Exodus

In her recent anthology Participation, Claire Bishop targets the suspect utopianism of relational aesthetics – a new model public art for the age of consensus. But, writes Paul Helliwell, her alternative reading of participation, made across a set of historical texts and concerned to preserve the autonomy of art, may have blocked itself with her deployment of the fashionable Jacques Rancière

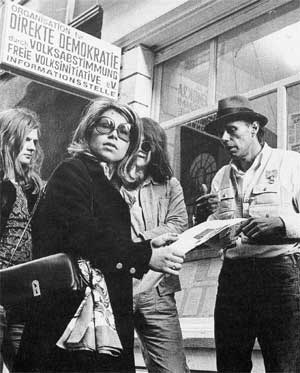

7.40pm. A total of 811 visitors of which 35 asked questions or discussed

– Report on a Day’s proceedings at the Bureau for Direct Democracy, Joseph Beuys and Dirk Schwarze

Participation is a reader charting the historical lineage and theoretical framework of an art concerned not just with the social production of the work – collaboration – but with the social relationships that the work itself is said to produce. Participation collects the writings of philosophers (from Umberto Eco to Jacques Rancière), artists (Guy Debord [sic] to Hirschhorn), and of curators and critics (Nicolas Bourriaud to Hal Foster), each in chronological order, from the 1950s to the present. But why review a collection of articles that have mostly already been published elsewhere?

Joseph Beuys, Bureau for the Organisation of Direct Democracy, Documenta 5, 1972

Bishop opens up the prehistory of participation prior to relational aesthetics, drawing on dada, the surrealists and continuities with ’60s movements such as happenings (Alan Kaprow) and performance art, delving both into their theoretical bases and non-European histories (Hélio Oiticica, Graciela Carnevale). Her aim is to bring back what was sidelined by the first manifesto of relational art: Bourriaud’s 1998 Esthétique Relationelle (published in English in 2002 as Relational Aesthetics). She seeks to replace Bourriaud’s curatorial and formalist responses with Eco’s ‘The Poetics of the Open Work’, arguing a creative misreading of this text underlies relational art. Bourriaud, her argument runs, misreads Eco’s example of aleatory or chance based classical music to explicitly require participation as the guarantor of openness, whereas for Eco all works of art are open in that they can provide an unlimited range of readings. Bishop has declared relational aesthetics itself an open work, and her previous articles in October magazine and Artforum have sought to reinsert art criticism into its circuits, not to save her own job (as Grant Kester suggested) but to save the participatory impulse in art.[1] Her intention has been to disentangle the claims made for it aesthetically from the claims made for its (ameliorative) social effects that Bourriaud’s formalism collated.

Bourriaud views relational aesthetics as being in resistance to the instrumentalisation of the social; a notion of community is proposed that overcomes current blockages by attempting to fuse art and life. As the open work and community are brought together they take on a utopian glow (a parallel might be found in Attali’s ‘composition’ or the theatrical Impro of Keith Johnstone), and this glow migrates to the artist(s) as generosity (Janet Kraynak) and to the utopian claims made for the work itself (Bishop). What generates this glow, explains Bishop, is the idea that the work does not merely reflect social relations but can produce them as well, and this, Bishop says, is derived from several sources collected in her book; from Bourriaud’s productive misreading of Eco, from Debord’s situationism, from Peter Bürger’s theory of the avant-garde – or indeed, in October, from Althusser’s ideological state apparatus.

Rirkrit Tiravanija, Pad Thai, 1991-'96

Bishop’s critique is that this production of the social in relational aesthetics is poorly thought out and evidenced, and this is true, but this is also true of all forms of art. How does art do what it does? And what is it that it does? To ask what art ‘does’ shows us caught in a causal, determinist, productivist snare – and what do you do? Even among Marxist critics who should view the world as a totality, there is a tendency to link, in the last resort, base (material production) and superstructure (cultural production) in a vulgar determinist fashion (one misreading of Marxism as science) or a slightly less vulgar dialectical fashion. As long as art claims to be autonomous and to have a social effect at the same time, this problem of the aesthetic will remain and continue to call for solutions.

In his 2004 piece No Ghosts in the Wall (collected here) Rirkit Tirivanija solves the problem of having a retrospective of his participatory works by having an audioguide tour of empty spaces, in it he says he wants to take Duchamp’s urinal off its pedestal, hang it back on the wall and piss in it. The avant-garde is repudiated but echoed, the flow of commodities from life to art reversed. Relational art wants to be liked, but more – in a misreading of Bürger, who knows not to attempt these kinds of short cuts – it wants to be literally useful. The wilful innocence of Bourriaud’s ‘utopia trialled’ calls for its own replacement by the social engagement of Grant Kester. Bishop argues that the direct ameliorative outcome and the collaboration in the work come to outweigh the aesthetic outcome, dragging art off course into both activism and the arms of the state.

As Bishop points out in her Artforum article, in the UK relational art has become the form of public art, replacing its ‘heavy metal’ variety – a Henry Moore on every corner – and we can expect to see more of it with Bourriaud curating the Tate Triennial and with his co-founder of Paris’s Palais de Tokyo, Jérôme Sans, now at the Baltic. This is, Bishop argues, in part because an open participatory work is difficult to commodify and thus reliant on public or gallery funding, but also because it is unfinished and thus more easily judged on the basis of the quality of the collaboration than its aesthetics. While the deadpan quote from Beuys and Schwarze at the top shows the limitations of this approach, it still fits better with the recent political emphasis on consensus and an instrumental role for art in delivering ‘social inclusion’ than modernist ironmongery. Bishop identifies the key document in this process – François Matarasso’s Use or Ornament: the Social Impact of Participation in the Arts – but her account of how this came to be is curiously vague.

The Home Office, collaboration between Terry Farrell & Partners and Liam Gillick, begun 2002

‘The social turn in contemporary art has prompted an ethical turn in art criticism’, says Bishop, but she knows the situation is more complex. The crisis of community in the ’90s had also been felt within philosophy and influenced its ethical turn (Agamben, Levinas), providing art and art criticism with new tools. The emphasis on consensus within and outside of the art world is a reaction to, but also a product of, the 1980s neoliberal restructuring towards service economies, the so-called ‘end of history’ and the collapse of the political into the managerial. Relational art is made in this image, the emphasis on consensus, the downsizing of u- to-micro-topia(s), even the migration of activists into art is perhaps due to this. Bishop opposes socially engaged art with an Adorno-like reading of Rancière, one of a group of 1980s French ‘post-marxist’ theorists of community. Rancière rejects stage theories in their philosophical and social bases, viewing them as blocking both art and politics with, in this case, an ethical consensus. Bishop says, ‘the aesthetic doesn’t need to be sacrificed on the altar of social change, as it already inherently contains the ameliorative process.’ When paraphrased by interviewer Jennifer Ross as ‘art heals’ alarm bells start ringing, warning us of art’s ethical/therapeutic makeover.[2] The return of the aesthetic is cast in an ethical mode; even Rancière cannot escape..[3] Yet this formulation has seldom sounded more token, more of an immunisation.

Bishop’s intentions are revealed by what is missing from Participation. Omissions from her wish list include Barthes’ ‘From Work to Text’, (though its companion piece ‘Death of the Author’ is included) and Benjamin’s ‘The Author as Producer’ (a major loss). Guattari’s aesthetico-ethical Chaosmosis is present but the work it inspired, Negri and Hardt’s Empire and its chapter on the multitude is not. Kester and Matarasso should have been included to illuminate the afterlife of relational aesthetics as socially engaged art. Althusser, Rancière’s repudiated teacher, is missing. Haacke is missing. Thomas Hirschhorn is present but revealingly Santiago Sierra is missing.

In her articles Bishop has highlighted the relational art of these two artists as valuing antagonism, non-identification and autonomy, and exposing the context of the work as shot through by laws and economic interests instead of some infinitely extended playroom. Previously, Bishop mobilised Jean-Luc Nancy’s The Inoperative Community to justify this, together with Laclau and Mouffe’s Lacan-derived theory of subjectivity. In Participation she only notes Nancy’s citation by other theorists but not her own, and Laclau and Mouffe are absent. These theorists provide strong arguments against consensus, understanding the subject as decentred agency, and antagonism as the limit and necessary condition for society – though perhaps not as neatly as Rancière whom Bishop eventually selected to perform this role.

For Participation, Bishop chose and translated an extract from Rancière’s Malaise Dans l’Esthétique, and her introductory essay is based on his ‘The Emancipated Spectator’ (2004).[4] This was later reprinted in a section of March 2007’s Artforum on Rancière entitled ‘Regime Change’ – this coronation begs its own review, but for now I’d like to focus on the essay’s implications for Bishop’s argument. ‘The Emancipated Spectator’ provides an exit strategy for art from relational aesthetics and socially engaged art based on theatre’s attitude to its spectators and their alleged ‘passivity’. Rancière views Brecht, Artaud, and Boal as attempting to cure this, but also argues for the value of contemplation and critiques this division between activity and passivity as a partage du sensible (distribution of the sensible) – enjoining us to permit both sides of this argument, for privileging participation over passive viewing and vice versa. Almost to treat them, the extract from Malaise argues, both as elements in that familiar artistic strategy, as a collage, not a montage of historical stages. The passivity of the viewer is no longer a sin. The art world can now both eat its relational cake and, crucially also, move on with a clear conscience, following Rancière, out of a rapidly manifesting ethical regime.

What has been lost in Bishop’s choice of Rancière? It is against the letter (if not the spirit) of Rancière to block things, but put at the end of Participation Bishop’s introductory essay would read like an obituary for relational art – the tension between participation and passive contemplation has simply been sapped. While Rancière can be read to support both their positions, ‘The Emancipated Spectator’ makes it look as if the Kester/Bishop debate was not just last year’s thing but about nothing at all. Liam Gillick makes reference to the extract from Malaise, his praise for Rancière a little faint.

We might be ascribing an excess of potential to his reassuring assertion that visual combinations at the root of certain familiar artistic strategies transcend modernism’s endgames and postmodernism’s endlessly circulating relativisms … Nothing grand is being suggested here – just a way to understand what already appears to be the case.[5]

For the Bishop of October, Sierra’s work was ‘an expression of the boundaries of both the social and the aesthetic after a century of attempts to fuse them’. It was the relationship of Sierra’s Workers Who Cannot Be Paid Remunerated to Remain Inside Cardboard Boxes to the art audience watching, maintained in antagonism by each other, that made the work interestingly ‘minor key’. Imagine it as a conceptual piece without people: following Laclau and Mouffe it would be an encounter of full identities, not our blocked partial identities formed by each other. Gombrowicz‘s inter-subjectivity as difficulty reappears stripped of Bourriaud’s panglossian enthusiasm, as Hal Foster quotes Sartre in his article, ‘(often)… Hell is other people’. ‘Capitalism is bad’ is a message hardly worth paying admission to a gallery for (when it can be received for free on a daily basis), and yet Rancière is less than reassuring here. He is uncomfortable with works such as this which foreground art’s complicity – in an echo of Bourriaud, he views this as an attempt to block art, by asking questions to which the answer is already known. This may be the key to his ‘reassuring assertion’, being able to bring politics back to the table in such a manner (via an aesthetic regime fundamentalism) that blocks such investigations.

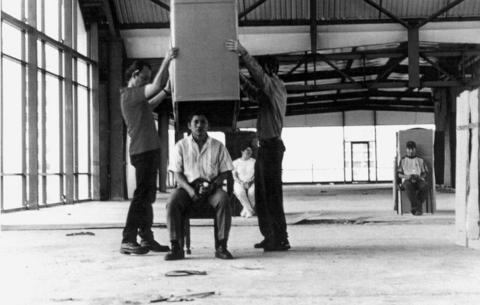

Santiago Sierra, Workers Who Cannot Be Paid Remunerated to Remain Inside Cardboard Boxes, 2000

In this respect the inauguration interview of the new regime, with Fulvia Carnevale and John Kelsey in Artforum, did not go (perhaps) entirely to plan. Rancière refused a distinction Carnevale made in her question, she went silent for a whole page before embarking on an institutional critique of the interview, the magazine and the art market itself:

Can one properly receive a reflection on these themes inscribed in a space that is half-filled with ads for galleries and half-filled with articles that serve to sell what is being shown in the galleries?

Behind this Rancière sees more blockage, the lurking spectre of Paolo Virno denouncing art as collaboration with capital and demanding exodus from it – in truth the presence of so much undiffused ideological state apparatus from the previous incumbents makes regime change difficult.

What any of them thought of the cardboard box trick when it was used in the last series of Big Brother is not known, but perhaps, being open works, other relational works have accidentally achieved antagonism. In Participation the post-1990 relational artists’ descriptions of their own work are hardly worth having: formalist, circumspect and non-directive, especially when compared to the enthusiastic letters between Clark and Oiticica. Bishop notes there are few reports on the sociability these works produce – here’s my contribution. A friend recounted a visit to Rirkit Tirivanija’s apartment (as relocated to the Serpentine art gallery). She was upset to discover it had been commandeered by gallery staff for use as a chill out space and that a heterosexual couple seemed intent on using the bed for reproductive purposes. It was, she said, more alienating than any conventional art show.

Bishop herself looks to sociology to provide a better understanding of what ‘inclusion’ and ‘participation’ mean in socially engaged art; she looks to Lacan to work out a link between the ethical and the beautiful. She is trying to write a book on socially engaged art – but in choosing Rancière, Bishop may have blocked her own work. Participation itself, as both book and practice, remains a toolkit to rewire art and life, but few sources in this book are mobilised as full collaborators – Bishop has left that as work for the reader.

Info

Participation, edited by Claire Bishop, Whitechapel and MIT Press, 2006

FOOTNOTES

[1] Claire Bishop, ‘Antagonism and Relational Aesthetics’, October 110, Fall 2004, http://roundtable.kein.org/files/roundtable/claire%20bishop-antagonism&relational%20aesthetics.pdf, and, Claire Bishop, ‘The Social Turn: Collaboration and its Discontents’, Artforum, February 2006, http://www.artforum.com/ – you’ll have to register.

[2] Jennifer Roche, ‘Socially Engaged Art, Critics and Discontents: An Interview with Claire Bishop’, July 25, 2006, http://www.communityarts.net/readingroom/archivefiles/2006/07/socially_engage.php

[3] For a good discussion of this see, Sarah James, ‘The Ethics of Aesthetics’, Art Monthly, March 2005, http://www.artmonthly.co.uk/ethics.htm

[4] Jacques Rancière, ‘The Emancipated Spectator’, Artforum, March 2007, p.271-280. Available as a video lecture bit torrent from http://theater.kein.org/

[5] Liam Gillick ‘Vegetables’, p.265 and 341, Artforum, March 2007.

Paul Helliwell <phelliwell2000 AT yahoo.co.uk> would like to thank Martin Denyer for his assistance and direct people to the myspace site of his ‘brother ass’, horsemouth, www.myspace.com/horsemouthfolk

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com