In and Out of Art and Work: On the W.A.G.E. Certificate

In 2014 W.A.G.E. (Working Artists and the Greater Economy) launched a campaign of certification which ‘publicly recognizes non-profit arts organizations [...] paying artist fees that meet a minimum payment standard’. Josefine Wikström assesses the campaign’s aims within art’s complex relation to the capitalist division of labour

Art must, in its contemporary form, be understood in two ways. It should firstly, and on the one hand, be seen as a sphere dialectically separated from life in general. This understanding of art famously emerged as a result of two parallels movement in the late 19th century: the development of capitalism on the one hand and aestheticism on the other. Through this process art came to appear in a separate – from the church and from the state – aesthetic sphere and from a standpoint of negation with regards to capitalist production. Theodor Adorno expressed this complex relation of art to capitalist production in the late 1960s: ‘The separation of the aesthetic sphere from the empirical constitutes art. […] There is no art that does not contain in itself as an element, negated, what it repulses.’1

But contemporary art must also be understood as a vast global industry, like any other within advanced capitalism, built on corporate and financialised structures of wage-labour. From this perspective it is as if art’s status as separated from life – its exceptionality perhaps – is what has made it a desirable area in which to invest. It is as if its exceptional as well as speculative status enables it, better than any other commodity, to obscure its conditions of production.

This double sidedness of contemporary art – its separateness as ‘art’ and the use of this exceptionality within an ever-increasing exploitative and speculative global industry – makes the reproductive conditions of the art industry even more mystified than in other industries. One would need an empirical Keynesian, like Thomas Piketty, to spell it all out and expose its core truth in diagrams and clear-cut statistics. In other sectors, such as IT or the garment industry for example, exploitation is taken for granted as a condition of production. Such is the contrast with regard to the working conditions within art, often covered up precisely by that: ‘art’.

Unsurprisingly this also means that the financial and labour relations within the art sector are at least as hierarchical and bad as in most other areas of production. At the level of wage structures within public as well as non-public funded galleries and museums it is comme il faut by now that the star curator and/or gallery director (often embodied by a French or Swiss white man) is paid more than all of their causal – low paid cleaning, café and invigilating (all struggling to make means meet by the end of the month) – staff put together. Tate Modern and the Whitechapel Gallery in London are only a handful of publicly funded galleries who do not pay their staff living wages.2 Within this precarious wage structure, the artist and anyone included in the exhibition of an artist, from the writer writing the catalogue text; a dancer partaking in a performance; or someone giving a talk in conversation with the artist, is paid very little if anything at all.3

For a certain critical discourse these inherent contradictions of the reproduction of contemporary art in general, and so called radical art in particular, have resulted in the internalisation and development of a questionable attitude of sophisticated cynicism towards these structures. The fact that these conditions, which are rarely worse than in other sectors but often less transparent (in comparison to a fashion brand or an IT company), need to be ‘talked’ about, debated and made into a ‘discourse’ also of course indicates the art industry’s schizophrenia. It is as if, finally addressing itself sincerely, all that museums and galleries pronounce is: ‘We are fucked so let's have a symposium about it.’ Although, of course, most of the times these symposiums assume such an abstract tone that they can’t include basic questions, such as how much the staff providing the coffee for the symposium are getting paid.4

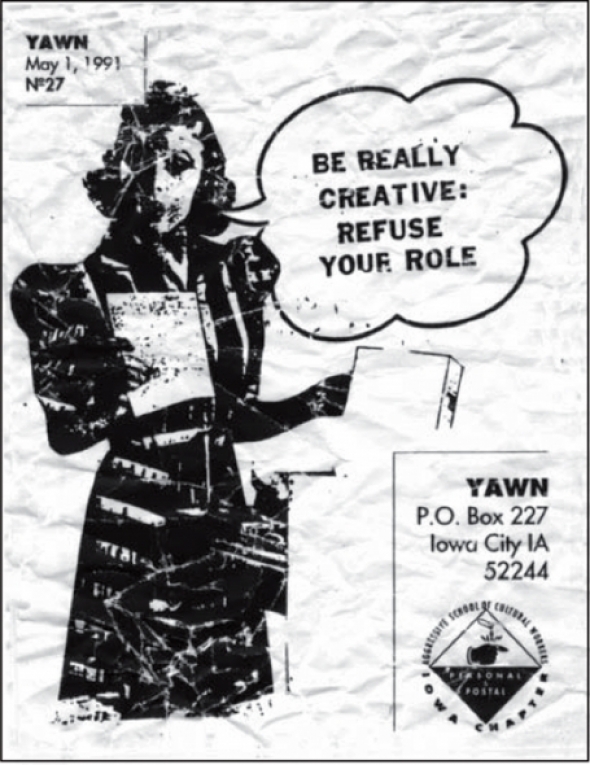

Image: W.A.G.E., Artist Payment Graphic, from W.A.G.E. graphic poster of artist survey results, 2011

Image: W.A.G.E., Artist Payment Graphic, from W.A.G.E. graphic poster of artist survey results, 2011

It is within this context that the W.A.G.E. Certificate launched in October last year and initiated by W.A.G.E: Working Artists in the Greater Economy – a New York based group of established artists, curators and writers who have been active since 2008 – must be situated.5 After having addressed the working conditions within art – and the common practice of non-payment since 2008 – the group has focused exclusively on implementing the W.A.G.E. Certificate: a document granted to not-for-profit arts organisations binding them to paying fair artists’ fees since 2011 [Ed. updated 17/03/2015]. By ‘artist’ the programme means everyone ‘who suppl[ies] content and provide[s] services in a visual arts presenting context’ – whether it be the artist herself or himself, dancers or performers, film-makers, writers or others involved in the production of an exhibition or the presentation of art. ‘Non-for-profit arts organisations’ are defined in the certificate as art institutions in the U.S who are ‘granted special status as public charities because they serve the public good.’6

W.A.G.E. Certification includes a fee schedule (or structure) with thirteen categories of commonly supplied content contributing to the presentation of art within an art context such as ‘Solo Exhibition’ ‘Artist Talk’ and ‘Performance.’ For each category there are three possible fees. Firstly, a minimum wage and secondly, a scaling up of this fee ‘using a fixed percentage of an institution’s total annual operating expense.’7 Depending on whether the latter rises above a certain amount there is also a ceiling for the fee that cannot value above the wage of a full-time staff working within the institution. All in all, the fee structure aims to be as fair as possible, making sure there are minimum fees in place but also ensuring that the artist does not earn more than others within the institution. On the W.A.G.E website there is a fee calculator that clearly shows the fees in the three categories and in relation to the major not-for-profit arts organisations in the U.S.8 Artists Space, Issue Project Room and The Artist’s Institute in New York as well as Art League Houston and FD13 in Saint Paul, MN are the organisations who have been granted the certificate so far.

Within an industry that lives off capital investments and financial structures of questionable origin and with working structures symbolised by a white European well paid patron, director or curator at the top and a low-paid precariously employed – often female – worker – not rarely from the global south – at the bottom, it is absolutely insane that artists, dancers, writers and others involved in the production, as well as gallery, cleaning and café staff, never get paid decent fees or wages. From this perspective the W.A.G.E Certificate makes transparent some of the structures in the sector of art and offers a pragmatic and hands-on system to tackle this very obvious problem. As an attack on the working conditions within the art industry it has the potential to make visible not only the unfair pay of artists but also the racialised and gendered division of labour amongst other workers within the same industry.

The launch of the certificate does however also open up all sorts of questions. Is this a demand for wages for artistic labour? If so, what does it mean to demand that art become ‘work’ and what are its contradictions and problems? Secondly, if this is not a demand in a classic sense for a wage, why demand artist fees and not work for an increase in wages and better living conditions across the board within art or even ‘life’ in general? Why highlight the labour of artists specifically within an industry in which the majority of workers, such as cleaning and other maintenance staff, have as bad, or worse, working conditions as the artists?

If the W.A.G.E. Certification programme is seen as a demand for artistic labour to be valued within the same parameters as other forms of productive labour, this must first of all be looked upon in relation to the category of ‘art’ understood as a separate sphere and as reproducing itself negatively in relation to the production of capital.

Since the wage has structured the capitalist mode of production historically – and still does on a global scale – it would, within this trajectory, be contradictory to demand a wage, since this would imply an inclusion of art into the homogenised structures of productive labour. It would, in other words, mean to continue the dissolution between art and non-art that much self-proclaimed contemporary art has already embarked upon.

The historical and contemporary reproductive conditions for ‘art’ and its relation to capital might, on the other hand, be completely irrelevant to discuss here because of a number of points. Firstly, W.A.G.E. Certificate does not ask for a wage in classical terms: a means for the worker to reproduce him- or herself in order to turn up at work day after day. As most vitally described by Karl Marx in a section where the worker speaks to capital:

But by means of the price you pay for it everyday, I must be able to reproduce it every day, thus allowing myself to reproduce it again. Apart from natural deterioration through age etc., I must be able to work tomorrow with the same normal strength, health and freshness as today.9

In distinction from a wage, the ‘artist fee’ is a regulated one-off payment that does not include preparatory work or in any way attempt to cover the basic conditions of living. This means that even if the certificate was implemented by museums and galleries those being able to make art would still be a very limited privileged class of citizens. Since the W.A.G.E. Certificate does not demand value for the amount of labour put in, it does not align with the worker who in the same passage of Capital demands of capital: ‘What seems to throb there is my own heartbeat. I demand a normal working day because, like every other seller, I demand the value of my commodity.10

Secondly, the W.A.G.E. Certificate is not a demand but a policy making programme that attempts to achieve changes in attitudes and praxis through discourse. In this sense the programme does not – and does not intend to – interrupt anything: neither art’s autonomy nor the logical conditions of capital.

Rather than a quasi-critical comment on art and its status as productive or non-productive labour W.A.G.E. however must then be seen as a genuine attempt to improve the working conditions within the art sector through awareness raising or struggle. It at least attempts to work towards conditions in which not only the richest of the middle class kids can make art. In relation to the tripling of university fees in the UK in 2010 as well as the housing market conditions on the verge of collapse this assumes an even greater importance.11 A crucial aspect of the programme is also that it is specifically directed towards publicly funded institutions. Despite the disillusionment one might bear, in times of the neoliberal state, towards the idea of a public good, the state still collects taxes – which in some sense means that the same tax payers own these institutions and thus are entitled to make collective demands upon them. In this sense, W.A.G.E. could perhaps best be understood as a struggle over revenue and the way money is distributed through the welfare state. Recent strike actions undertaken by staff at the National Gallery in London against the privatisation and outsourcing of services is another example of a struggle over the expenditure of public money and over the conditions for workers within the gallery sector. It is, however, also important to remember that these actions can only take place because the current staff are on contracts and are part of the Public and Commercial Services Union (PCS). These types of actions are difficult, or even impossible, for workers employed on precarious zero hour contracts, as is the case in most other public art institutions in London.12

Image: Seth Sieglaub, 'The Artist’s Reserved Rights Transfer And Sale Agreement', 1971

In addition approaches such as those of W.A.G.E., whose focus is on the conditions of production and exhibiting art, are important in a time when there seems to be a never ending increasing valorisation and demand from curators and art institutions alike for so called ‘socially engaged art.’ Instead of engaging with the conditions of production in the sphere in which they present and produce their work, the latter are often trying to improve others’ living and working conditions through their ‘ethical’ art. As such these projects mirror the activities of charities and art institutions who are increasingly financed with voluntary donations and sponsorship rather than publicly funded money. Rather than focusing on making art more ‘ethical’, attempts like W.A.G.E. rightly focus on the conditions of production of art itself rather than attempting to help marginalised social groups in society with their art.

However, in relation to art’s inherent contradictory character, I wonder if more radical demands could be made if artists addressed them to their other functions or roles in life: as tenants, patients, women, wage labourers and/or students? Or, at least putting as much emphasis on these types of demands as those within the art sector. If the structures within the art sector are at least as bad as within other sectors – which they clearly are, yet obfuscated by the ‘art’ as well as the neurosis of constant self-reflection – why highlight art as a particular structure? More importantly, why highlight artistic labour as a specific form of work rather than addressing the working conditions for all workers within that industry including cleaning and other maintenance staff for example? And why not simply address universal conditions through a basic income or strongly regulated housing market? The fact that a number of institutions have signed up for the W.A.G.E. Certificate demonstrates a real positive change amongst publicly funded art institutions in the U.S. and will improve the life conditions of the many artists working for these institutions. In the long run these issues need to be addressed more broadly and include all workers of these institutions. Separating artistic labour as a specific form of work within these institutions not only divides workers. Using the exceptionality of artistic labour as a specific form of production also runs the risk of turning artistic work into any other type of work and thus turning art into any other commodity. Focusing on improving the general living conditions would at least make artists and others working in that industry less dependent on it. With the risk of perpetuating a ‘modernist hangover’ this might also then enable art to stay in a dialectical relationship to capital rather than merely being subsumed to an ever-expanding industry living off that relationship, which in its expansion also at the same time diminishes it.13 As much as art is a double-sided coin, its two sides, as long as we live under capitalist conditions, need to be kept apart.

Josefine Wikström is a PhD Candidate at the Centre for Research in Modern European Philosophy, Kingston University. In her thesis, supervised by professor Peter Osborne, she investigates the concept of performance within contemporary art and from the standpoint of concepts of labour in Marx, Adorno and other thinkers. Josefine Wikström teaches at DOCH, Goldsmiths University and Kingston University. She also writes for Afterall, MAY Revue, Frieze, Philosophy and Photography and Performance Research Journal

Footnotes

1 Theodor Adorno, Aesthetic Theory, Continuum, 1997, pp.12-13.

2 See for example John Douglas Miller’s account of some of the struggles for better wages within some of the major art institutions in London. ‘Art Workers’, Art Monthly, Issue 355, April 2012, p.34.

3 Dancers who have worked for London galleries such as Raven Row, Hayward Gallery and Tate Modern in their various performance/dance exhibitions have on a general level been paid about £8/hour.

4 This is exemplified by the various symposia and artist talks dedicated to capitalist cultures and not rarely hosted or arranged by the director him or herself. One example of this was Tate director Chris Dercon’s conversation with Andrea Fraser – a boardmember of W.A.G.E. since 2013 [Ed. updated 17/03/2015] http://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-modern/talks-...

5 See the W.A.G.E. website: http://www.wageforwork.com/certification/1/about-c...

8 http://www.wageforwork.com/certification/2/fee-calculator Importantly the certificate points out that the fee should not be included in either ‘Basic Programming Costs’ such as ‘baseline costs associated with mounting or executing programs as articulated by the institution’s mission statement and constitute the basic services that artists can expect an institution to provide, irrespective of specific content.’ The fee should neither be included or part of the Production costs such as: ‘Fabrication of work, Specialized installation expenses above and beyond and Studio rental.’ http://www.wageforwork.com/certification/4/definit...

9 Karl Marx, Extracts from ‘The Limits of the Working Day’, Capital, A Critique of Political Economy, Volume 1, 1867, p.343. The extract is based on the manifesto of the London building workers who in 1859-1860 went on strike for demanding a rise in wages.

10 Ibid.

11 Parts of the art industry also manage to make a profit on the housing crisis. Tax-exempted trusts such as Bow Arts Trust with properties in areas such as Poplar in London is only one of many organizations offering so called affordable hosing to poor artists in run down, soon to become luxurious flats for city workers, and by so doing only perpetuates the housing crisis rather than provides an alternative. For an account of this see for example: http://www.eastlondonlines.co.uk/2014/05/the-balfron-tower-a-tale-of-gentrificiation/.

12 For an account of this see, http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-london-31565382

13 An expression I borrow from John Roberts. See John Roberts, 2000, ‘On Autonomy and the Avant-Garde’, Radical Philosophy, No.103, pp.25-28.

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com