Summer of Hate

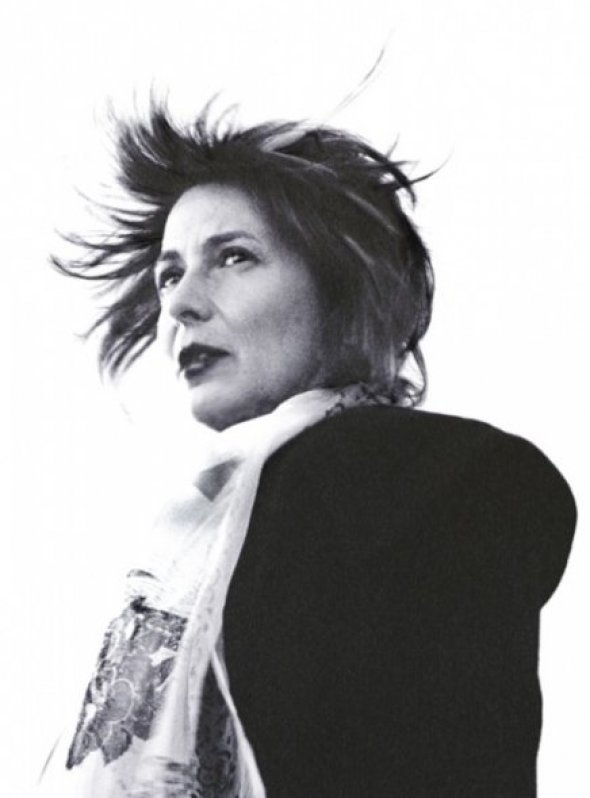

Hestia Peppe reviews Chris Kraus' Summer of Hate

Chris Kraus has a new book out. Conveniently described as a novel – a shorthand to distinguish it from her 'non-fiction' essay writing – Summer of Hate, like Kraus' previous exercises in fiction shows a certain disregard for the boundaries normally designating the real and the otherwise. It has more content in common with her theoretical work than might be expected given the formal distinctions between them. The work deals with a recent historical period, the first half-decade of the millennium, in the South Western states of America; a period which even our very fallible meat-memories have not yet completely consigned to narrative nostalgia. A character in the book observes, 'Isn't it weird, how nothing coming out now even mentions what's going on?'. Kraus attempts to do exactly that, to discuss the unspeakable reality that living in our times requires we mutely accept. Stories of New-Mexican locals' struggles with unemployment, petty crime, addiction and vagrancy mix almost eerily coherently with those of Bloomsbury reformers, academic tenure, utopias and BDSM. Kraus takes advantage of the fictional form's complex relation to truth in order to resist the impulse toward the semantic debate of mass media . 'Do not expect truth' she tells us and quotes Victor Klemperer writing about the Holocaust. 'Nazism permeated the flesh and blood of the people through single words, idioms and sentence structures which were imposed on them in a million repetitions and taken on board mechanically and unconsciously'. Theory as a dominant codification of language is morally implicated in this process and, consequently so is Kraus herself. She reminisces about a time before when 'The content hadn't been binarized yet to multiple choice'.

I don't want to construct an argument in relation to Chris Kraus. I was reading her at art school when I should have been reading Marx or Benjamin or Barthes so constructing arguments isn't, perhaps my strong point. Later on I read her again instead of reading something else, and over and over again. I guess that makes me a fan, though I don't self-identify as any of the types she itemises in Summer of Hate; 'Asperger's boys, girls who'd been hospitalised for mental illness, assistant professors who would not be receiving their tenure, lap dancers, cutters and whores' – at times I think I aspire to be all of those. My particular relation to this work is better characterised as romantic, as an avid reader of stories, than as academic.

Those fans she's describing are not, like me, fans of Chris Kraus, they're the fictional fans of the fictional Catt Dunlop whose voice emerges here, continuous with, yet undeniably distanced from the voice of Kraus in previous books both fictional and otherwise. Catt is and is not Chris, the lines blur, I tell myself to remember this one is fiction, and yet… I remember reading her short-lived blog on the social network Reality Sandwich some years ago now, writing then about that particular now and what were to become the themes of this book, the prison industrial complex in America, George W's dark flipside of the American Dream and spectral vestiges of romantic love in these shadows. It seemed then like it was about Chris. In the acknowledgments at the back of the book little traces of fact can be found, her 'consultant and partner' Phillip Valdez. Catt Dunlop's lover in Summer of Hate – Paul Garcia – did not I suspect spring fully formed from Kraus' imagination. For Kraus, fiction is a destabilising device. No less real than fact, perhaps more so, fiction is the hot lava of subjectivity. Reality creating itself through our selves. As I read I lose track of the boundaries between these crowding subjectivities, my own as well as theirs (and these pronouns become useless). This is the point I think I wish to make, and the reason perhaps she has not been widely read beyond the group of devoted fans already described. It is hard to tell what or who it is she is. But this is not a problem, this is her strength. We are confused and complicated.

In the year in which this novel ends, 2006, I spent some time in America; perhaps it was even then that I was reading the Reality Sandwich blog. I had read I Love Dick and Video Green and I was already in over my head, my internal narrative having entirely assimilated Kraus' voices. This is the effect of her fiction. Travelling down from San Francisco to LA and San Diego and then the deserts of California, Nevada, Arizona part of the rationale for the trip was to see 'the real America' so that I might distinguish between the fictional reality imposed on me through cultural imperialism and the actual lives of people there. I was nostalgic for motels and desert roads and with my two companions we sought them out. I didn't want to sightsee, I wanted to go to Quik-E-Mart and IHOP. I found the image-America to be as distant from and yet continuous with the America-under-my-feet as Catt Dunlop is to the Chris Kraus I finally managed to see in person at speaking engagements in London last year.

In Summer of Hate it is this fugitive 'real America' that Chris Kraus constructs for the reader, not an argument in relation to it. Fugitive like her character, Paul Garcia on the run across state lines and through clouds of booze and crack, like Catt Dunlop turning her back on the art world and its solipsism, fugitive like colours on a TV screen; constructed and unnatural, divorced from truth and yet actual and undeniable. Flipping houses in Albuquerqe, Catt 'plays a game of numbers', she supports her life in the cultural elite with small-time, small-town independent real estate deals. Chris Kraus has never flinched from describing the financial reality that affords the freedoms of her life but here we see it in detail. Gentrification is rarely discussed with such clarity by those who deliberately profit from it, nor by those in the art world who do so indirectly. In Summer of Hate it is not just houses being flipped, it is Paul Garcia, 'she cannot stop thinking about how obscenely rich she and everyone she knows in LA actually is.'

Catt's attempt to help Paul 'escape' from the misery and futility of his life after jail, to afford him access to education and culture mirrors perhaps her relationship with her older and more successful husband Michel, an iconic figure in his critical field who is broadly contiguous narratively with Chris Kraus' husband and co-founder of Semiotext(e), Sylvere Lotringer, very much a subject of Kraus' earlier works such as I Love Dick and Torpor. In that relationship it is Chris in the role of outsider, autodidact, foreigner, plus-one of a celebrated partner. In Summer of Hate the role reversal allows an entirely different aspect of life to be examined, the focus here is from the art world out, and Kraus' critical understanding can turn on the US social justice system, addiction and the ideology of twelve step and day-to-day experience of life under George W Bush but most importantly her own relation to that as a now successful individual, 'wealthy enough to pursue ideals beyond money'. Does the title Summer of Hate suggest some narrative inverse of The Summer of Love? Is the reality of neo-liberal America the inevitable outcome of the sixties dream? To what extent does our love for each other and the meaning we make become corrupted by capitalism? Part of the lawyer’s fee Catt pays in a final bid to save Paul from the notorious Maricopa County Jail 'will go towards the re-election of Sheriff Joe Arpaio’. Glimpsing the nauseating architecture of the status quo she pleads with herself: in a corrupt world wasn't enlisting corruption in your favour the right thing to do?'

Hestia Peppe is an artist and writer. She tends connections and keeps the homefires burning in South London. www.peepsgame.net

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com