Crying Wolf Over Arts Funding?

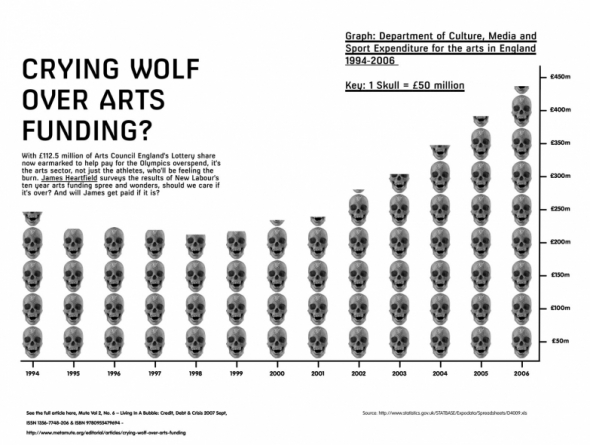

With £112.5 million of Arts Council England’s Lottery share now earmarked to help pay for the Olympics overspend, it’s the arts sector, not just the athletes, who’ll be feeling the burn. James Heartfield surveys the results of New Labour’s ten year arts funding spree and wonders, should we care if it’s over? And will James get paid if it is?

See the full skull info-graphic as PDF

Link to the full version here: http://www.metamute.org/en/files/Pages%20from%20j_hearfield_v06c.pdf

It is art versus sport according to Mark Ravenhill: ‘we’re not prepared to see such a severe curtailment of the arts to pay for the Olympics.’ He warned that public subsidy for the arts would be slashed because of the Culture Secretary’s proposal to raid the Lottery fund to pay for the shortfall in Olympic funds. Already Arts Council England – the distributor of lottery arts funding – is budgeting for cuts. Provincial theatre and other performing arts companies are crying foul.

Of course it would be a terrible thing if the arts were to be laid waste by philistine authorities, but before jumping to conclusions, we ought to get some perspective on what is happening. First, the proposal is to cap arts spending, not cut it. ACE says that once inflation is taken into account that is a cut of £30 million. Even so a cut of £30 million should be seen in context. Since 1997 the Department of Culture Media and Sport (DCMS) subsidy has more than doubled, from under £200 million to £412 million in 2006. A £30 million cut would take us back to the bad old days of 2005 – but certainly not to those of 1985 when Tory party chairman Norman Tebbit rounded on the subsidised arts as so many Trots and perverts on the rates, and Arts Council Chair Peter Palumbo wanted to sell off the national art collection to pay the Royal Opera House’s debts. Back then massed ranks of geriatric art lovers rallied to hear Simon Crine of the National Campaign for the Arts decry the Tory iconoclasts from the stage of the NFT.

In 2001 Cultural Trends editor Sara Selwood estimated the annual cultural sector subsidy at £4.7 billion (‘The UK Cultural Sector’, p.39, p.41). Since the lottery started in 1995, working class punters have made grants through the Arts Councils to the tune of £2,617,414,009, plus a further £218,350,239 to the UK Film Council and £2,152,970,098 to the Millennium Commission.

53 major new arts centres or extensions have been funded, including Luton’s £3 million National Centre for the Carnival Arts and Manchester’s £83.5 million Lowry Centre. Supply increased so fast that it outstripped demand, and many had to close for lack of interest, including Denaby’s £60 million-lottery-funded Earth centre, Sheffield’s National Centre for Popular Music, (which despite its £11 million grant is now the student union bar), and Cardiff’s £9 million Centre for the Visual Arts. In 2004 public attendance at ‘high’ cultural institutions had fallen by 20 percent in 10 years (The Guardian, 20 October, 2004).

Though subsidy to the arts is in the long run very high, that is not because the arts are unprofitable. Indeed it was the Arts Council that first drew attention to the remarkable growth of the arts sector (See Jane O’ Brien and Andy Feist, Employment in the Arts and t is art versus sport according to Mark Ravenhill: ‘we’re not prepared to see such a severe curtailment of the arts to pay for the Olympics.’ He warned that public subsidy for the arts would be slashed because of the Culture Secretary’s proposal to raid the Lottery fund to pay for the shortfall in Olympic funds. Already Arts Council England – the distributor of lottery arts funding – is budgeting for cuts. Provincial theatre and other performing arts companies are crying foul.

Of course it would be a terrible thing if the arts were to be laid waste by philistine authorities, but before jumping to conclusions, we ought to get some perspective on what is happening. First, the proposal is to cap arts spending, not cut it. ACE says that once inflation is taken into account that is a cut of £30 million. Even so a cut of £30 million should be seen in context. Since 1997 the Department of Culture Media and Sport (DCMS) subsidy has more than doubled, from under £200 million to £412 million in 2006. A £30 million cut would take us back to the bad old days of 2005 – but certainly not to those of 1985 when Tory party chairman Norman Tebbit rounded on the subsidised arts as so many Trots and perverts on the rates, and Arts Council Chair Peter Palumbo wanted to sell off the national art collection to pay the Royal Opera House’s debts. Back then massed ranks of geriatric art lovers rallied to hear Simon Crine of the National Campaign for the Arts decry the Tory iconoclasts from the stage of the NFT.

In 2001 Cultural Trends editor Sara Selwood estimated the annual cultural sector subsidy at £4.7 billion (‘The UK Cultural Sector’, p.39, p.41). Since the lottery started in 1995, working class punters have made grants through the Arts Councils to the tune of £2,617,414,009, plus a further £218,350,239 to the UK Film Council and £2,152,970,098 to the Millennium Commission.

53 major new arts centres or extensions have been funded, including Luton’s £3 million National Centre for the Carnival Arts and Manchester’s £83.5 million Lowry Centre. Supply increased so fast that it outstripped demand, and many had to close for lack of interest, including Denaby’s £60 million-lottery-funded Earth centre, Sheffield’s National Centre for Popular Music, (which despite its £11 million grant is now the student union bar), and Cardiff’s £9 million Centre for the Visual Arts. In 2004 public attendance at ‘high’ cultural institutions had fallen by 20 percent in 10 years (The Guardian, 20 October, 2004).

Though subsidy to the arts is in the long run very high, that is not because the arts are unprofitable. Indeed it was the Arts Council that first drew attention to the remarkable growth of the arts sector (See Jane O’ Brien and Andy Feist, Employment in the Arts and Cultural Industries, 1995). While investment in industry in the UK is historically low, private arts spending has continued to climb. Indeed the surplus that industry generates, that once would have been reinvested in new plants and machinery, is stoking luxury spending. Since the late 1980s the art market in London and New York has been climbing ever higher, making the careers of Keith Haring, Julian Schnabel, and Jeff Koons and then the Saatchi beneficiaries of Brit Art, Hirst, Emin and Lucas. According to the latest DCMS estimates, music and the performing arts, art and antiques, fashion and publishing are all boosting the nation’s wealth to the value of £13.67 billion (while the more business-oriented advertising and design sectors are slipping back). Certainly it is a picture confirmed by London’s leading art dealers, who record that this is still a boom time for fine arts sales.

A moot point is whether public subsidy has done any good for the arts. Whatever one thinks of Brit Art, it was primarily privately funded, blossoming in the parsimonious ’80s. How good has the art of the public sector funded 1990s and 2000s been? Anthony Gormley has reason to be pleased. But for the most part officially funded art has bent to official goals, like ‘public access’ and even building community cohesion. The one time National Theatre Director Richard Eyre protested that the government had punished excellence in the arts with ‘Zhdanovite zeal’. Any self-respecting artists would surely prefer to disturb communities and provoke the public.

No doubt there are many unfair decisions made when funds are tighter. The already festering conflict between arts administrators and practitioners is bound to surface. But experience of previous rounds of expenditure cuts suggests that a catfight with the Olympiads will only reinforce the policy of divide and rule. Certainly one hopes that as august an institution as Mute will not be axed. Still, it would be hard to make the case that the arts are hard done by in the UK.

James Heartfield is at least in part to blame for the announced cuts, having polemicised against cultural subsidies in his pamphlets Need and Desire in the Postmaterial Economy, Sheffield, 1998; Great Expectations: the creative industries in the New Economy, 2000 and the Creaticity Gap, 2005

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com