two images of political myth are. Mao, a concentrated myth centred on an individual and the truth of his infallible thought. And the Guy Fawkes mask, an anonymous, distributed power – a part of the myth of Occupy, open to anyone, signifying a resistance to closure in a leader, vaguely menacing, a little bit silly, mediocre even, and pop cultural to boot. The mask’s impersonal mythical power is well expressed in a cartoon in The Occupied Times, a cartoon that takes its words from Subcomandante Marcos and so forms a red thread across to another political myth of our time: it’s not ‘who we are’ that’s important, but ‘what we want’, ‘everything for everyone’.xxx

Nick Thoburn <N.Thoburn@Manchester.ac.uk> lectures in sociology at the University of Manchester. He is the author of Deleuze, Marx and Politics (Routledge, 2003) and is currently writing a book on the forms and cultures of independent media

Footnotes

i‘Occupy protests around the world: full list visualised’, http://linkme2.net/s7

iiWestminster council press officer quoted in Amelia Gentleman, ‘Housing benefit cap forces families to leave central London or be homeless’, The Guardian, 16 February 2012, http://linkme2.net/s6

iiiIbid

ivPatrick Collinson, ‘Budget 2012: earning £1m? Your tax cut will pay for a Porsche’, The Guardian, 21 March 2012, http://linkme2.net/s5

vThis article introduction was written in April 2012. See http://occupylsx.org/

viGilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, Kafka: Towards a Minor Literature, Dana Polan (trans.), Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1986, pp.16-17; Gilles Deleuze, Negotiations, Martin Joughin (trans.), New York: Columbia University Press, 1999, p.133.

viiI develop this ‘minor politics’ at length in Deleuze, Marx and Politics, London: Routledge, 2003.

viiiGilles Deleuze, Cinema 2: The Time-Image, Hugh Tomlinson and Robert Galeta (trans.), London: Athlone, 1989, p.216.

ixOp. cit., p.17.

xGilles Deleuze with Claire Parnet, Gilles Deleuze: From A to Z, Pierre-André Boutang (dir.), Charles Stivale (trans.), Los Angeles: Semiotext(e), 2012.

xiFranz Kafka, The Diaries of Franz Kafka: 1910-23, Maz Brod (ed.), Joseph Kresh and Martin Greenberg (trans.), London: Penguin, 1999, p.148.

xiiKafka quoted in Deleuze and Guattari, op cit., p.17

xiiiDeleuze, Negotiations, op. cit., p.171.

xivGilles Deleuze, Two Regimes of Madness: Texts and Interviews 1975-1995, David Lapoujade (ed.), Ames Hodges and Mike Taormina (trans.), Los Angeles: Semiotext(e), p.143.

xv‘To be honest I don’t think it should matter one jot whether a patient is looked after by a hospital or a medical professional from the public, private or charitable sector’, Tory Health Minister Lord Howe, quoted in Nick Triggle, ‘Private Sector Have Huge NHS Opportunity’, 7 September 2011, http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-14821946

xviFelix Guattari, Chaosophy, Sylvère Lotringer (ed.), New York: Semiotext(e), 1995, p.37.

xviiGilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, What Is Philosophy?, Hugh Tomlinson and Graham Burchill (trans.), London: Verso, 1994, p.6.

xviii Ibid., p.183.

xixIbid., p.184.

xxThe bowerbird is certainly not the last word on ‘art’ in Deleuze and Guattari. Despite possible indications to the contrary here, their writing on art is not best viewed through the avant-garde lens of the subsumption of art and everyday life, for they invest considerable import in the exacting forms and techniques of modernist practice, in painting and cinema especially. See Simon O’Sullivan, Art Encounters Deleuze and Guattari: Thought Beyond Representation, London: Palgrave, 2006, and Stephen Zepke, Art as Abstract Machine: Ontology and Aesthetics in Deleuze and Guattari, London: Routledge, 2005.

xxiWhat Is Philosophy?, op. cit., pp.167-8, 176-7, emphasis added.

xxii'Occupy London Homelessness Statement’, http://theoccupiedtimes.co.uk/?p=2594

xxiii What Is Philosophy?, ibid., p.105. Many thanks to John Bywater for pointing out this passage on the ‘English’ taste for camping, which helps counter any orientalism in Deleuze and Guattari’s concept of nomadic dwelling.

xxiv The Occupied Times no.8, p.2, http://theoccupiedtimes.co.uk/?p=1744

xxv What Is Philosophy?, op. cit., p.11.

xxvi Ibid., p.164.

xxvii Ibid., p.171.

xxviii Ibid., p.171.

xxix Deleuze, Cinema 2, ibid., p.150; Deleuze, Essays Critical and Clinical, Daniel W. Smith and Michael A. Greco (trans.), Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1997, p.118.

xxx The Occupied Times no.6, p.2, http://theoccupiedtimes.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2...

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com