Sound Changes Sense

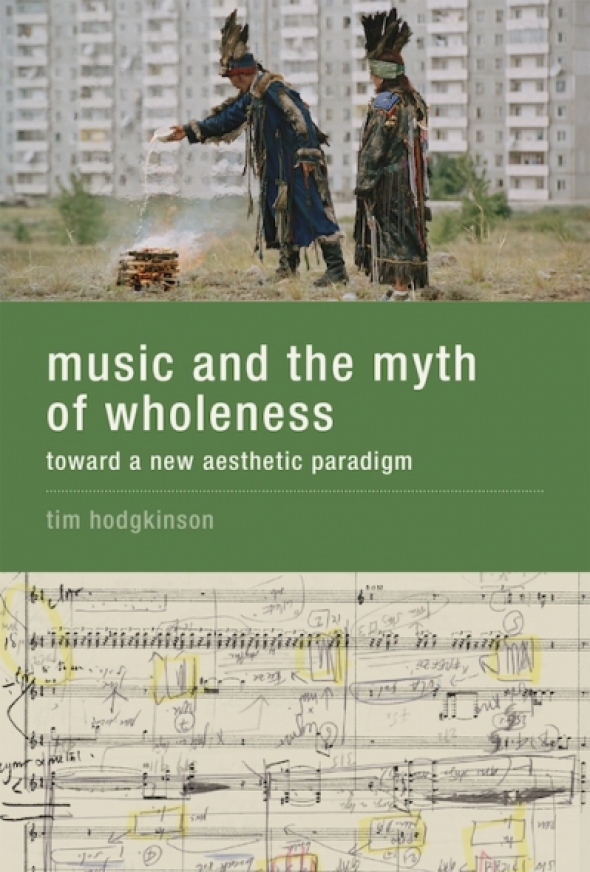

In his exploration of the power of music and sonority to reveal forbidden zones of being, Tim Hodgkinson’s aesthetic thought suggests ways to connect with the micro-politics of Félix Guattari. Here, Howard Slater travels to the nether zones opened by Hodgkinson’s recent book Music and the Myth of Wholeness – Toward a New Aesthetic Paradigm

‘Musical experiences … bring a glow to the

background hum of unaccessed memory’

– Tim Hodgkinson

In order to get a handle on this book for the purposes of a review, I began to draw up a diagram with the aim of arriving at a thematic overview that would slot together nicely and figure as a plan for the review. I went back through the book and pencil markings shot up at me from every page and I added these to the diagram. The A4 paper soon began to fill up with black ink and multiple lines drawn in pencil linking words and phrases together. With almost an air of defeat I noticed that the spaces of white on the sheet were gradually lessening and I was only half way through going back over the book! As usual my seeking out of a general thematic thrust, of a synoptic overview of the whole book, seemed either to disintegrate before a desire to follow tangents or, the same thing, begin grouping points of intersection between Hodgkinson’s book and the vocabularies of my own research interests. These were many: music as a non-discursive political force, the production of the subject, the group or ensemble setting as a means to pursue the relational impact of these. So, this preamble is as good as saying Hodgkinson’s book is a rich and provocative work on music and ontology, aesthetics and becoming, that draws upon an interweaving theoretical apparatus that took me out of my Freudo-Marxist comfort zone. Of the disciplines that Hodgkinson traverses and brings close to mutation and mutilation we could mention theoretical biology, cybernetics and information theory, ethnomusicology, anthropology, phenomenology, cognitive psychology etc.

Stated coldly like this such a list of disciplines would not prepare the reader for the way Hodgkinson tirelessly engages these disciplines to draw critical attention to and undermine the ways in which our culture’s self-definition, its logo-centricity, applies a categorical embargo upon us all. From what he calls ‘the myth of wholeness’, to the sense of music’s ontological impact as a ‘social force’, a key element of this book (or one I can ride along on enough to write about) is the way Hodgkinson is keen to tackle how subjectivity is produced according to what he terms ‘socio-logic’. One could suggest that this logic, with its functional and overly literal relation to making-meaning, is indicative of a capitalistic culture that rigidifies praxis in objectified structures and leads to a ‘repeated modelling of experience’ through which we introject an arrived-at sense of the self as whole and complete.[1] In a linked fashion, such a culture, whilst congratulating itself on what it knows, in fact rejects much that, using other enunciative means, could pass as knowledge – relegating it to nether zones. For Hodgkinson, this ‘social logic’, this drive towards institutionalisation (of culture, of politics, of music), is, in its enshrinement of a discursive functionality and a heteronomy of meaning, a prime means by which our powers of perception are reduced. Maybe these powers are encouraged to be reduced in the interests of a smooth accumulation of value for, as Hodgkinson seems to imply, a recursive form of perception (something akin to Deleuze & Guattari’s ‘desiring-perception’) can, at its widest, be furnished by the notional motion and generative dynamics of those estranging musics that tend to throw the smoothly functional yet brittle rhythms of socio-logic into a de-familiarising stutter.

That this book has a focus on ontology and music, or more specifically, is intent on bringing to light how subjectivities can be produced under the contextual conditions of listening to music and sound, is of keen interest in that it sets out from a basis in what could be called the reduced ontological possibilities of the subject produced under what Sylvia Wynter refers to as the bourgeois ‘classarchy of capitalism’. For Hodgkinson, one of the elements of this reduced ontology is what he calls the ‘myth of wholeness’. Writing in a direct fashion, he frames this as our tending ‘not to think of a single body as being occupied by more than one self. The notion of the subject is, however, more flexible’ [2]. As part of this flexibility Hodgkinson, for the purposes of this book, outlines a ‘locutionary subject’, a ‘sintonic subject’, an ‘oneirc subject’ and an ‘aesthetic subject’. We shall return to these, but, in line with Hodgkinson’s embracing of these differing subject-notions as not ‘wholes’ in themselves but phases and aspects of a subject’s multiplicity, we sense the presence of music and sound in defiance of a socio-logic that promotes the sense of self as a consistent ‘whole’ and not, as Hodgkinson offers, the human being as a ‘dynamic field in which different forces collide.’[3](. This description, framed as a query against the traps of a ‘wholeness’ that not only reduce possible perception but, in turn, suffocate the human with a sense of sensual boundedness between one and another ‘identity-position’, leads Hodgkinson to consider how, amidst this collision of forces that are difficult to articulate, we are an ‘embodied intelligence of immediate sensation.’ This latter is one means of approaching what Hodgkinson calls the sintonic subject; a kind of ‘tuning of sensory processes with the environment’, that could, as Hodgkinson shows, be aligned to descriptions of both shamanic séances and contemporary improvisation. Furthermore, the sense of an ‘embodied intelligence’, a bodily basis for (musical) thought, increases the sense of the subject as a synthesizing multiplicity rather than as an incompossible cohesive unit. This latter puts me in mind of a quote from Bergson about music. Something to the effect of ‘when we listen to music we are, in that moment, what it expresses’, we live it, as Sylvia Wynter once suggested of Carnival participants.

This ‘embodied intelligence’, given propulsion in the way that Hodgkinson raps on Pauline Oliveros’ notion of ‘deep listening’, is again, a bit of an outrage for a socio-logic that is heavily reliant on ‘language based representations.’ The praxis of listening (often subordinated to looking and appearing) is, Hodgkinson offers, a way to ‘relax from language.’ This seemingly simple statement belies a whole complexity that Hodgkinson uncovers in what could be called a ‘critique of language’[4]. Whilst not unrealistically defaming the ‘locutionary subject’, Hodgkinson draws attention to several aspects of our reliance on language that, rather than enhance communication and invent new forms for relatedness, go a long way to debilitating it and, as with those knowledges deemed superfluous, are creative of an excluded surplus of expression that has no place to go. To choose just one of these critical moments, Hodgkinson comments of language that ‘belonging to community and belonging to language become one thing. On the formal level, the discourse of each human group rigidifies itself against time – the medium of continuousness and indeterminacy.’[5] This warding off of the alterity of time, our remaining tightly held to a ‘serial time scheme’, debilitates not just experience of the ‘xenochrony’ of living history, but delimits psychological space and thus hinders our perceptive abilities in that we don’t have the language to describe ‘embodied intelligence’ (which is inclusive of the self-as-a-collective) or the almost imperceptible ways in which we undergo transformative processes of both interpellation and becoming.

If the ‘locutionary subject’ can be governed and made tight by the ‘discursive rules of a culture’s self definition’, then, the ‘oneiric subject’, a subject embraced in the West by the surrealist and psychoanalytical movements, offers a further means to relax from language. This leads Hodgkinson to an examination of ritual and, over many compelling pages, he recounts his experiences with the music and sacred rites of Siberian shamen. The dream component here is seen in light of the ways in which the Tuvan musician-shamen bring their ‘dream activity into social action’ in a way that provokes me into wondering how the surrealist ‘sleeping fits’ would have translated in settings other than André Breton’s flat. What comes to light in this sequence of the book treads ground that would cause many a materialist to seek a route back to logical philosophy, for the dream experiences of the ‘oneiric subject’ are linked to ideas about a ‘pre-discursive’ and ‘pre-social’ humanity. This is done in ways that not only give an indication of the historical breadth of this book, but which enable a relaxing from that tendency of language to make our attempts at relationality subject to an affectless ‘informational compartmentalization’. As the psychoanalysts discovered (not without help from centuries of music and poetry), the dreaming subject is not commandeered by the ‘serial time scheme’ and sense of ‘wholeness’ that afflicts us in waking life, neither is he or she wholly in the thrall of the ongoing flow of a ‘narrative self’ that often reflects and suffers from an ego-ideal imposed upon us by ‘socio-logic’. The ‘oneiric subject’, then, is more subject to an associational poiesis (a component factor in shamanic ritual as described by Hodgkinson) which of course leads further into undermining the sense of self as a ‘whole’ whilst pointing firmly in the direction of ritually-held dissociational states (nether zones) that threaten or entice us with ‘indeterminate psychical behaviours’ which, when permitted a voice and a space of expression, carry an ontological dynamism[6].

Some may, by now, be remarking upon the absence of music in this review and rightly so as discussions of music, from Albert Ayler to Anton Webern, abound in this book. These remarks, then, have me running back to the half-finished diagram to furnish examples at which point I also discover that I have made no mention of Tim Hodgkinson as a multi-instrumentalist, improviser and composer who began a public life in music with Chris Cutler and Fred Frith in the Henry Cow. But not only is this review unfinished and not a little indeterminate, it is composing itself as it goes along and, by finding a form or a spine for this review in Hodgkinson’s quartet of subject positions, my confidence has risen during this performance and I feel ready to embrace this seeming omission and bring it round into a factor that adds to my fascination with this book as a research tool for the proposition that music as an ontological intensity and relational praxis can refound politics. If I have not mentioned music (except for the Siberian shamen) then this is a result of my indebtedness to Deleuze & Guattari’s notion of the ‘non sonorous forces’ that are unleashed by music. So, Hodgkinson’s lifelong reflexive experience as a musician is at the bedrock of his book, which as a non-sonorous force in itself, has arisen from a deep listening that brings forth from musical material many of the musings being pursued in this review.

When, very early in the book, Hodgkinson writes of musical experience having resonances that extend well outside such experience, he is, I think, talking of music in its guise of prompting non-sonorous forces. We have already been drawn into seeing how our experiences of music have instigated a critical distance from an untroubled use of language, how music’s simultaneity and polyphony provide a grounding for a sense of ‘self’ as a componential multiplicity rather than a ‘whole’ and narratively coherent subject. To these could be added another key non-sonorous force that Hodgkinson returns to many times in this book and which, for this reviewer figures as a kind of keystone to its underlying theme of music and ontology. This, then, is Hodgkinson’s insistence upon the ‘intrinsic non-finality of perceptual representations’ that, emanating from deep listening, instigate a sense of a ‘continuous receptivity of perception with itself as it goes ahead.’[7] Drawing upon a praxis of listening which he convincingly articulates as non-passive, performative and an amplifier of embodied pre-verbal knowledge, Hodgkinson seems to be suggesting that this perceptual flow figures the subject as always ‘coming into being’ as a dynamic field that is recursively phasic rather than accumulative. That we have our own histories of perception (c.f. repeated listenings) is not only a factor informing the interrelationality of our multiplicities, but it can enhance the levels through which we can communicate. As Hodgkinson states: ‘The loss deferred in the real negotiation between language and perception is not now deferred but assumed’, and it is just such an assumption of the pre-verbal areas of our experience (linked to the ‘non-verbal perception’ of music and sound) that can form the basis of a renewed desire to speak otherwise.[8]

In contrasting such a ‘desiring perception’ with the socio-logical inference of a ‘one-off all encompassing act of perception’ we can suggest, through Hodgkinson, that not only is this one-off act encouraged by the time-constrained commodity forms which music is often led to take, but that there is pressure placed on us by socio-logic to ‘perceive all there is to perceive’ in this one-act (later Hodgkinson will talk of the ‘burden of consequentiality’ that comes along with this too). That these induce anxiety (which is itself a form of discarded knowledge fit only for the nether zone) is one reason why more estranging musics are often reacted to so disparagingly. Hodgkinson (who saves his discussion of the musics of John Cage, Pierre Schaeffer and Helmut Lachenmann to the penultimate chapter), offers another insight into this anxiety when he writes: ‘For the nonfinality of perception to become more than merely potential, a distance must open up between perceptual images and […] an automatic recourse to interpretative schemas…’[9] That these automatic recourses are, it could be offered, the very responses that go towards forming a self-protective barrier against having socio-logic appear to us as dysfunctional, it is the knee-jerk recourse to ‘interpretative schemas’ that can make us deaf to all but the sound of our own anxiety (injunction of a ‘logical’ inner voice). Giving us a sense of what is to come in the penultimate chapter, Hodgkinson continues: ‘Objects deliberately designed to encourage nonfinal perception may be reacting against a semiotic form of perception overeager to dissolve sensible experience into meaning.’[10]

Before we approach the nether zones that temporarily house both excluded knowledge and nonfinal perception and, with these, take up Hodgkinson’s ‘nonfinal objects’ as having the ‘quality of a relational configuration’, it should be added that this lust for a language-centric meaning has the ontological drawback not only of inculcating means of subjectification that are underwritten by the finality of categorical definition but, as Hodgknison, in terming the socio-logical as a cultural ideology, points out: ‘This ideology cannot in its own terms, deal with one thing becoming another, with transition between categories: on the contrary, transition becomes the occasion of a discursive crisis.’[11] What D.W. Winnicott has, in the therapeutic context, termed transitional spaces and transitional objects can well apply to the way that music, (maybe more so) estranging musics, can hold a many-faceted subject in an uncompleted liminal space that avoids overeager interpretation (a byword for disaster in therapeutic praxis) and, helps to introduce and legitimise the very existence of a componential self. As Hodgkinson suggests, the repetition of listenings (or, analogously, the repetition of the form of the therapeutic hour) is not a return to the self-same of socio-logic, but a modulating perceptual experience, that, in loosening the bonds of language encourages ‘embodied intelligence’ and the ‘continuous work of the senses’ to receive a communicative boost outside of serial time pressures and their premature endings. Much estranging music is not instantly appreciated in an orgasmic fashion but, as with the social-self insights of therapy, much of the music discussed by Hodgkinson (from the metamorphosing flights of the Tuvan throat singers to the ‘relaxation of cause and effect’ in Schaeffer’s musique concrète) could be loosely said to encourage the ontological dynamism of desiring-perception by sounding out a liminal space between the known and the unknown and holding this sonorous space for the recursive introduction of the (often affective) detritus shed by the formulae of socio-logic.

I return from the book. There is so much I am omitting to mention, but rather than pretend it’s not there I may as well mention it so as to entice potential readers at the same time as I can stage my own limits and remain free from being obligated to respond ‘wholly’ to every facet of the book. This isn’t a peer review’ after all. Maybe the parts I cannot understand are those more related to composing and how musical form can take shape as a paradigm of social relations (or did I just make that up?). Maybe I would answer with a ‘yes’ to Hodgkinson’s question: ‘Is it inherently reductive to speak of a society or of a culture as an informational field?’ Whilst I have enjoyed this approach as refreshingly other, maybe I sense that I am too schizzy and thus can access Hodgkinson’s listening self but, at times, fail to follow this self when it turns to compositional analysis. But, there is time. Time to return. Music makes time. So, here, rather than these commentative passages (without which I could not have begun) be seen as pseudo self-reflexive they are just as much a means to flaunt the socio-logic of institutional functionality whilst pointing to the ontological production that can be heard in improvisational openness. To paraphrase what Hodgkinson says of free collective improvisation: it is not what is that must be and remain so, but that whatever it is could be always otherwise.

Such a different channel for desiring-perception and its proto-meanings, a channel that is suggestive of what we do not hear (or what we could hear if we can find the communicative means offered by that which is cast out by socio-logic) is not only suggestive of the utopianism of l’imagination au pouvoir, but is similarly linked to what I am calling nether zones and Hodgkinson calls ‘dynamical ontological environments’ through which space and time are found for excluded knowledge, for the liminalities of nonfinal perception and for speaking and sounding otherwise. For Hodgkinson these nether zones are the ‘free cognitive spaces’ of the aesthetic and ritual realms: ‘Whereas functional domains provide perceptual closure and the point where objects are linked to their use values, the aesthetic domain extends perceptual space upwards.’[12] Whilst much of Hodgkinson’s discussion of the aesthetic carries with it a forceful deconditioning import[13] that reminds us that his book has a very similar title to Felix Guattari’s Chaosmosis: An Ethico-Aesthetic Paradigm, one begins to wonder whether, for Hodgkinson, the liberatory aim of the ‘self production of subjectivity’[14] is less in the direction of a collective becoming for all (an ontologised revolt currently being refreshed as ‘decoloniality’), and more being led upwards towards further enshrining the perceptual delicacies of an aesthetic subject. Whilst a comment such as this may be a way to further enshrine an unadventurous leftism, it may well be that, in the absence of a necessary epistemological collapse with its loosening of fixed meaning and removal of expressive injunctions, we still have to seek generous translatory flows between the still extant categories of the ‘aesthetical’ and ‘political’ which may be another way of once more saying ‘micro-politics’.

A factor that could encourage such a generosity is that both Hodgkinson and Guattari have an approach to the aesthetic that could be more aligned to what Marx calls ‘species-activity’ and which Wynter, glossing C.L.R. James, refers to as the ‘genus homo of the free-play of faculties’. Both of these writers are urgently concerned with a praxis of art making as process-based, open-ended, deconditional, acategorical and ontologically transformative.[15] Whereas some critics of Guattari may say he veers towards a boundless and hermetic schizophrenia it could be noted that Hodgkinson, in stressing art’s autonomy from meaning, could also be interpreted too tightly when he offers that as aesthetic subjects we can be addressed from ‘outside society’.[16] Maybe I’d rather he have said from ‘outside socio-logic’ but maybe this too is just an impossible utopian dream unless we take the abject sincerity of an Artaud to heart or listen intently to the Afro-Pessimists as they talk of black people undergoing ‘social death’. Both of these examples trouble the meaning of being together which itself feeds into the problem of sustaining collectivities as ‘ontologically dynamic’ outside of the prophylactic temptations of essentialising identities and perceptual alignment. This points to a further (micro) political problem raised by Hodgkinson in that if ‘non-final perception’ is to become more than potentially galvanizing, it needs to overcome not just the lust for meaning and closure, but also what he describes, after Bakhtin, as the ‘irreducible singularity of the physical perceptual viewpoint of the individual.’[17] Such an irreducibility can imply more than just distance. It implies a clash of incompossibles in which the struggle to communicate by means of the socio-logics of language leads to exclusivity and marginalisation functioning as a means to foreclose that ‘irreducible singularity’.

So, with ‘non verbal perception’ being a mainstay of participating in the ontologising dimension of music making, it is time to be reminded that Hodgkinson has offered that these ‘non final objects of perception have the quality of a relational configuration’. Hodgkinson points out: ‘A person who is marginalized by a dominant discourse and its subject form is likely to be particularly open to other forms of subjectification, such as those offered in the experience of certain forms of music.’[18] Just as this points towards the huge counter-cultural contribution of music, it also points us in the direction of different forms of ‘relational configuration’ that can take place in the nether zones; configurations which, following the drive of this book, must be sonorously constituted by excluded and socially forbidden knowledges that, as transitional and liminal modes of experience, imply, for now, the necessity of communicating that ‘irreducible singularity’ in a non verbal form. The nether zones that Hodgkinson focuses on are those of ritual and (musical) aesthetics, but we could add to these counter cultural spaces (c.f. the Township Jazz of the ’60s and the reggae sound systems of the ’70s) and therapeutic spaces (c.f. the anti-psychiatric and therapeutic community initiatives). These too are spaces where ‘irreducible singularities’ rather than ‘artists’ or ‘therapists’ become the constitutive operators of the ‘relational configuration’ and that we ourselves can there, in the flow of tracks or in the flow of non-sense, become expressed as the ‘non final objects of perception’ for one another, as no longer ‘wholly’ incompossible.

The questions that come to be posed through this book seem, to me, to coincide with those that Guattari asks. Both want a refoundation of political practice. Hodgkinson: ‘How does an ontology of the aesthetic subject catalyze an ontology of the political subject?’[19] In some way Hodgkinson’s question is being continually answered throughout the book in the forms of his analyses of music and sound. It comes to settle, for this reader at least, in an ontological force made up from …

… desiring-perception

(fascination with the non-final object which is creative of an awareness

of subjectivity as both multiple and unfinished)

… non-sonorous forces

(‘music as a resource catalyzing the development and nurture of forms of corporeal organization and states of being’ )

… and a recursive sense of subjectivity

(‘All musical listening is reflective, and this reflection arises in music’s recursive process. Each musical instant elicits a retention and is therefore open to be changed retrospectively as it enters into relation with a new instant’) [20]

These are maybe the means through which an aesthetical subject, taking its impetus from immersed musical experience, can provoke into existence a political subject. But we must be cautious, not of enticing into existence a ‘new being’, but of realising that such a ‘new being’ is an ‘old being’ is a ‘collective being’ and so far has found little room to manoeuvre under the hegemonic sway of a politics conditioned by socio-logic. Just as for Guattari, Hodgkinson too is pointing towards a micro-politics: a politics that take cognisance of excluded knowledges, ‘uncounted capacities’ and their modes of expression that often seem irreducibly singular. Music, then, calls for a ‘refounding encounter’, not between individualities, but between subjects as multiplicities. The means for this refounding can be inspired by music. In discussing free collective improvisation Hodgkinson says that, in this context, in this nether zone, the ‘musicians are the formative other’ for each member of the ensemble.[21] We are not looking here at finding elbow room for instinctive solo space but at the modulation of forms of expression that drive and structure the musical form as it unfolds. As Sun Ra has said, without the need for Gilbert Simondon’s theory of collective individuation: ‘The expression of you in the interplay of the self and the alter self’. We can conjecture that for Ra the ‘alter self’ is an amplification of multiplicitous and approximate selves that socio-logic makes residual and consigns to one of many growing nether zones.

Howard Slater <howard.slater AT gmail.com> is a writer and researcher who lives in London

Tim Hodgkinson, Music and the Myth of Wholeness – Toward a New Aesthetic Paradigm, MIT Press, 2016

[1] In writing about C.L.R James’ Beyond a Boundary, Sylvia Wynter suggests that the extent of this ‘socio-logic’ with its ‘repeating modelling’ (what she calls, after Castoriadis, the social imaginaire) is its control over the ‘mode of identity and desire.’ See Sylvia Wynter ‘In Quest of Matthew Bondsman: Some Cultural Notes on the Jamesian Journey’ in Urgent Tasks No.12, 1981.

[2] Tim Hodgkinson, Music and the Myth of Wholeness: Toward a New Aesthetic Paradigm, MIT Press, 2016, p.38.

[3] Ibid., p.4.

[4] In discussing the ideas of Terrence Deacon on the symbolic and gestural origins of language (The Symbolic Species,, Penguin 1997) Hodgkinson offers that ‘there was pressure for agreement within human groups to represent the relationships inside the group in a durable way, unaffected by fluid situational realities and immediate contexts […] There would not have been words, but durable signs […] such as stones lodged in the crooks of trees.’ (p.64)

[5] Hodgkinson, op. cit., p.67.

[6] For Hodgkinson these ‘indeterminate psychical behaviours’, in being deemed lacking in ‘operational reality’ or outside the socio-logic of compartmentalization, come to be a driving force for the nether zones of ritual as these make a bridge towards the aesthetic. Both the ritual and aesthetic, Hodgkinson seems to be arguing, return ‘ontological value’ to that which is ‘inadmissible’. Often it feels like it is inadmissable to remain silent and just listen (to music): ‘People come to ritual because they sense that it temporarily breaks the nexus, the alienating knot, of the discursive self.’ (p.91)

[7] Ibid., p.101.

[8]Ibid., p.163.

[9] Ibid., p.41.

[10] I think here of the experience of attending to soundscapes or field recordings where, with the deliberate creation of a ‘listening continuum’, there is what Hodgkinson calls ‘sustained sensory engagement’ (p.174). Perhaps such a sustained engagement of the senses is a way to win back the control of ‘modes of desire’ from socio-logic?

[11] Ibid., p.83.

[12] Ibid., p.134.

[13] For instance, in referring to avant-garde art movements, Hodgkinson states, ‘In the modern period art communities and their traditions become less stable, and we see the extent to which a structure of knowledge defaults […] back to a generative ontology phrased in a dynamic of not knowing.’ (p.145) These musings can be brought into reference with the ‘telling inarticulacy’ that Nathaniel Mackey outlines as a feature of jazz and the SKANGA of black culture.

[14] Ibid., p.9.

[15] ‘The work of art, for those who use it, is an activity of unframing, of rupturing sense, of baroque proliferation or extreme impoverishment, which leads to a recreation and a reinvention of the subject itself.’ Felix Guattari, Chaosmosis: An Ethico-Aesthetic Paradigm, Power Publications, 1995, p131.

[16] Hodgkinson, op. cit., p.152.

[17] Ibid., p.31.

[18] Ibid., p.121.

[19] Guattari: ‘Art is not just the activity of established artists but of a whole subjective creativity… I simply want to stress that the aesthetic paradigm – the creation of mutant percepts and affects – has become the paradigm for every possible form of liberation…’. Op. cit., p.91.

[20] Whilst the work of Gilbert Simondon is briefly referenced by both Hodgkinson and Guattari, much of the micro-political drive that I’ve felt whilst reading this book can be pursued further through Simondon’s notion of collective individuation. This can briefly be described as the way that interaction between the components of our multiplicities is further ‘individuated’ (encouraged in its becoming) by belonging to ‘associated milieus’ whose ‘reality of relation’ constitutes a further operation of ‘individuation’. It is implied that the means for both individual and collective individuation is ‘the reserve of being from which everything becomes’. For me this ‘reserve’ can figure twice as both that which is excluded from socio-logic and that which through ‘inhibition’ cannot find a means of expression. See Muriel Combes, Gilbert Simondon and the Philosophy of the Transindividual, MIT Press 2012, p.65.

[21] Ibid., p.188.

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com