The Ghosts of Participation Past

Buy on Amazon UK £9.99 and other regions, Super Saving free shipping.

As the financial crisis fastens its grip ever tighter around the means of human and natural survival, the age of the algorithm has hit full stride. This phase-shift has been a long time coming of course, and was undoubtedly as much a cause of the crisis as its effect, with self-propelling algorithmic power replacing human labour and judgement and creating event fields far below the threshold of human perception and responsiveness.

Claire Bishop's new book, Artificial Hells, considers the history of participation as an organising principle of avant-garde art, but also of liberal democracy. Review by Josephine Berry Slater

Nearly 400 pages long, bearing an arresting title and featuring a picture of a mounted policeman directing a crowd inside the Tate Modern, Claire Bishop's latest book seems to demand our full attention. With participation as its key subject, this impressive survey of its developmental role within art practice is set to be a key reference text for some time to come. But what does this buzzword 'participation' really mean after all? Is it a euphemism that sells the obligation to cooperate, to play along? Is it a moral imperative, a condition of the social? Is it just a way of emphasising the necessarily plural nature of activity in general? Can it describe the active contemplation of something without any expressive extension, or does it demand the extension of thought outwards, the connection of thought to action? This loose concept, used as a thread to connect some of the most uncompromising art of the 20th and early 21st century in Bishop's Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship, remains all too elusive. As does the implication of its title, for Bishop is in no simple sense condemning what has by now become a default virtue of 'progressive art', as one might infer. Instead, Artificial Hells, which takes its name from an essay by André Breton dissecting a disappointing Dada action in a Paris churchyard in 1921, opens up the aesthetic politics of art works that depend upon more or less active audiences to a wide, but sometimes vague, horizon of consideration.

If the term 'participation' might seem to lock work from distant eras into the concerns of contemporary aesthetics, then it is nevertheless a great achievement of Bishop's book that the application of this term opens channels into aesthetic and political conundrums as old as antiquity. Bishop isn't interested in dealing with the limited scope presented by Nicolas Bourriaud in his epoch flattening concept 'relational aesthetics', used to define art that takes social relations as its medium albeit within the limits of the art world's pain tolerance. Instead, she largely departs from the heavily rotated hits of western art history to uncover what artists' desires to activate spectators might have meant in the different moments and political geographies of modernity. In her exhaustive trawl, which she has been undertaking since 2004 – funded by a series of research grants and residencies which glimmer like sinking treasure in the straits of 2012 – she focalises three historical moments in which social upheaval fuelled the desire to bring art and life into catalytic proximity.

The first is the fascist and communist convulsions of Europe c.1917, the second is the build up to May '68 in Europe but significantly also South America, and the last is the resurgence of participatory art before and after the fall of the Wall in '89, as artists from the former East came into contact with the West. Despite this historical and geographical breadth, the main connective work she performs between aesthetic and economic relations centres on Britain's transition into neoliberalism. Here she uses a close reading of the Artist Placement Group and its pioneering of industrial placements from the late 1960s, as well as the journey of community arts from self-instituting power to state-complicit extension of social work, as switch-points for the subsumption of radical aesthetic agendas into the creative economy which would become a fig leaf for post-Fordist restructuring.

Image: Milan Knížák, Stone Ceremony, 1971

'Participatory art', in Bishop's account, can therefore be used to bracket together a dizzyingly diverse set of experiments. Her conceptual web binds together such multi-scalar events as: the 1920 reenactment of the storming of the Winter Palace, directed by Nikolai Evreinov, and involving 8000 participants and 100,000 spectators; Czech artist Milan Knížák's 1971 piece Stone Ceremony in which a handful of participants stood silently inside circles made of stones in a remote landscape; or Marina Abramovic's untitled piece for MoCa Los Angeles' annual gala in 2011, in which performers kneeling under tables graced by glitterati poked their heads through holes to create living table ornaments. It might come as no surprise, given this categorical elasticity, that Bishop fails to generate either a compelling definition of participatory art, or a coherent optic through which to read the desire to fuse art with the living in the fascinating material she assembles.

But what could such a connective reading entail? A key ground to this discussion which cries out for exploration is the scale of the reversal from older aesthetic orders to this one and what broader shifts this reversal expresses. Reading Hannah Arendt's The Human Condition directly after putting down Artificial Hells, I began to understand the degree to which the earliest aesthetic philosophy took a diametrically opposed position. In a nutshell, the serene contemplation required for the production and enjoyment of 'the beautiful' demanded inactivity, and relegated activity to the realm of bodily necessity and the labour of sustaining life (the oikos) which was performed by slaves and women, of course.1 The cultivation of beauty and the quest for immortality through great works and deeds were arrived at through non-coerced activity and placed on the side of freedom, whereas the productive activities relating to the necessities of the body, the economy and later even politics, were placed on the side of heteronomy or unfreedom. This freedom, however, was predicated on slavery. The aesthetic elevation of inactivity continued through the mid-18th century, culminating in Denis Diderot's pre-revolutionary advocacy of 'absorption'. France's foremost art and theatre critic found in this attribute the defining characteristic of the arts, both in the subjects depicted and in the experience of the spectator who should be drawn away from the circumstances of spectating into a 'repos delicieux'.2 Diderot even advised that theatre should be produced and acted as if a wall had been erected between the stage and the audience. The means of appearance should on no account be allowed to appear for fear the spell of the repos may be shattered. And indeed the spell was shattered by the French Revolution, through which the art work began to open up to the contingent dynamics and uncertainties of action – be that of the subjects represented, the means of representation themselves or ultimately the art object's dematerialisation into a field of action. This brief sketch starts to give 'participation' some stronger historical coordinates, and could be interestingly pursued into the contemporary paradox of participation as agent of normativity. One begins to see that participation for-itself implies the outward dramatisation of activity, or the staging of action and its consumption, since contemplation without externalisation can't be counted as an active enough engagement. It seems important, therefore, that we connect 'participative art' to a broader fetishisation of action within modernity's generalisation of labour.

Image: Marina Abramovic, Untitled Performance for MOCA Los Angeles annual gala, 2011

Everywhere throughout modernity, as Bishop's book amply demonstrates, the values of classical aesthetics have been overthrown. Filippo Marinetti wanted audiences to end their passivity and develop 'commitment to a cause' through violent participation, delivering themselves up to the art work 'heart and soul'. The sensationalism of the Futurist serate, staged at music halls, were designed to antagonise and exhilarate the audience whose seats were sometimes covered in glue, tickets' oversold, and who were treated to spectacles of monstrosity, slapstick and gymnastics. They duly responded, with one audience member handing Marinetti a pistol and inviting him to kill himself on stage, while others blew car horns or threw rotten eggs and vegetables. A ritualised slanging match which would have made Diderot rotate in his grave. Platon Kerzhentsev, Proletkult's3 theoretician of theatre, didn't want people to say 'I am going to see something' but 'I am going to participate in something'; generally didactic retellings of the triumphant progress of the class struggle. Groupe Recherche d'Art Visuel, the Paris-based '60s art collective, wrote a manifesto declaring that audiences should be 'made' to participate, and then solicited passers by to balance on 'permutational sculptures' reminiscent of soft-play centres. The Argentinian collective who mounted the Cycle of Experimental Art in Rosario in 1968, the year of General Ongania's military coup, made work which 'obliged' audiences 'violently to participate'. In a famous work by Graciela Carnevale gallery visitors were locked into a room with a shop-front window, and only escaped when a passer-by smashed the glass. The Brazilian director Augusto Boal, acting against the notion that catharsis in classical theatre was merely a means to maintain the status quo, declared, 'I don't want the people to use the theatre as a way of not doing in real life'. These are just some of the more striking of many calls to action which crowd the pages of Artificial Hells – the list is potentially endless, and Bishop certainly brings it up to the present.

So how then does she explain this reversal by which contemplation, and indeed beauty, are relegated and the activation of the spectator turned into an article of faith? Rather than creating any synthetic or developmental analysis, she chooses to concentrate instead on the radical ambivalence of artists' desire to provoke participation in works scattered across the 20th century. Participation metastasises across contexts, always differently inflected and drawing with it a number of contradictions. Be that as it may, the book nevertheless registers a general shift in audience participation from crucial ingredient and aim of revolutionary and radical cultures to state-endorsed language of post-Fordist conformity. Bishop clearly articulates New Labour's 'social inclusion' policies (which she understands, properly, as the rhetorical elision of class and class tensions, used to deflect attention away from the roll-back of the welfare state and the introduction of privatised risk) as a capitalist appropriation of radical culture's fostering of participative self-actualisation. 'To be included and participate in society means to conform to full employment, have a disposable income, and be self-sufficient', she says.4 What is perplexing though, is that despite fully grasping the political use of participation as euphemism for work, Bishop holds this understanding separate from her reading of the aesthetics of late and postmodernity. The general apotheosis of labour and productivity embodied in modernity, be that capitalist or socialist, isn't sufficiently connected to a reading of the aesthetic apotheosis of participation.

Image: Gerardo Dottori, Futurist Serata in Perugia, 1914

Bishop is also fiercely critical of the parallel appropriation of a once subversive tendency by a liberal art world which fetishises utilitarian art that operates 'directly' upon social life, producing a manifold of 'modest gestures'. This liberal regime, she claims, tends to a suspicion of aesthetics and aesthetic judgements (something that Bishop repeatedly champions without really explaining what happens to aesthetics when the art work dematerialises into situations nor how judgement might work in post-Duchampian art) and promotes, instead, the 'ethical work'. But this liberal regime doesn't actually go so far as to compare art works with non-art works on a 'scale of effectiveness'. As Bishop observes, art works are only compared with other art works. In this way, it would seem, autonomy is snuck back in through the back door; art continues to coast on its old privileges but can't admit to them. However, she doesn't say this. Instead, Bishop leans heavily on Rancière's argument made in his Malaise dans l'esthetique. The exemplary ethical gesture in art, she explains via Rancière, works to blur the political and the aesthetic (in ways that seem to repeat the gesture of neoliberalism's call for social inclusion). This is achieved,

by replacing matters of class conflict with matters of inclusion and exclusion, [contemporary art] puts worries about the 'loss of the social bond', concerns with 'bare humanity' or tasks of empowering threatened identities in the place of political concerns. Art is summoned thus to put its political potentials at work in reframing a sense of community, mending the social bond, etc. Once more, politics and aesthetics vanish together.5

Although she says that Rancière's account leans too heavily on Bourriaud's relational aesthetics, and is unfair to much contemporary work, she nevertheless seems satisfied with his account of the depoliticised yet ethical art work.

This easy acceptance could offer another clue to what could uncharitably be described as the missing spine of Artificial Hells. By counterposing class conflict as properly political against the toothless ethics of 'bare humanity', it seems that Rancière, and Bishop with him, are missing a key ground of struggle and hence politics – namely 'bare life' and the sphere of necessity itself. Bishop often uses the term 'social justice' when wishing to invoke politics – a term that refers us to a liberal political imaginary of human rights guaranteed, ultimately, by citizenship and the rule of law. A position which is unable to grasp the role of the modern nation state in producing structural exclusions from the sphere of the 'community', let alone that of politics, based on the inherently jingoistic horizon of popular sovereignty; something Foucault calls simply 'state racism'. When sovereignty is distributed to the People who become its referent, the fact of their birth in the territory of the state becomes all important (nascere, meaning 'to be born', is also the root of 'nation'). A clue that Giorgio Agamben seizes upon in his exploration of the biopolitical nature of modern democracies. While life, now reconfigured as the basis of sovereignty, is in this respect liberated and endowed with rights, it is also brought into the calculus of politics and economics as never before. As Agamben explains, '[modern democracy] wants to put the freedom and happiness of men into play in the very place – "bare life" – that marked their subjection.' Thus for Agamben, the fatal 'aporia' of modern democracy – which cannot endow all life with rights, but wants to decide on which life is worthy – gives rise to totalitarian and liberal regimes simultaneously. In a related development, the gesture of distributing authorial control into the popular body of the audience could be said to exert a more invasive control over the site of its former subjection – namely the privacy and muteness of contemplation and the spectator's free disposition over their own activity. The elevation of participation, then, seems deeply linked to this redistribution of sovereignty, both in the ubiquity of state-capitalist decisions over deserving and undeserving forms of life, and through the aesthetic conscription of parts of our deserving interiority in the co-production of expression. A sorting activity between subjects, their forms of activity and their internal states which, in the worst cases, is unthinkingly extended by the ethical utilitarianism of relational aesthetics or repeated, if hopefully with a knowing nod, by the lugubrious integration of living ornaments into the scaffold of ruling class enjoyment.

The participative art discussed in Bishop's book can be found on either side of this border between totalitarianism and liberalism, and much of it likewise contests life's exploitation or valorisation and looks to free it. It is often the work that emerges in the countries where people are apparently less free that, for me at least, proved the most incisive in revealing the increasing state and/or capitalist extension of control over life. The heart of the book, and the way in which it helps to remake the contemporary art map, entails Bishop's surveys of South American art of the late '60s and that of Eastern Europe in the '60s-'80s. In both territories, and in totally different ways, artists opened up the ambivalence of participation, often making today's relational art look naive and unhistorical by comparison.

Targeting the media construction of 'immediacy' and especially the celebration of bohemian happeners, the Argentinian artist Oscar Masotta, running on a heavy dose of post-structuralist theory, formed El Grupo de los Artes de los Medioa Masivos in 1966. Their first decidedly 'cool' work, Total Participation, was a spoof event relayed to the media through a series of photographs of revelling hipsters. The pictures were duly printed by the Argentinian press and sensationalised as a bone fide event. But if this exposé of the artifice of vitality was both edifying and amusing, the piece To Induce the Spirit of the Image, made by Masotta later in the year in the lead up to General Ongania's military coup, stands as one of the most affecting works discussed in this book. The construction of vitality gives way to the exploration of 'living currency', the weighing of life as value. In this piece, 20 elderly people were paid to stand in a storage room in front of an audience, and subjected to fire-extinguishers, a high-pitched noise and blinding white light. At the beginning of the event, Masotta lectured the audience on control and reminded them that they'd paid 200 pesos to watch, while the performers had been paid 600. In a later text entitled 'I Committed a Happening' Masotta commented: 'I felt as though something had slipped loose without my consent, a mechanism had gone into motion.'6

Image: Oscar Massotta, To Induce the Spirit of the Image, 1966

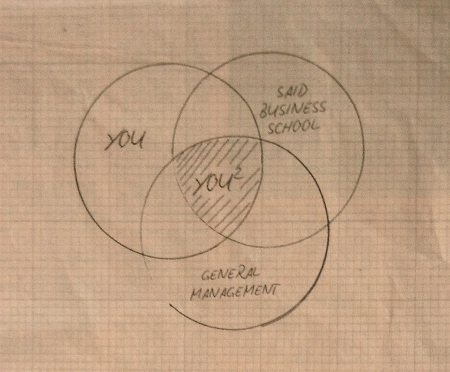

Amongst other things, this motion describes the automatism of exchange value which convinces us that simply everything, even suffering, can be bought and sold. Accepting the spectacle of others' suffering is made to seem reasonable through this logic which has been massaged into our psyches from birth. The commodity form extends n-dimensionally and it hasn't stopped at the human being, whose labour power has long ceased to be the limit of capital's interests. And if everything is coloured by exchange value, then our self-relation is no exception. A truth revealed with its usual brute elegance by the advertising industry in a recent ad for the Said Business School. A Venn diagram of the part of 'you' that also overlaps with the set of 'general manager' is overlaid onto another set which is the business school – an overlap of resources which gives rise to a 'you2'. The regime of human capital and self-appreciation is one in which activity is reversed from the despised lot of slaves to become the aspiration of every self-respecting soul and ethical artist. The problem, both for art and politics, is that activity both secretes value as well as making art or politics possible at all through the human capacity to begin something, to appear, or to trigger 'social action'. Of course the art world has become the smelting pot of appearance and action, efficiently forging resistant activity into creative capital. Today, it comes as no surprise to see photos of Santiago Sierra's (heavily Masotta inspired) act of 'social sadism' – the tattooing of a single line across a row of paid human backs – in a Barclays Bank sponsored exhibition at Autograph's Rivington Place gallery this summer.7 Masotta's strategy of making 'social sadism explicit' by redistributing it from the field of state control and capitalist social relations to that of art seems to have become disturbingly ineffectual. Perhaps this is because we regard ourselves as human capital as never before, due in no small part to the appreciation of creativity as an individual capacity of the highest worth. Today, social sadism and individualistic creativity have become two sides of the same biopolitical coin.

Image: Said Business School advertisment, Financial Times, September 2012

If the creative economy represents the high-water mark of a self-appreciative elevation of activity, then the USSR could be said to have forked the apotheosis of labour into a distinct but related development. State socialism's religiose celebrations of heroic proletarian productivity were directed towards a non-personal, (inter)national form of appreciation. Undoubtedly these concussive paeans to glorious labour triggered a more reclusive and tentative kind of participative art which took place in apartments, involved surreptitious acts of nomination, hacks of the parcel service, or walks in the countryside. Strangely, given Bishop's critiques of the utilitarianism of the 'ethical' art work that aims to effect 'social change', it is her reading of these more reclusive works that falls furthest of her own mark. Of the Czech artist Milan Knížák, whose work developed from a fluxus-inspired ludic street improvising, through absurdist instructional works to increasingly introspective pieces such as Stone Ceremony, she remarks:

One should resist the temptation to make leftist political claims for this non-conformity: the work sprang from an existential impulse, seeking to generate a territory of free expression, a celebration of idiosyncrasy rather than social equality.8

Her counterposing of free expression and social equality reveals the extent to which she seems not to have conceived a politics of the subject, a crucial point of intersection for her parallel exploration of the 'commodification of human bodies in a service economy' and the conscription of participation into politics and art. She compounds this problem by disparaging Knížák's public Letter to the Population as ‘nonsensical’, from which it is hard not to infer that she finds this project too absurd to be 'socially useful'. His instructions such as ‘Do not drink at all for 3 days’ or ‘Commit suicide!’ are not allowed the interpretive generosity of perhaps parodying reasonable social commands such as those crystallised in the Said Business School ad, or of the too beatific instructional works of US fluxus artists like Yoko Ono. Or, more tendentiously, this work could be read as proposing a politics of the 'human strike' avant la lettre; something being worked on by artists and political theorists today in thinking routes out of total reification. With Knížák's piece An Event for the Post Office, the Police, and the Occupants of no.26 Vaclavkova Street, Prague 6, and all Their Neighbours, Relatives and Friends (1966), she asks ‘What were his criteria of success for such a piece? Since none of the participants actually went to the cinema, did he consider his work to be a failure?’9 'Criteria of success' sounds more like a policy impact assessment exercise than an aesthetic judgement.

The Collective Action Group, Ten Appearances, 1981

In Ten Appearances (1981), another Soviet piece explored by Bishop, by the Collective Actions Group, a small handful of participants gathered in a field outside Moscow, each holding a string of 2-300 metres attached to a board. They were instructed to walk outwards while unwinding it in different directions towards the forest at the edge of the field. At the end of the thread was a piece of paper bearing a 'factographic' text: the name of the organisers, time, date and place of the action. From here the participants needed to decide for themselves what to do next: some continued walking and got on a train back to Moscow, others rejoined the group. Those who returned were given photographs of themselves appearing from a forest, taken a few weeks earlier, but indistinguishable from this forest. This piece doesn't give rise to 'unified collective experience' writes Bishop, but 'difference, dissensus and debate: a space of privatised experience, liberal democratic indecision, and a plurality of hermeneutical speculation'.10 She then quotes the group's key theorist Andrei Monastrysky explaining how the work's engagement of the participant differs from the 'tunnel vision' of Stalin or Brezhnev era aesthetic contemplation:

when one comes to a field – when one comes there, moreover, with no sense of obligation but for private reasons of one's own – a vast flexible space is created, in which one can look at whatever one likes. One's under no obligation to look at what's being presented – that freedom, in fact, is the whole idea.11

This near concurrence, but ultimate clash, of interpretations reveals both the potentials and shortcomings of Artificial Hells. Where the British art theorist apparently wants the same thing as the Russian, namely dissensus as a means to deflect the conscription of art and experience to social programmes, she nevertheless closes down the space of its appearance into liberal-democratic contours in which 'private' is read as 'privatised' and 'whatever one likes' becomes political 'indecision'. In this seemingly slight mutation we can find evidence of a too dualistic reading of interiority as individual, and exteriority as social. If this logic is ramified, it leads to the conclusion that what (not who) we are is the property of ourselves (on which we'd be mad not to speculate), and what can be considered social is that which is divisibly external to the self. At another point Bishop calls this era of Soviet apartment-art 'metapolitical' in Rancière's sense of creating a 'redistribution of the sensible' rather than assuming an 'identifiable (and activist) political position'. What she misses here too is that activist politics has also been working with a 'metapolitical' multiplication of 'private' experience during the same historical time-span, showing not only how 'the personal is political', but also how new publics can be built through the appearance of private experience. In this sense appearance and action as well as self and other become inextricably entwined. And if appearance is in part conditional on the inactivity of private thought as well as an externalisation incited by the web of social relations, then this may also be a route out of the fetishism of a participation for its own sake, that causes nothing but its own being active to appear.

Josephine Berry Slater is editor of Mute and co-author with Anthony Iles of No Room to Move: Radical Art and the Regenerate City, 2010

Info

Claire Bishop, Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship, London and New York: Verso, 2012

Footnotes

1 In classical Greece activity itself was actually considered antithetical to the experience of thought and beauty to which aesthetics belongs. For Aristotle, what distinguishes us humans from our animal counterparts are the ways we are able to live which are free of the work and labour induced by necessity. Unlike the slave, artisan or merchant who had 'lost the free disposition of their movements', the three bioi, forms of life enjoyed only by the citizens, were concerned with the beautiful (the life of enjoying bodily pleasures in which the beautiful is consumed, the life devoted to matters of the polis, in which excellence produces beautiful deeds and the life of the philosopher devoted to the inquiry into and contemplation of things eternal.) Increasingly in late antiquity, contemplation was isolated and identified as a higher form of (nevertheless bodily) existence distinguished from the vita activa; the philosopher, as advocated by Plato, lived in 'complete quiet' and, somewhat enigmatically, it was 'only his body which inhabits the city'. See Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition, (1958), The University of Chicago, 1998, p.12 and p.16.

2 See Michael Fried, Absorption and Theatricality: Painting and Beholder in the Age of Diderot, Chicago University of Chicago Press, 1988.

3 Proletkult was a revolutionary arts institution established in Soviet Russia to develop new, revolutionary working class aesthetics worthy of the revolution.

4 Claire Bishop, Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and The Politics of Spectatorship, London and New York: Verso, 2012, p.14

5 Rancière, cited in ibid., p.28.

6 Masotta cited in ibid., p.109.

7 Autograph ABP's Roma-Sinti-Kale-Manush, was at Rivington Place, London 25 May - 28 July, 2012.

8 Bishop, op. cit., p.134.

9 The event targeted an apartment building in Prague at random. The residents were subjected to three types of intervention: being sent packages in the post containing oddities such as lumps of bread; being confronted with a strange assortment of objects in the communal parts such as goldfish or unmade beds; and finally being were sent free cinema tickets to a movie, where they would ideally sit together due to the seat reservations. Ibid., p.136.

10 Ibid., p.160.

11 Monastyrsky, cited in Bishop, p.160.

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com