50 Shades of Rape

In his latest book, Stewart Home draws the comparison between the rape of unconscious victims and capitalism. But, asks Hestia Peppe, does this insight make his parodic use of the rape-revenge genre something more than a pointless exercise in cynicism?

In an interview with Michael Roth of opsonicindex.org Stewart Home riffs on the subject of delayed publication,

Publishing really is incredibly conservative and if, like me, you understand that literature is about the creation of reactionary bourgeois subjectivities and then write with the intention of destroying the novel as we know it, what you do tends to go down badly with most editors.1

In the same interview Home describes his novel as ‘funny if you've got a black sense of humour, and hopefully it is unreadable and distressing to those who are uptight, po-faced, repressed and even more deluded than the narrator!’

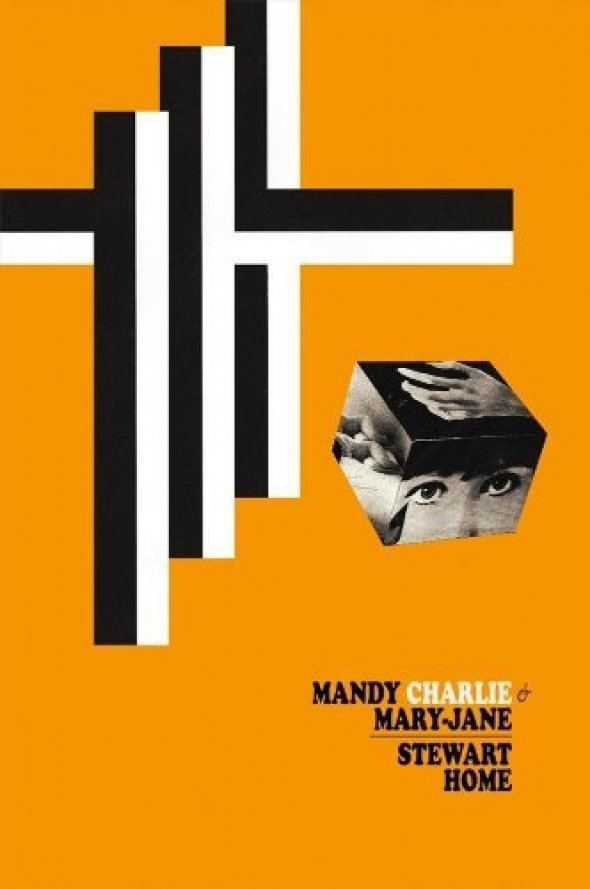

Stewart Home’s Mandy, Charlie & Mary Jane was written following the author’s experience in London at the time of the 7/7 bombings in 2005. According to Home the reflections of this experience that it contains made the book unpalatable to publishers and so, until Penny Ante Editions finally came to its rescue in 2012, it languished in the wings waiting for the world to loosen up and get hip to its edgy groove.

On his blog Home describes the book as ‘in part inspired by certain reviewers suggesting some of my earlier novels might be English equivalents of American Psycho’. Not content with a straight comparison though, he interprets this analysis of his work as a misguided attempt to place him in a ‘mainstream context’. Elaborating on the subject of ‘the mainstream’ at some length he concludes that his references to ‘Italian Eurosleaze directors’ like Lucio Fulci and Reggero Deodato prove clearly that he couldn’t possibly be considered anything other than totally cult. Mainstream writers only refer to Steven Spielberg or the music of the Rolling Stones, so you can tell.

Since Home seems to be all about radical sloppiness and puncturing the inflated egos of the artistic establishment, I’m gonna come totally clean and say that I don’t normally read a lot of contemporary male literature. It hasn’t been a conscious choice but it’s also not a bias I’ve particularly cared to address. You can’t read everything. There’s so much incredible writing by women out there in much greater danger of not being read and I constantly meet (male) people who actively avoid reading anything by a woman because ‘they can’t relate to it’. Before I was offered this for review I’d never even heard of Stewart Home, not, I might add, because he’s super obscure – turns out 30 people I follow on twitter follow him – but because, as is easy in a world filled with popular culture, I was paying attention elsewhere. Still, I’m down with books in which whole chapters are devoted to describing art exhibitions, or at least I have been before.

Mandy, Charlie & Mary Jane opens with zombie references and campus killers and I’ve been getting into my genre horror more recently and I’m all excited because right off the bat the narrator’s talking about the possibility of the rape-revenge horror form as feminist critique. I’ve been wondering about rape in narrative film since last year when I had an inadvertent run of watching movies that all revolved around rape. It seems to me that rape is usually used either to intensify the narrative or strengthen a central female character. Need to distance yourself from your cutesy twin sisters? Star in a rapey-sex-cult movie like Elizabeth Olsen. Wanna add depth to a tired game and movie franchise? Reverse engineer your leading lady (Lara Croft) so her backstory includes rape and abuse. That which does not kill us makes us stronger or something, but I do grow exceedingly tired of the fact that while we have no formal system for making sure boy children are clearly taught not to rape, one is more than likely to come across representations of the subject while eating popcorn. Actors who play men who rape are as or more often extravagantly congratulated on their bravery in descending into the minds of such ‘monsters’ as the actresses who play their victims. Writers who create characters with dark habits similarly impress us; consider the acclaim given to the creators of Patrick Bateman and Humbert Humbert (I must confess a love for Nabokov). Home references Wes Craven’s debut movie, Last House on The Left, which later on I google and discover I’ve watched half of and forgotten about. Watching it fast on the heels of the accidental swathe of rapeful movies, I decided mid-showing I had better things to do with my time. Last House is not only a narrative predicated entirely on rape and subsequent revenge, but a movie shoot about which apocryphal stories proliferate, detailing how planned scenes were kept from the lead actresses in order to ensure their authentic horror was captured for the screen. In an interview online Craven talks about what a ‘wild time’ they had shooting. The reference is totally apt. Wes Craven was working as a college lecturer before he got funded to make Last House and Stewart Home’s character Charlie Templeton, a bored professor at the City University of Newcastle on Tyne (hilarious acronym, check) can obviously relate. Charlie Templeton is Home’s narrator, presumably the mouthpiece of the aforementioned reactionary bourgeois subjectivity. I am really excited to see how, through Templeton, Home intends to ‘destroy the novel as we know it’ particularly if this can be done by interrogating the canon of horror, sleaze and rape revenge that we’ve inherited from cinema.

Image: Still from Wes Craven's The Last House on the Left, 1972

I feel like Home and I are on the same page. I am so up for a campus novel which critiques the neoliberal university via a horror/gender smashup. Bring it on! There’s a scene near the beginning of Mandy Charlie & Mary Jane involving the narrator imagining a female college lecturer happily receiving oral sex from a zombie while menstruating which I read with amusement and approval, It’s funny. Only later do I read one of the many breathless fan-boy reviews of the novel in which this scene is described as some kind of ultimate reader test that only the purest horror lover will make it through. I’d say it was the highpoint of the book, but not that it was the most horrific moment.

On reading further, it becomes clear we aren’t on the same page. I’m growing impatient with the repetition of scenes in which Templeton obsessively fucks his wife without her knowledge while she’s out of it on sleeping pills and fails to recognise it as rape (she once told him he could, but it’s doubtful that pass extended into a future where she’s actually kicked him out of the house). He does it to his mistress too although she kind of does give him permission. It feels like this scene recurs constantly, each time identical, every gesture described echoes the time before. ‘Once I’d buttered her up with my saliva’, ‘I spat onto the tips of my fingers and used the saliva to lubricate her cunt’, ‘I pushed my tongue between the lips of her cunt to lubricate the lady’. It’s as though it’s a scene in Templeton’s favourite porno that he’s rewound a hundred times to show it off to you or worse, as if fucking/raping (not much difference to him, he keeps blanking out because of all the crack anyway) is as systematised and mediocre as logging into Facebook. Perhaps this is the genius of the book – I haven’t read American Psycho, although I’m told it makes a virtue of monotony – but I would have hoped that such a self-proclaimed master of the transformative practice of plagiarism would be able to do more with the subject matter he borrows than simply appropriating it. Perhaps Home has grown giddy and disorientated after years of working with multiple ironies and can no longer distinguish between cynical appropriation and joyous piracy, opting simply for the easy option, cynicism as the path of least resistance in the face of despair. I’m increasingly hacked off and concerned that this means I’m not getting it and so begins the aforementioned and inevitable Google session. Just as I’m realising how disillusioned I am with the whole thing I discover how very popular Home is. Quite the cult hero. The stakes are raised. All those friends of mine on twitter will definitely be able to tell if I don’t get it. His Wikipedia entry tells of a consummate provocateur from the good old days of punk – a master of disguise and anti-propaganda. Home hangs out with Bill Drummond, people started a rumour that he was Belle du Jour; he’s a trickster legend, a cowboy anti-darling! By the time I’ve read the entry I’m fairly convinced he wrote it himself. I go on down the Stewart Home rabbit hole. I read his blog, I read other reviews of the book (never do that!), I read the interview with Michael Roth and I know I’m fucked. I’m the uptight chick who can’t get past use of rape as a metaphor. It’s at this point I realise Stewart Home is some kind of art world master troll figure and that, unlike feminists, trolls (whatever it is they actually are) are totally hot right now.2

I stick with it, I finish the book, no miracle of narrative resolution occurs unless you count comparing Hell to South Kensington, which I don’t, but which in yet more self congratulation on the endless blogs and online interviews Home seems to. Rape revenge is not truly critiqued but is enacted to a lacklustre extent (Templeton is only momentarily irritated when he gets his comeuppance from practically the only female of significance in the book who isn’t being used as a FleshLite, but then he doesn’t care about anything, everything’s totally pointless, rape as much as anything else I guess). There’s a lot more of the lacklustre (homage to Easton Ellis?) than there is of the ‘exploding into the stratosphere’ that Home promises online. After a month of worrying about what the hell I’m going to say about the thing and consulting the beautiful, dedicated cult movie geeks I’m super lucky enough to share a house with (how else does an uppity feminist end up watching half of Last House on the Left by mistake?) it dawns on me that my fears of missing something (way scarier a prospect than any scary movie, or any novel about scary movies) could actually just be misplaced. I think I I think it’s weak and I’m scared shitless of having to say that in public because the author himself has made it clear that anyone who doesn’t love it doesn’t get it. I’m intimidated and alienated and much as I want to be able to participate in all this nonchalance, I’m stuck writing an outsider analysis. So be it.

The metaphor at the heart of Mandy, Charlie & Mary Jane is capitalism as rape. Or as the author consistently euphemises, along with Michael Roth, the one reviewer I’ve read so far who actually mentions this supremely central device in the book – capitalism as sex with women who are unconscious. The alienation of the subject under capital is expressed in the image of a very bored man, disgusted by the possibility of fucking anyone with their own agency or consent. I’m not a rape survivor but I know enough about solidarity to know turning rape into a metaphor is bad form. I know we have not collectively established means of educating men not to rape and I know most portrayals of it are made for the purposes of entertainment. I don’t care to censor anyone and Stewart Home can write whatever he likes, but if he knows so goddamn much about horror I wish he’d actually give a sense of what’s so important about it. The book seems far more concerned with pointing out that nothing is important except of course for lists of movies that make you cool versus lists of music that doesn’t. If I’m getting it right it’s Eurosleaze – cool, Coldplay – uncool. Templeton, as a narrator is ostensibly ‘unreliable’, that is wacked out on crack and coke and a dickhead to begin with. It strikes me as entirely possible Home is actually not at all interested in the horror genre but merely using it as carefully researched window dressing for the ‘reactionary bourgeois subjectivity’ he’s been constructing in the form of Templeton. His answer to Brett Easton Ellis requires the trope. In a number of interviews online and indeed his own blog Home describes his character Charlie Templeton as ‘a complete cunt.’ There’s another problematic metaphor. We know this isn’t full-on autobiography, Templeton apparently is ‘stitched together from some of the most obnoxious academics I've come across over about 25 years’ but as his experience of the 7/7 bombings and of the various art exhibitions he visits are confirmed by Home to be based on ‘real’ life I’m tempted to include Home in that coterie. When Templeton’s ‘good’, wandering innocuously around art galleries and on the fringes of the post-bomb chaos in London, he’s Home, when he’s ‘bad’ he’s a concoction. The persona is crudely constructed, it’s not its authenticity or lack thereof that concerns me, or the ‘truth’ of the experience, but its lack of complexity and its aggressive manipulative strategies. You can see the joins, and not in a Brechtian way. Stewart Home seems to have mistaken nihilist dissociation for Brechtian alienation. I realise I’ve been had, again, into thinking that there might be genuine scholarship at work here. It seems Home’s priority is to show that if at any point as a reader one attaches significance to anything then one is as guilty of reactionary bourgeois subjectivity as, or as he puts it ‘even more deluded than the narrator!’

There may be something to be said for Home’s analysis in Mandy, Charlie & Mary Jane of the privatisation of the university system, and his admirable articulation of hostility toward Coldplay and the whole canon of globalised rock music, but I’m too busy being othered by every cult movie nerd-boy reference. My experience of reading Home’s book is, I imagine, pretty close to that of Templeton’s female students’ experience of the character’s drug-addled classes. I had a few lecturers like that myself in 2005. Written entirely in undesignated direct speech, the dialogue in the book is very difficult to attribute to specific individuals and the characters merge into two categories; those who Get It (Templeton) and those who don’t (everyone else). It’s clear the contempt Templeton has for his students, and it’s not unlikely that Home shares this too. Flashback to every moment of disappointment in discovering a subculture that to a lonely girl seemed like a haven only to realise there’s a hazing system and a secret handshake and a gender prerequisite barring the threshold. Home claims not to be part of the mainstream, and sneers at it. Maybe it’s a generational thing but giving talks at galleries and public institutions, publishing numerous books and getting reviewed in The Guardian looks pretty mainstream to me.

I actually do get a lot of the references – growing up with IMDB and spending close to ten years in house shares peopled by passionate culture heads, in which cult movies are literally part of the furniture – and they don’t shock me. In Mandy, Charlie & Mary Jane, Stewart Home has almost written the definitive journey-to-the-centre-of-the-horror-at-the-heart-of-capitalism-that-is-rape-culture but instead he just replicates the experience. He generously provides reams of references for the legions of fan-boys who will ensure the book’s place in their canon.

Whitney Phillips, attempting to articulate the emerging figure of the troll and its significance writes, ‘like all trolls, (infamous Redditor) Violentacrez shows us, purposefully or not, the underlying values of the host culture.’ Stewart Home’s intention is undoubtedly also to do this. My question is whether this strategy actually works in any useful way or whether it just perpetuates that culture. Transformation doesn’t seem to occur. Wes Craven remade Last House on the Left himself in 2009. Hollywood seems trapped in an endless loop of sequels, remakes and franchises. Culture eulogises itself obsessively, cult fan-boys bask in the light of a hall of mirrors held up to culture, summarise narratives on their blogs and cross reference every actor and piece of trivia like IMDB hasn’t already done it. Stewart Home writes a book about everything disintegrating into numbness, boredom and suicide. Templeton rewinds his favourite scenes again and again and again, mutilates his wife and mistress on camera and then blows himself up (Home’s appropriation of suicide bombing as a motif is incidentally totally and miserably shallow and colonialist and warrants its own essay).

Stewart Home may not like it, but he is part of mainstream culture. Those subcultural havens from before the internet exploded, the ones Home cut his teeth on, become ever less solid and they only ever housed the privileged few. Home may be a literary early adopter but that doesn’t mean he’s not part of the elite he so disdains. He’s a troll working in the idiom of fanfiction. In a way there’s more in common here with 50 Shades of Grey than American Psycho. The great novelisation of the history of horror movies may one day be written, may have already been written, but whether it’s written by some chick who works in the last video shop on earth and worships Boris Karloff or by a Hollywood insider, I hope it’ll have a narrative centred on something other than total disdain and referential point scoring. It’ll use horror as more than a narrative trope. When the great horror novel comes there’ll be a way for me to read it, a way through that doesn’t just feel like an extended and virtuouso series of in-jokes that I’m not invited to. In the year that Mandy, Charlie & Mary Jane was published the television maverick and film-maker Joss Whedon released the movie Cabin in the Woods, a spectacular parody of form which lampoons the horror genre complete with references to Michael Haneke’s chilling Funny Games, gender critique and all manner of cultural context including a pseudo Brechtian breaking of the fourth wall and references to ancient mythology. Whedon shamelessly continues to work in the mainstream while astutely maintaining rigorous criticality and a sense of joy and humour. As our media narratives break down under the pressure of globalised marketing it is clear to me that it is that shamelessness which is key, not Home’s exclusivity. There’s nothing shameless about Home’s attempt to pass judgement on a culture he seems so concerned with distancing himself from, so intent on denying his rarefied symbolic status within. It’s a denial only ever intended to increase that status.

If I’m right that horror is just a trope for Home, a carefully researched costume for Templeton, then this might explain the book's failure to actually do more than parrot out a greatest-hits-by-rote of the horror genre. People who love what they do (I swear, this isn’t about authenticity, it’s about motive) don’t care about being cult, they want everyone to love what they love, they are desperate to explain it. Preaching to a choir of apparent like minds, while potentially also quietly mocking them for enjoying your work and deriding in advance anyone who doesn’t is a ridiculous way to make art but more importantly seems like a half-arsed way of going about trying to destroy the novel-as-we-know-it. If you don’t want to blow everyone’s minds then you aren’t aiming near high enough.

Hestia Peppe is an artist and writer. She tends connections and keeps the homefires burning in South London. www.peepsgame.net

Info

Stewart Home, Mandy, Charlie & Mary-Jane, Penny-Ante Editions, March 2013.

Footnotes

1. http://www.opsonicindex.org/nonfiction/shinterview...

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com