WSIS Vol.1: Behind the Great Wall

Hailed as the first UN world conference to incorporate a 'multi-stakeholder' approach, the World Summit on the Information Society completed its first phase last December. Alistair Alexander looks at what its controlled confines meant for the civil society contingent

> Webcams at WSIS registration desks. Photo: nodo50.org

> Webcams at WSIS registration desks. Photo: nodo50.org

For its supporters, the World Summit on the Information Society (WSIS), held in Geneva from 10 –12 December, presented a unique opportunity to forge a global technology development agenda out of the much-hyped information revolution. And with over 10,000 delegates from 174 countries attending the summit, security was on the tight side – after all, you can't take any chances these days.

Delegates patiently queued to pass through banks of metal detectors; pockets were emptied; glasses and even shoes were removed. Along with the obligatory shoulder-bags of mission statements, action plans and floorplans, summit-goers were given digital photocards that were scanned and logged as they entered.

It was only after the summit had finished that some researchers discovered the security measures went considerably further than advertised. Embedded in each photo ID card – to be worn at all times, of course - was a radio-frequency identification chip or RFID; a covert device that could track the movements of every delegate.

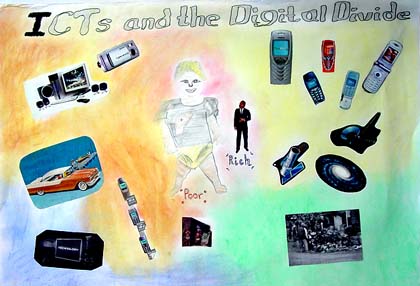

WSIS was announced in 1998 by the United Nations as a summit to address every imaginable issue raised by the hi-tech transformation of the global economy. Not only did the summit plan to close the global digital divide between the information rich and poor, but it was going to secure information access for all and reclaim administrative control of the internet from the US Department of Commerce.

Delegates spoke excitedly in the techno-utopian language of 'digital empowerment', 'e-transformation' and 'scalable development networks'. But anyone assuming that human rights were relevant to the WSIS vision of an information society would have been swiftly disabused of the notion.

Like the swipe cards, a different agenda had been deeply embedded in the WSIS process; one where network information technology is increasingly being deployed as a powerful instrument of state and corporate control.

> A delegate's data on the WSIS central database. Photo: nodo50.org

> A delegate's data on the WSIS central database. Photo: nodo50.org

In the WSIS Plenary Hall, the geographical and political centrepiece of the summit, an endless procession of representatives from some of the world's most repressive regimes earnestly pledged their support for the WSIS vision of the information society to polite ripples of applause.

The head of the Myanmar delegation, for example, called for an information society 'for the common good of all mankind' - a tall order in his particular nation, where the population faces a 15-year prison sentence for unauthorised possession of a fax machine.

The President of Tunisia was also keen to express his commitment to human rights, but in a way that 'consecrates freedom of expression and ensures the respect of state sovereignty'.

In Tunisia, like in so many other countries prominent at the summit, internet use is closely controlled and monitored by the state. Only two companies provide internet access; one is state-owned, the other has close ties to the government. In June 2002, the Government imprisoned Abdullah Zouari for editing Tunezine, a website critical of the government.

An unfortunate development – not least because Tunisia is hosting the second and concluding leg of WSIS in 2005.

But then, as Tunisian journalist and human-rights acitivist Souhayr Belhassen told a fringe meeting at the summit, 'For many of the countries here, the information society is simply a technical issue. When they talk about information they mean information disseminated from the centre to the periphery.'

> Poster by secondary school student from Ghana, for the WSIS Poster Competition

> Poster by secondary school student from Ghana, for the WSIS Poster Competition

No country exemplifies this approach more than China, whose influence could be felt everywhere at WSIS.

'While freedom of speech should be guaranteed and right safeguarded,' the Chinese Minster of Information told delegates, 'social responsibilities and obligations should also be advocated.'

China’s initial response to the internet was the 'great cyber wall' strategy, where China virtually sealed itself off from the internet to protect its citizens from anti-revolutionary propaganda. But in the late nineties, the Chinese authorities had a change of heart. Aware that being offline was holding back its rapidly developing economy, China developed a new policy: the 'Golden Shield'. In this new strategy, the internet would be embraced - but with draconian restrictions.

China likes to refer to its approach as 'informatisation'. The telecom infrastructure, provided by corporations such as Nortel Networks, has been constructed with state-of-the-art spyware installed on servers and routers throughout the network . A team of over 30,000 'cyber-police' monitor all online content and communication, looking for any material that might be considered a risk to 'state security'. Websites considered subversive are blocked – particularly those covering human rights, Taiwan and the Falun Gong.

In addition all Internet Service Providers in China, including AOL and Yahoo!, have signed 'pacts of self-discipline' with the Chinese state. The pact compels them to police their message boards, email and content and to hand over any potentially subversive materials to the Chinese authorities.

It is a strategy that has been startlingly successful. China is now regarded as the new commercial frontier - online as much as offline. But at least 42 people have been jailed for posting 'subversive' information on the internet.

> X-Ray and metal screening at WSIS entrance. Photo: nodo50.org

> X-Ray and metal screening at WSIS entrance. Photo: nodo50.org

For many delegations at WSIS, China ‘s informatisation provides the ideal model – rapid technology development while extending and consolidating state control.

'They're using ICT (information and communication technology) to modernise,' says Sharon Hom of Human Rights in China (HRIC), 'but they're also discovering very quickly very sophisticated technological ways to control, suppress and invade all corners of privacy that might be used for dissent.'

HRIC has been closely monitoring China's internet security regime and campaigns to free internet dissidents, such as Liu Di, who posted on the internet using the name 'Stainless Steel Mouse'. Hom was expecting to represent HRIC at WSIS, but HRIC's application was blocked without explanation.

'Being part of a big international UN meeting is very important to China and so they want to control who else can come,' she says. Hom attended the summit as part of another delegation.

Reporters Without Borders, who campaign vigorously for imprisoned journalists and human rights were also excluded from WSIS. Their response was the pirate Radio Non Grata, which broadcast into Geneva before it was shut down by police.

> Poster by secondary school student from Ghana, for the WSIS Poster Competition

> Poster by secondary school student from Ghana, for the WSIS Poster Competition

Critics within the WSIS process and activists on the outside saw the summit as a vehicle to advance the neo-liberal agenda into the third world's threadbare ICT infrastructure. Certainly the WSIS agenda was configured to attract the attention of western powers and technology corporations. But, at the summit itself, hi-tech corporations were conspicuous by their absence.

When the summit was first planned five years ago, the dotcom frenzy was shifting into pseudo-revolutionary pan-global overdrive. WSIS had hoped to harness the hi-tech hysteria to ensure no country got left behind as the information tidal wave surged across the world.

Implicit, of course, in the WSIS agenda was acceptance of the corporate priorities that drove the hi-tech bubble. For the techno-evangelists, the internet rendered the nation state obsolete; an analogue anachronism in the brave new digital world. But in corporate boardrooms, states still had a valuable function – to facilitate the swift transfer of telecom infrastructure into private, and thereby western ownership. To attract private capital WSIS had to play the corporate game; leaders from developing nations would need to prostrate themselves before their corporate benefactors to attract the investment they required.

Co-opting the nineties management-speak beloved of corporations and third-way governments alike, WSIS would address these issues through a 'multi-stakeholder' framework where developed and developing nations, the 'corporate community' and 'civil society' – i.e. NGOs - would come together in one all-encompassing event to hotwire the planet.

But that was before trillions of dollars was wiped off NASDAQ in the largest financial crash in history. Technology companies woke up to the fact they had blown billions of fraudulently acquired dollars on redundant infrastructure.

These days, the corporate titans no longer feel like evangelising about the global internet revolution; they're too busy salvaging their share options at home to go looking for new markets abroad. Besides, if technology corporations want to extend their international reach, the World Trade Organisation and the World Intellectual Property Organisation provide far more amenable – and effective - channels of coercion.

> Poster by Paavil, secondary school student from Uzbekistan, for the WSIS Poster Competition

> Poster by Paavil, secondary school student from Uzbekistan, for the WSIS Poster Competition

For all WSIS' shortcomings, however, there were dissenting voices. Communication Rights for the Information Society (CRIS) was established as a campaign group to press for information and human rights to be put at the centre of the summit's agenda.

CRIS organised a one-day conference on the summit fringes to raise issues such as surveillance, control and intellectual property reform. Sean O Shiocru of CRIS sees these issues as integral components of the market-driven dogma that currently defines technology development.

'The paradigm in telecommunications of liberalisation and so on has reached its limits,' he says. 'We need to get new paradigms for development so that people can develop their own services.'

For O Shiocru, part of the problem was the UN's decision to allow the International Telecommunications Union (ITU) to organise the summit. The ITU is the UN agency that regulates telecoms standards, such as international phone codes and radio frequencies – it is essentially a technical body.

'The fact that WSIS was run by the ITU meant that it had a very narrow conception of the information society,' he says. That conception can be reduced to two central objectives; the launch of a 'digital solidarity fund' that could finance huge telecom infrastructure projects in the developing world and to challenge ICANN's control over internet governance.

For the poorer nations prominent at WSIS, however, ITU was talking their language. For many, internet governance is a national security issue – after all, ICANN is an agency of the US Department of Commerce, so the US government could theoretically switch off any country's internet access.

But, by the end of the summit, it was clear that WSIS had achieved predictably little. The Digital Solidarity Fund was launched with a sum total of one million dollars - the largest donor being Senegal.

And WSIS failed to make much headway on reform of internet governance. After heated discussions with the US delegation, a committee agreed to commission a study on the issue and report back to the second leg of the summit in 2005.

Building a genuine information society that addresses the yawning chasm between the information-rich and the rest will take much more than a few summits. It is possible to address these issues with patient building of networks from the ground up using affordable technology and open standards. But WSIS suggests that, if technology development is going anywhere at all, it's in the opposite direction.

Offical WSIS website http://www.itu.int/wsis

Human Rights in China http://www.hrichina.org

Human Rights Watch – Yahoo! risks abusing rights in Chinahttp://hrw.org/press/2002/08/yahoo080902.htm

Reporters without Borders reports on:China http://www.rsf.org/article.php3?id_article=7237 Tunisia http://www.rsf.org/article.php3?id_article=7271&Valider=OK

Communication Rights in the Information Society http://www.crisinfo.org

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com