Free speech and the ‘snowflake’

If, as advocates of free speech would have it, to speak the truth is to necessarily cause offence, what, asks Keston Sutherland, is the origin of the threat posed by the ‘snowflake’?

On 4 February 2018 an article by Steven Pollard appeared in The Daily Mail under the headline ‘Snowflakes? They’re today’s fascists!’ The article begins with Pollard relating that he had commemorated Holocaust Memorial Day the previous weekend. He says that in his role as editor of The Jewish Chronicle he is ‘confronted daily with the legacy of that unique evil’, the Holocaust, a legacy which he says includes ‘the suppression of debate, the distortion of truth and even the burning of books’. ‘I know, too’, he adds, ‘that the Third Reich’s totalitarian impulse – that only one type of question and one type of answer are legitimate, and all else must be extinguished – is far from unique because repressive regimes the world over continue to ban freedom of enquiry and freedom of expression.’ Pollard then briskly cites the attempt by students at UWE to disrupt a talk on their campus by Jacob Rees-Mogg the previous Friday as an example of the chilling re-emergence of the totalitarian impulse of the Third Reich, before declaring that the culture of public debate at large is currently in peril due to what he calls an ‘avalanche’ of snowflakes. The word ‘snowflake’ is the most fashionable new addition to the contemporary popular political lexicon. Since the GOP hustings in the run up to Trump’s election in 2016 and the European Union Referendum Act of 2015 that would lead to the Brexit vote in 2016, this word and its hazy cluster of accusation has been on millions of snarling lips both in the commentariat and in the general public. Pollard reports with a titillating touch of exasperation that ‘snowflake’ has even been exalted into the definitive record of the national language: history has required that this phenomenon be granted an entry in the indelible Oxford English Dictionary. The complete draft entry for ‘snowflake’ in the OED, added in January 2018, is as follows:

Snowflake: orig. and chiefly U.S. (usually derogatory and potentially offensive). Originally: a person, esp. a child, regarded as having a unique personality and potential. Later: a person mockingly characterized as overly sensitive or easily offended, esp. one said to consider himself or herself entitled to special treatment or consideration.

Pollard, or his editor at The Daily Mail, trims away the fussy prepositional specification ‘mockingly characterized as’ and gives only the character itself: ‘a snowflake’, he writes, ‘is ‘an overly sensitive or easily offended person’’. The first recorded use of the word in this later, derogatory sense is credited by the OED to Chuck Palahniuk, the American novelist whose macho, pseudo-existentialist fantasy Fight Club contains what has become the aphoristic sentence: ‘You are not a beautiful and unique snowflake. You are the same decaying organic matter as everything else, and we are all part of the same compost pile.’ Readers who have put up with Schopenhauer will recognise right away this old style of dark, bullying vilification and the generic vector of its suction, the point of which is to drag the reader out of his fantasy of happiness and optimism by assaulting him with hatred and derision. The reader must be rescued from the narcosis of life and optimism by being intoxicated with death and pessimism. The ‘snowflake’, brutally denigrated by the tough guy Chuck Palahniuk with what is supposed to be the patently risible pair of adjectives ‘beautiful and unique’, is told that he is nothing but a cosseted little fiction, a pampered daydream, and the best or only way to get this through to him is to do what Chuck Palahniuk and his readers get a kick out of doing to themselves – that is, to rub his freshly scrubbed little face in the shit that is all anyone really is. The snowflake can only be disabused by being abused; the remedy for sensitivity is sadism.

How are we to make sense of this fantasy of the snowflake and why is it currently so seductive to so many people on the right and far-right of the political and cultural spectrum? At first sight, the structure of aggression appears simple enough. The basic Kleinian model of projection seems like it will probably cover all the angles. The fantasy of a figure who is too sensitive and too easily offended plainly serves the function of a container or screen for a hostile projection of a part of the self that wants to direct its sadism outwards, away from itself. The snowflake grates on the nerves and offends the moral sensibility of the person who tells himself that he is not so sensitive or so easily offended, usually because he has to live in the real world; he cannot afford to be so sensitive, he says, and he was never allowed to be upset so easily, because of how things really are. The containment of self-pity is effective enough to sustain the projection and also, crucially, ineffective enough to let at least a little self-pity spill out, without yet blowing up the entire dam. The outrageously sensitive snowflake can be ‘used as a container for […] unwanted and problematic aspects of the self’, to quote a recent, handy formulation of the Kleinian model by Farhad Dalal.1 Simply put, the belief that you are too sensitive and too easily offended licences me to be too sensitive and too easily offended, by you. I am outraged because you are so easily outraged: it’s your fault. Really of course I want to be very sensitive and to be outraged by every least thing, since I really am. You, the snowflake, allow me to be that person who I really am, by hating him, in the form of you.

But this straightforward use of the concept of projection invites direct rebuttal and seems unlikely to get us very far toward specifying the detailed content of the fantasy. We need also to tarry with the manifest content, or what angry and dyspeptic people on the right say is dangerous about the oversensitivity of others. The charge is invariably the one repeated by Pollard, invariably in an oracular idiom full of warnings that is meant to impress upon the reader that the objection to oversensitivity is not mere anxiety or disgust, but that it has been formed under the inevitable gravity of serious moral and historical reflection. The objection is always that the snowflake is a threat to free speech. ‘Theirs is a dangerous delusion’, Pollard gravely warns, ‘because free speech – and the offence which can come with it – is the bedrock of freedom itself.’ What idea of free speech is this? The syntax of Pollard’s warning is the normal one, and it gives the basic structure of the antipathy in its manifest form. Free speech ‘– and the offence which can come with it –’ is the bedrock of freedom. The conjunction is presented as a parenthetical addition that however must imperatively be insisted on: we cannot say what free speech is without right away adding that giving offence is or may be essential to it. This addition is invariably made as though with a sad presentiment of its being resisted, as if to suggest that, however painful or uncomfortable it may prove to be for you, nonetheless I must say whatever I must say, in essence because it is my moral and historic duty, and your role, likewise a moral and historic duty, is to be made to listen.

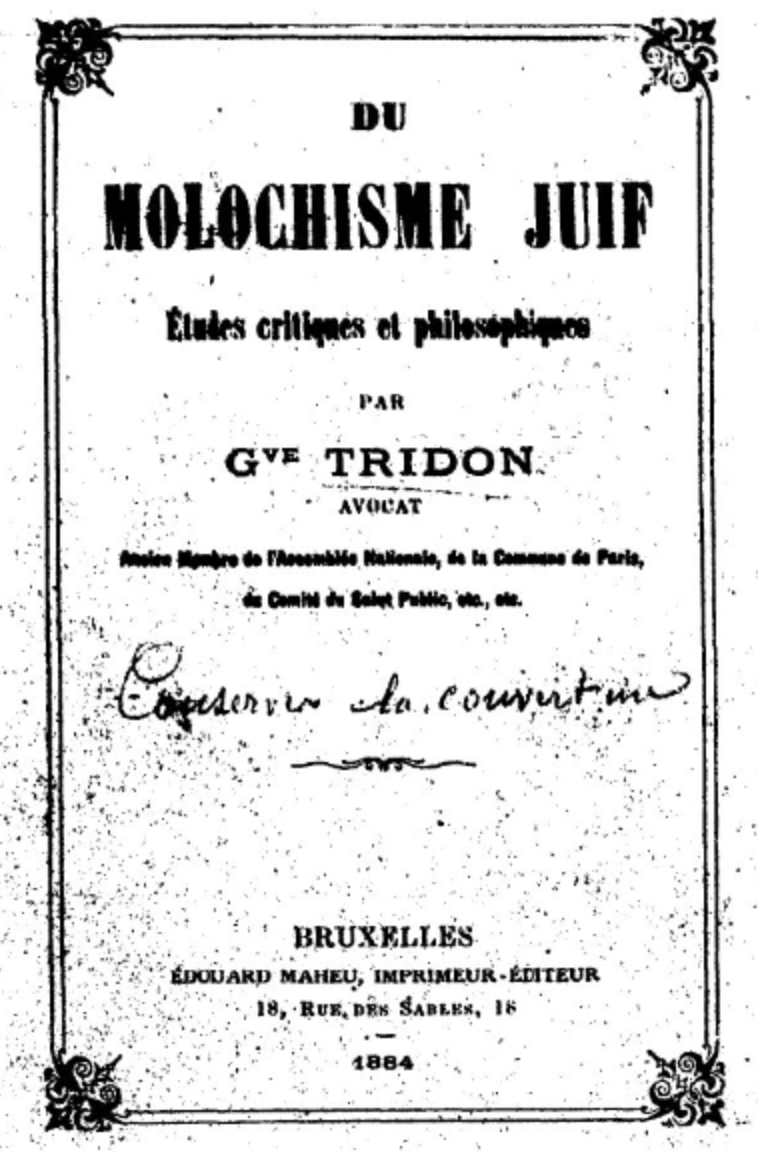

Image: Cover of Du Molochisme Juif Études Critiques et Philosophiques (On Jewish Molochism: Critical and Philosophical Studies), Gustave Tridon, 1884

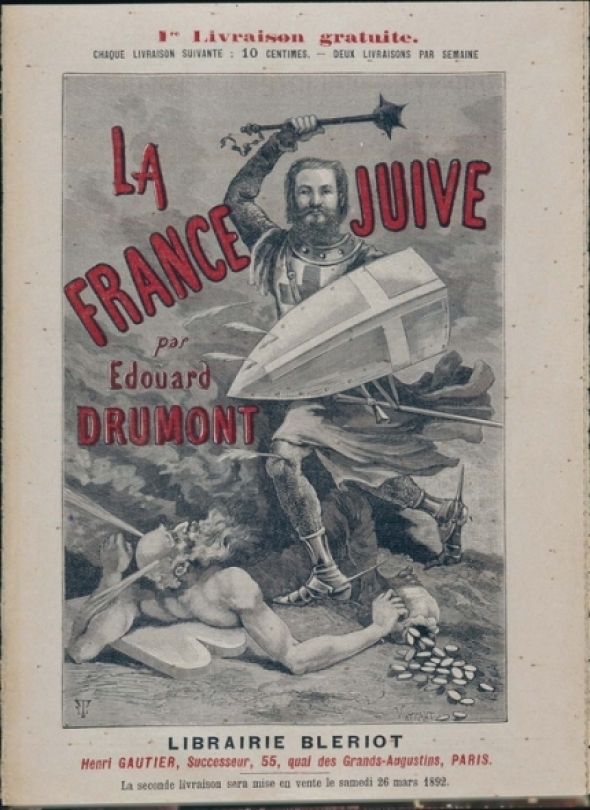

The idea of free speech that –as if incidentally, yet in fact essentially – is liable to hurt other people and is the fulfilment of a moral and historic duty was the basic fantasy, endlessly reasserted and exemplified, of the writings of Édouard Drumont. Drumont was a French writer, a virulent anti-Semite, a serial fighter of duels, the most famous of the anti-Dreyfusards and the editor of the enormously influential Parisian journal La Libre Parole (Free Speech), founded in 1892. Drumont’s many books of thousands of pages written in the 1880s and 1890s are stuffed full of horrifying anti-Semitic provocations and fantasies about besieged heroic Aryan culture that today clearly belong in the category proto-fascist. Free speech, as Drumont tirelessly defined it, not only had to be insisted on as a moral and historic, even a tragic duty, but also engaged in non-stop and unflinchingly in the face of every possible opposition, real or imaginary, no matter who might be offended. The brave acknowledgment that some oversensitive souls might be hurt swiftly became the positive demand that they really be hurt. Only when combat was really entered and the enemy actually engaged – the oversensitive soul dragged kicking and whimpering out of the dreamy narcosis of liberal civility – would the truth be able to be spoken at all. The eternal conflict of Aryan and Jew, which Drumont explains dates back to the battle of Troy and that wily Semitic rapist Paris, has brought culture to this pass, where nothing true can be said without violence. You can’t say anything any more, says Drumont, without someone getting hurt; so someone had better be hurt. The Jew, he writes, ‘has replaced violence with ruses. The fiery invasion has been overtaken by the silent, progressive, slow seeping in.’ For speech to be free again, it has to get its native violence back. Speech has no choice but to cut, punch and blast its way out of the soft-spoken language of the ruse, by violating boundaries wherever they are met. Speech is free when it refuses to be silenced or cooled, in other words when it is loudmouthed and heated, because Jewish culture, which is to blame, is silent, slow and secretive, like Freud’s death drive. The Jew, by contrast, is never violent. He naturally shirks violence and has a sickly oversensitivity to it. The Jew has taken control of France ‘not by brutal force’, says Drumont, but by ‘a sort of soft taking of possession, in an insinuating manner.’ Good Aryan feelings, he says, are ‘energetic and […] expressed in action’, like good free speech, which is never mere polite conversation but always and necessarily a heroic act. The Aryan is ‘l’être candide’, the candid being. The Aryan is also ‘the poet’, whereas ‘the Semite has no creative faculty.’ Being a poet, too, in essence means no longer having any choice but to hurt others with language, since in the current fight to the death with the enemy who doesn’t want to fight, everything but violence is anaesthesis: either you fight and give offence and be offended and find the whole theatre of provocation and conflict thrilling, flooding and energising a return to your natural state of being – or you are a Jew.

Virtually an identical fantasy was spun in the work of the revolutionary socialist writer and anti-Semite Gustave Tridon in his influential diatribe Du Molochisme Juif Études Critiques et Philosophiques (On Jewish Molochism: Critical and Philosophical Studies) published posthumously in 1884. Tridon fought for the Paris Commune and was later a member of Marx’s First International. His caricature of the Jew is more or less the same as Drumont’s, though his fearless revolutionary sadism extends to the most extreme possible poetic blasphemies against Jewish religion and also Christianity and every other religion, whereas Drumont the reactionary patriot detested blasphemy. God, says, Tridon, is a migraine. ‘Reason’, he proclaimed, is ‘the seed planted in us by truth’ and ‘the most energetic affirmation of the superiority of man and of the dignity of matter, the sensation of reality pushed right to the last consequences.’ Just as there can be no free speech without violence and hurt, so there can be no reason without the ‘most energetic affirmation’ of superiority: reason itself depends on the strict discrimination between superior and inferior. Tridon here foreshadows the derision expressed today by right-wing commentators for what used to be called ‘ ‘postmodernism’, which, like ‘snowflake’, was for a time a fashionable term of reactionary derogation with roots distantly tangled up in the history of proto-fascist anti-Semitism. Postmodernism as an insult means collapsing the natural, essential relation of superior and inferior, so that, as Ron Silliman writes somewhere, Homer Simpson is just as good as Homer. Unlike the Jew, says Tridon, who is naturally crooked and off balance, ‘the stable man lets himself be carried along in the flow of life, purifying his instincts without prohibiting them.’ The stable man, the very stable genius especially, never prohibits his instincts. His speech is the free flow of conscious total disinhibition, shot at the world like an arrow, without pity and without restraint. Only when he absolutely refuses to be socially inhibited by considerations of courtesy or by thinking of the feelings of others is the stable man free at last to purify his instincts, and thus to fulfil the destiny of instinct itself, which is also his moral and historic duty. Like Drumont, Tridon is besieged in a world in which this heroic freedom to speak freely is in grave peril. ‘I get it’, he writes, ‘to speak frankly one’s opinion on the Jewish question is to be lacking in virtue; you can have all the other Semites, tied hand and foot, but leave the Jews alone: Noli tangere, or else you’ll crash out into the mob of the prejudiced and special interest groups.’ The fantasy is always of danger, risk, catastrophe, persecution, being shut up and being prohibited. ‘Dire franchement son opinion sur la question juive’ (‘to speak frankly one’s opinion on the Jewish question’) is to speak like a Frenchman: both Tridon and Drumont insist on this essentially French character of free speech by pointing out the etymological association of franchement with the ancient Franks. Free speech is native, indigenous, thrilling, heroic, necessary, under threat, in need of violent purification, and now, today, at risk of perishing completely, under the slow, eroding waves of silent, gentle, insinuating Jewish whispers riddled with civility, careful not to give offence, and full of sickly consideration for the hyperbolic sensitivities of whatever dusty, sandy or snowy incarnation of the paralysed human flow might be listening in.

The fantasy that an elemental, even a native, freedom is under mortal threat from a culture of passive, civil, careful, considerate discourse practiced by fragile individuals who shirk violence, and that the only possible remedy at this point of extreme crisis is total disinhibition, and that this can only be, and therefore must be, violent, and that the only proof that it really is violent is when someone is actually hurt – this is the fantasy that underwrites that apparently parenthetical addition to the definition of free speech, the one that says that free speech must be free to cause offence. The stroppy insistence that you do not have a right not to be offended is really a wish actually to offend you, so that I can feel really free by being violent and enjoying the intense, shameful thrill of aggressive social disinhibition. It is a desire to be flooded with that thrilling feeling, either in fantasy or for real, essentially a desire to turn sadism fully outward, in a paroxysmic and – in fantasy – poetic assault on the face of the other who is, hatefully, more fragile than you ever will be, and therefore must know something that you don’t.

Keston Sutherland is the author of Whither Russia, The Odes to TL61P, The Stats on Infinity, Stress Position, Hot White Andy and many other poems. His Poetical Works 1999-2015 was published by Enitharmon. He has written lots of essays about poetry and about Marx, some of which are collected in his book Stupefaction (Seagull, 2011). He teaches English at the University of Sussex and lives in Brighton.

Footnotes

1 Farhad Dalal, ‘Racism: Processes of Detachment, Dehumanization, and Hatred’, The Psychoanalytic Quarterly, 2006, 75:1, pp.131-161.

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com