Government Grime and the EMA Kids

Following the lazy misrecognition of the 'bunking' EMA protesters from various quarters of media and government, Dan Hancox sets out to explore the complicated and contradictory soundscape of these urban motley crews

Not for the first time, the mainstream media didn't even notice the EMA kids were there. On 9 December 2010, thousands of working-class teenagers came out in protest at the abolition of the Education Maintenance Allowance (EMA), clashed with riot police and attempted to storm Her Majesty's Treasury, as fires burned and Lethal Bizzle's ‘Pow!' resounded in Parliament Square behind them. And - for once - they couldn't even get arrested.

Because, student protests are composed of students, right? More commonly known by their long-hand nomenclature, bloody students. Middle-class undergraduates, taking a quick break from eating Pot Noodles in front of Countdown, or lentils in front of Jeremy Kyle, or hashcakes in front of Godard films, to indulge a fleeting, dilettantish flirtation with radical politics. The right-wing press inevitably delighted in their own disgust at this caricature, castigating what they saw as self-righteous, monied university students wasting police time and taxpayers' money. And the supposedly left-leaning press were little better, regurgitating the same kneejerk characterisations, dismissing the most significant outpouring of youth dissent in decades with a wave of the hand. New Statesman political reporter James McIntyre's solitary comment on #dayx3 (as the 9 December protest was known) was the following Tweet: "Rich kids on Cenotaph-why should taxpayers pay for them to go to uni? Oh for days when decent students protested abt wars not £."

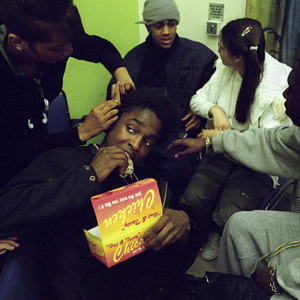

Image: Simon Wheatley, Inner City Youth, 2002

A protest populated by self-indulgent idle rich kids, petulantly rioting to secure an undeserved free education was a myth, as any journalist who bothered to abandon the comfort of their desks would have discovered. Firstly, the anger was real, and the targets of that anger were extremely broad: from library closures, to tax dodging corporations, to disability benefit cuts, to foreign oil wars, to NHS privatisation, to Trident renewal. But more than that, the people on the streets were not simply university students, middle-class or otherwise. The most accurate characterisation of the anti-government protesters in the mainstream media - the only journalist who came close - was Newsnight's Economics Editor, Paul Mason:

Any idea that you are dealing with Lacan-reading hipsters from Spitalfields on this demo is mistaken. While a good half of the march was undergraduates from the most militant college occupations - UCL, SOAS, Leeds, Sussex - the really stunning phenomenon, politically, was the presence of youth: bainlieue-style youth from Croydon, Peckham, the council estates of Islington.

It was the Conservative-Liberal Democrat government's abolition of the EMA, a means-tested weekly stipend to help poorer school pupils stay on in post-16 education, which was the catalyst for the seemingly spontaneous young working-class uprising. 'Seven in 10 poor teenagers would drop out of school if the EMA is abolished.' The Guardian reported, on the day the vote went through to dispose of it. 'And almost two-fifths (38%) say they would not have started their course had they not received the grant.'

In Paul Mason's mostly brilliant report, there was only one thing wrong, a mis-characterisation of the music these young people had been playing, partying, celebrating and rioting to in the Parliament Square kettle:

A crowd in which the oldest person was maybe seventeen took over the crucial jack plug, inserted it into a Blackberry, (iPhones are out for this demographic) and pumped out the dubstep. Young men, mainly black, grabbed each other around the head and formed a surging dance to the digital beat lit, as the light failed, by the distinctly analog light of a bench they had set on fire. With the Coalition's majority reduced by 3/4, it is unprecedented to see a government teeter before a movement in whom the iconic voices are sixteen and seventeen year old women, and whose anthems are mainly dubstep.

Image: Lordz of the Slum. A screenshot from Paul Mason's Newsnight report from the EMA protest, 9 December 2010

Mason got everything right, but the name of the music. I was there too, and their anthems are not dubstep, and this was not, as the BBC billed it, ‘the dubstep rebellion'. In a neat microcosm of Britain's diffuse 21st century urban music culture, the EMA kids gleefully danced, moshed, and threw themselves around to dancehall from Jamaica (Elephant Man's ‘Bun Bad Mind', Vybz Kartel's ‘Ramping Shop'), big-name pop from the US (Rihanna's ‘Rude Boy', 50 Cent ‘Just A Lil Bit'), and global club hits (Sean Paul - ‘Like Glue', Major Lazer - ‘Pon Di Floor') - though the most resounding anthems were two ferocious grime tracks, Tempz's ‘Next Hype' and Lethal Bizzle's ‘Pow'.

Does it really matter that a middle-aged financial journalist made a slight mis-step in youth music taxonomy, and mis-named this a dubstep rebellion? Not in the sense that he ought to be pilloried, especially as the solitary TV journalist - and one of about three journalists across the entire mainstream media - bothering to do actual reporting on these protests. Yet, it does matter.

If there ever really was a dubstep rebellion, it wouldn't have looked like the one the EMA kids started. This late in its life cycle, dubstep is many things to many people: radio-friendly chart pop music, coked-up laddish super-club music, university student union arms-round-the-shoulders moshpit music, ketamine sink-hole paranoid squat party music, politely hipsterish dinner party music - but the unifying battle-march of London's multi-cultural working-class it is not. It was taken up as a sobriquet because as a word, denuded of its original meaning, dubstep has floated close enough to the ears of the establishment - appearing in the broadsheets, on Skins, perhaps on the lips of their teenage children - that it can be fixed from above on a generation of young people for whom it is neither the source of anthems, nor the creative product: dubstep originates mostly in suburban Croydon, rather than the estates of inner and east London's poorer boroughs.

Image: Dancehall at Trafalgar Square from Dan Hancox's camera phone

It's one of a thousand examples of the repeated misunderstanding of the EMA kids, as filtered through music - at least it's less damaging when, as in Mason's report, it's used with the best of intentions. The real problem is that serious attempts to engage with this demographic are extremely rare, and more often, they are dismissed with Britain's unique, unapologetic 21st century minstrelsy, which takes the form of media characterisations that revel in a vernacular they neither understand, nor wish to understand. There are few more revolting experiences in modern Britain than turning on Radio 4 to hear a middle-aged, middle-class, white comedy actor playing a generic urban yoof: ‘bruv', ‘blud', ‘innit', ‘yagetme', ‘brrap' and most of all, the fictitious patois construction ‘I is well... [happy/sad/angry]'. Sasha Baron Cohen has a hell of a lot to answer for.

The popular myth constructed around this generation takes the form of an unholy trinity: first, impressionable, pitiable urban youth; second, aggressive urban music, which might be called grime, rap, dubstep, garage... at the level the myth is constructed, the terminology doesn't matter one jot; third, violence, bloodshed and moral degeneracy. In this characterisation, the three are inextricably linked, and propel each another forwards into a dystopian horizon. One classic articulation of the myth came from cricketer Andrew Flintoff, interviewed in The Sun in 2009 under the headline ‘Horrified Freddie raps rap music': 'Flintoff has claimed that RAP music is to blame for Britain's exploding levels of knife crime. The England ace slammed Broken Britain - and also blamed many of the country's problems on rising immigration rates. The dad-of-four said: "You see these reports of stabbings, bottlings, shootings, and you think, 'What is happening to this country?' I think rap music has a lot to do with it. It makes it sound cool not to conform, and to be violent."'

Image: Simon Wheatley, Inner City Youth, 2002

A stupid sportsman saying something stupid to a right-wing tabloid is hardly a surprise, but the unholy trinity myth permeates much of the liberal elite too: Ned Beauman, a 20-something hipster novelist, wrote a comment piece for The Guardian entitled ‘Is violence holding grime back?' - the answer, it quickly became clear, was yes. 'Too often, grime beefs erupt into real bloodshed' he wrote, responding to the single incident of this kind that has ever happened - Crazy Titch's arrest for the murder of a rival. Technically of course, he's right: once is 'too often'. But just like the comically ignorant Flintoff, his only response to this alien culture was to revel in an orientalist re-imagination of east London: 'This is partly to do with grime's origins. Most of grime's stars come from deprived London boroughs like Hackney and Newham, where gun crime is out of control. But it may also have something to do with the sound itself - unlike two-step garage, its sexy predecessor, grime is intrinsically claustrophobic and furious.'

The most embarrassing of interventions has been the coinage ‘Brrrap Pack', by the very same tabloid that echoed Flintoff's bigotry. Noticing the astonishing originality of British urban music since early 2009, The Sun's gossipy entertainment section ‘Bizarre' launched The Brrrap Pack Tour, featuring the likes of Chipmunk, Tinie Tempah and Skepta. Search The Sun's website and you will find literally hundreds of articles referencing, with a proud sense of ownership, 'the Bizarre Brrrap Pack'. The same musicians the paper despises as purveyors of aggressive rap music are also now the nation's foremost pop stars - and the perfect way of reeling in the next generation of readers.

Indeed, on the pages of the same newspaper in 2009, the headline 'Rapper tried to kill pregnant ex' appeared. The story beneath detailed the sentencing of 18-year-old Brandon Jolie for a horrific attempted murder. Brandon Jolie also had a slowly burgeoning reputation on the grime scene, known as a producer called Maniac. In his year or two on the scene, he sat in front of a computer and made beats, and never once used a microphone. Never mind that his skills were closer to those of Brian Eno than those of Tupac: Jolie was a young black man from an estate who made music; so he's a rapper, right? Again, this blanket ignorance was not limited to The Sun: to this day, the headline on The Guardian website reads ‘Would-be rapper who tried to get pregnant girlfriend drowned is jailed'. Guns don't kill people; rappers do.

Image: Simon Wheatley, Inner City Youth, 2002

When bastions of traditional authority attempt to ‘reach out', and seek to engage with the young people often dismissed as ‘yoof' or ‘youths' (depending on how formal you're being in your prejudice), it's often musicians they turn to. This leads to some awkward paradoxes, with the same grime MCs whose lyrical vernacular thrives on highly witty bellicosity (a sample JME lyric: 'I will dislocate your nose / Furthermore, I'll sprain your lip / plain and simp / Box you up like you were David Blaine and shit') recruited for official anti-gun and anti-knife campaigns. I was once asked by Tower Hamlets Council to interview grime MC Jammer about being a ‘positive' role model (the EMA kids have only two kinds at their disposal - positive or negative), as part of a series of articles aimed at young people which the council titled ‘Drop The Shanks'. These projects, though usually well-intentioned, feel at best uncomfortable. The response of teenage fans on message boards like www.grimeforum.com wavers between incredulity (‘they're hypocrites - how can you write a gun track one minute then an anti-gun track the next'), quiet admiration (‘well I guess they're doing their bit, fair enough'), and more often, embarrassment, or even contempt for the musicians' treachery in associating with the authorities.

The songs are usually sanctimonious and clunkily written, an inevitable pitfall of writing to government commission: the most striking example was Roll Deep's 2006 track for a Metropolitan Police/Operation Trident song ‘Badman'. It received substantial press, TV and radio coverage in 2006, but failed both commercially, and, we can assume, in its ability to end the ‘epidemic' of violent youth crime in the UK. Many were suspicious of the Operation Trident patronage, connecting it to an anti-informant sensibility similar to the ‘no snitching' motto in American hip-hop culture. Yet mostly, it was rejected because it simply wasn't a very good song. Grime fans are discerning enough to know that morality in music is more complex than a good-evil binary, and that gun-talk from MCs is a) just an act, and b) consistently more entertaining than sententious anti-gun-talk - certainly government-commissioned anti-gun talk. Neckle Camp's reggae-sampling grime track ‘Serious Times' proves that conscious anti-gun messages can be both powerful, and sincere - but crucially, it wasn't written to commission.

The establishment's sporadic attempts to reach young people at risk from violent crime via their musical heroes have been naïve - but at least you can work out what the thought process is in those cases; unsophisticated, reductive and patronising though it is. A far stranger attempt to ‘reach out' to marginalised young ethnic minority Brits occurred last October, when grime MC Ghetts was signed up to write a song called ‘Invisible', encouraging young ethnic minority Brits to take part in the forthcoming 2011 census. Some grime fans regarded it as a worthwhile cause, though most were understandably perplexed. 'I don't really see the point,' one wrote: 'how will filling in a census form massively help the cause of equality for ethnic minorities in the UK? Just seems like a really random tune to make... what next, a dedication to the binmen?'

The project's official press release explains their slightly fuzzy logic: 'Young people can feel that they can't influence the future, but with the help of Ghetts we can encourage them to take one step towards making a real contribution to their communities. The census helps Government allocate resources to the areas that need them the most. The new track, Invisible, makes the point that people need to fill in and return the census questionnaire to make sure local and national authorities know where services such as transport, housing, hospitals, schools, community centres and libraries are needed for the future.'

The song itself is cringe-worthy, clunky government-commission fare. 'If minorities don't fill in the forms / what's the point in living in Britain at all? / There ain't nothing worse than being invisible' Ghetts spits on the chorus. The timing of the Census press release could scarcely be more inappropriate: the young people protesting the abolition of the EMA know exactly where government services are needed, exactly who it is rendering them invisible, and exactly who it is that's stifling their futures - and on 9 December, they responded accordingly.

Dan Hancox <danjhancox AT googlemail.com> is a freelance journalist writing for The Guardian and others, and the editor of the forthcoming Fight Back! A Reader on the Winter of Protest. More of his work can be found at danhancox.com

Info.

Simon Wheatley, Don't Call Me Urban! The Time of Grime, Northumbria Press, 2010

ISBN: 978-1-904794-47-9

http://inmotion.magnumphotos.com/essay/innercity

A panel discussion - GHETTS AND GUESTS GET POLITICAL - is taking place at the Rich Mix, 3 February 2010, 7pm. For more information and tickets see http://www.urbandevelopment.co.uk/industrytakeover

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com