The Who and Whom of Liberty Taking

The British Library's show Taking Liberties - on the struggle for freedom and rights throughout 900 years of British history - is a welcome event, writes Peter Linebaugh. But, he wonders, is it possible to discuss liberty while excluding the crucial question of equality?

Trying to make my way to the ‘shrine' in which Magna Carta is presented, I hover at the edge of a group of school children taking some liberties themselves - giggling and chatting while huddled on the floor to listen as their teacher prepares to offer them lessons in earnest. Mounted above is a quote from John Locke, the bourgeois theorist of competitive individualism and private property, ‘Where there is no law there is no freedom'. This is the note, at once abrupt and severe, upon which the exhibit begins. Clearly, this is an exhibit with an argument. (Hush now, children.)

Let's look at Locke more carefully.

For in all the states of created beings, capable of laws, where there is no law there is no freedom [...] freedom is not, as we are told, liberty for every man to do what he lists (for who could be free when every other man's humour might domineer over him?), but a liberty to dispose, and order as he lists, his person, actions, possessions, and his whole property, within the allowance of those laws under which he is.

This was written in 1689 against the English revolutionary antinomians, diggers, levellers, those without money and those who'd turn the world upside down. They were familiar with custom and solidarity. They did not do with their persons, property, and possessions as they list, but laboured to subsist with others. The humour of woman and man may be to cooperate. For truly the stance to law was different for the commoner (s/he ducks) than the bourgeois citizen (s/he puffs), as explained in Christopher Hill's powerful book Liberty Against the Law (1996). As the attitude to law differs, so does the take on liberty. Thus warned, I advance into the exhibit.

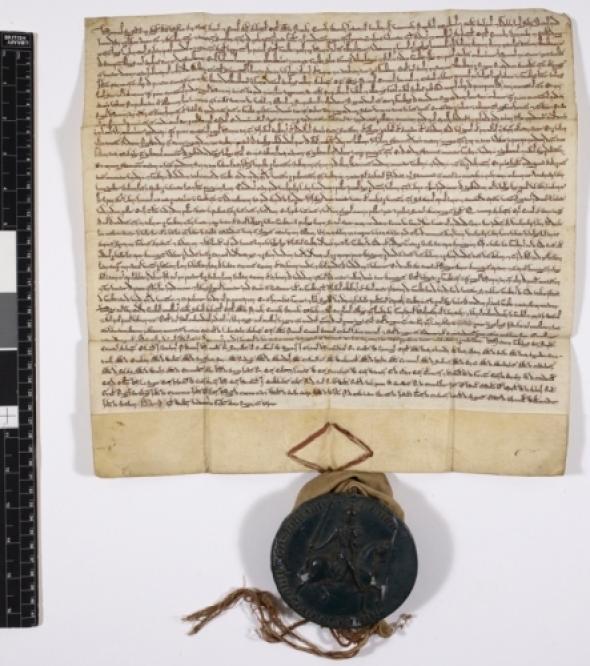

Image: Laws of Forests, 11 Feb, 1225

Wow! There is Magna Carta! The medieval Latin, the minuscule clerical writing, the dim lighting are all too much for most of us, obscuring what the exhibit as a whole wants to be made legible, visible and comprehensible. A banner above Magna Carta quotes chapter 39 in English translation (‘No free man shall be seized or imprisoned [...] except by the lawful judgement of his equals or by the law of the land'). A translation would be a welcome gift of the library to the patrons, in keeping with the wired wristband you pick up at the beginning to permit you to record your own opinions in the interactive consoles as you make your way from one group of exhibit cases to another. Fake, crumbling cement walls partition these different areas with the reinforcing rods showing through as if the walls were recently bombed or destroyed. Coming as I do from the USA, I think of Fallujah or our domestic gulag which is greater than any other country in the world proportionally to the population. Despite chapter 39, prison destruction is not a theme.

This is an important, interesting exhibition, and however you may stand on the arguments implicit and explicit in its organisation and selection, it is worth a visit and costs nothing. There is an amazing variety of objects on display - parchments, seals, jugs, truncheons, a purse, a funeral card, a diary, a notebook, a medal, a doll, paintings, cockade, banners and flags. Many, many items signifying liberty. The indirect ones hit hardest, like Emily Davison's unused return ticket to London (she had not planned to be crushed under the hooves of King George's horse).

It doesn't take long to simply walk through the exhibit. The areas are marked: 1) Liberty and Rule of Law, 2) Parliament and People, 3) Right to Vote, 4) United Kingdom?, 5) Freedom from Want, 6) Human Rights, 7) Freedom of Speech and Belief, 8) Interactive Results and 9) Your Thoughts. The more you pause and study the more you enter into the labours of history.

The great documents of the 17th century are here: the death warrant of Charles I (1649) signed by 57 regicides; the Petition of Right (1628); Coke's Institutes (1642) with their revolutionary theories of law; the notebook recording the Putney Debates (1647) and the egalitarian cry of ‘the poorest he' against the fears of property; the Agreement of the People (1649) is a huge document almost from ceiling to floor; the Habeas Corpus Act (1679) with its explicit condemnation of overseas rendition of trials and torture. These are the treasures much revered by the early working class movement of the 19th century.

A tone of smugness mars the exhibit. The jetlagged traveller making his way from Heathrow peers out the window of the tube to see the poster in the passing Underground station, ‘In some Countries you wouldn't have the right to visit this exhibition about your rights.' What humbug! Unless the exhibit is going to travel? Is it a reference to China? Very early in the exhibit there is the story of Sun Yet-Sen and his detention in the Chinese legation until a British judge, citing Magna Carta, ordered his release in 1896. These documents have become part of a world archive. After the Americans permitted the destruction of the archives and library of Iraq containing humanity's record of the first cities, we're reminded that the British Library, Linda Colley puts it, ‘is an institution that calls itself British but which belongs in fact to the world.' Despite occasional self-satisfaction, Professor Linda Colley, the curator, and her colleagues are to be congratulated for bringing these treasures to light from the dust and dimness of the Bush-Blair years.

The title of this exhibit, Taking Liberties, goes back to 1980 and a famous quotation by E.P. Thompson, the social historian and peace activist. ‘For two decades,' he wrote, ‘the state, whether Conservative or Labour administrations, has been taking liberties, and these liberties were once ours.' England had the most reactionary government in Europe he argued, ‘simultaneously attacking the livelihood and democratic rights of its own people.' He referred to spies, data collection, jury vetting, surveillance state, interceptions of mail, tapping of telephones, trolling internet traffic, and police murder. This was the ‘secret state' (as Thompson called it) which looked back to ‘Old Nobodaddy' (as Blake called it) or ‘the Thing' (as Cobbet did) and forward to the world of Closed Circuit Televisions (CCTV), Anti-Social Behaviour Orders (ASBOs) and High Net-Worth Individuals (HNWIs).

In the phrase ‘Taking Liberties' Thompson introduced something powerful, a double entendre mixing state crimes with bad manners. ‘The taking of liberty' transgresses the bounds of propriety. A.A. Milne's children's poem explains:

Excuse me, Your Majesty

For taking of the liberty

But marmalade is tasty if

It's very thickly spread.

‘To go beyond the bounds of civility', yes, that definition pertains to the subject since the advocates of freedom will always seem to be clownish or rude, at least to begin with, their voices too loud, breaking the polite murmur of civil society, or their elbows and knees knocking over the marmalade, jam, honey, and all the breakfast dishes. (Walk Don't Run, children.) The exhibit is firmly within bounds. Its icon is the clenched fist of working class solidarity - ‘one and all, one and all' - rendered here neither in anarchist black nor communist red but in pastel hues of pink or turquoise. The dangerous gesture has given way to an attractive brand.

The phrase catches us, we want to go along with it, but as we think about it, it becomes one of those brain teasers that tugs in opposite directions. As a gerund it does not distinguish subject from object. Is it about attaining liberty or getting rid of it? Lenin summarised the class approach to social analysis by two questions, Who? Whom? Who takes liberty from whom? Thompson and Colley pull the phrase in opposite directions. Thompson says the state takes from the people while Colley says the people take from the state. Hidden in this argument is an academic quarrel going back a few decades.

In a nutshell this is it. In 1963 Thompson published The Making of the English Working Class setting a scholarly agenda with ‘class' in the middle of it. Colley's Britons (1992) put paid to that, placing ‘nationality' in its stead as the central problem of modern British history. Thompson had downplayed women and people of colour. Supported by Harvard, Yale, and Princeton in the US, and by Oxford, Cambridge, and the LSE in England, Britons was an establishment book. Indeed Colley lectured on ‘Britishness' at No.10 to Tony and Cherie Blair as part of the Millenium lectures. Many people took ‘class' as a mark of psychological or biological identity rather than as an economic relationship based on material fact, or as an ideal vector of social equality and true livelihood. Thompson increasingly soured by events, no longer found that such a historical class with such an historic task had much meaning, and, as if the idea of class was merely a perishable commodity on the shelf, he announced that it had passed its sell-by date. As an academic quarrel, the laurels fell to Colley. And yet state surveillance mounts, the wars expand, the prisons increase. After all, she returned to the subject and to the phrase.

Her preoccupations remain the same - the franchise and the vote - and with the political entities comprising, what shall we say? Great Britain, or the UK, or England-Scotland- Wales-and-Northern-Ireland. Whatever. She is fond of the non-political locution, ‘these islands'. There is an exhibit of flags, and the first ideas for the Union Jack in the designs proposed by the Earl of Nottingham under James I. ‘Liberty' entails some of the constituent parts of Britain.

For Thompson the problem of identity was always one of politics, neither gender nor ‘colour'. As he saw it, there were ‘the swaying to-and-fro motions of social class', of privilege and property against liberty and equality. As to identity he expressed a surprising view: ‘Take the jury away and I would face a crisis of identity. I would no longer know who the British people are.' Britishness to him was directly related to democracy: ‘The jury is, I think, the last place in our institutions where the people - any people - take a hand in "administering" themselves.' The jury, to him was both the palladium of liberty and a random equaliser for the future. The jury system is, he wrote, ‘a lingering paradigm of an alternative mode of participatory self-government.' The exhibit alludes once to the jury.

My favourite is the case on the Rights of Man, for here is William Blake's notebook, and his tiny handwriting, with drafts of both London (the harlot's curse, the blood down palace walls) and Tyger! Tyger!, and the tremendous revolutionary human energy released throughout the Atlantic during the 1790s, and with a pencil sketch portraying Tom Paine. In the same case is a spy's report to the Home Office written after following Paine to Dover. One of Gillray's satirical prints depicts Patriotic Regeneration from 1795, as hundreds of delegates with many black faces look on, wearing the bonnet rouge, as the tribune issues out the call to equalise property. Communism and the black faces of successful slave revolt were united in the imaginary of the bourgeois philistine. As absent as the slave revolts is republican Ireland, particularly the United Irish and its revolt of 1798 that directly led to the opposite of a republican independent Ireland, namely the ‘United Kingdom'. Over this case, like a foreboding angel, Opie's beautiful portrait of Mary Wollstonecraft has her in her house cap, with the soft hues and light offsetting those penetrating, deep pooled eyes of acute observation and integrity of vision. Framed in ornate gold, the portrait contrasts with her gravestone only a ten minute walk from the British Library in old St. Pancras church yard where it is covered with moss, velvet to the feel of the passing hand.

The affirmative traditions of radical, socialist, communist and labour politics have vanished. Socialism is not here, communism is an absent ghost, anarchism unmentionable, while heresy is a faint wisp. Big themes and ideas such as Class, Equality and the Commons are missing. Then there are incidents and persons absent such as the Peasant's Revolt of 1381, the English Bibles from Wycliffe to Tyndale, the Geneva Bible. We find John Lilburne but not Gerrard Winstanley whose ideas Locke opposed. Where is Jack Cade? Where is Robert Kett? Tom Paine but not Tom Spence. Charles Dickens but not Charles Marks. When the census taker came knocking at the door of number 28 Dean Street, parish of St. Ann's, Borough of Westminster, and found the German revolutionary exile, Karl Marx, he recorded him as Charles Marks and so, by the official act of surveillance and data collection, inscribed the revolutionary's name in British spelling. Why is he not here, Karl or Charles? He should be.

Karl Marx wrote of the Ten Hours Act (1848),

In place of the pompous catalogue of the ‘inalienable rights of man' comes the modest Magna Carta of a legally limited working day, which shall make clear when the time which the worker sells is ended and when his own begins.

The workers put their heads together and as a class compelled the passing of a law which prevented them from selling themselves and their families into slavery and death. Marx provides numerous footnotes to factory inspectors; it is not only jurists who interpret this Magna Carta. The chapter resolves the central paradox of political economy which can be expressed as follows: How can labour be both a commodity sold at its value and the source of a surplus value greater than it itself is worth? The answer entails the history and the logic of the transition from the commons to the wage. Serfdom arose from the corvée not the other way around.i Part of the land was cultivated in severalty (i.e. private property) and part in common, the ager publicus. Clerical and military dignitaries usurped this land and the labour spent on it. ‘The labour of the free peasants on the common land was transformed into corvée for the thieves of the common land', writes Marx, and from the corvée to the struggle over the length of the working day.

Neither the commons nor equality are themes in this exhibit. Let's think about it for a moment. Can you have liberty without equality? The answer is certainly yes if liberty means liberty of property, then we have rampant privatisation, free trade, inviolable contract. But suppose liberty meant ‘the freedom of just conditions' for which the rebel leader Robert Kett is nobly remembered at Norwich Castle? Or, suppose it meant an end of servility, deference, doffing of caps, tugging of forelocks, curtseying? Then liberty entails access to equal subsistence.

As for the commons, in a corner nook in the darkest part of the exhibit, right after you've passed the plastic box with Magna Carta in it, there is the precious, little known Forest Charter. The display case caption reads:

England's forests had once given the common people somewhere to forage for food and fire wood and space for their animals to feed: the Charter of the Forest restored the tra ditional rights of the people, where the land had once been held in common.

This can light the lamp of history and cast its luminosity into the darkening corners? We have some of the rights in the exhibit and none of the livelihood. There are liberties to be had as the exhibit shows; there is livelihood too which the exhibit does not.

Commoning has been there all along. ‘Commons is become a king', Kett's rebels said in 1549. The fellowship of mutual aid characterising the village community that R.H. Tawney called ‘a little commonwealth' or ‘practical communism'. Woody Guthrie, the Dust Bowl troubadour, ‘When there shall be no want among you, because you'll own everything in common. That's what the Bible says. Common means all of us. This is old Commonism.' In 1941 the Common Wealth Party began to win by-elections with the slogan Common Ownership. It reached its apogee in the Beveridge Report of 1942 with its promise of ‘cradle to the grave' social security. John Wycliffe translated Acts 2:44 as to ‘hadden alle thingis comyn'. The early Christians ‘had all things common [...] as every man his need', a view that entered Marx's definition of communism as, ‘From each according to their ability, to each according to need.' ‘Where is Fair Shares?' the once defining Clause Four of the Labour Party's constitution stated:

To secure for the workers by hand or by brain the full fruits of their industry and the most equitable distribution thereof that may be possible upon the basis of the common ownership of the means of production, distribution and exchange.

It is gone from the Labour Party but why does it have to go from history? No, said Thompson, ‘there is not a tested prototype of a democratic commonwealth anywhere in the world', and yet this has been precisely the conversation among the world's Have Nots since the early 1990s.

The coal miners strike of 1972 reminded Thompson of ‘the egalitarianism of necessity', just as their strike of 1893 reminded William Morris of ‘a condition of practical equality of economical condition amongst the whole population'. The energy workers bring this huge awareness of equality and ‘the intricate reciprocity of human needs and services'. The relationship between liberty and equality, the relationship between class and freedom, stands at the axis of history. The levellers got their name not as a proper noun, a brand name, but as a common noun with lower case letters meaning dis-enclosing, bringing down the walls. An Englishman (Tom Paine again) conveyed the key of the French Bastille with its towering walls to the American George Washington. England awaits its historian of the wall, and it would truly be ‘bottom up history' for was it not Bottom the Weaver who explained to Snout the Tinker how to make a chink in the wall? Well, jokes aside, the theme of livelihood is not taken up. The commons is present in the Forest Charter but the taking of commons is a story untold. Privatisation reigns quietly supreme but behind the scenes so to speak, like the whispering down the corridors of power of the English elite, the classic gentleman's agreement.

The issue seems to be this: I'm casting the exhibit as a reply to E.P. Thompson (largely on account of the title, Taking Liberties), but the issue that's really on the table is the praxis of commoning versus the privatisations of neoliberalism wherein identity politics, particularly, of women and people the colour of the earth, have attained recognition at the expense of class struggle. The wages-for- housework perspective was no less than revolutionary. Third Worldism placed such identities squarely as productive of surplus value, thus changing the notion of the proletariat to those not receiving even the ‘irrational' wage. Neither new sovereign nations nor access to the franchise within the old nation liberate the proletariat any more than President Obama or Secretary of State Hillary Clinton represent victorious avatars of the working class. But what is the notion of the working class? It takes us back to 1963 and Thompson's Making of the English Working Class. Now as then, this notion is a political question of the future, though Thompson saw the future only through the past that he had discovered. Equality has always had a meaning in Britain as ‘a man's a man for a that and a that', but the equality inherent in ‘just conditions' or an equality of material access, in short, an abolition of the division between necessary value and surplus value, awaits its conclusion. Hence, the light which the Forest Charter might throw. The praxis of commoning implies fair shares of the product and fair shares in the work. The end of exploitation requires the expropriation of the expropriator.

Economic rights are present in a section entitled Freedom From Want, an American phrase. It is odd to find it here since Americans like Andy Kopkind, the fine 1960s journalist, fled the USA to England precisely to find socialist discourse, and here is an English woman taking an American phrase to express an idea she durst not express in the idiom of its birth. The phrase was one of the Four Freedoms formulated in the context of the Battle of Britain and enunciated by Franklin Delano Roosevelt in 1941: the freedom of speech, the freedom of religion, the freedom from fear, and the freedom from want. President George W. Bush in October 2001 deliberately omitted these last two ‘freedoms' in his speech on the endless war against terrorism. While Bush was preparing to do as he list, Tony Blair sat in the gallery with a pleasant look on his face, perhaps thinking of marmalade thickly spread. It's good to see the return of the phrase even as part of British liberties.

Image: 'Police and Hussars charging the proclaimed meeting at Ennis: scene in the courtyard'. Image taken from Illustrated London News. Originally published/produced in London, April 21, 1888

A series of The Saturday Evening Post essays in 1943 explained the meanings of the four freedoms. Carlos Bulosan wrote the essay on freedom from want. Born in 1913 in Pangasinan, Philippines, he came to America at the age of 16, and was kicked around from the Alaska canneries to back-bending labour in the San Joaquin valley. He spoke for ‘equal opportunity to serve themselves and each other according to their needs and abilities.' ‘So long as the fruit of our labour is denied us, so long will want manifest itself in a world of slaves.' His essay draws on a poem he had written three years earlier, in 1940:

We are the men and women reading books, searching

In the pages of history for the lost world, the key

To the mystery of living peace, imperishable joy;

We are the factory hands the field hands mill hands everywhere

Moulding creating building structures, forging ahead....

We are the living dream of dead men everywhere,

The unquenchable truth that class-memories create

To stagger the infamous world with prophecies

Of unlimited happiness - a deathless humanity;

We are the living and the dead men everywhere....

If you want to know what we are -

we are REVOLUTION!

While he changed the last word to ‘marching' for the purposes of the 1943 essay, the point remains that power is not relinquished from one class to another without a struggle, nor will we common successfully in the future without a prior and righteous dis-privatisation. Colley wants representative government and a written constitution. Thompson wants to prod the nerve of outrage reactivating the whole libertarian neurological memory system down the centuries. Thompson uses a physician's tendon hammer to knock your knee on the crossed leg, to see whether it is still capable of giving a kick! OK children, time to go, as the Diggers sang, ‘stand up now, stand up now!'

Peter Linebaugh, author of The London Hanged: Crime and Civil Society in the Eighteenth Century (Allen Laine 1991) and the The Magna Carta Manifesto: Liberties and Commons for All (University of California Press, 2008) completed his PhD at the Center for Social History at Warwick with E.P. Thompson

Info

Taking Liberties: The Struggle for Britain's Freedoms and Rights, British Library, London, 31 Oct 2008-1 Mar 2009, http://www.bl.uk/takingliberties

Footnotes

i ‘Corvée is labour, often but not always unpaid, that persons in power have authority to compel their subjects to perform', Wikipedia, http://www.wikipedia.org

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com