University Struggles at the End of the Edu-Deal

As students around the world start to take action against national governments' university spending cuts, George Caffentzis sees a plane of struggle developing; one which acts against the crooked deal of high cost education exchanged for life-long precarity

We should not ask for the university to be destroyed, nor for it to be preserved. We should not ask for anything. We should ask ourselves and each other to take control of these universities, collectively, so that education can begin.

- From a flyer found in the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts originally written in the University of California

Since the massive student revolt in France, in 2006, against the Contrat Première Embauche (CPE), and the ‘anomalous wave' in Italy in 2008, student protest has mounted in almost every part of the world, suggesting a reprise of the heady days of 1968. It reached a crescendo in the Fall and Winter of 2009 when campus strikes and occupations proliferated from California to Austria, Germany, Croatia, Switzerland and later the UK. The website Tinyurl.com/squatted-universities counted 168 universities (mostly in Europe) where actions took place between 20 October and the end of December 2009. And the surge is far from over. On 4 March 2010, in the US, on the occasion of a nationwide day of action (the first since May 1970) called in defense of public education, one of the co-ordinating organisations listed 64 different campuses that saw some form of protest.1 On the same day, the South African Students' Congress (SASCO) tried to close down nine universities calling for free university education. The protest at the University of Johannesburg proved to be the most contentious, with the police driving students away with water cannons from a burning barricade.

At the root of the most recent mobilisations are the budget cuts that governments and academic institutions have implemented in the wake of the Wall Street meltdown and the tuition hikes that have followed from them; up to 32 percent in the University of California system, and similar increases in some British universities. In this light, the new student movement can be seen as the main organised response to the global financial crisis. Indeed, ‘We won't pay for your crisis' - the slogan of striking Italian students - has become an international battle cry. But the economic crisis has exacerbated a general dissatisfaction that has deeper sources, stemming from the neoliberal reform of education and the restructuring of production that have taken place over the last three decades, which have affected every aspect of student life throughout the world.2

The End of the Edu-Deal

The most outstanding elements of this restructuring have been the corporatisation of the university systems and the commercialisation of education. ‘For profit' universities are still a minority on the academic scene but the ‘becoming business' of academe is well advanced especially in the US, where it dates back to the passing of the Bayh-Dole Act of 1980, that enabled universities to apply for patents for ‘discoveries' made in their labs that companies would have to pay to use. Since then, the restructuring of academe as a money-making venture has proceeded unabated. The opening of university labs to private enterprise, the selling of knowledge on the world market (through online education and off-shore teaching), the precarisation of academic labour and introduction of constantly rising tuition fees forcing students to plunge ever further into debt, have become standard features of the US academic life, and with regional differences the same trends can now be registered worldwide.

In Europe, the struggle epitomising the new student movement has been against the ‘Bologna Process', an EU project that institutes a European Higher Education Area, and promotes the circulation of labour within its territory through the homogenisation and standardisation of schooling programs and degrees. The Bologna Process unabashedly places the university at the service of business. It redefines education as the production of mobile and flexible workers, possessing the skills employers require; it centralises the creation of pedagogical standards, removes control from local actors, and devalues local knowledge and local concerns. Similar developments have been taking place in many university systems in Africa and Asia (like Taiwan, Singapore, Japan) that also are being ‘Americanised' and standardised (for example, in Taiwan through the imposition of the Social Science Citation Index to evaluate professors) - so that global corporations can use Indian, Russian, South African or Brazilian, instead of US or EU ‘knowledge workers', with the confidence that they are fit for the job.3

It is generally recognised that the commercialisation of the university system has partly been a response to the student struggles and social movements of the '60s and '70s, which marked the end of the education policy that had prevailed in the Keynesian era. As campus after campus, from Berkeley to Berlin, became the hotbed of an anti-authoritarian revolt, dispelling the Keynesian illusion that investment in college education would pay down the line in the form of an increase in the general productivity of work, the ideology of education as preparation to civic life and a public good had to be discarded.4

But the new neoliberal regime also represented the end of a class deal. With the elimination of stipends, allowances, and free tuition, the cost of ‘education', i.e. the cost of preparing oneself for work, has been imposed squarely on the work-force, in what amounts to a massive wage-cut, that is particularly onerous considering that precarity has become the dominant work relation, and that, like any other commodity, the knowledge ‘bought' is quickly devalued by technological innovation. It is also the end of the role of the state as mediator. Students in the corporatised university now confront capital directly, in the crowded classrooms where teachers can hardly match names on the rosters with faces, in the expansion of adjunct teaching and, above all, in the mounting student debt which, by turning students into indentured servants to the banks and/or state, acts as a disciplinary mechanism on student life, also casting a long shadow on their future.

Still, through the 1990s, student enrolment continued to grow across the world under the pressure of an economic restructuring making education a condition for employment. It became a mantra, during the last two decades, from New York to Paris to Nairobi, to claim that with the rise of the ‘knowledge society' and information revolution, cost what it may, college education is a ‘must' (World Bank 2002). Statistics seemed to confirm the wisdom of climbing the education ladder, pointing to an 83 percent differential in the US between the wages of college graduates and those of workers with high school degrees. But the increase in enrolment and indebtedness must also be read as a form of struggle, a rejection of the restrictions imposed by the subjection of education to the logic of the market, a hidden form of appropriation, manifesting itself in time through the increase in the numbers of those defaulting on their loan repayments.

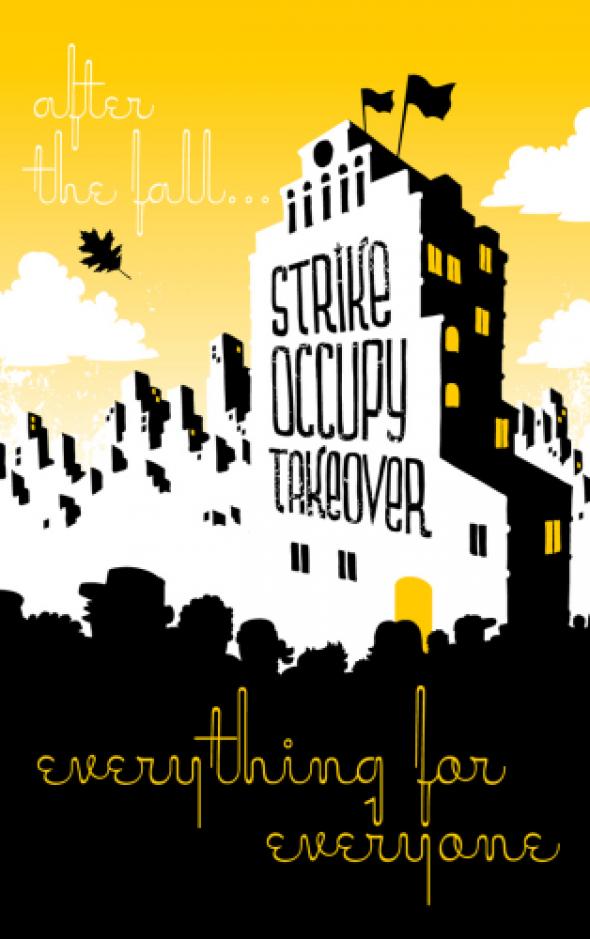

Image: Anarchist student solidarity poster

There is no doubt, in this context, that the global financial crisis of 2008 targets this strategy of resistance, removing, through budget cutbacks, layoffs, and the massification of unemployment, the last remaining guarantees. Certainly the ‘edu-deal', that promised higher wages and work satisfaction in exchange for workers and their families taking on the cost for higher education, is dissolving as well. In the crisis capital is reneging on this ‘deal', certainly because of the proliferation of defaults and because capitalism today refuses any guarantees, such as the promise of high wages to future knowledge workers.

The university financial crisis (the tuition fee increases, budget cutbacks, furloughs and lay-offs) is directly aimed at eliminating the wage guarantee that formal higher education was supposed to bring and at taming the ‘cognitariat'. As in the case of immigrant workers, the attack on the students does not signify that knowledge workers are not needed, but rather that they need to be further disciplined and proletarianised, through an attack on the power they have begun to claim partly because of their position in the process of accumulation.

Student rebellion is therefore deep-seated, with the prospect of debt slavery being compounded by a future of insecurity and a sense of alienation from an institution perceived to be mercenary and bureaucratic that, into the bargain, produces a commodity subject to rapid devaluation.

Demands or Occupations?

The student movement, however, faces a political problem, most evident in the US and, to a lesser extent, in Europe. The movement has two souls. On the one side, it demands free university education, reviving the dream of publicly financed ‘mass scholarity', ostensibly proposing to return to the model of the Keynesian era. On the other, it is in revolt against the university itself, calling for a mass exit from it or aiming to transform the campus into a base for alternative knowledge production that is accessible to those outside its ‘walls'.5

This dichotomy, which some characterise as a return to the ‘reform versus revolution' disputes of the past, has become most visible in the debate sparked off during the University of California strikes last year, over ‘demands' versus ‘occupations', which at times has taken an acrimonious tone, as these terms have become complex signifiers for hierarchies and identities, differential power relations, and consequences for risk taking.

The contrast is not purely ideological. It is rooted in the contradictions facing every antagonistic movement today. Economic restructuring has fragmented the workforce, deepened divisions and, not least, it has increased the effort and time required for daily reproduction. A student population holding two or three jobs is less prone to organise than its more affluent peers in the '6os.

At the same time there is a sense, among many, that there is nothing more to negotiate, that demands have become superfluous since, for the majority of students, acquiring a certificate is no guarantee for the future which promises simply more precarity and constant self-recycling. Many students realise that capitalism has nothing to offer this generation, that no ‘new deal' is possible, even in the metropolitan areas of the world, where most wealth is accumulated. Though there is a widespread temptation to revive it, the Keynesian interest group politics of making demands and ‘dealing' is long dead.

Thus the slogan ‘occupy everything': occupying buildings being seen as a means of self-empowerment, the creation of spaces that students can control, a break in the flow of work and value through which the university expands its reach, and the production of a ‘counter-power' prefigurative of the communalising relations students today want to construct.

It is hard to know how the ‘demands/occupation' conflict within the student movement will be resolved. What is certain is that this is a major challenge the movement must overcome in order to increase its power and its capacity to connect with other struggles. This will be a necessary step if the movement is to gain the power to reclaim education from the hands of the academic authorities and the state. As a next step there is presently much discussion about creating ‘knowledge commons', in the sense of creating forms of autonomous knowledge production, not finalised or conditioned by the market and open to those outside the campus walls.

Meanwhile, as Edu-Notes has recognised,

already the student movement is creating a common of its own in the very process of the struggle. At the speed of light, news of the strikes, rallies, and occupations, have circulated around the world prompting a global electronic tam-tam of exchanged communiqués, slogans, messages of solidarity and support, resulting in an exceptional volume of images, documents, stories.6

Yet, the main ‘common' the movement will have to construct is the extension of its mobilisation to other workers in the crisis. Key to this construction will be the issue of the debt that is the arch ‘anti-common', since it is the transformation of collective surplus that could be used for the liberation of workers into a tool of their enslavement. Abolition of the student debt can be the connective tissue between the movement and the others struggling against foreclosures in the US and the larger movement against sovereign debt internationally.

Acknowledgements

I want to thank the students and faculty I recently interviewed from the University of California, the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna and Rhodes University in South Africa for sharing their knowledge. I also want to thank my comrades in the Edu-Notes group for their insights and inspiration.

George Caffentzis <gcaffentz AT aol.com> is a member of the Midnight Notes Collective. Together with the collective, he has co-edited two books, Midnight Oil: Work Energy War 1973-1992 and Auroras of the Zapatistas: Local and Global Struggles in the Fourth World War. Both were published by Autonomedia Press

Footnotes

1 See, http://defendeducation.org

2 Edu-Factory Collective, Towards a Global Autonomous University, Brooklyn, NY: Autonomedia, 2009.

3 See, Silvia Federici, George Caffentzis, Ousseina Alidou, A Thousand Flowers: Social Struggles Against Structural Adjustment in African Universities, Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press, 2000, Richard Pithouse, Asinamali: University Struggles in Post-Apartheid South Africa, Trenton: Africa World Press, 2006 and Arthur Hou-ming Huang, ‘Science as Ideology: SSCI, TSSCI and the Evaluation System of Social Sciences in Taiwan', Inter-Asia Cultural Studies, Volume 10 2009, Number 2, pp. 282-291.

4 George Caffentzis, ‘Throwing Away the Ladder: The Universities in the Crisis', Zerowork I, 1975, pp. 128-142.

5 After the Fall: Communiqués from Occupied California, 2010, Accessed at www.afterthefallcommuniques.info

6 Edu-Notes, ‘Introduction to Edu-Notes', unpublished manuscript.

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com