Access and Repulsion

Stefan Szczelkun reviews All Knees and Elbows of Susceptibility and Refusal: Reading History from Below by Anthony Iles and Tom Roberts

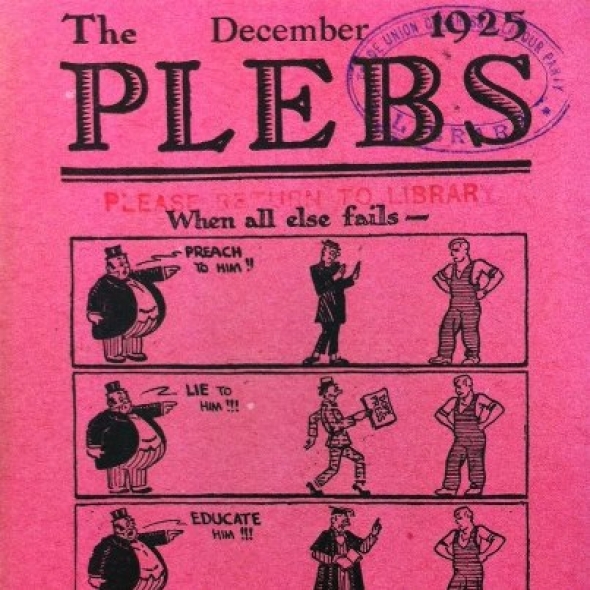

Historians from below attempted to displace conservative histories in which the struggles, experiences and agency of 'common people' were ignored.

– Anthony Iles and Tom Roberts

This book is an ambitious if idiosyncratic survey of ‘history from below’ with many juicy quotations and lively summaries. It comes together as a wonderful collection of readings woven together into a kind of macrame structure. The persistent core turns out to be the work of E.P. Thompson (1924 -1993) and especially his classic The Making of the English Working Class which was first published in 1963.i The account then explores the debates and books that orbit around, or cross this axis. It is not only the canonical books that are examined; some of the most interesting and valuable parts of the book are 'links' to obscure online articles in which people think about key problems like the latent nationalism in the work of the Thompson and the Communist Party Historians Group or the implications of historical agency.ii

The first chapter introduces a list of people associated with the Communist Party Historians Group which was formed in 1946, with E.P. Thompson, Christopher Hill, Eric Hobsbawm and others. Some of the CPHG do not however feature in the subsequent argument, while others of a similar generation do: C.L.R. James (1901 - 1989) and Selma James (b.1930) are introduced. The chapter goes on to a younger generation of key historians of the 'below' including: Jacques Rancière (b.1940), Peter Linebaugh(b.1943) and Marcus Rediker (b.1951). Others who feature prominently in the book like Silvia Federici (b.1942), Raphael Samuel (1943 - 1996), Shiela Rowbotham (b.1943) and Carolyn Steedman (b.1947) have to manage without an introduction. As the book bustles along its main thread on the work of E.P. Thompson is counterpointed and extended by the younger generation, in particular the American Peter Linebaugh and the French Jacques Rancière.

The next chapters go on to show how the white, male, elite, Eurocentric, univocal and even nationalist CPHG stereotypes of ‘the common people’ were challenged by the work of C.L.R. James and a younger generation of historians.

I was most interested in the chapter on autodidacts, a term that means self-taught but to my mind also means people who write but did not come from a literary culture or have a literary education. "Black people, the evidence suggests, had to represent themselves as 'speaking subjects' before they could even begin to destroy their status as objects, as commodities." (Henry Louis Gates, Jr) p.140. The radical autodidact did not revere the book but thought of it as something that needed 'answering back'. In my experience working class children are constantly told not to "answer back". The book does have a somewhat reductive understanding of oral culture as something that is ‘a means of getting around illiteracy' (p.142) rather than being the ground within which the ivory towers and enclaves of the literary exist. It was good to read the discussion on the pre-Victorian working class revolutionaries Thomas Spence and Robert Wedderburn, both of whom I'd been meaning to find more about for a decade or more.iii

There is then a chapter that considers 'authenticity and ambiguity' as the main problems of reconstructing history from limited traces. This is interesting but a relation to debates on the influence of literary culture on the veracity of historical and anthropological knowledge is missing here. A key reference point here has been Hayden White’s work, starting with his Interpretation in History, which came out in 1973.

The book’s narrative then goes into the nature of the university as a container of history makers. Starting with Ruskin College and later going on to the neoliberal pressures on Warwick University. This is followed by a consideration of how ideologues of both right and left have recently exploited a reductive version of history from below to their own ends. These chapters make interesting reading but in my view are minor aspects of the more profound, but difficult to quantify, influence of history from below. These influences can be of a broad but seemingly mild nature. My own step-dad Ron Colnbrook is currently nervously waiting for 100 copies of his self-published auto-biography to come back from the printer. He was in Bomber Command at the end of WW2 and then worked for BOAC before retiring and being active in the local tennis club and RC church. It is not a history of struggle that fits any left wing agenda and yet it does contribute to the image of an 'ordinary' working class life as worth writing a book about.iv Along with the growth of self-researched family history these things seem to attest to a widespread increase in working class people’s sense of self-worth. I would think that the efforts of E.P. Thompson and the left historians must have contributed to this.

The final chapter 'Unhistorical Shit' thinks about the ways that these historians shook up the field of history and changed thinking about the past, not least on the Marxist left. By the 1970s the historians from below were "largely in agreement, emphasizing the qualities of class antagonism, leaderless resistance, plurality and radical egalitarianism at work in the period leading up to and after the English Revolution" (p.278). As I write I'm following online postings on the uprising in Turkey and all these factors seem present.

Does all this suggest that these historians discovered some universal dynamics of movements from below? Or that their interpretation of such things was influential to the point of being globally distributed?

This review is a reading of a reading of the discourses of history ‘from below’ by someone who is a subject of that history, who is from the ‘below’. The canonical texts of history ‘from below’ have been written from 'above'. As a person 'from below' whose family on both sides had been displaced by war and the forces of aspiration I had a tenuous abstracted grasp of the historical construction of my position and sensibilities. ‘From below’ meant without any written history of either of my families or wider class. The sense of the past I got growing up was via an oral culture that had almost been stripped of continuity of form and content. So I relate to the elbows and knees of this books title. Evidences of my cultural background were often received indirectly or from gaps in the new suburban space my mum and dad had moved into. I knew my grandpa Sid had been a Nottingham miner until the 1926 strike and had then sold allotment-grown potatoes to survive before starting a green grocery business from a lorry. My granny Daisy had been a house servant. On my dad's side his father, who died a year after I was born in London, was a railway signalman near Vilna who had once seen Stalin pass. My dad did not speak Polish to me.

I was protective of the non-verbal sense of myself. It gave me an interesting fresh response to the world around me, which included a strong sense of class alienation which wasn't changed by going to higher education. I was resistant to professionalization and career choices. When people recommended E.P. Thompson's The Making of the English Working Class to me I was pleased to hear it existed; but I somehow didn't want to read it. I needed to reify my own sense of self through making art before I was told what to think about who I was. This is echoed in a reference to the 'celerity of thought' that is required by those without stable circumstances. p.41

So I had a defensive relationship to literary knowledge. It seemed like knowledge ‘from above’ threatened to obscure the delicate traces of my own connections to the commons. So it was interesting that this book told me that one of the gaps in E.P. Thompson's classic tome was an account of mining and railway workers. So I probably felt my history was excluded when I looked through the pages. Anyway; I didn’t read the book! History from below was also history from ‘the great and good’ and I was wary of it until I was about 40 years old. Then I made my own trail of self-discovery as to what it meant to be a working class artist. It was only as I was putting my sensibility into words on my own terms that I started to read E.P. Thompson – first taking issue with his silence on William Morris's classism and then a more positive take on his late 1991classic ‘Customs in Common’.v

Another eminent voice in this group I didn’t read is Eric Hobsbawm (1917-2012). When I learn here that he was an establishment Communist who hung onto his support for Stalin after 1956, I can see why I might have had an 'allergic' reaction. Class repulsion can work both ways. It was not just a matter of being intuitively repelled – it’s also a matter of access. Some of these books I have never seen or been aware of, let alone been able to afford. Now I want to know more about his concept of the ‘social bandit’.

So this rather long-winded digression is to show that this review of a set of readings of history from below by two non-historians is written by a subject of those histories who is also not a historian. One reason I found it a fascinating read was because I came to understand my own uneven and often difficult relation to these texts. The book is itself a personal account of two readers and their conversations rather than an attempt to make a canonical survey of what is a vast and untidy set of fields.

My own approach to working class history has been mixed with anthropology, historiography, musicology, sociology, cultural studies and in particular the growth of oral history, which is the field I have had most contact with. Oral history is briefly mentioned on page 127 but to me it is more important. Oral history is based on the recording of testimony from people who did not leave written records of their life and struggles. The oral history movement, which took off in the ’60s, with the arrival of the cassette tape recorder, aimed to leave archival records that could be used to make more democratic histories.vi Rob Perks, one of the early pioneers, is now a director at the British Library Sound Archive.

The History Workshop movement started in 1976 and championed feminist and labour history ‘from below’. It supported the development of “an oral history that was interested in recording the voices of the less powerful. That is the majority."vii

Historians are understandably protective of their skills and tend to ignore readings of history by non-professionals. And yet, a respect for readers of history is crucial if the work of historians is to change the world. This book gives me confidence and helps me begin to voice a critical perspective on my relation to these discourses. If we who are the subject of history from below are to answer back it should not be as individual critics. We readers need to find each other and talk more, and more loudly.

Info

Anthony Iles and Tom Roberts, All Knees and Elbows of Susceptibility and Refusal: Reading History from Below, 312pp pbk, Glasgow and London: Mute, Strickland Distribution and Transmission Gallery, 2012

Footnotes

i EP Thompson gets 11 references, beaten only by his student Peter Linebaugh with 12

ii The articles are by Dave Renton and Peter Hallward.

iii Thomas Spence (1750 -1814) and Robert Wedderburn (1762 – 1835). Neither of these is mentioned in Ben Wilson’s ‘The Making of Victorian Values: decency and dissent in Britain 1789 – 1837’, Penguin, 2007. We have to ask how can he write a book on this period with dissent in the title and ignore these two?

iv Ron’s book is called ‘Thursday’s Child: the personal memoirs of Ron Colnbrook’ 182pp pbk 42 illustrations, £8.99 colnbrookronald[AT]h*tmail.com

v http://www.stefan-szczelkun.org.uk/taste/CGTindex....

vi Of course it is not just oral history that can be used to understand the lives of those who do not keep extensive written accounts: archival sources such as family photograph albums and ‘home’ movies also provide sources of information from a more recent past.

Jo Spence and Patricia Holland eds. ‘Family Snaps: the meaning of domestic photography’ Virago 1991

Karen I. Ishizuka and Patricia Zimmermann, eds. ‘Mining the Home Movie: Excavations in Histories and Memories’ Univ of California Press 2007

Stefan Szczelkun. 'The Value of Home Movies', Oral History Society Journal, Autumn 2000 (V28 No 2 pp94/98)

"The films shown were mostly from the later 'democratic' period of 8mm filmmaking and included a few movies of families and holidays but also more diverse material. Home Truths was the seventh annual showing of home movies at the Museum of the Moving Image on London's South Bank. Stephen Herbert selected the programme from the archives of a network of amateur filmmakers and their descendants. He had decided to mainly show work made before 1975. The 8mm and Super 8 films shown at MOMI depicted important aspects of working class life and culture during this period."

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com