Reflections on the Arab Spring

Twittering teens or absolutist ayatollahs, men we can do business with or loony autocrats? The media’s proliferation of polarities is a strategy to fragment the connectedness of events and disavow western Realpolitik. Here, Anustup Basu reveals the transnational composition of a Spring that is now a Winter

In a column published on 25 May, 2011, The New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman issued a pious call to Palestinians. In the wake of the Arab Spring, he invited them to learn from the Egyptian insurrection and adopt the ‘Tahrir Square Alternative’ (TSA). That is, to announce every Friday a ‘Peace Day’ and march, in thousands, to Jerusalem, holding an olive branch and a plea for Palestinian statehood, written in Arabic as well as Hebrew, just to avoid any tragic misunderstanding. Implicit in Friedman’s conscientious liberalism is a desire for a game-changing symbolic event, one that would insert itself into the sea of information about the uprisings and bring to the fore the image of the peace loving Palestinian finally cleansed of the stigma of pathological fundamentalism attributed to formations like Hamas. The TSA would thus be a transformational strategy that would not just win the hearts and minds of Israel and the world at large but also ‘surprise’ Benjamin Netanyahu, who, in Friedman’s self-admittedly ‘crazy’ universe, sits in some future anterior moment, reading the column and laughing with characteristic cynicism: ‘The Palestinians will never do that. They could never get Hamas to adopt nonviolence. It’s not who the Palestinians are.’1 Friedman of course did not clarify whether the ‘surprise’, for ‘Bibi’ would be a pleasant or an unpleasant one.

Secondly, Friedman, in his ardent paternalism, assumes or gratuitously pretends that said strategy has not been already thought of and tried by the Palestinians themselves, including those in Gaza who currently reside in what could well be the largest open air prison in human history. Peter Hart, writing for FAIR (Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting), has pointed out to Friedman that as a matter of fact Palestinians have, and have for a long time, relentlessly practised the non-violent option without managing to ‘surprise’ Netanyahu. Such efforts have largely been met with swift and uncompromising repression; they have been responded to with tough love, in the form of arrests and detentions, stun grenades, tear gas, and gunfire.2 As a 2005 study by Patrick O’Connor established, Palestinian non-violent movements have been overwhelmingly ignored by the free press of the western world.3 The onus is thus perpetually on the Palestinians, no matter what they do, to emerge – with agon, sacrifice, and endurance beyond human finitudes – as a people capable of some form of newsworthiness that has nothing to do with suicide bombings or crude Qassam rockets.4 Friedman’s invitation towards peace and non-violence emerges from a powerful theme of mainstream American and Zionist common sense that is already weaponised: that Palestinians specifically, and Arabs in general, by virtue of their existence, pose an existentialist threat to Israel and that all their actions, hitherto, have been met by Israel with the solemn purpose of defending itself, no matter what the undertaker says.

The current scenario in Gaza is one of a grotesque human catastrophe perpetrated in slow motion.5 It is the outcome of a half a decade long vice like embargo and mayhems like the IDF’s Operation Cast Lead that, between 27 December 2008t and 21 January 2009, left about 1,400 Palestinians dead and countless injured. And yet, it is this beleaguered 1.5 million strong slice of humanity – plagued by crippling poverty, disease, toxic water, shortage of food and medicine, absence of basic infrastructure and acute unemployment – that seems relentlessly to threaten not just border security, but the very existence of Israel itself. There can therefore be no authentic freedom or exercise of democracy for them without that either bolstering American-Israeli interests or keeping the existent status-quo.6 As a matter of fact, it seems that there can actually be no recognisable ‘people’ or territorial notion of ‘home’ unless these conditions are met. The Death Laboratory of Gaza was a geo-political creation of Israel itself, when Ariel Sharon ‘disengaged’, removing Israeli citizens and settlements from that space in 2005. With it left the last vestiges of imperially recognised ‘peopleness’ from that space, one that could be attached to humane concerns about peace, neighbourliness or hospitality. It was that strategic withdrawal that created the possibility of reinventing Gaza as a pure ground zero of ‘bare life’, as Georgio Agamben would say, where, following a long standing Zionist theme articulated by Golda Meir and many others, the Palestinian people (or for that matter any people) do not exist. What exists is a pathological biomass, an absolute spectre of Islamic terror that needs to be defended against, with the old, infirm and infantile to be dubbed ‘human shields’. It is this weaponised and mediatised defensive redoubt that holds paramount status, especially when it comes to territories illegally occupied by Israel from the West Bank to the Golan Heights.7

The Spring of the Present and the Long Hot Summer Otherwise

I have begun this essay with this grotesque picture from the recent past for three primary reasons. The first one should be fairly evident – that American mainstream media responses (which I will largely focus on) to events like the Arab Spring are guided by a curious mixture of an almost onto-theological commitment to abstract, totemic ideals like ‘freedom’ and ‘democracy’ and a Realpolitik one to American strategic, monetarist and security interests in the Middle East. In the overall flow of informatised commonsense, the two lines of reckoning are rendered inseparable. Democratic structures of representation anywhere in the world cannot be disruptive in relation to networks of governance and financialisation stipulated by the Washington Consensus. Democracy must yield ‘liberalism’ in its neo-incarnation; it cannot give us Hamas or the Muslim Brotherhood, instead. My second reason is that the ‘Arab Spring’ is still unfolding in front of us with a long rumble. It is always difficult and dangerous to ‘read’ the present, for any understanding of it is already belated. The present has to be grasped in a manner that is open to the many imaginative and political possibilities – of self-making, sovereignty or antagonism – that it brings. My invocation of the Israeli-Palestinian situation has been intended to illustrate a habit of neoliberal statist thinking that, in the name of security, stability and combatting terror, threatens to kill us, anyway. It is this murderous habit of thinking that imperils, more than anything else, the exhilarating possibilities of the Arab Spring.

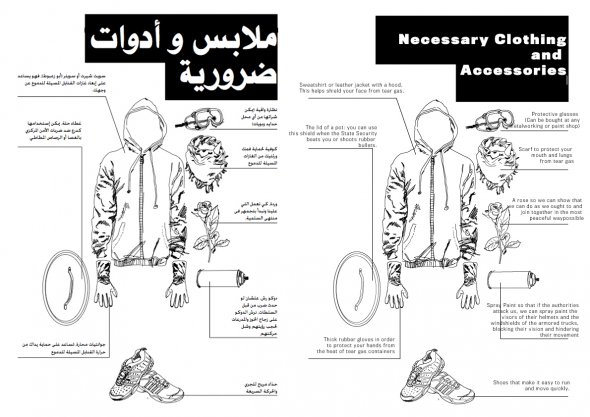

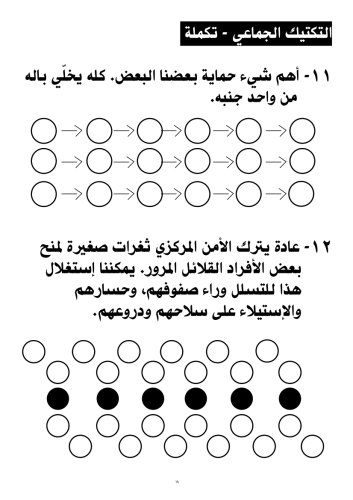

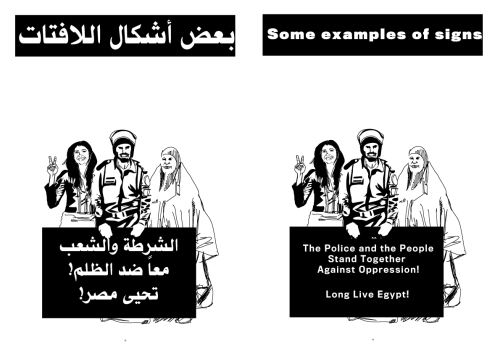

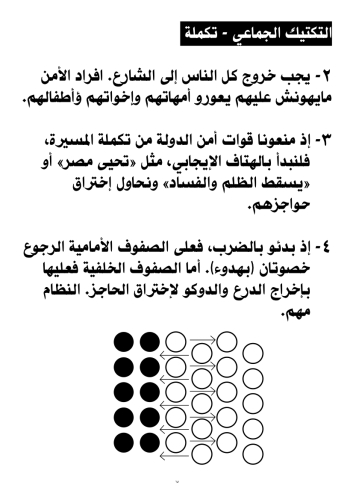

All images: from the Anonymous pamphlet How to Protest Intelligently, c.2010-2011

The third reason pertains to an obvious paradox: unlike the Egyptian or Iranian youngster who apparently just wants to be an American teenager and tweet in peace (much like the American who waited to jump out of every Gook in Vietnam, according to the emphatic Colonel in Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket), non-violent democratic activists in Gaza somehow have not been able to twitter themselves into the spotlight. Curiously, neither have democratic activists brutalised and jailed in countries occupied by the United States or its allies: Yemen, Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, Sulemaniyah Iraq, Afghanistan or the United Arab Emirates. Media focus on popular outrage expressed on Twitter or Facebook seems to be disproportionately trained on enemies of the West, like Iran, Syria or Libya. It is not that there were simply no tweets from Bahrain when Saudi and UAE forces, armed with their latest military acquisitions from America, marched in to crush the insurrection; it is just that such voices were not deemed ‘newsworthy’. That is, they were evaluated as such when ‘news’ itself in our informational world, as the late Derrida astutely observed, is that in which ‘actuality’ tends to be ‘spontaneously ethnocentric.’8 It is this instantly consumable, informatic and industrialised ethnocentrism that encompasses not just state policy, but also a media space dominated overwhelmingly by about half a dozen giant conglomerates devoted to global metropolitan interests.

This is not to say that in a world of horizontal connectivities other voices, evocative images of alterity or testimonies of anguish or pain are not registered and shared across the world. The point, however, is that increasingly, in our occasion, statist dominance over the media ecology is exercised not so much in axiomatic, top-down ways through censorship and elimination (although some such efforts exist: George Bush bombed the Al Jazeera offices in Afghanistan in 2001; Ben Ali banned YouTube, dailymotion and Takriz; Mubarak shut off the internet and cell phones; China, at one point, prevented recent images of insurrection entering its media space). Instead, dominance is achieved by absorbing errant images and sounds to already-there, massified structures of feeling and perception: orientalism, race, terror, security, stability, Islamophobia, pious concerns of Clintonian multiculturalism or anxieties about immigrants. The point, therefore, is not to shut out, in a total manner, images of disturbance, but to absorb them as fresh noises into an overall clamour already enveloped and dominated by axiomatic myths about free market and freedom and about America being the reluctant behemoth of good in a dangerous world. This is how questions of human dignity and liberty become tied to a presiding onto-theology of capital. This is also how relations around Egyptian youth protests are enframed and tempered by the Realpolitik fear and loathing of insidious energies hailing from that nebulous thing called the ‘Arab Street’. Ergo, it is to be lauded that the former want democracy, but with the latter around, perhaps, that might be too soon.

It is this already techno-deterministic template of information culture that encourages one unquestioningly to distinguish between greater evils and ‘practical’, ‘indispensable’ ones, between rhetoric of necessary change and a metropolitan strategic silence in which all of us are invited to be complicit. Bahrain has been ruled by the Sunni Khalifa dynasty for well more than two centuries now. If the world was to turn upside down and the hitherto repressed Shia majority were to gain political prominence, Bahrain, as per a realist-statist world view, would inevitably tilt in the direction of Iran. That would not bode well for the greater cause of freedom in the world since Bahrain houses the US navy’s fifth fleet and is strategically important for the control of the Suez Canal and the Straits of Hormuz through which almost a quarter of the oil supply passes. Similarly, despite the fact that President Ali Abdullah Saleh has ruled Yemen for 33 years and has had untrustworthy flirtations and friendships with Russia, Iran and Saddam’s Iraq, his brutal efforts to strike down dissent in his country did not attract as strong condemnations as did Assad’s in Syria. While the Obama administration and the Gulf Cooperation Council Bloc has pressurised Saleh – presently convalescing in Saudi Arabia after an assassination attempt in early June – to step down and allow the Yemeni people to fulfill their ‘aspirations’, it remains amply clear that the broader template of regional ‘cooperation’ cannot allow such aspirations to disturb American military interests in this impoverished Arab country due to its location near the major waterways and Somalia. Saleh has been a faithful soldier in the ‘War on Terror’; he has allowed the Obama administration to open – along with Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan and Libya – a fifth theatre of conflict in Yemen in which there have been repeated drone attacks to kill the few hundred members which al Qaida in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) supposedly has.

In contrast, the ‘Arab Spring’ has provided a wonderful opportunity for the West to topple Muammar Gaddafi in Libya*; until recently this eccentric tyrant must have been envisioned as a sobered up version of his cold war self, for he was deemed trustworthy enough to be granted weapons worth $470 million by the European powers in 2009 alone. For its part, before the calls for change became strident, the US government was working on a weapons deal worth $77 million just to top off the $17 million it provided in 2009 and the $46 million it supplied in 2008.9 Perhaps too much eccentricity or too much tyranny is not how Gaddafi overplayed his cards. Perhaps he has come to regret the statement he made in January 2009, expressing a desire to nationalise the Libyan oil industry.10

Friedman’s pious articulation of the TSA, of course, does not take into account either the fact that the United States and North Atlantic powers have been supporting dictatorial or authoritarian regimes in Cameroon (Paul Biya), Turkmenistan (Berdimuhamedow), Equatorial Guinea (Nguema), Chad (Idriss Deby), Uzbekistan (Karimov) or Ethiopia (Zenawi), apart from the usual suspects in the Gulf, or that it has also been providing many of these regimes the arsenal to prevent or exterminate the TSA. Perhaps it slipped Friedman’s mind that the Arms Industries of the West (dominated overwhelmingly by the United States) have been consistently supplying these regimes with weaponry that has been used not against foreign threat, but almost totally to keep domestic populations in check. It is the West that has been giving them ‘deep packet inspection’ technologies through firms like Narus, Ixia or Sandvine to police the airwaves and throttle dissent and subversion. Hence it was not just the ‘Made in USA’ tear gas canisters used in Tahrir and dolefully pondered over by talking heads in mainstream American media, but also the live ammunition, armoured cars, helicopters and tanks used to crush the TSA in the Pearl Square in Manama, Bahrain. In this case, it was not just the people gathered to protest, but the Square itself that was eliminated.

The Logic of Telelocalisation: What is so ‘Arab’ about the Spring?

From discourses of governance that abound in print and electronic media, it has become apparent that a new Egyptian dispensation has to prove that it is capable of handling ‘freedom’ and ‘democracy’ responsibly by sticking to some essential things: continuing to be a client state of American-Israeli interests, maintaining the Camp David accords and aiding in the blockade of Gaza11; keeping the Suez Canal accessible to western powers and closed to Iran; securing the crucial pipeline that supplies natural gas to Israel and other Arab nations. When Mubarak closed the Rafah Crossing more than three years ago to strengthen the deadly embargo on Gaza, it was a deeply unpopular move in Egypt. It is expected that his successor will continue to do such things no matter what the ‘people’ say. The ‘revolution’ is thus expected to shrink and step back into an already awaiting straitjacket of ‘responsible reform’, one that will keep certain planetary structures of financialisation and war in place. It is, therefore, ‘telelocalised’ from the onset as a local rumble that must eventually be diagnosed, bracketed off and absorbed into the great administration of things. The Egyptians, for instance, could warily look southwards and recall the grotesque overwriting of Nelson Mandela and the African National Congress’ Freedom Charter by powerful western financial institutions after the end of apartheid.12 They could also remind themselves that fresh updated versions of the neoliberal ‘shock doctrines’ are usually tried out first in the peripheries rather than in the metropolitan centres. Statist neoliberalism, as a matter of fact, was first tried out in Pinochet’s Chile after the coup d’état in 1973, more than half a decade before it became the template in Thatcher’s England or Reagan’s America.13 There are strong indications that something similar is presently being attempted in Iraq.

As per a panoptic point of view of neoliberal governance, all forms of self-making, desire and hurly-burly of protest must finally yield to the civic religiosity of North Atlantic market structures. Ronald Judy has identified this planetary form of sovereignty as that which is ‘the realization of perpetual change and a pre-emption of change at the same time.’14 The only firmament of transformation that is thereby allowed is that of the ‘free market’. Apart from American-Israeli geopolitical interests (and their bywords for these like ‘security’, ‘stability’, etc.): ‘responsible freedom’ also means following some already awaiting imperatives of military-industrial finance: the proper handling of the annual three billion dollar US military aid to Egypt and continued issuance of lucrative arms contracts to Lockheed-Martin, Boeing, General Dynamics or Raytheon.

It was in this spirit that the western powers, encouraged by Mossad, first called upon Hosni Mubarak himself to be the midwife of ‘change’ and, failing that, attempted to put Omar Suleiman in his place. Having headed the Egyptian General Intelligence Service (EGIS) since 1993, Suleiman was not just instrumental in choking dissent among his own countrymen, but also the chief supervisor of ‘extraordinary rendition’ programmes that the CIA delegated to him.15 That, too, failed and the scenario, under military control, is still an unfolding one. However, it can safely be said that the Egyptian people can expect many such a tip of the hat. Quite a few of them, as Karl Marx observed in a different, but exemplary context more than 160 years ago, will be that of the Napoleonic three-cornered one.16 For the moment, apart from the geo-strategic concerns already mentioned, the West will be watching with avid interest how, in the new dispensation, the Egyptian economy will be structured, given that the entity in power, the Egyptian armed forces – the beneficiary of more than 40 billion dollars from Washington since 1979 – virtually dominates all its sectors.17 The International Monetary Fund has already granted a loan of $3 billion to the interim government, after consistently praising the elite kleptocracy headed by Mubarak over the years for pushing through neoliberal measures and devastating the Egyptian population.18 There are also growing concerns about the future of labour rights, press freedom and the rights of women and minorities in the new dispensation of ‘stabilisation’ and ‘modernisation’ that is coming into being.

We have long since pondered whether the revolution will be televised; it is only lately we have started wondering about what it means for a revolution to be ‘informatised’. The latter is a relatively new architecture of power in our times; it entails a managing of popular energies and worldly humanitarian and political concerns by ascribing a human face to ‘change’, giving a proper name to Mephistopheles (Ben Ali, Mubarak, Saleh, or Assad) as well as the Messiah (Mohammad ElBaradei or perhaps Google’s Wael Ghonim) and then restoring the catastrophic balance of imperial interests. Cranky old patriarchs can have their Autumns; people can have their Springs; iron death masks of power are eminently expendable or changeable beyond a point; but the planetary military-industrial-techno-financial assemblage is not. The power of informatisation seeks to ‘telelocalise’ a milieu of unrest from an almighty metropolitan perspective; it seeks to invent the ‘people’ as well as manage, dictate and name its ‘aspirations’.19 This it does by polarising themes (Egypt contra Iran, twittering teens contra absolutist ayatollahs) or collapsing them together (Muslim Brotherhood plus al Qaida plus Taliban); making instant and vulgar comparativist evaluations (a ‘secular’ tyranny is a lesser evil than Islam/Terror); and curtailing the historical horizons of possibility by drumming transcendent abstractions like ‘security,’ ‘order’ and ‘stability’.

The social power of informatisation draws its powers from a mythical, cosmic perspective it has claimed for itself. It is from these commanding heights that it ‘invents’ and represents a ‘locale’. It is necessary to ‘represent’ something because, unless something is represented, it cannot be governed. Consider the statement made by Tony Blair in January, 2011 on BBC Radio 4, distinguishing between Mubarak and Saddam Hussein: he said that the two cannot be called comparable dictators because Mubarak has presided over an ‘Egyptian economy’ that has doubled in the last decade or so.20 That factor, along with Mubarak’s strong military support for western interests beginning with the first Gulf War, makes Egypt a theatre in which only the logic of economism and that of the ‘War on Terror’ need apply. In this majestic abstraction of Egypt in relation to world affairs, it becomes a matter of very small print that, officially, more than 22 percent of the population live in abject poverty (less than $2 a day), with an equal number very close to it; that the rate of unemployment is close to 10 percent and more than double that amongst the youth; and that common people, in recent years, have been hit by an inflation in consumer prices that perpetually hovers close to 12 percent.21 Like in many similar scenarios, these official statistics do not account for the current global malaise of underemployment. Shortly before the eruption of the ‘Spring’, there were demonstrations in Egypt calling for a monthly minimum wage of 1,200 Egyptian pounds; the kleptocratic government full of businessmen could promise only 400 LE, which amounts to about $67.22 Blair’s sweeping statement, in a figurative sense, comes from the same telelocalising heights of American drones in Yemen or Pakistan, whose operators sit in the Creech Naval Base in Nevada or Langley, Virginia and bomb populations after abstracting pictures of ‘terror’ through what is known as ‘pattern of life analysis.’23

Telelocalising a milieu also means to provincialise its narrative; to make Egypt’s story absolutely its own. It is to enwrap the milieu of unrest into cocoons of national, regional or ethnic scenarios and not extend it to a world swept by uprisings and demonstrations from Mexico, Haiti and Honduras, to Madison and California in the United States, to Spain, Britain, France, Italy, Portugal or Greece in Europe. Why is it that the protests in Cairo or Alexandria have to be categorically isolated from the Tent City movements in Israel, tribal assertions against the government and mining multi-nationals in India, or the thousands who marched along the Des Voux Road in Hong Kong? Why is it that Friedman’s TSA can advance bravely along the Arab Street, but the street itself has to end as soon as it approaches absolutist oil rich allies like Saudi Arabia, Bahrain or the UAE? The primary impulse of informational news is to promote parcelled accounts of such eruptive events based on ethnographic, already existing diagnoses about which societies are mature enough to make an ‘orderly transition’ from authoritarianism to democracy (Iranians, perhaps Egyptians) and which people are clearly not (the Saudis). It is to engraft them agonistically into a singular unfolding narrative of capital in the world and foreclose a possibility of them merging with stories and histories that are different. The logic of ‘information’, taken in this special sense, is to present things as ‘already shot through with explanation’, as Walter Benjamin once said.24 This it does by nulling historical complexity, abolishing critical memory and reducing language to a set of linguistic functionalisms. When was the last time that viewers of Murdoch’s Fox News Channel, or even the more ‘liberal’ CNN, were reminded that it was only in 1953 that Iran had a democratically elected socialist Prime Minister?

So what is so essentially Arab about the Arab Spring? Why are the rumbles in the Arab world and distant thunders elsewhere symptomatic of not just this or that regime’s long pending disintegration, but of the planetary narrative of the Washington Consensus itself coming apart at the seams? Is the story simply a vulgar Freudian psychodrama of hitherto infantile but now slightly mature populations killing inclement fathers or demanding dignity or recognition from them? Why are the recent events in London to be deemed absolutely distant from the 60-odd food riots that, according to the US State Department, took place across the world in the last two years alone? In the month of April, 2011, the World Bank president, Robert Zoellick, said that the global economy is ‘one shock away’ from a catastrophic crisis in food supplies, estimating that in the last year alone 44 million people had ‘fallen into poverty due to rising food prices’.25 The United Nations’ FAO Food Price Index (FFPI) averaged 234 points in June 2011, 1 percent higher than in May and 39 percent higher than in June 2010.26 It had reached its peak at 238 points in February. This scenario of devastation is as much the outcome of expanding deserts, falling water tables, droughts and famines or increasingly hot Summers as it is of deregulated speculation on commodity futures and oil prices.27 It stretches from Haiti to Algeria, on to India and across up to the Philippines. It is tragically compounded by the fact, that while the techno-financial elites of Wall Street and its satellite formations across the world have long since recovered their fortunes lost in the downturn of 2007, according to the International Labor Organization’s 2010/11 Report, growth in global wages slowed from 2.8 percent in the beginning of the crisis to 1.5 percent in 2008 and 1.6 percent in 2009.If China is taken away from the picture, the figures come further down to 0.8 percent in 2008 and 0.7 percent in 2009.28

How indeed can movements in London be insulated from the hot winds blowing in from Cairo? Perhaps, the Egyptians may take heart in the fact that, despite their tribulations, according to the CIA’s World Fact Book, they, in being placed 90th, rank much lower than the US (39th) and are almost on a par with Tony Blair’s England (92nd) as far as income inequality is concerned.29

Conclusion

There have to be other forms of reckoning with such world wide eruptions of antagonistic energy and affect. The global landscape of violence has to be mapped in coincidence with an equally expansive map of North Atlantic financial elites, their constable states, satellite plutocracies and techno-managerial oligarchies across the world. This is not just a landscape of gross class exploitation and debt enslavement, but also one in which not just populations, but entire forms of life can be systematically rendered ‘disposable’ in an instant, by long distance speculations, remotely controlled ‘structural adjustments’ or, in a more elementary manner, by predator drones. The rice farmers in the Philippines perhaps know that instinctively without tracking the intricacies of tariff walls, as do tribal folks in Central India who have been asked to vacate their habitats and the bauxite rich mountains they have been worshipping as gods for centuries; hungry populations in Ethiopia or Sudan discern that something is rotten when their governments sign surreptitious deals, leasing arable land to distant powers like South Korea or China; the rural people of the Qandahar and Helmand provinces in Afghanistan create their own cosmologies of meaning and affect given the fact that, according to a recent poll conducted by the International Council on Security and Development, 92 percent of males (women were not polled) do not know anything about 9/11 and 40 percent believe that the war it triggered was on Islam, with the rest concluding that it was on Afghanistan.30

Arjun Appadurai has talked about a global intuition of poor people.31 According to him, the cellular, osmotic powers of the financialisation of the planet operate insidiously, often minus the sound and fury of the clear and present nation state and its vertical instruments of welfare and repression. However, perhaps, at an affective-popular level, the processes and outcomes of neoliberal globalisation are being questioned in myriad ways, bringing them into critical proximity with past horrors of colonial genocide, enslavement, exploitation and development of underdevelopment by the rapid devaluation of local modes of production. I call these formations intense localisms, keeping in mind the etymological variant intendere, which means to intend. Intense localisms therefore, are local cosmologies of justice that emerge from clashes between alien inflictions coming from a distance, and rooted customs, juridical and theological perspectives, stories, world views, solidarities, and affectations.32 These determinations of justice are, in most cases, intended, despite the fact that planetary metropolitan narratives of governance, security and news (the powers behind which flout international law with impunity) attempt to overwrite them as directionless, chaotic, or pathologically beholden to ‘terror’. Intense localisms come to the fore in a world in which desire is democratised, but the means to it are acutely monopolised; in which the mobility and bargaining power of labour is brutally restricted, but the movement and reach of capital is extended to the production of social life in and of itself. Intense localisms have thus emerged in an hour of the abject dismantling of the postwar welfare state, the financial subversion of the postcolonial state through comprador elites, withdrawal of social security programs, rampant privatisation of all sectors including health, education and natural resources, the planetary technologisation of agriculture, extermination of the commons, abject formalisations of the very concept of citizenship, and summary destructions of ecological habitats and scenes of nativity. Each of these cosmologies of justice are unique in some way, yet they are also contiguous to each other. In their separate ways, they have called the new world order to judgement.

This planetary swell of antagonistic energies undoubtedly takes both good and bad forms. Some of them merge with movements attempting to forge a politics of the new (from vital student mobilisations in Chile to the Indignados in Spain, to youth agitators in Tel Aviv or Hong Kong); others are captured by state machines. Examples of the latter would be the folksy righteousness and suicidal statism of the recently minted American Tea Party, the swarm of ultra right, racist and anti-immigrant populisms in Europe (the BNP and the English Defence League in Britain, Le Pen’s Front National in France, Geert Wilders and the Party for Freedom in Holland, the Jobbik in Hungary, Jörg Haider in Austria, or the best-selling neo-fascism of Thilo Sarrazin in Germany); or even, in a different sense, the current undemocratic agitation in India led by Anna Hazare that calls for combatting corruption by the setting up of an absolutist extra-judicial paternalistic authority called the Lokpal.

Similarly, it must be said that good and bad impulses of a many armed, billion strong Islamic faith in the world will indeed intensely shape and influence such local cosmologies and moral economies. How can one justify cynical calls to control transformational possibilities in Egypt or Gaza because of the spectral Muslim Brotherhood or Hamas (which also happens to be the largest and most efficient humanitarian organisation in Palestine) when the American and Israeli democracies continue to be strongly impelled by hard right Christian groups and Zionist parties like Likud? Affirming the historical and political valence of Tahrir Square is to grasp it without any existing assurances about ‘security’ and ‘stability’ and ready at hand fears about Iran; it is to be critically open to its possibilities, both good and bad. It is, as Alain Badiou recently reminded us, also to approach it like a student and not some stupid pontificating professor, precisely in order to freshly learn the very ways of distinguishing the good from the bad.33 All parties in Tahrir Square – the students, the Marxists, the Nasserites, the incredibly brave women, and indeed the Muslim Brotherhood – have been and will continue to make history. And yet, as Marx observed in relation to a different scenario in the past, perhaps none of them will make it of their ‘own free will; not under circumstances they themselves have chosen.’34 Some such efforts will be tragic, some farcical and some victorious, but if there is indeed hope in the Arab Spring, it is that there will be collective energies that will keep renewing themselves and returning to break the dead calm of things.

Making a distinction between good and bad, as Deleuze often reminded us, is not the same as making an onto-theological one between good and evil. The latter is what the techno-determinism of the western informational world does, fragmenting the event into neatly packaged but eminently consumable isomorphic spectacles of twittering teens and shady Salafists; those that were joyous around Anderson Cooper and those that punched him; ones that love America and ones that hate her. Techno-determined information flow is a form of power that seeks to reduce complexity into fungible data. It is there to destroy historical memory, to annihilate imaginative powers, to foreclose different emergent ways of thinking and being in the world. What it tries to abort at every step is a vision of alterity, a glimpse of a different world that is imminent.

Anustup Basu <basu1@illinois.edu> is Associate Professor of English, Criticism and Cinema Studies at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. He is the author of Bollywood in the Age of New Media: The Geotelevisual Aesthetic (Edinburgh University Press, 2010) and co-editor of Figurations in Indian Film (forthcoming from Palgrave-Macmillan in 2012) and InterMedia in South Aisa: The Forth Screen (forthcoming from Routledge, 2012). He is also the executive producer of Herbert (2005), which won the Indian National Award for Best Bengali Feature Film in 2005-06

Note

This article was written in 22 September 2011 before Gaddafi's death

Footnotes

1 Thomas L. Friedman, ‘Lessons From Tahrir Sq’, The New York Times, 15 May 2011, http://www.nytimes.com/2011/05/25/opinion/25friedm...

2 See Peter Hart, ‘Friedman’s Bogus Advice on Palestinian Non-Violence’, 15 May 2011, http://www.fair.org/blog/2011/05/25/friedmans-bogu.... For more analyses and reportage on Palestinian non-violence, see for example Mary Elizabeth King, A Quiet Revolution: The First Palestinian Intifada and Nonviolent Resistance, New York: Nation Books, 2007; for rare journalistic reckonings see Mohammed Khatib and Jonathan Pollak, ‘Palestinian Nonviolent Movement Carries on Despite Crackdown’, 21 January, 2011, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/mohammed-khatib/post... and Yousef Munayyer, ‘Palestine’s Hidden History of Nonviolence’, 18 May 2011, http://www.foreignpolicy.com/articles/2011/05/18/p...

3 See Patrick O’Connor, ‘Nonviolent Resistance in Palestine’, 17 October 2005, http://www.ifamericansknew.org/media/nonviolent.html

4 I have no intention of condoning these rocket attacks or other war crimes perpetrated by Hamas (including using the Palestinian population itself as a shield), and the idea of justice should not be understood in terms of symmetric violence. However, as documented by Human Rights Watch, such attacks caused only 15 Israeli civilian fatalities in the course of the decade. Hamas has often stated that the rockets were intended to hit Israeli military installations and not civilian targets. At times, it has expressed regret and ‘sorrow’ for Israeli civilian deaths. See ‘Hamas “Regrets” Civilian Deaths, Israel Unmoved’, Reuters, 5 February 2010, http://www.reuters.com/article/idUSTRE6143UB20100205. On other occasions it has pointed out a fundamental asymmetry in the issue itself when it came to the aggressor Israel, which has regularly bombed and shelled women, children, and the elderly in Mosques, hospitals, and even schools. In the final analysis, the crudely manufactured Qassam and Grad rockets have no guidance system and have symbolically contributed more to the myth of Israeli insecurity and the concomitant spectre of Islamic ‘terror’ than achieved military objectives for Hamas. Sometimes the rockets have fallen short and hit Palestinians, as it happened on 26 December, 2008, for example, when a rocket hit a house in Beit Lahiya, killing two girls.

5 By December 2007, about 90 percent of factories and workshops in Gaza had closed down, primarily due to the lack of raw materials (Israel, at this point, was allowing only one-third to one-tenth of net requirements to pass through, including essential commodities like medicines, food, educational items, clothing, building and industrial supplies). Three-quarters of Gaza’s population was surviving on $2 a day and a perhaps toxic water supply. About 70 percent of agricultural fields in the narrow strip of land that is 45km long and 8km wide had been laid to waste because there was an acute shortage of pipes and pumps required for irrigation, and also because Gazans were not allowed to farm in the ‘buffer zone’ designated by Israel along the border, which constitutes nearly one-third of the total arable land. Fishing has been forcibly restricted to three nautical miles from the coast, even though it should be 20 as per the Oslo Accords.

6 In comparatively recent history, perhaps the greatest sin of the Palestinians has been to elect Hamas to power, with a 56 percent mandate, in the Palestinian Legislative Council, on 26 January, 2006.

7 Consider Benjamin Netanyahu’s recent rebuke to President Obama when the latter, following a long-standing American foreign policy position, suggested that a peace settlement be reached with Palestine based on the 1967 borders. That could not be done, said Netanyahu, because those borders have been rendered ‘indefensible’. In other words, there might arise, in the future, the need for further strategic annexations in order to secure the now indefensible borders themselves. Following up on Netanyahu’s assertion, Likud Party member and Deputy Speaker of the Israeli Knesset, Danny Danon, wrote an op-ed in The New York Times that suggested that, should Palestinians press for statehood through a United Nations General Assembly vote this September, Israel should pre-empt this process by completely annexing the West Bank, thus fulfilling a messianic tryst with destiny in the name of Greater Israel, and laying claim to the historic heartland of Judea and Samaria. This proposed annexation would of course be completed without extending citizenship rights to Arab-Muslims, who would remain a diminishing spectre of ‘terror’, now acutely cramped into areas progressively smaller than the 22 percent of their historic homeland, which is what the 1967 lines would have accorded to them. See Danny Danon ‘Making the Land of Israel Whole’, The New York Times, 18 May 2011, http://www.nytimes.com/2011/05/19/opinion/19Danon....

8 See Jacques Derrida and Bernard Stiegler, Echographies of Television, Cambridge, MA: Polity Press, 2002, p.4.

9 See Medea Benjamin and Charles Davis, ‘Stop Arming Dictators’, http://www.informationclearinghouse.info/article27...

10 Linh Dinh makes this astute observation in ‘Heartwarming Massacres from Iraq to Libya’, 31 March 2011, http://www.commondreams.org/view/2011/03/31

11 That is, without reminding the world of an essential calling of the Camp David accords, that Israel should withdraw its military presence from the West Bank. See http://www.jimmycarterlibrary.gov/documents/campda...

12 See for instance Naomi Klein, ‘Democracy Born in Chains: South Africa’s Constricted Freedom’, http://www.naomiklein.org/articles/2011/02/democra...

13 For an extended, insightful discussion, see chapter 1 of David Harvey, A Brief History of Neoliberalism, New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

14 Ronald Judy, ‘Reflections on Straussism, Anti-Modernity, and Transition in the Age of American Force’, in boundary 2 33.1, Spring 2006, p.40.

15 One of the most significant cases of such ‘information’ extraction through torture was of course that of Ibn al-Sheikh al-Libi, who, under duress, made the false confession that provided the material for Colin Powell’s notorious presentation to the UN Security Council to make the case for the Iraq war.

16 I of course allude to Marx’s extraordinary tract ‘The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte’ in Karl Marx, Surveys from Exile, David Fernbach ed., New York: Vintage, 1974, pp.143-149.

17 The Egyptian military has been described as a sort of General Electric type conglomerate that ‘virtually owns every industry in the country.’ See for instance Alex Blumberg, ‘Why Egypt’s Military Cares About Home Appliances’, http://www.npr.org/blogs/money/2011/02/10/13350183... and Tom Engelbert, ‘Egyptian Math’, http://www.commondreams.org/view/2011/02/14-2

18 Mubarak’s last Finance Minister, Youssef Boutrous-Ghali, was an IMF alumnus who was chair of its policy advisory committee. He has been sentenced, in absentia, to 30 years in prison on corruption charges. Boutrous-Ghali was clever enough to leave Egypt before the heat got too much. See Wael Khalil, ‘Egypt’s IMF-backed Revolution? No thanks: Year after year, the IMF praised Mubarak’s ‘progress’ signing up for its $ 3bn loan now hardly seems a break with the past’, in The Guardian, 7 June, 2011, http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2011/jun/0...

19 I borrow this expression from the oeuvre of Paul Virilio.

20 See ‘Tony Blair: Mubarak is not Saddam Hussain’, http://www.politicshome.com/uk/article/21498/tony_...

21 See http://data.worldbank.org/country/egypt-arab-republic accessed 11 June, 2011 and page 13 of the ILO Report accessible at http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgrepor...

22 See Amira Nowaira, ‘Egypt’s Day of Rage goes on: Is the World Watching?’, The Guardian, 27 January 2011, http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2011/jan/2....

23 The Pakistani newspaper The Dawn calculated in January 2010 that in 2009 alone, 44 predator drone attacks in the western tribal areas, especially North Waziristan province, killed 708 people, of which only 5 were certified terrorists. See http://archives.dawn.com/archives/144960. The going rate was thus 140 innocent civilians for every dead terrorist. The problem however is that some terrorists, like Illyas Kashmiri, reportedly killed in 2009 and then again in 2011, have a vexing habit of coming back from the dead.

24 See Walter Benjamin, ‘The Storyteller: Reflections on the Works of Nikolai Leskov’, in Illuminations. Ed. Hannah Arendt, London: Fontana, 1973, p.89.

25 See Eric Martin, ‘World’s Poor “One Shock” From Crisis as Food Prices Climb, Zoellick Says’ at http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2011-04-16/zoellick-...

26 See the World Food Situation Report at http://www.fao.org/worldfoodsituation/wfs-home/foo...

27 Paul Buchheit points out that in 2008 the publication Price Perceptions said, ‘index funds alone now own about 1 billion bushels of Chicago wheat compared to annual US production of about 500 million.’ See Paul Buchheit, ‘How Wall Street Greed Funded Egypt’s Turmoil’ in http://www.commondreams.org/view/2011/02/14-10

28 See the ILO report at http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgrepor...

30 See Farah Marie Mokhtareizadeh, ‘Over Wo(my)n’s Dead Bodies: On Surviving “Liberation”’ http://www.commondreams.org/view/2010/12/19 accessed 21 July, 2011. See the report itself in http://www.icosgroup.net/static/reports/afghanista.... Another report by the The International Council on Security and Development shows overwhelming antipathy towards NATO operations: http://www.icosgroup.net/static/reports/bin-laden-...

31 Arjun Appadurai, Fear of Small Numbers: An Essay on the Geography of Anger, Durham: Duke University Press, 2006, p. 36.

32 I am grateful to a group of brilliant colleagues and friends in India (Moinak Biswas, Prasanta Chakravarty, Rajarshi Dasgupta, and Bodhisattva Kar) who, in the course of a stimulating exchange of ideas across continents through Facebook, were of immense help in clarifying and conceptually enriching this trope for me.

33 See Alain Badiou, ‘The Universal Reach of Popular Uprisings’, http://kasamaproject.org/2011/03/01/alan-badiou-du...

34 Karl Marx, ‘Eighteenth Brumaire’, op. cit., p.143.

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com