Unlimited Liability or Nothing to Lose?

A structurally adjusted version of an article first written for Wildcat magazine in April 2011, in which Clinical Wasteman considers crisis management in the world’s most ‘financialised’ and therefore most state-permeated economy – the UK

April 2011. The UK government, responding to business concern at its plan to impose a fixed limit on non-European immigration, quietly announces some concessions. Permanent residence will be open to anyone bringing £5 million into the country or able to borrow the same amount from a British bank, secured on assets held elsewhere. A trivial adjustment of migration policy, but an eloquent statement of the idea of ‘national prosperity’ underlying ‘post’-crisis economic management. The priority is ‘controlled’ reflation of the pre-crisis economy of private credit circulation, appreciating asset prices and associated services along a spectrum from financial to menial.

But no asset boom can be reflated without backing from wholesale asset handlers (misleadingly collectivised as ‘markets’), an affinity group whose internationalism (for purposes of arbitrage) and political intransigence the left might learn from. The demands are familiar because they never change: protection of creditors, ‘flexiblity’ of capital and labour markets, and transfer of the resulting risk (or liability) to the non-asset-owning class. In practice this calls for a show of intent to cut down without harm to asset prices the fiscal deficit and public debt swollen by the state’s assumption since 2007 of an unpayable £250bn+ debt overhead contracted by... private asset wholesalers.

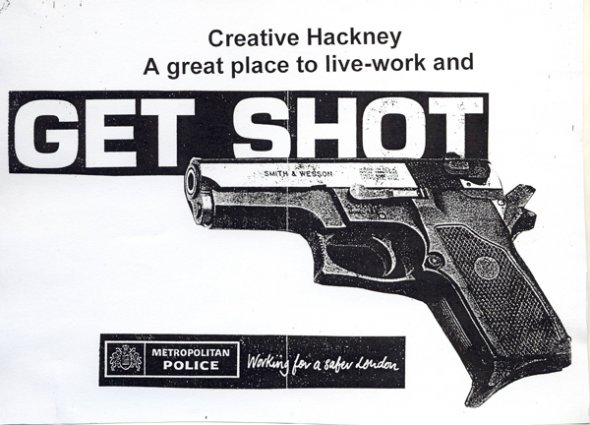

The ‘savings’ are supposed to be made by scaling back the state’s role as employer of last resort and welfare provider to the large part of the population which the asset boom economy was never able profitably to exploit. But, cutting cash payments to the working class is by no means the same thing as ‘shrinking the state’. Any government expecting to maintain order while removing millions of people’s legal means of social reproduction must prepare at the same time for expansion of the core state function: policing in the broadest sense. One way of stating the stakes of the current and imminent struggles would be to ask: what kinds of ‘disorder’ (individual-‘criminal’, ‘racial’-sectarian, class-based?) will the state be forced to police, and how successful will the policing be?

The expression ‘privatisation of debt’, used by some leftists to describe the general policy trend in the UK and elsewhere, is accurate if understood in a double sense. On one level it refers to the transfer of the pre-crisis financial debt overhead from the private sector to the state and onward to the working and assetless class; on another, to the advertised purpose of the effort, the idea that lifting the public debt burden (or rather dumping it downwards) will somehow clear the way for renewed growth of a private sector centred on the creation, expansion and monetisation of credit, i.e. debt.

The inability of this method to restore long term accumulation is obvious enough that various Marxists, shock therapy monetarists, conservative Keynesians and neo-Keynesian radicals are all able to prove it to their own satisfaction. But questions of long term accumulation have little to do with the time scale on which ‘policymakers’ (consultants, senior civil servants and government) and businesses operate.1 On the ‘pragmatic’ level of social management and shareholder value, administrators find little alternative to short term reflation of the credit/service economy, given the (mutually hostile) disruptive capacities of one class with everything staked on the asset boom and another kept dependent on its crumbs. Such is the existing concentration of capital in the FIRE (finance, insurance, real estate) sector and ancillary services that the kind of manufacturing oriented ‘rebalancing’ demanded by unions and occasionally promised by ministers would wipe out much of the ‘wealth’ circulating through service and consumer markets, provoking international capital flight and alienating the ‘aspirational’ or ‘hardworking’ demographic knitted tightly into FIRE sector dependency through home and small business ‘ownership’, private pensions and personal financial investment, compromising years of effort to divide this group from the ‘feckless’ proletariat singled out for attack under the present policy.2

The political basis of credit reflation is one reason for emphasising it; another is that the perspective of debt privatisation connects the stakes across the imaginary line between ‘public’ and ‘private’ sectors. This matters because official reduction of the scope of conflict to the ‘public sector’ – an agenda accepted by unions and many ‘anti-cuts’ campaigners – is an aggressive tool of class decomposition, mobilising ‘aspirational’ worker-consumer opinion against the supposed ‘privileges’ of state employees and welfare claimants. The inadequacy of ‘defending the public sector’ as a form of social counterpower will be ever more obvious over the coming months: the 500,000 state workers slated for redundancy will be ‘inside’ the private sector from the moment they encounter private welfare contractors, as well as in any future employment, which may anyway be the same work they used to do, sold back to outsourcers on freelance or agency terms.

The reflationary side of debt privatisation is visible on a headline story, macro policy level, while the punitive side – the downward transfer of liability – stretches all the way down to the pettiest micro interventions. (The present government follows its predecessor in an obsession with Behavioural Economics, and has set up a dedicated ‘Behavioural Insight Team’ to propagate ‘social norms’, i.e. psychological reflexes of individual liability for social problems.) On the macro level the reflationary and punitive aspects intersect almost everywhere, most obviously in the overall scale of fiscal spending cuts (£83 billion), their concentration in working class ‘entitlements’ (welfare, education, and municipally administered services such as care for children/elderly/disabled), and the avowed reliance on monetary stimulus (a former oxymoron which officials have learned to utter earnestly) to offset the ensuing contraction of demand.3Other important elements include:

– Transfer of additional tax burden onto low-end consumption through a VAT increase to 20 percent, as part of a general adjustment of the tax system in favour of national competitive advantage in international arbitrage. (As with the public spending cuts, the effect is supposed to be compensated for by low interest rates: i.e. offset for homeowners in particular.)

– Automatic enrolment (with a small print ‘opt out’ provision) of private sector workers in NEST, a stock market pension scheme.

– Further replacement of direct state handling of those facilities regarded as politically unfeasible to shut down altogether (e.g. welfare, garbage collection, medicine) with state funded ‘commissioning’ of outsourced contractors, i.e. transfer of captive markets to leverage financed ventures. The most ambitious move in this direction may be the reconstitution of the National Health Service as a wholesale buyer of services from ‘any willing provider’. Among the first ‘providers’ to come forward was accountancy and consultancy multinational, KPMG, indicating both the scale of the prizes available and the scope for sub-sub-contracting.

– A housing reform package openly relished as the urban equivalent of ‘Highland Clearances’ by some plain speaking Tories. Drastic reduction of housing benefit (rent subsidy paid through the welfare system) and the increase of ‘social’ (outsourced ex-public) sector rents to 80 percent of market level must be seen as a renewal of a consistent 30-year policy drive to transfer working class income into the private real estate market, i.e. one of the main long term factors in the pre-crisis FIRE bubble and the crisis itself. Political determination to revive this process is also evident in the relaunch of ‘Enterprise Zones’: the system of subsidised and unregulated urban clearance and redevelopment with which the Thatcher administration began the 30-year cycle.4

Other aspects of social punishment, overlapping with those already mentioned in some cases and less widely reported in others, contribute less obviously to reflation or even to fiscal savings; these can be understood as extracting ‘payment for the crisis’ in a disciplinary rather than monetary sense, or more practically as cultivating the mix of personal desperation and aspiration that a credit-service economy requires of its workers, i.e. the ‘basic skills’ or ‘life skills’ whose absence business lobbyists perpetually lament. Examples include:

– Massive transfer of sickness benefit claimants onto the dole and the aggressive ‘workfare’ programmes attached to it, substantially increasing the number of forced competitors for what all institutional forecasts agree will be a static or falling number of jobs.

– Similarly intensified competition between individual workers outside the welfare system: e.g. public and private sector employers forcing all employees to reapply simultaneously and competitively for reduced numbers of jobs on downgraded terms. Among others, 170,000 municipal workers across the country face an immediate ultimatum to sign new contracts or be fired. (Plus a government promise perfectly encapsulating Behavioural Economists’ ideal of ‘fairness’: all young people will have the opportunity to work as unpaid interns.)

– Abolition of legal aid (means tested state contribution to legal fees) for employment, welfare, housing, immigration and clinical negligence cases, i.e. exactly the kind of disputes likely to proliferate in the near future.

– Introduction of fees and access restrictions for employment tribunals (legally binding hearings on unfair dismissal, discrimination etc.); repeal of a large amount of workplace safety law, with funding cut by 35 percent for the body enforcing the remainder; exemption for small businesses from labour legislation. These latter measures reward years of business lobbying and are accompanied by an ‘Employer’s Charter’ ‘reminding’ bosses of their ‘right to ask workers to take a pay cut’.

The same deployment of punitive logic at administrative level is also visible in programmes of marginal scale and ideas yet to be fully implemented:

– A food voucher scheme (run by a Christian charity) for recalcitrant dole claimants whose money is cut off, making it easier for ‘welfare-to-work’ contractors to stop the payments and hastening the convergence between the general welfare system and the openly ‘deterrent’ voucher based mechanism for asylum seeking migrants.

– A gap in the all round system of state support for real estate accumulation closed at last by legislation to criminalise squatting, disingenuously helped along by The Evening Standard’s stories about immigrants trying to squat already inhabited buildings. Displacing an existing occupier is of course already illegal, but the image of Baltic squatters exploiting ‘soft touch’ British law in their own sort of international arbitrage gave the panic a momentum of its own.

– A government commissioned Deloitte report recommends compulsory online transactions in all personal interaction with the state (benefit claims, document applications, fee payments), on the grounds that contributing to cutting ‘back-office costs’ (i.e. wages of letter openers and call centre workers) is a universal social duty. An all online system would also help to subsidise financial reflation, in that replacement of the former clerical labour would be contracted to the overlapping financial/IT consultancy/services sector (e.g. Deloitte).

– A major speech by David Cameron modifying, though by no means softening, the use of anti-immigration sentiment for purposes of class decomposition. The welfare system, he declared, is ‘to blame for creating a generation of work shy Britons, allowing migrants to take jobs.’ Thus the pretence that immigration control is about protecting native labour from foreign competition is dropped altogether, at the same time as the social undesirability of foreign workers is raised to the level of a self-evident premise. Foreign proletarians are intrinsically a problem, and ‘lazy’ British members of the same class are to blame for it: therefore the burden of punishment must fall on both. The stakes of this shift in emphasis are high: will it deepen hostility between ‘British’ and ‘foreign’ workers as the former blame the latter not only for ‘stealing jobs’, but also for the punitive attacks of state and capital, or might the promise of punishment for all actually contribute to elementary, self-interested solidarity across different ‘nationalities’ in the same material position?

In April, this account was attached to a description of the social counterpowers then trying to spoil the management model. Because the social work of spoiling is ongoing and volatile, a report on where it stood six months ago is pointless now. But the policing plan has run unchanged through months of bathetic protest gestures and untranslatable riots. In October, the uninventably named Lord Chief Justice Lord Judge threw out the first appeals against post-riot prison sentences, and in so doing explicitly invoked the collective nature of the offences as the reason for spectacular punishment:

The reality is that the offenders were deriving support and encouragement from being together with other offenders and offering comfort, support and encouragement to the other offenders around them. Perhaps too the sheer numbers involved may have led some of them to believe that they were untouchable.

The Clinical Wasteman is certified Hard To Reach. A true address is just somewhere snipers count heads

This article continues the analysis of UK austerity struggles:

Footnotes

1 Keynes’ ‘in the long run we are all dead’ has been quoted often since the crisis broke out, with little overt acknowledgement that the lifespan implied in business and political strategy has contracted since the mid-20th century from human to something more like feline.

2 (From a forthcoming dictionary):

Aspiration | aspirational. The invention of the highly elastic adjective ‘aspirational’ coincides with what until recently looked like a permanent shift in the scope of the noun ‘aspiration’. Samuel P. Huntington, in his 1973 rant to the Trilateral Commission, deplored ‘aspiration’ as an extravagant and dangerous collectively staked claim: an overeducated underclass demanding too much and expecting to get it by forcing structural change. But by the time of its emergence in the 1990s as a party-political marketing theme, ‘aspiration’ implied a strictly personal kind of anxious conformism. The ‘aspirational’ individual stakes everything on ‘social mobility’; that is, she expects to compete against the rest of her class on a ‘level playing field’ (i.e. everyone doing the same thing), and she expects to ‘win’, beating her opponents ‘fairly’ by embracing more eagerly, energetically and obediently whatever ‘rules of the game’ are transmitted from above. Or, better still, by correctly guessing in advance the instructions likely to be dictated by previous ‘winners’ occupying higher rungs on an imaginary ‘career ladder’ (comprised in turn of ‘playing fields’ at ever higher altitudes). This form of pre-emptive obedience is known as ‘showing initiative’. The curious elasticity of ‘aspirational’ as an adjective lies in its multiple applications to a prize (an ‘aspirational’ apartment, home entertainment system, lifestyle), the competitors pursuing it (see above), and the wider social structure imposing the competition (an ‘aspirational society’). This last usage confirms the irreconcilable contradiction between ‘aspirational’ conditions and the kind of aggressive class ‘aspiration’ feared by Huntington. Diligent ‘aspirational’ behaviour precludes the very thought of provoking structural change, as the existing structure is the context, vehicle and measure of personal ‘success’; turning the world upside down would make a mockery of the effort to ‘rise to the top’.

3 In the sub-zero-sum game of traditional capitalist crisis management, ‘stimulus’ always referred to fiscal policy: the state spending money raised through borrowing or sometimes even taxation in ways thought to ‘stimulate’ (hence the name) production or just consumer demand. Monetary policy – central bank manipulation of the number of currency units chasing each commodity – was preferred by opponents of stimulus. The hybrid monster ‘monetary stimulus’ slinks into view when fiscal spending is political poison but ‘Something must, nonetheless, be Seen To Be Done’. In practice, this means ‘grassroots’ borrowing becomes compulsory as newly conjured euros/dollars/pounds flood the credit system and erode the value of cash. If all goes well (in a world of international competition) the inflation – along with the ‘stimulus’ – flows with the fresh hot money out of the stimulant states and into high yielding ‘emerging markets’.

4 On the new Enterprise Zones plan in relation to the old see, Stephen Alexander, ‘Enterprise zones introduced across England’, http://www.wsws.org/articles/2011/apr2011/zone-a26.... On the old ones in relation to State-led ‘leveraging’ of real estate opportunities, see Anna Minton, Ground Control, London: Penguin, 2009.

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com