Athens and the Bankers

The Greek crisis is often diminished to a simple story of Debt versus the People. Richard Braude moves between the symptomatic details of everyday life in Athens today and the deep history of the crisis to recover gleams of human possibility beyond the narrative of bad bankers and rad technocrats

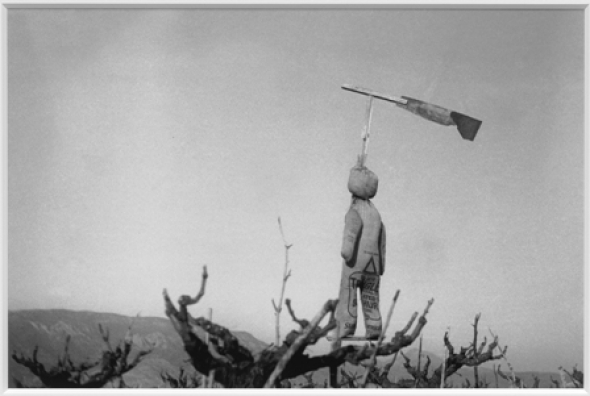

… and they would break their limbs giving them the shape of angels, and then exhibit them in fortified places, and in abandoned lots, where with great assembly and secret rites they would placate them, call them back. Until, with all the holier-than-thous, genuflection, and adoration, the domes covered over with flying corpses, dislocated bones, and awful fractures, postures of extreme agony, but also the most beautiful wings, tiny lights (so dreaded back then), human wheels that could tell the future – heads with eight tentacles like needles – and other wonders, harrowing but spectacular.

For in those days, it is said, heralds appeared with scissors, proclaiming.

– Jenny Mastoraki, ‘Depiction of a Rare Custom: vivid colors and impassive faces, as seen in still water’[1]

Heralds With Scissors

Greek political life seems full of figures not so much urged on by a voice miraculously speaking through them, but rather actors hurled by desperate stage hands into the spotlight, circulating prompt cards and stage directions among themselves. The blocking is thus somewhat haphazard, choreographic lines drawn in overlapping, uncomplementary ways, figures obscuring rather than being illuminated by the glorifying lights dangled above. The whirring servers of the networked left are now bloated with sociologies on the Greek people, class structure and political composition, all of which attempt to rearrange the lights and props to provide those clarifications necessary for clear thinking. Thus, we identified two sets of actors in this programme: the bankers and the politicians. The forces of darkness comprised of Schäuble, Dijesselbloem, Junker, Merkel. On the other side Tsipras, Varoufakis, Lapavitsas, Konstantopoulou to name a few.

The ethnic distinction burrows close to the surface. Perhaps Greece can indeed be considered to have always been a ‘vassal’ of European and then American powers.[2] Since 1830, when King Otto ruled, and the Greek state almost immediately defaulted under him, the processes of Greek nation building, including the unification of a Greek people, have been bound through the solidarity of debt as much as anything else.[3] And the State continued to default periodically every thirty years until 1893, when its finances were put under direct European control. That is to say, in the long durée, for geopolitical reasons, that strange mix of lithic accident and bellicose machination, today’s situation has its precedents.

Image: At Syntagma Square during the protest against the new bail out, July 2015. (Nikos Libertas / SOOC)

True, there might be ‘no other way to explain the latest stage of “negotiations” than as a veritable piece of theatre.’[4] But the actors started refusing to play their parts even while the curtain was being raised. Most of the ‘bankers’, after all, are politicians, even if elected into their posts on a set of policies only indirectly connected with the current Eurozone negotiations; even if, that is, in the figure of Dijsselbloem, with his perfect amalgam of colonial accents, we could hardly find a greater nobody, an imperially constructed blandness given meaning only by historical contingency which made him into capital’s most straight-talking mouthpiece. Similarly, the forces of good keep appropriating pesky technocratic features. Varoufakis flew in and out of the negotiations, an economist with a parachute and rocket pack. The night of the Great Capitulation, he presented his plan of IOUs, Grexit, tax hacking and dual power. Not enough of a plan, he was told apparently. The technocrat had failed to lead, to realise his true role. Lapavitsas bellows his fiery, almost theological Keynesianism, a modern Ranter, and declares that the banks need to be managed properly, in order to realise sustainable growth. One aspiring political scientist named the representatives of the Troika setting up shop in Athens ‘bureaucratic minions.’ It was clear from the discourse blaring out from his perfectly crafted beard that the problem lay in their being ‘minions’, rather than ‘bureaucrats’. ‘For a workers’ technocracy!’ seems the sotto voce chant.

Taking pot-shots at social democrats, verbally at least, is all too easy (for the physical ones, the police remain on watch). But the reigning sentiment in this new republic of disappointments is not only anger, but confusion. The old port is awash with rumours. A couple of journalists joke that the Greek economy is being buoyed by their own trade alone. The rumours are not limited to the press, but spill back out into the streets and ubiquitous cafés, eddies of sociological analysis and conspiratorial absurdity. Nothing is trusted. Putin pulled back on his promise of billions at the last minute. PASOK deployed moles in the secret service in the ’80s, who remain loyal to the old left. Tsipras has a quasi-religious, cultic commitment to the European project. The confusion revolves around the erring of the Syriza project. The path into electoralism precipitated a kind of faith far beyond its original support, a trusting of oneself, of one’s future, to a hidden plan. For a week, everything was possible politically. The People seemed to resurface at the very moment that the banks closed. The popular referendum was a negotiating chip but, like all tokens, it unleashed greater social forces than it at first intended to invoke. Which social forces, in what combinations, will never be fully delineated by sociology: a coin purports to be merely a mechanism of exchange, but in truth encapsulates all social relations within all the commodities it mediates. Coins, cards and tokens. Tsipras wanted a card to play in the Great Game; he got history instead.

The confusion of these days – a miasma of anger, despair, desperation, listlessness, lostlessness, passionate ambivalence – is the concussion suffered by a historical moment whacked round the head by the sledge hammer of diplomacy. The technocratic politicians entered into a diplomatic politics in order to confront the enemy - the political technocrats.[5] On the surface was a macro-economic problem: how to achieve economic growth whether with or without the Euro. Faced with the potential of a exit from the Eurozone, the Left Platform presented a plan of currency independence and economic transition to their colleagues, but in the productive world of the circulation of blame, apparently too little and too late.

Those defending Tsipras’s capitulation to the creditors pivot their arguments around the question of political timing, claiming that this was the only option, that the time was not ripe for an exit, or perhaps that political decisions go rotten in the sun.[6] This is not an argument crafted out of careful reasoning, but perhaps the only explanation available to those who wish not to fall into the ‘surrealism’ (as Tsipras has called it) of supporting the government but not their decisions.[7] The real incongruity, however, does not lie in the apparently inhuman act of holding two thoughts in one’s head at the same time, but rather it is that in entering into diplomacy, the technocrats found a political, not economic, contradiction. Different, irreconcilable forms of political technology were pushed up against each other, each attempting to incorporate the other into its own mechanism: the truck of Diplomacy clawing at a piston, trying to form it into a wheel, the blender of the People grasping for a blade in a console.

The truth is that a plan could not be developed properly or demonstrated earlier simply because the ‘vassal’ state of European powers, if dividing itself from essential German-State-controlled finance, would have had to find a new patron, be it Russia, America, Israel – whoever.[8] Such financing would have to come at a price: vetoes in the EU, border controls or openings, military bases, pipelines. So the rumours circulate and bob, like migrants, oil prices, and raised hands in election halls: food for banks, medicine for gas, and all the other gross equivalences imposed by the destructive pursuit of accumulation through state concordances. Even hiring a full complement of researchers (of which there are plenty in Athens) to put flesh on the micro-economic skeleton would jeopardise the process merely because diplomatic agreements, even in the polite world of Keynesianism, rely on their secretive nature, what the British Chancellor of the Exchequer in 1931, in refusing to inform the soon-to-be-ousted Prime Minister of his own secret Keynesian programme, termed ‘the universal practice of withholding information.’[9] Under the aspect of diplomatic politics, both politicians and bankers merged into a single figure: the gambler, whose categorical imperative is neither to play, fold, win or lose any particular round, but simply never to show his cards. Syriza proclaimed itself the party of the people, but could not bring the people in on their mechanical games. The accumulating time of history and the timelessness of the casino entered into each other.

Step away from the table, the green felt, the spinning wheels. Out through the doors, out into the air, away from the timeless, windowless chamber. There is no air conditioning in the Athenian streets, only the glare. The cafés are full, the drinks flow. The banks closed, liquidity calcified, wages stalled in the pockets of employers, even if the wage relation holds its course. But young Athenians aren’t on holiday, there’s too much insecurity for city breaks. So in hip Gazi and pristine Kolonaki the bars are fuller than ever. Capital controls, a Freudian tells me, have encouraged people to consume and copulate all the more. Researchers, engineers, journalists, photographers, teachers, philosophers, software developers, mostly unemployed, more confused than ever, pass the spirits round, along with their news and rumours. In the working class quarters and suburbs, it’s a different story. Even for the anarchists in run-down Exarchia, suspended mid-gentrification, who perhaps inadvertently put Syriza into power, Athens remains a functioning metropolis. The trains run, the air conditioning circulates, the drinks get topped up, even if people drink to forget the failures as much as to pick over the carcasses together, even if everyone knows someone who has lost everything.

Out to the port.

Abandoned Lots

Modern Athens never was a shipbuilding city. Despite the expansive shipyards, this was never the ‘industrial base’. Shipping, on the other hand, is the broken fulcrum of the national economy. The largest fleets in the world, but untaxed they may as well be financially as well as literally offshore. It was the merchant capital of the 19th century Greek bourgeoisie which accumulated into a nation, a revolution, an all encompassing banking system. For the great irony of considering Greece as subdued by a financial system is that it was formed as such. Ask about post-war economic boom, and the answer is inevitably ‘construction’, more often that not combined with a gesture towards the identikit concrete blocks of both central and suburban Athens. And yet capitalist economies do not function by construction workers building houses for each other, any more than a service sector can exist only to serve its composite waiters, cooks and cleaners, as busy and gleaming as some of the bars might be. Nor can tourism, any more than journalism, account for the entirety of Greece’s economic history.

The answer to the riddle is that the Greek banking sector, built on the back of two centuries of merchant capital, was the centre being served and built for.[10] It was this capital which backed the partial industrialisation of the 1950s and ‘60s, before the factories stalled and spluttered along with the rest of the West in the early 1970s.[11] Nowadays the agriculture across the country, profitable only through a combination of EU subsidies and €1 an hour migrant labour (a workforce quite literally subdued at gunpoint),[12] flows between the cosmopolitan centres without any industrial belt to speak of, only small manufacture and the ports dotting the coasts, although nearly all the large scale shipbuilding which did exist moved to South Korea long ago. The ascendency of the Greek State rode on its maritime capital, on a historic accumulation which distinguished it from its Balkan neighbours.[13]

This peculiarity of the Greek national economy explains why for so long it was the isolated Eastern member of the EEC (between 1981 and the accession of Bulgaria in 2007, without any bordering EEC or EU nation), why the cities are awash with English speaking graduates – in other words, why it was let into the boys’ club to start off with. For as much as Thomas Sankara’s critique of debt as the ‘cleverly managed reconquest of Africa’ finds a new and knowing avatar in Varoufakis, describing Greece as a ‘debt colony’, Greece has the exceptional circumstance of being in some way, unlike Burkina Faso, a debt colony which was welcomed into bourgeois society. The infamous oligarchs, the latest manifestations of merchant capital ‘standing up on its hind legs and demanding its share’, left their class character stamped across Europe’s conception of the Greek nation State. As the technologies of Empire return home, as they always do, Greece has been hit as more than just a physical and ideological periphery, but as something much closer to the centre of the dream of Europe’s current technocratic leaders: the appearance of an economy built on fictitious capital, without a proletariat to call its own. That is, the vision of the Greek State as dependent on German capital or American geopolitics (schema dear to a kind of nationalist anti-Imperialist opposition) dovetail neatly with the EU’s own ideological analysis of the Greek State as devoid of any proletariat, a middle-class service based economy which should settle its debts and, concurrently, get down to some real work.

Image: A visitor at the exhibition Humans, Paint, Iron. Perama ship repairing zone, October 2013. (Menelaos Myrillas / SOOC)

Of course, the workers themselves get hidden beneath this spectacular dream surface. To provide an argument about Greece’s historic capital is not to elaborate the lives of those who maintained and expanded the hoard. Almost a million Gastarbeiter, fresh from the Greek fields, who made their way into the German proletariat near the start of the EEC project in the early ’60s; perhaps half a million Albanian workers in the Greek olive groves and polytunnels now, at its potential end. Between these poles stands the industrial working class of Athens, the ones who stayed, and whose industry remained competitive even within the global markets of the South China Seas: the ship repairers of Perama, the stronghold of the Communist Party (KKE). There was a plan, I am told, going back to 2008 (while police cars burnt in the city centre) for all the ship repairing companies at Perama to be in an association which managed state funds for fixed capital investment. Currently Perama lacks a floating dock wide enough for the new, larger Suez vessels. The communist union, PAME, never buckled to the austerity demands, and though under-invested, the infrastructure of their stretch of the port remains in state hands. Under the Third Memorandum, however, a majority of shares are destined to be floated. Additionally, in opposition to the shelved investment plan, a free trade zone has been posited for the full stretch of the Attic docks. The boss of one of the many small repairing businesses, lamenting the lost nationalisation plans, explains to me that instead ‘it will be a new Great Wall of China, all the way around. Inside will be Chinese workers. On the outside, people starving. I’m really sorry about all this, this world we are leaving you.’

Aside from this industrial proletariat, there is the working class of the expansive, infamous service sector, into whose ranks the ship repairers are being manoeuvred, into exactly that mass least represented by the Communists. For an outsider, it is all too easy for every moment to inch towards a symbolic reading, like the Romantic English poet seeing the revolution in every French blossom and garland. So when someone describes the Communist Party, marching past the demonstration at Syntagma Square during the second vote on the new bail-out, as ‘stuck at the bottom of the hill’, accident appears as fate. While the protesters in the square ready their banners, an old man sets out his stall of Greek flags for sale. A while later, the anarchists move on to Exarchia, throwing ritualistic flames and bottles at the encroaching police. In the middle of the smoke and tear gas, a man tries to push-start his car.

Just north of Exarchia stands a bronze monument to a great general. Arrayed around its steps, two and threes light up the glass slugs of their crack pipes. Beyond the general and his consumers lie Aries’ Fields, a public park one corner of which, this summer, has been transformed into a temporary tent village of Afghani and Pakistani refugees. Led there by the ‘agents’ awaiting their next international transfer from their customers’ families, the camp is as much a virtual bus station as temporary residence. All have a 30-day permit to stay in Greece; almost none want to remain even that long. The destination is nearly always Germany.

The Shape of Angels

Faced with the immediate withdrawal of liquidity, of bank closure, the inability to purchase imports, of external devaluation and internal inflation, political and familial conversation has turned to the fairly brutal basics of the material economy. A hellish vision emerges of a world where tourists flow in and out, and Greek fleets dock and circle, but no food or medicine comes in. The solidarity economy as it stands can only provide a partial answer. It is reaching its limits already, as for the most part it is, in truth, no more than the willing redistribution of wealth by a generous middle and working class who have not thrown their hearts into the empty chasm where their own futures used to be. The bourgeoisie of course, and not only the oligarchs, have meanwhile siphoned their wealth off into Swiss bank accounts rather than Syrian mouths, leaving their class inferiors to bear the brunt of basic human compassion. There has nonetheless been a refusal, often through the language of Christianity, to engage en masse in the politics of the Golden Dawn (even if it punches above its weight through hidden networks and patent violence). The sacred heart has been easing off the pressure from the strawberries of blood. Who knows if that valve can be maintained, or for how long it will remain open, or if the desire for a national stimulus programme might close it shut.[14] The next three years of national austerity has been declared just as the personal austerity is reaching out to a new layer of people.

Any hope in Syriza remains with its ability to transform legislation (a low cost move) to catch up with the hopes of its political base: same-sex civil partnerships, the closure of detention centres, reform of the police, protection of the poorest from evictions, a regulated press.[15] Cheap to implement (compared with, say, hiring thousands of teachers), but all with their cost to the bourgeoisie and Church, whose power remains separate from and an impediment to that of the State. Without the hope of borrowing, of liquidity, even the ‘free’ reforms seem again limited through the threat of bankruptcy. Lapavitsas the Shaker’s damning rhetoric seemingly resounds within the social as well as economic spheres.

What to make of this age of riots and Keynes, dreams of fiscal stimuli charged through the calorific value of a Molotov? Capitalists will invest in Greek capital if assured of conditions of extreme industrialisation. The necessary proletarianisation has occurred; the process of industrialisation remains ethereal, but possible. Alternatively, some hope that if its fingers are snapped, national capital might instead take its hold, arguing that a better industrialisation could be achieved through protectionism and currency devaluation. But however much the Greek nation state can be prised apart from the supposed imperial Europe to which its fate has thus far been bound, it must find other sources of merchandise and liquidity. Even under conditions of protectionism, such an economic project ultimately cannot work without international, diplomatic exchange, i.e. resorting to other centres of capital, even if this were to happen alongside a contradictory ‘national popular’ movement.[16] In essence the only options currently available are whether the state will choose the provenance of its new international capitalists or not. Thus even if there is a break up of Europe into its composite nation states, national capital must still take on an international quality. Similarly, if Greece totally defaults then the current options facing Greece would pass over onto the EU level: how to turn inwards and protect, and how to reach across to other centres of capital. This matters, because the supposed method of surmounting the intractable problem of international capital, posed by others on the left, through the creation of a new Europe, bound by a progressive constitution, is perhaps a more realisable possibility than they believe, for despite the occasional nod towards the welfare of ‘migrants as well as “autochthonous” (i.e. indigenous) populations’, the demand may be returned in a distorted and far stronger form through the creation of a ‘national’ Europe, with still further fortified borders, gunboats and barbicans.[17] States, after all, must prove the worth of their word, and the value of their bonds.

Image: Donated clothes at Aries' Fields, August 2015. (Alexandros Michailidis / SOOC)

Image: Donated clothes at Aries' Fields, August 2015. (Alexandros Michailidis / SOOC)

Zizek, in the name of the ‘waiting game’ theory of Syriza’s strategy, claims that ‘true courage [...] is not to imagine an alternative, but to accept the consequences of the fact that no discernible alternative exists.’[18] The famous dialectician immediately fails to synthesise the opposition, plumping for one side over the other. There is always the danger that the invocation of dialectics can mask a necessary choice, can function as an excuse for an unjustified resignation. Yet limits constructed around the extrapolation of reasoning for different people within this world also have to be recognised, for the vast majority of people invoked in the second half of this essay – the shipbuilders, the migrant farm workers, the coffee servers, the disappointed, the dispossessed – simply were never faced with such a choice except in the realms of fantasy proper. State negotiations remain a qualitatively different kind of preoccupation for the agents of the first half, themselves limited to certain other forms of activity. That separation is, after all, the dynamic that has been untouched by the entire drama, even the invocation of a popular referendum. Is there in this situation perhaps a division of class between the ‘courage’ to choose, and the ‘imagination’ to overcome?

When Tsipras put the Troika’s proposals to the now infamous popular vote, the Communist Party refused to vote either yes or no. Syriza, they claimed, could only ever capitulate, as it had never replaced the forces of capitalism. The KKE’s proposed substitute of ‘scientific central planning’[19] surely resonates in the bones of the technocratic skeletons washing up on Greece’s shores as much as it might in the hopes of that newly formed proletariat whose lives have been dismantled by the same process in the wrong hands. This rejection of reformism turned its back on the tenderness which was always at the heart of revolutionary politics, just as much as comrade Zizek’s embrace turns revolutionism to the ends of capital. And yet, there is a magnetic logic in the advice they gave to their members to substitute the party’s own programme for the official ballot paper.[20] For a Stalinist party, one must admit, this was an incongruously situationist act. Rather than Tsipras’s invocation of surrealism, which merely indicated a contradiction, the KKE’s advice, put into other contexts, perhaps indicates a way through that very split between politics and the people: the refusal to accept the ballots, tokens and currencies of the present, the options laid before us by both national and international capitals, and instead to rewrite history and capital itself, disassembling its waves of accumulation, transforming all waters to foam.

Richard Braudie <richardb AT riseup.net> lives and writes in Palermo

My thanks to friends in Athens, especially Anna and her families, and to DK for invaluable comments and corrections

Footnotes

[1] Jenny Mastoraki, ‘Depiction of a Rare Custom: vivid colors and impassive faces, as seen in still water’, Tales from the Deep, (1983) in Karen van Dyck (Ed. and Trans.), The Rehearsal of Misunderstanding: three collections by contemporary Greek women poets, Hanover: University Press of New England, 1998, pp.122-123.

[2] Varoufakis reintroduced this now spreading term: http://yanisvaroufakis.eu/2015/07/14/on-the-euro-s...

[3] If he had cared to, Nietzsche would have pointed out that debt was the origin of ‘solidarity’, preserved in the German Solidarobligation, ‘joint debt’. See Thomas Fiegle, Von der Solidarité zur Solidarität, Munster 2003.

[4] Cognord, ‘Changing of the Guard’, The Brooklyn Rail, 13 July 2015: http://sicjournal.org/a-discussion-of-syrizas-refe...

[5] These are characterised as distinct from Syriza’s other enemy, the oligarchs, the confrontation with whom will in all likelihood guarantee Syriza’s re-election in the Autumn, with or without the beleaguered Left. This division is even carried through by the Marxist Lapavitsas, who reminds us that the oligarchs will be laughing if there is no Grexit; they are an audience member, not one of the actors in the diplomatic theatre.

[6] https://opendemocracy.net/can-europe-make-it/stathis-gourgouris/syriza-problem-radical-democracy-and-left-governmentality-in-g Of course, ‘we need time’ was also the reason given back in Februrary, but in response to the Troika, not the public: http://www.brooklynrail.org/2015/03/field-notes/if...

[7] Zoe Konstantopoulou has replied, claiming that ‘Protecting the constitution is not surrealism.’ Breton would no doubt agree.

[8] On Syriza, the Partito Democratico and Israel, see https://electronicintifada.net/blogs/ali-abunimah/...

[9] A. Morgan, Ramsay MacDonald, Manchester 1987, p. 172. The irony is that, in this, Keynes’s own advice was the mainstream response to the Great Depression – devaluate the pound, moderate public spending – to which Ramsay MacDonald capitulated, leading to the fall of the first Labour government, and the early experiments in the British welfare state. Lapavitsas’s own response now also includes devaluation and moderate spending: a damning indicator of quite how much the German ‘Ordonomic’ model has no intention of allowing the economic recovery of the Greek State, designed as it is to remove state decisions on spending altogether. See Werner Bonefeld, ‘Freedom, Crisis and the Strong State: On German Ordoliberalism’, New Political Economy, 17, 5, 2012, pp.633-656.

[10] Nicos Mouzelis, ‘Capitalism and Dictatorship in Post War Greece’, New Left Review 96, 1976, pp.57-80. Also see Vassilis K. Fouskas & Constantine Dimoulas, Greece, Financialization and the EU, 2013, chapter 4.

[11] The demands for welfare in the 1980s, which continued despite PASOK’s opening up of the state to the global market, perhaps stemmed from a demand to reform the family and the patriarchal agricultural base following the collapse of industry and the Dictatorship, and the strong feminist movement which followed. Women moved off the farms and into the waged workforce, at the same time as PASOK began a trend of public spending which partially contributed to today’s infamous deficit. This is an absurdly cursory interpretation of the relation between feminism and welfare in Greece gleaned from E. Stamiris, The Women’s Movement in Greece, again New Left Review, 1986.

[12] Kashmira Gander, June, 2015, ‘Greek court fines migrant strawberry pickers who were shot at for demanding pay’, http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/gre...

[13] A full appreciation of this point would require an analysis of the Civil War, as well as subsequent relations with the Eastern Bloc and Yugoslavia.

[14] The ‘strawberries of blood’ is the moniker for the strawberries harvested by suffering migrant labourers in Greece. The fact is inescapable that this crisis of the EU’s economic model has occurred alongside the partial disintegration of its external borders through the consistent courage and determination of a mass movement of workers and refugees, and the simultaneous reimplementation of internal borders that were meant to have been dissolved. Christian Salmon has made this point, albeit in a quite different way, in Le Monde: http://www.versobooks.com/blogs/2164-in-ventimiglia-an-un-sovereign-state-erects-its-borders Also recognised briefly in: http://www.versobooks.com/blogs/1885-syriza-wins-t...

[15] This is not to ignore the economic aspects of these reforms. Same sex civil partnerships, for example, would provide a modicum of much needed financial security for gay families. Simultaneously, these reforms are also involved in the political exchanges with Europe: the claiming, at least, of human rights as part of the necessary elements of being accepted into the political community.

[16] Kouvelakis, stalwart of Syriza’s Left Platform, cites and defends a ‘national-popular’ programme as outlined by Togliatti’s version of Antonio Gramsci, perhaps forgetting that this was not the politics which brought together the Italian communists and factory occupiers in the 1920s, but that of the PCI’s disastrous transformation into a social democratic coalition partner, eventually supportive of the ‘historic compromise’ of Italy’s neoliberal 1980s. Then again, perhaps the only way forward for Tsipras’s career would be to be arrested by Fascists, fill up some journals, and be cited in defence of another social democratic project 70 years hence, https://www.jacobinmag.com/2015/08/tsipras-debt-germany-greece-euro/ On the ‘nationalist’ danger, also see Stefano Fassina, ‘For an alliance of national liberation fronts’ http://yanisvaroufakis.eu/2015/07/27/for-an-alliance-of-national-liberation-fronts-by-stefano-fassina-mp/

[17] For example, Sandro Mezzadra, ‘Seizing Europe. Crisis management, constitutional transformations, constituent movements: http://www.euronomade.info/?p=462

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com