Bitcoin – finally, fair money?

Bitcoin is a decentralised digital currency deploying peer-to-peer networking to enable secure and anonymous transactions without a central bank. Unlike many economic commentators, The Wine and Cheese Appreciation Society and Scott Lenney take the currency seriously but ask, how exactly does it differ from 'real' money?

In 2009, Satoshi Nakamoto designed a new electronic or virtual currency called Bitcoin, the goal of which was to provide the equivalent of cash on the internet.i Rather than using bank or credit cards to buy stuff online, a Bitcoin user will install a piece of software, the Bitcoin client, on his computer and send Bitcoin to other users directly under a pseudonym. One simply enters into the software the pseudonym of the person one wishes to send Bitcoin, the amount to send, and the transaction will be transmitted through a peer-to-peer network.ii What one can specifically obtain with Bitcoin is somewhat limited to the few hundred websites which accept them, but includes other currencies, web hosting, server hosting, web design, DVDs, coffee in some coffee shops and classified adverts, as well as the ability to donate to WikiLeaks and to use online gambling sites despite being a US citizen.iii However, what allowed Bitcoin to break into the mainstream – if only for a short period of time – is the Craigslist-style website ‘Silk Road’ which allows anyone to trade Bitcoin for prohibited drugs.iv On 11 February, 1 BTC (Bitcoin) exchanged for $5.85, 8.31 million BTC were issued so far, 0.3 million BTC were used in 8,600 transactions in the last 24 hours and about 800 Bitcoin clients were connected to the network. Thus, it is not only some idea or proposal of a new payment system but an idea put into practice, although its volume is still somewhat short of the New York Stock Exchange.

The three features of cash which Bitcoin tries to emulate are anonymity, directness and lack of transaction costs, all of which are wanting in the dominant way of going about e-commerce using credit or debit cards or bank transfers. It’s purely peer-to-peer just like cash is peer-to-peer. So far, so general. What makes the project so ambitious is its attempt to provide a new currency. Bitcoin is not a way to move Euros, Pounds or Dollars around, it is meant as a new money in itself – it is denominated as BTC not £s. In fact, Bitcoin is even meant as a money based on different principles to modern credit monies. Most prominently, there is no ‘trusted third party’, no central bank in the Bitcoin economy and there is a ceiling limiting supply to the final figure of 21 million.v As a result, Bitcoin appeals to libertarians who appreciate the free market but are sceptical of the state and, in particular, state intervention in the market.

Because Bitcoin attempts to accomplish something well known – money – using a different approach, it allows for a fresh perspective of this ordinary thing, money. Since the Bitcoin project chose to avoid a trusted third party in its construction, it needs to solve several ‘technical’ problems or issues in order to make it viable as money. Hence, it points to the social requirements and properties which money must have in order to function as such.

In the first part of this text we want to explain how Bitcoin works using as little technical jargon as possible and also what Bitcoin teaches us about a society where free and equal exchange is the dominant form of economic interaction. From this follows a critique of the libertarian ideology behind it.

The first thing one can learn from Bitcoin is that the characterisation of the free market economy by some (libertarian) Bitcoin adherents (and most other people) is incorrect; namely, that exchange implies mutual benefit, cooperation and harmony.

Indeed, at first sight, an economy based on free and equal exchange might seem like a rather harmonious endeavour. People produce stuff in a division of labour such that both the coffee producer and the shoemaker get both shoes and coffee; and that coffee and those shoes reach their consumers via money. The activity of producers is to their mutual benefit or even to the benefit of all members of society. In the words of one Bitcoin partisan:

If we’re both self-interested rational creatures and if I offer you my X for your Y and you accept the trade then, necessarily, I value your Y more than my X and you value my X more than your Y. By voluntarily trading we each come away with something we find more valuable, at that time, than what we originally had. We are both better off. That’s not exploitative. That’s cooperative.vi

In fact, it is consensus in the economic mainstream that cooperation requires money and the Bitcoin community does not deviate from this position: ‘A community is defined by the cooperation of its participants, and efficient cooperation requires a medium of exchange (money)’.vii Hence, in their perspective on markets, the Bitcoin community agrees with the consensus among modern economists: free and equal exchange is cooperation and money is a means to facilitate mutual accommodation. They paint an idyllic picture of a ‘free market’ whose ills are attributed to misguided state intervention and sometimes the misguided interventions of banks and their monopolies.viii

Cash

One such state intervention is the provision of money and here lies one of Bitcoin’s main features: its function does not rely on a trusted third party or even a state to issue and maintain it. Instead, Bitcoin is directly peer-to-peer not only in its handling of money – like cash – but also in the maintenance and creation of money; as if there were no Bank of England but instead in its place, a protocol by which all people engaged in the British economy collectively printed sterling and watched over its distribution. For such a system to accomplish this, some ‘technical’ challenges have to be resolved. Some of which are trivial, some of which are not. For example, money needs to be divisible, two £5 notes must be the same as one £10 note, and each token of money must be as good as another – it can’t make a difference which £10 note one holds. These features are trivial to accomplish when dealing with a bunch of numbers on computers, but two qualities of money present themselves as non-trivial.

Digital Signatures: Guarantors of Mutual Harm

Transfer of ownership of money is so obvious when dealing with cash that it’s almost not worth mentioning or thinking about. If Alice hands a tenner to Bob, then Bob has the tenner and not Alice. After an exchange (or robbery, for that matter) it is evident who holds the money and who does not. After payment there is no way for Alice to claim she did not pay Bob, because she did. Nor can Bob transfer the tenner to his wallet without Alice’s consent except by force. When dealing with bank transfers etc., it is the banks who enforce this relationship, and in the last instance it is the police.

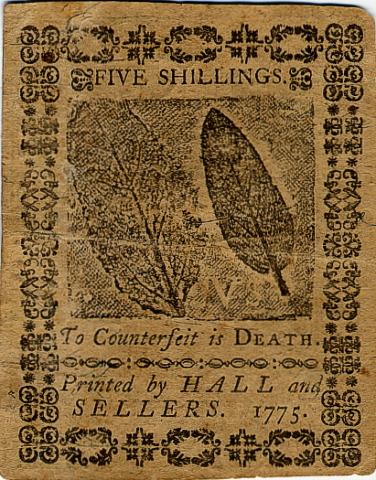

Image: Bill of credit issued by Hall and Sellers, 1775

One cannot take this for granted online. A banknote is now represented by nothing but a number or a string of bits. For example, let’s say 0xABCD represents 1 BTC.ix One can copy it easily and it’s impossible to prove that one does not have this string stored anywhere, i.e., that one does not have it anymore. Furthermore, once Bob has seen Alice’s note he can simply copy it. Transfer is tricky: how do I make sure you really give your Bitcoin to me?x This is the first issue virtual currencies have to address and indeed it is addressed in the Bitcoin network.

To prove that Alice really gave 0xABCD to Bob, she digitally signs a contract stating that this string now belongs to Bob and not herself. A digital signature is also nothing more than a string or large number. However, this string/number has special cryptographic/mathematical properties which make it – as far as we can ascertain – impossible to forge. Hence, just as people normally transfer ownership, say a title to a piece of land, money in the Bitcoin network has its ownership transferred by digitally signing contracts. It’s not the note that counts but a contract stating who owns the note. This problem and its solution – digital signatures – is by now so well established that it hardly receives any attention, even in the Bitcoin design document.xi

Yet, the question of who owns which Bitcoin in itself already problematises the idea of harmonic cooperation held by people about economy and Bitcoin. It indicates that in a Bitcoin transaction, or any act of exchange for that matter, it is not enough that Alice, who makes coffee, wants shoes made by Bob and vice versa. If things were as simple as that, they would discuss how many shoes and much coffee was needed, produce it and hand it over. Everybody happy.

Instead, what Alice does is to exchange her stuff for Bob’s stuff. She uses her coffee as a lever to get access to Bob’s stuff. Bob, on the other hand, uses his shoes as a leverage against Alice. Their respective products are their means to get access to the products they actually want to consume. That is, they produce their products not to fulfill their own or somebody else’s need, but to sell their products such that they can buy what they need. When Alice buys shoes off Bob, she uses her money as leverage to make Bob give her his shoes; in other words, she uses his dependency on money to get his shoes. And vice versa, Bob uses Alice’s dependency on shoes to make her give him money.xii Hence, it only makes sense for each to want more of the other’s for less of their own, which means depriving the other of her means: what I do not need immediately is still good for future trades. At the same time, one wants to keep as much of one’s own means as possible: buy cheap, sell dear. In other words, they are not expressing this harmonious division of labour for the mutual benefit at all, but seeking to gain an advantage in exchange, because they have to. It isn’t only that one seeks an advantage for oneself, but that one party’s advantage is the other party’s disadvantage: a low price for shoes means less money for Bob and more product for her money for Alice. This conflict of interest is not suspended in exchange but only mediated: they come to an agreement because they must, but that does not mean it would not be preferable to just take what they need.xiii This relation they have with each other produces an incentive to cheat, rob and steal.xiv Under these conditions – a systematic incentive to cross each other – answering the question who holds the tenner is very important: it’s a matter of getting what one needs or not.

This systemic production of circumstances where one party’s advantage is the other party’s disadvantage, also produces the need for the state’s monopoly on violence. Exchange as the dominant medium of economic interaction, and on a mass scale, is only possible if parties in general are limited to the realm of exchange and cannot simply take what they need and what they want. The libertarians behind Bitcoin might detest state intervention, but a market economy presupposes it. Wei Dai describes the online community as:

a community where the threat of violence is impotent because violence is impossible, and violence is impossible because its participants cannot be linked to their true names or physical locations.xv

In this way he not only acknowledges that people in the virtual economy have good reasons to harm each other but also that this economy only works because people do not actually engage with each other. Protected by state violence in the physical world, they can engage in the limited realm of the internet without the fear of violence.

The fact that ‘unbreakable’ digital signatures – or law enforced by the police – are needed to secure such simple transactions as goods being transferred from the producer to the consumer implies a fundamental enmity of interest of the parties involved. If the libertarian picture of the free market as harmonious cooperation for the mutual benefit of all was true, they would not need these signatures to secure it. The Bitcoin construction – their own construction – shows their theory to be wrong.

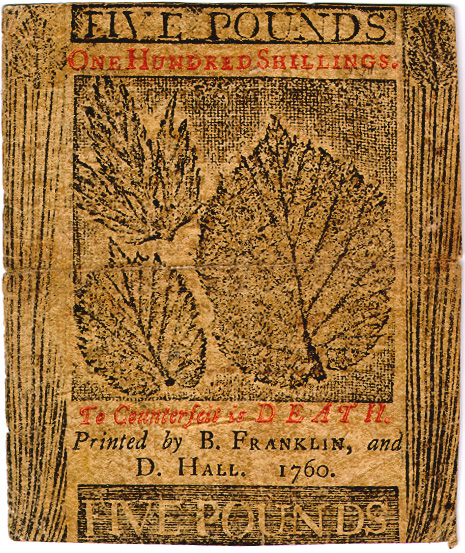

Image: Bill of credit issued by Benjamin Franklin and D. Hall, 1760

Against this, one could object that while by and large trade is a harmonious endeavour, there will always be some black sheep in the flock. In that case, however, one would still have to enquire into the relationship between effort (the police, digital signatures, etc.) and the outcome. The amount of work spent on putting those black sheep in their place demonstrates rather vividly how the expectation is that there would be many more without these countermeasures. Some people go still further and object on the principle that it’s all down to human nature, that it’s just how humans are. However, by proposing such a view, one first of all agrees that this society cannot be characterised as harmonious. Secondly, the statement ‘that’s just how it is’ is no explanation, even though it claims to be one. At any rate, we have tried above to make some arguments as to why people have good reason to engage with each other the way they do.

Purchasing Power

With digital signatures, only those qualities of Bitcoin which affect the relation between Alice and Bob are treated, but in terms of money the relation of Alice to the rest of society is of equal importance. The question needs to be answered – how much purchasing power does Alice have? When dealing with physical money, Alice cannot use the same banknote to pay two different people. There is no double spending, her spending power is limited to what she owns.

When using virtual currencies with digital signatures, on the other hand, nothing prevents Alice from digitally signing many contracts transferring ownership to different people: it is an operation she does by herself.xvi She would sign contracts stating that 0xABCD is now owned by Bob, Charley, Eve etc.

The key technical innovation of the Bitcoin protocol is that it solves this double spending problem without relying on a central authority. All previous attempts at digital money relied on some sort of central clearing house which would ensure that Alice cannot spend her money more than once. In the Bitcoin network this problem is addressed by making all transactions public.xvii Thus, instead of handing the signed contract to Bob, it is published on the network by Alice’s software. Then, the software of some other participant on the network signs that they have seen this contract certifying the transfer of Bitcoin from Alice to Bob. That is, someone acts as notary and signs Alice’s signature and thereby witnesses Alice’s signature. Honest witnesses will only sign the first spending of one Bitcoin and will refuse to sign later attempts to spend the same coin by the same person (unless the coin has arrived in that person’s wallet again through the normal means). They verify that Alice owns the coin she spends. The witness’ signature again is published (all this is handled automatically in the background by the client software).

Yet, Alice could simply collude with Charley and ask Charley to sign all her double spending contracts. She could get a false testimony from a crooked witness. In the Bitcoin network, this is prevented by selecting one witness at random for all transactions at a given moment. Instead of Alice picking a witness, it is randomly assigned. This random choice is organised as a kind of lottery where participants attempt to win the ability to be witness for the current time interval. One can increase one’s chances of being selected by investing more computer resources, but to have a decent chance one would need computer resources as great as the rest of the network combined.xviii As a side effect, many nodes on the network waste computational resources solving some mathematical puzzle by trying random solutions to win this witness lottery. In any case, for Alice and Charley to cheat they would have to win the lottery by investing considerable computational resources, too much to be worthwhile – at least that’s the hope. Thus, cheating is considered improbable since honest random witnesses will reject forgeries.

But what is a forgery and why is it so bad that so much effort is spent – computational resources wasted – in order to prevent it? On an immediate, individual level a forged bank note behaves no differently from a real one: it can be used to buy stuff and pay bills. In fact, the problem with a forgery is precisely that it is indistinguishable from real money, that it does not make a difference to its users - otherwise people would not accept it. Since it is indistinguishable from real money it functions just as normal money and more money confronts the same amount of commodities and as a result the value of money might diminish.

So what is this value of money, then? What does it mean? Purchasing power. Recall, that Alice and Bob both insist on their right to their own stuff when they engage in exchange and refuse to give up their goods just because somebody needs them. They insist on their exclusive right to dispose of their stuff, their private property. Under these conditions, money is the only way to get access to each other people’s stuff, because it convinces the other party to consent to the transaction. On the basis of private property, the only way to get access to somebody else’s private property is to offer one’s own in exchange. Hence, money indicates how much wealth in society one can get access to. Money measures private property as such. Money expresses how much wealth as such one can make use of: not only coffee or shoes but coffee, shoes, buildings, services, labour power, anything. On the other hand, money counts how much wealth as such my coffee is worth: coffee is not only coffee but a means to get access to all the other commodities on the market. It is exchanged for money such that one can buy stuff with this money. The price of coffee signifies how much thereof. All in all, numbers on my bank statement tell me how much I can afford, the limit of my purchasing power and hence – reversing the perspective – from how much wealth I am excluded.

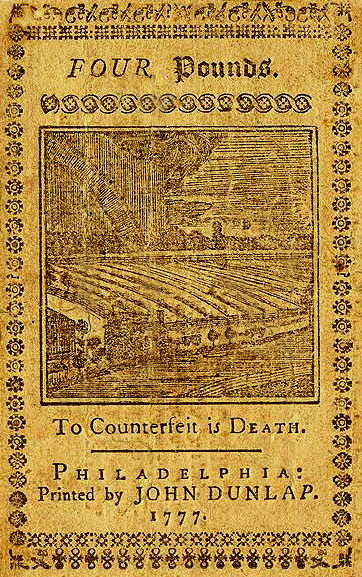

Image: Bill of credit issued by John Dunlap, 1777

From this it is also clear that under these social conditions – free and equal exchange – those who have nothing will not get anything, that the poor stay poor. Of course, free agents in a free market never have anything, they always own themselves and can sell themselves – their labour power – to others. Yet, their situation is not adequately characterised by pointing out that nature condemns us to work for the products we wish to consume, as the libertarians have it. Unemployed workers can only find work if somebody else offers them a job, if somebody else deems it profitable to employ them. Workers cannot change which product they offer, they only have one. That this situation is no pony farm can be verified by taking a look at the living conditions of workers and people out of work worldwide.

Money is power one can carry in one’s pockets; it expresses how much control over land, people, machines and products I have. Thus, a forgery defeats the purpose of money: it turns this limit, this magnitude into an infinity of possibilities, anything is – in principle – up for grabs just because I want it. If everyone has infinity power, it loses all meaning. It would not be effective demand that counts, but simply the fact that there is demand, which is not to say that would be a bad thing, necessarily.

In summary, money is an expression of social conditions where private property separates means and needs. For money to have this quality it is imperative that I can only spend that which is mine. This quality and hence this separation of need and means, with all its ignorance and brutality towards need, must be violently enforced by the police and on the Bitcoin network – where what people can do to each other is limited – by an elaborate protocol of witnesses, randomness and hard mathematical problems.

The Value of Money

Now, two problems remain: how is new currency introduced into the system (so far we have only handled the transfer of money) and how are participants persuaded to do all this hard computational work, i.e., to volunteer to be a witness. In Bitcoin the latter problem is solved using the former.

In order to motivate participants to spend computational resources on verifying transactions they are rewarded with a certain amount of Bitcoin if they are chosen as a witness. Currently, each win earns 50 BTC plus a small transaction fee for each transaction they witness. This also answers the question of how new coins are created: they are ‘mined’ when verifying transactions. In the Bitcoin network money is created ‘out of thin air’, by solving a pretty pointless problem. That is, the puzzle whose solution allows one to be a witness. The only point of this puzzle is that it is hard, that’s all.xix What counts is that other commodities/merchants relate to money as money and use it as such, not how it comes into the world.

Bitcoin, Credit Money and Capitalism

However, the amount of Bitcoin one earns for being a witness will decrease in the future – the amount is cut in half every four years. From 2012 a witness will only earn 25 BTC and so forth. Eventually there will be 21 million BTCs in total and no more.

There is no a priori technical reason for the hard limit of Bitcoin; neither for a limit in general nor the particular magnitude of 21 million. One could simply keep generating Bitcoins at the same rate, a rate that is based on recent economic activity in the Bitcoin network or the age of the lead developer or whatever. It is an arbitrary choice from a technical perspective. However, it is fair to assume that the choice made for Bitcoin is based on the assumption that a limited supply of money would allow for a better economy; where ‘better’ means ‘fairer’, more stable and devoid of state intervention. Libertarian Bitcoin adherents and developers claim that by ‘printing money’ states – via their central banks – devalue currencies and hence deprive their subjects of their assets.xx They claim that the state’s (and sometimes the banks’) ability to create money ‘out of thin air’ would violate the principles of the free market because they are based on monopoly instead of competition. Inspired by natural resources such as gold, Satoshi Nakamoto chose to fix a ceiling for the total amount of Bitcoin to some fixed value.xxi From this fact most pundits are quick to speculate over the likelihood of a ‘deflationary spiral’; i.e., whether this choice spells doom for the currency due to exponentially fast deflation – the value of the currency rising compared to all commodities – or not. Indeed, for these pundits the question of why modern currencies are credit money hardly deserves attention. Consequently, they miss what would likely happen if Bitcoin were to become successful: a new credit system would develop.

Credit

Capitalist enterprises invest money to make more money, to make a profit. They buy stuff such as goods and labour power, put these ‘to work’ and sell the result for more money than they have initially spent. For a capitalist enterprise, money is a means and more wealth – counted in money – is the end: growth.

If money is a means of growth, a lack of money is not a sufficient reason for the augmentation of money to fail to happen. With the availability of credit money, banks and fractional reserve banking, it is evident that this is the case. However, assume, for the sake of argument, that these things did not exist. Even then, at any given moment, some companies have money which they cannot spend yet while other companies need money to spend now (to buy new machines, say). Hence, both the need and means for credit appear. If growth is demanded, having money sitting idly in one’s vaults while someone else could invest and augment it is a poor business decision. This simple form of credit hence develops spontaneously under free market conditions.

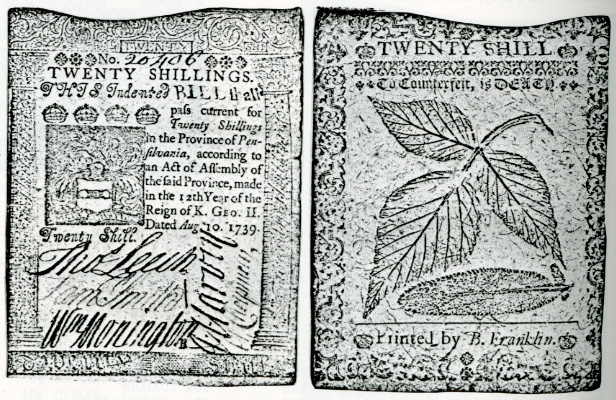

Image: Bill of credit issued by Benjamin Franklin, 1739

Furthermore, under the dictates of the free market, success itself is a question of how much money one can mobilise. The more money a company can invest the better its chances of success and the higher the yield on the market. Better technologies, production methods, distribution deals and training of workers, all these things are available – at a price. Now, with the possibility of credit the necessity for credit arises as well. If money is all that is needed for success and if the right to dispose over money is available for interest then any company has to anticipate its competitors borrowing money for the next round of investments, rolling up the market. The right choice under these conditions is to apply for credit and to start the next round of investment oneself; which – again – pushes the competition towards doing the same. This way, the availability of money not only provides the possibility for credit but also the basis for a large scale credit business, since the demand for credit motivates further demand.

Even without fractional reserve banking or credit money, e.g., within the Bitcoin economy, two observations can be made about the relation of capital to money and the money supply.

If some company A lends company B money, the supply of means of payment increases. Money that would otherwise be petrified into a hoard, kept away from the market, used for nothing, is activated and used in circulation. More money confronts the same amount of commodities, without printing a single new banknote or mining a single BTC. That means: the amount of money active in a given society is not fixed, even if Bitcoin was the standard form of money.

Instead, capital itself regulates the money supply in accordance with its business needs. Businesses ‘activate’ more purchasing power if they expect a particular investment to be advantageous. For them, the right amount of money is that amount of money which is worth investing. This is capital’s demand for money.

Growth Guarantees Money

When one puts money in a bank account or simply lends it to some other business, to earn interest, the value of that money is guaranteed by the success of the debtor to turn it into growth. If the debtor goes bankrupt that money is gone. No matter what the substance of money, credit is guaranteed by success.

In order to secure against such defaults creditors may demand securities, some sort of asset which has to be handed over in case of a default. On the other hand, if on average a credit relation means successful business, an IOU itself is such an asset. If Alice owes Bob and Bob is short on cash but wants to buy from Charley he can use the IOU issued by Alice as a means of payment: Charley gets whatever Alice owes Bob. If credit fulfils its purpose and stimulates growth then debt itself becomes an asset, almost as good as already earned money. After all, it should be earned in the future. Promises of payment can assume – and have assumed in the past – the quality of means of payment.

Charley can then spend Alice’s IOU when buying from Eve, and so forth. Thus, the amount of means of payment in society may grow much larger than the official money, simply by exchanging promises of payment of this money. And this happens without fractional reserve banks or credit money issued by a central bank. Instead, this credit system develops spontaneously under free market conditions and the only way to prevent it from happening is to ban this practice: to regulate the market, which is what the libertarians do not want to do.

Systematic enmity of interests, exclusion from social wealth, subjection of everything to capitalist growth – that is what an economy looks like where exchange, money and private property determine production and consumption. This does not change if the substance of money is gold or Bitcoin. This society produces poverty not because there is credit money but because it is based on exchange, money and economic growth. The libertarians might not mind this poverty, but those who have discovered Bitcoin as a new alternative to the status quo perhaps should.

The Wine and Cheese Appreciation Society of Greater London <wineandcheese@hush.com> is part of the Junge Linke gegen Kapital und Nation network. Its writings can be found at http://www.junge-linke.org/en

Scott Lenney <delasbas@hotmail.co.uk> writes about culture and politics

Footnotes

i The key white paper on Bitcoin is Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System by Satoshi Nakomoto, http://bitcoin.org/bitcoin.pdf

ii A peer-to-peer network is a network where nodes connect directly, without the need of central servers (although some functions might be reserved for servers). Famous examples include Napster, BitTorrent and Skype.

iii Probably due to pressure from the US government, all major online payment services stopped processing donations to the WikiLeaks project, see: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-11938320 Also, most US credit card provides prohibit the use of their cards for online gambling.

iv After Gawker media published an article about Silk Road - http://gawker.com/5805928/the-underground-website-... two US senators became aware of it and asked congress to shut it down. So far, law enforcement operations against Silk Road seem to have been unsuccessful.

v ‘Bitcoins are created each time a user discovers a new block. The rate of block creation is approximately constant over time: six per hour. The number of Bitcoins generated per block is set to decrease geometrically, with a 50 percent reduction every four years. The result is that the number of Bitcoins in existence will never exceed 21 million.’ http://www.bitcointalk.org/index.php?topic=3366.ms...

vii Wei Dai, 'bmoney.txt', http://weidai.com/bmoney.txt. This text outlines the general idea on which Satoshi Nakamoto based his Bitcoin protocol.

viii'The real problem with Bitcoin is not that it will enable people to avoid taxes or launder money, but that it threatens the elites’ stranglehold on the creation and distribution of money. If people start using Bitcoin, it will become obvious to them how much their wage is going down every year and how much of their savings is being stolen from them to line the pockets of banksters and politicians and keep them in power by fobbing them off with bread and circuses those who would otherwise take to the streets.’ http://undergroundeconomist.com/post/6112579823

ix For those who know a few technical details of Bitcoin: we are aware that Bitcoin are not represented by anything but a history of transactions. However, for ease of presentation we assume there is some unique representation – like the serial number on a five pound note.

x 'Commerce on the Internet has come to rely almost exclusively on financial institutions serving as trusted third parties to process electronic payments. [...] Completely non-reversible transactions are not really possible, since financial institutions cannot avoid mediating disputes. [...] With the possibility of reversal, the need for trust spreads. Merchants must be wary of their customers, hassling them for more information than they would otherwise need. A certain percentage of fraud is accepted as unavoidable. These costs and payment uncertainties can be avoided in person by using physical currency, but no mechanism exists to make payments over a communications channel without a trusted party.’ – Satoshi Nakomoto, op. cit.

xi For an overview of the academic state-of-the-art on digital cash see Burton Rosenberg (ed.), Handbook of Financial Cryptography and Security, CRC Press, 2011.

xii To avoid a possible misunderstanding,that money mediates this exchange is not the point here. What causes this relationship is that Alice and Bob engage in exchange. Money is simply an expression of this particular social relation.

xiii Of course, people do shy away from stealing from each other. Yet, this does not mean that it would not be advantageous to do so.

xiv 'Transactions that are computationally impractical to reverse would protect sellers from fraud, and routine escrow mechanisms could easily be implemented to protect buyers.’ Satoshi Nakomoto, op. cit.

xv Wei Dai, op. cit.

xvi 'The problem of course is the payee can’t verify that one of the owners did not double-spend the coin.’ – Satoshi Nakomoto, op. cit.

xvii 'We need a way for the payee to know that the previous owners did not sign any earlier transactions. For our purposes, the earliest transaction is the one that counts, so we don’t care about later attempts to double-spend. The only way to confirm the absence of a transaction is to be aware of all transactions’ – ibid. Note that this also means that Bitcoin is far from anonymous. Anyone can see all transactions happening in the network. However, Bitcoin transactions are between pseudonyms which provides some weaker form of anonymity.

xviii On the Bitcoin network anyone can pretend to be many people by creating many pseudonyms. Hence, this lottery is organised in such a way that one has to solve a mathematical puzzle by trying random solutions which requires considerable computational resources (big computers). This way, being 'more people' on the network requires more financial investment in computer hardware and electricity. It is similar to an ordinary lottery: those who buy many tickets have a higher chance of winning.

xix 'The only conditions are that it must be easy to determine how much computing effort it took to solve the problem and the solution must otherwise have no value, either practical or intellectual' – Wei Dai, op. cit.

xx 'The root problem with conventional currency is all the trust that’s required to make it work. The central bank must be trusted not to debase the currency, but the history of fiat currencies is full of breaches of that trust. Banks must be trusted to hold our money and transfer it electronically, but they lend it out in waves of credit bubbles with barely a fraction in reserve. We have to trust them with our privacy, trust them not to let identity thieves drain our accounts. Their massive overhead costs make micropayments impossible.’– Satoshi Nakamoto, Bitcoin creator, quoted in Jashua Davis, ‘The Crypto-Currency: Bitcoin and Its Mysterious Inventor’, The New Yorker, 10 October, 2011.p. 62.

xxi 'The steady addition of a constant amount of new coins is analogous to gold miners expending resources to add gold to circulation. In our case, it is CPU time and electricity that is expended.’ Satoshi Nakomoto, op. cit. Furthermore, the distributed generation of Bitcoin is inspired by gold. In the beginning it is easy to ‘mine’ but it becomes harder and harder over time. Bitcoin’s mining concept is an attempt to translate the return to gold money to the internet.

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com