Drop the Act! A GP’s View of NHS Privatisation

How has the ConDem’s de facto privatisation of the NHS in March 2012 played out in the doctors’ surgeries, hospital pathology labs and boardroom shenanigans of the UK? What do the promises of ‘patient choice’ and GP commissioning really amount to? Can ‘choice’ be turned into a weapon for those resisting the sell-off of the health service? Mute talked to an inner city London GP

GP: I am a GP in London working in a Clinical Commissioning Group [CCG] which is going through the authorisation process towards becoming a statutory body. I have been a doctor for about 18 years.

Mute: So, 18 years – how many reforms is that?

GP: There's one about every five years. Basically, with every government there's a reform, and also in between. For example, NHS foundation hospitals, day to to procedure changes and alerts, of course with each reform there is a change of staff. Then there are huge things like NHS direct which was set up in 1998.

M: Why is NHS Direct being replaced by the 111 service?

GP: My opinion is that the new 111 is all about the government's choice rhetoric and agenda. It’s a free phone call which theoretically puts you straight through to your GP, which is very appealing to people. This has been top-sliced off the NHS. Each 111 phone call costs the NHS £8. But it isn't beneficial to access in terms of good care. What you really want for an intelligent prioritisation of someone's health concerns is for them to be speaking to someone clinical who can triage their call, and put their needs into the system in order to be dealt with most efficiently. 111 is presented as ‘you'll phone up, you'll get access, easy’, but it’s never easy. This service is open to competition under the new Health and Social Care Act, so any phone company can bid to run this service. But there are lots of problems with the new 111 system. For example, if the call is made during surgery hours and it is possible for your own doctor to answer your call, from a place where your medical notes are held, wouldn't this be better? Is it fair to jump the queue, and get in front of someone who hasn't dialed 111? How would it link in to out-of hours services? It's a bit of a mess.

M: How does all this play into the politicking around waiting times? Hasn’t the speed and turnaround times within the NHS become a political hot potato?

GP: My opinion is that what the government thinks everyone wants to hear is, ‘you won't need to wait, you can get into wherever you want, whenever you want’, so that mind-set forms the basis of their rhetoric. But in my opinion, that isn't what people want to hear. It is true that younger people want instant access, they're busy, but older people or sick people want and need more continuity of care.

M: I suppose the younger generation are less likely to have chronic conditions that need continuity of care, they just want their prescription and off they go...

GP: There is truth in that, but what’s happened possibly is that we've forgotten that the NHS is a precious resource that we all pay into, and that we all need to share, and think about, and use carefully. We've begun to think of it as a bit of a ‘right’. It needs to match our needs precisely, and when it doesn't we're not happy. In as much as this Act appeals to anyone (and I'm not sure it does), it has maybe appealed to this side of human nature.

M: Do you think that the reforms key into the wider debate around benefits in which the notion of a general abuse of the system is used to withdraw universality of service?

GP: In January 2010, the government manifesto said:

We will free NHS staff from micromanagement

Increase democratic accountability

Give patients the power to choose treatments that are best for them

We will cut the cost of administration by £5 billion (this is ridiculous, admin costs have soared, especially if you include redundancies etc.)

Every patient will have the power to choose any health-care provider: independent, voluntary or community.

We will stop the top-down reconfiguration of the NHS.

Every single one of those commitments has been turned on its head.

In June 2010, the Commonwealth Fund reported that NHS was second from top (just below the Netherlands) on parameters of quality, efficiency, access to care, equity and healthy living. That's how well we were doing. And that was widely publicised, and was a very substantial report. There is a huge amount of work that shows that a public health system is by far and away the best model, and ours is one of the very best.

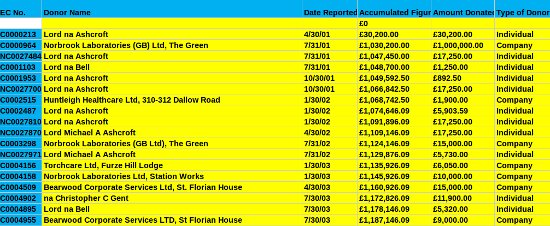

Image: Sample from the long list of Tory private health care donors

M: And the road that this Act is swiftly taking us down leads away from that system and towards the US model, which the same studies and reports show to be one of the worst performing in terms of value for money, outcomes, morbidity rates, expenditure per capita and universality. So this begs the question: for whose benefit are these reforms being forced through? And how was this Bill sold to the public, or was it was pushed through without a mandate?

GP: I certainly don't think it was sold to the public. In January 2010 the manifesto was published and in March 2012 the Bill was passed. It took just over two years and two months. Now, it took about this much time for GPs to understand what was happening themselves. There was NO time to educate the public. Efforts were made. Everyone (in the NHS) was so busy, first of all fighting, arguing, working out the nuts and bolts. Some GPs were for it, but the majority were against it, by all accounts. The British Medical Association (BMA) didn't oppose the Bill very forcefully while it was being read

M: But we now have a new head of the BMA, Mark Porter, who seems much more actively opposed to the Act. In an article today, he is very dismissive of the patient choice agenda, which he describes as a red herring exercise. Or you could say a Trojan Horse in which to conceal the true nature of the reform – privatisation – and drive it into the heart of the NHS.

GP: Yes, patient choice is a complete red herring. But in some ways, it’s all a bit late: the Bill is passed. My point is that many many people have said most doctors are against it, and I’m sure that's true, but there was no time to meet, talk together about it, and the first effect of the paper's publication was ‘divide and rule’. Everyone was in chaos. We will never know, but there would have been people in the NHS who would benefit and so be pro-reform. But this was a minority.

One thing that kept me awake all night worrying about the Act, and others too – we all spent sleepless nights, and still do – was the idea that the government just wants to unburden itself of the massive NHS budget. No Secretary for Health wants such a huge responsibility. So there was a point where I figured that all governments would think the same. But to do this without a mandate to something that everyone in the country has been paying in to, which we all think of as ours... It was discussed whether it was actually legal.

M: Of course, there's the opposing view that it would be illegal not to do it, which is one of the reasons the bill came through. In terms of the WTO 1995 General Agreement on Trade in Services treaty, which we all seemed to have signed so momentously (without a mandate either), countries have committed themselves to opening up public services, and this links to competition law... The sleight of hand happened really when health care became a commodity, like everything else that can be traded, and was at that point no longer exempt from competition law.

In our previous discussion, there was an emphasis laid on the fact that it was going to be the GPs, with their professional expertise and local knowledge, who would have control of the NHS purse-strings. On the face of it, not such a bad idea. Is it still the case that GPs control Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) and thus expenditure?

GP: Yes, in theory, after all,who else is best positioned to commission? There is no doubt that the right GP in the right CCG is the best person to commission. But there are several other sides. One is that, they cut the cost of implementing the CCG system by about 1/3 That’s the first thing. It automatically means that you'll have many GPS suddenly in managerial roles. This is not a bad thing in and of itself, but it means less clinical time for practice or teaching and so on. And it increases the emphasis that a GP must place on cost per patient treatment.

GPs have always borne cost in mind up to a certain point. For example, by containing treatment within primary care, that being less costly than hospital visits, by managing things better and co-ordinating out-of-hospital services better. But, now cost might conflict with clinical management. My understanding is that most GPs don't disagree with clinical commissioning as such, but, they do feel that it's a bit of a set-up.

Overall, if a CCG has worked with their practices for a long time and if they had prepared for the Bill, these issues are less incumbent. But if the Bill had been forced on an unprepared CCG then they may very well be in the position that their member practices are not engaged and their leadership is not democratic and transparent.

M: One trick to get potentially controversial or right-leaning policy past the public is to dress it up in the guise of democratic localism. For example, with the Localism Act itself. The public were told they'd been given more local control regarding planning decisions. What has really happened is that the official criteria for the evaluation of planning applications in terms of what constitutes the ‘public good’ or local benefit have been altered to prioritise economic interests above all others. The interests of business have been inscribed into planning laws while communities have only been ‘empowered’ to commission new developments not prevent unwanted ones.1 This seems to be the trick that this government is pulling with the NHS too. They're using the rhetoric of local empowerment, and trading on GPs’ trusted reputations built up through long years of hard work, to force through the carve-up of the NHS.

GP: We felt we were being set up to fail. Then what started to happen was that the number of services we could commission started to decrease, and so did our budget.

M: So who is now in charge of most of the £60bn NHS budget, if the GPs’ proportion of budget has shrunk?

GP: Well, directly above CCGs is an autonomous Commissioning Board. ‘To support GP consortia in their commissioning decisions, we will create a statutory NHS CB. This will be a lean and expert organisation, free from political and day-to-day interference.’2

M: So they're basically absolving themselves of any responsibility.

GP: But that board is still very much in disarray. In fact it doesn't actually exist yet, despite the fact that we're all going through authorisation as CCGs!

M: It’s very clever the way in which the government has basically almost done away with a whole government department and the responsibility for the public health, without any mandate, and called it ‘freeing us from political interference’!

GP: Yes, isn't it amazing. Although the government is absolving itself of responsibility on the one hand, it is still free to exercise a veto over the CCGs – so it’s both diffusing responsibility for day to day decision making, and in a way that’s possibly less accountable than in the days of PCTs, able to abolish CCGs if decisions don’t go the government’s way, i.e. in favour of private sector providers.

M: And the government will have redirected all the anger which will ensue from the cuts - from government to the front line workers.

GP: This is what I feel it's very important to inform the public about.

M: Kailash Chand (deputy head of the BMA) today lists his concerns about the process by which CCGs are established: ‘Many GPs are concerned that they could become administrators of NHS cuts’, i.e., they'll get the blame, basically, for all the rationing, the budget cuts, and so on. Another concern is that, ‘The NHS Act also enables CCGs to enter into joint ventures with private companies to outsource most of their commissioning work to private companies with vested interests beyond the scope of full public scrutiny.’

Who are these third parties who will have potential control of NHS budgets? Would they be able to hide from public scrutiny using the commercial confidentiality clause? Who will make sure that vested interests are not abused? Who will pay the legal and investigative bills for doing this? Who monitors Monitor? Who appoints monitor board members?

More of Kailash Chand's concerns are that some GPs are reporting that ‘practices are being pressured into signing these new constitutions without enough time to check how their practice and patients will be affected’, and that ‘participation rates among GPs in many CCGs is actually quite low.’ So, the idea of GPs being in the driver's seat is not actually, in practice, being fulfilled.

GP: To set up this constitution, as well as going through authorisation, as well as doing your job as a GP, as well as keeping up with medical training and now revalidation, as well as having families... I can completely understand why this rate is low.

M: Would that almost have been the expectation then, that GPs would very quickly sign off the responsibility for commissioning to a third party?

GP: My suspicion about these reforms is that they were hurried through for a reason. That was the only way to get them through.

M: Mark Porter emphasised today that it is important that GPs feel that a CCG is accountable to them, not the other way round.

GP: Yes, but in practise, that's a great deal of work. To engage with a CCG on that minute level to get it running really well, takes a very long time. The CCGs which have done that, started the collaborative process early and took it seriously, and have preempted the Bill by starting this process; they’ve done a very good job.

M: Why did those GP consortia embrace commissioning early?

GP: They didn't embrace commissioning. It was more a case of pooling resources, collaborating, and educating each other. These are all things which will suffer as a result of the Bill. The Bill wasn't necessary for these improvements to happen; they were already happening. This Bill will put competition in place of all that. You don't need to destroy the NHS to get GPs to collaborate.

Image: Danny Boyle's Olympics Ceremony tribute to the NHS on the heels of its privatisation

M: Looking at Serco’s attempts to corner the market in pathology labs, the dates indicate an intention to get in early. They took over the labs at King’s College and St. Thomas’ Hospital in 2009 – a deal apparently worth £800m over the next decade.3 (A 2006 study commissioned by the Labour government seemed to indicate that standalone labs run independently from hospitals would provide the best value for money.)

GP: That's exactly what you don't want. You don't want some huge, outsourced, national lab. What you want are small, local services which work closely with your teams, and with whom you can decide how you're going to communicate. It happens all the time, where lab results aren't quite clear, and a bit of double-checking is needed: a quick phone call to someone whose name you know, with whom you can communicate back and forth quickly and so on. A huge, inflexible corporation with labyrinthine departments with whom communication is difficult and with whom interaction is difficult is not what you want.

M: It sounds like you have a very good relationship with your present path lab.

GP: It's very, very important to work closely with the laboratory that you're sending samples to. Many times, I ring up and say, ‘Not quite sure about this result...’, I'll speak to a consultant, put the phone down, and get on with my work. That won't happen with Serco.

M: Well, it's already not happening. This has come out under a Freedom of Information request. There have been very serious cases of results being lost or delayed, mistakes being made, and so on. Miscommunication has already been happening.

GP: Another way that the Act is disastrous is in education and training. Fragmentation and competition will not engender learning. Education might be more important than cost when it comes to outcomes. We all work with evidence-based medicine. We must all keep up to date with medical developments. The Bill's fragmented this. They originally tried to do away with NICE, an independent organisation which weighs evidence impartially. The ABPI (big pharma) now have a really heavy weighting in NICE.

M: So the pharmaceutical industry is marching straight in, even to the monitoring organisations, in order to guarantee a large slice of the profit action inherent in this legislation? What kind of watchdog bodies are in place with the new system?

GP: Well, now we're getting on to things which we don't really understand. When I say, we I mean nobody gets it. Section 4.27 of the Bill states: ‘Monitor will be turned into the economic regulator for the sectors with 3 key functions: it will promote competition, support price regulation and ensure access to key services.'

M: So it’s there to make sure that private health companies get a look in? I’ve heard that Healthwatch's legal status has been reduced recently. Is that true?

GP: I’m still trying to get my head around that. LINKS is being replaced by Healthwatch; this should be a representative organisation that is accountable to patient members, but Healthwatch will be farmed out to private organisations and I’m not clear how it will work in the future

M: So, the competition rule ushers in huge potential for corruption, vested interests, increased costs, fragmentation, lack of new training, all the things that aren't in the best health interests of the patients or the taxpayers, which interests the NHS had served so well until now?

GP: Thats the fear.

M: For example, the BMI Meriden Hospital in Coventry, which was given scope to admit private patients and then immediately began ordering staff to make NHS patients wait longer than was necessary, in hopes that they would take their profitable private option.4 How will we keep a lid on all of that, once that monster's let out of the bag?

M: You mentioned earlier that you saw some potential leverage for members of the public wanting to prevent some of the worst aspects of the Act?

GP: I think it's around turning the government’s choice agenda on its head. I think it’s important that we encourage CCGs to use patients voices to help it shape policy and opinion. It’s too late to put this into CCGs’ constitutions now but patient voices, channeled via patient participation groups or other interested parties can help. It’s time to learn about your CCG. But just to give you an idea of what we’re up against, we’re actually heading towards personal health budgets. That’s how bad it’s going to get.

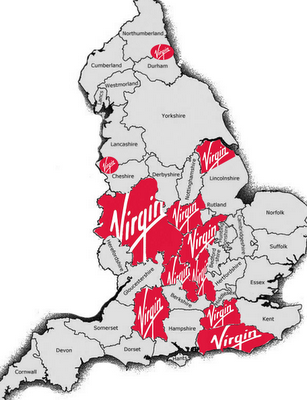

Image: Areas where Virgin now has control of parts of our health service

M: Which, again, is triumphantly proclaimed as being a choice initiative: you can spend your health budget how you like! Never mind that you know nothing about medicine. Which is where the rhetoric about choice and patient-as-consumer falls down: there's a basic asymmetry of information, which you don't have when you're buying a pair of shoes.

GP: Exactly. Sharing information properly takes a long time, which GPs are already short of, as we all know. NHS budgets are being diverted according to age, too. This has the effect of transferring it to the shires, where the greatest proportion of elderly people live. Inner city areas where health outcomes already are poor because of poverty, where disabled people's benefits are being slashed, where people are being forced into poverty because of austerity and high unemployment, will have less of the health budget to deal with the consequent decline of health. Putting a personal health budget responsibility on the patient absolves the state of the responsibility for the nation's health, but will be extremely difficult for anyone to get right. What if you're a child with a long-term illness? Where will people get their drugs information from? Even GPs aren't expert enough to see through the gloss. What chance has a layperson to get his or her PHB right?

M: Are these plans actually being discussed?

GP: Worse, personal health budgets are being piloted at the moment. They might even be rolled out at the beginning of next year.

M: And presumably, top-ups are optional after that? That’s the road to an insurance-based system.

GP: And it's a crazy idea because what works so well with the NHS is that the cost of having a healthy population is shared equally between everyone, so no one person ends up destitute from being unlucky enough to have a chronic condition, or indeed from just getting old!

We hear terrifying statistics on the number of old people dying in massive debt because they've paid for end-of-life care and have had to go into debt to keep up the payments because they're just not dying quickly enough!

So, the Patient Participation Programme, which is all part of the choice agenda, could be used to make sure that the competition elements of the Act are kept out at a local level. Patient Participation and Engagement is a way of influencing your CCG, and getting educated about your local service. And it’s also important to ask who is providing your services? Because from now on, anyone could be providing health, and using the NHS logo.

M: Which is of course a trusted and therefore valuable brand.

GP: If you really want to keep the NHS alive, as a patient you can choose NHS over ‘Any Qualified Provider’ (AQP) if this is possible.

M: How do you do that?

GP: By staying as informed as you can, also. I'd fund Keep Our NHS Public, that's very worthwhile. Join your local branch and talk about it on the street, follow blogs. Twitter seems to be a good source of information. 38 degrees are trying to stop privatisation, but the most important thing, for groups to be doing is to challenge the cuts. The Labour government have promised to repeal the Act if they win the next election, but whether that's possible remains to be seen. But there are a lot of people who just aren't that interested, especially outside of inner cities.

M: I think the idea that healthcare is still ‘free at the point of use’ creates a false sense of reassurance.

GP: The road we're being taken down so quickly is yet to be perceived by most people. The realities of the future are not thought about.

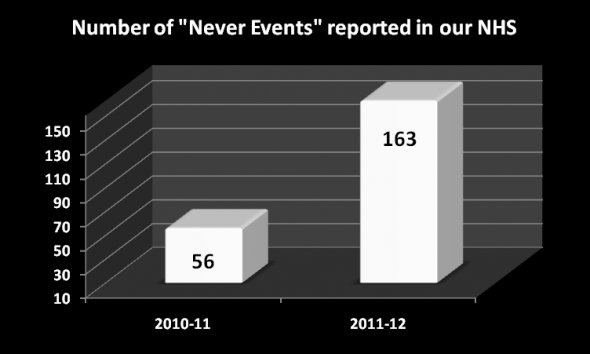

M: And also the interests behind privatisation: over £10 billion in donations to the Tory party so far from the 10 private health companies who have won the biggest contracts; massive vested interests in private healthcare throughout parliament, including the House of Lords, who finally passed the Bill which everyone was against.5

GP: Throughout the process of authoring the Bill there were conflicts of interests. Professionals who protested early on were kept out of discussions. There was a massive opposition from many professional health bodies – the BMA, Royal College of General Practitioners, Royal College of Nursing, Royal College of Ophthalmologists – which all linked up. But what happened was that Cameron said that he wouldn't engage with anyone who disagreed with the Bill. So for example the RCGP were actually kept out of negotiations!

M: That’s democracy for you.

GP: So, Clare Gerada, head of the RCGP – the organisational body being asked to take on commissioning! – was not invited to the negotiating table. She was told, no you can't come because you don't agree with the Bill. So the only people who attended the meeting were the ones not opposed to the Bill.

M: And they talk of choice, listening exercises, and so on.. Very sinister goings-on...

Footnotes

4http://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/health-and-families/health-news/private-hospital-told-doctors-to-delay-nhs-work-to-boost-profits-7962582.html

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com