Visualising Invisibility

The Arnolfini’s show Port City: On Mobility and Exchange deals with the conflicts between illegal migrants’ need to remain invisible and art’s necessity to reveal what is hidden. Review by Jennifer Thatcher

In a recent lecture at the ICA (26 October) on the futile rhetoric of resistance, Slavoj Zizek criticised the ineffectiveness of political anarchism, the fashionable strategy championed by academics and activists who levy attacks on governments from the sidelines. Such activists, he argues, operate safe in the knowledge that, in the case of anti-war demonstrations for example, their actions will not affect policy, and furthermore that the tedious, bureaucratic business of governing their nation will continue unaffected. On the dirty issue of immigration, Zizek scorned the naivety of a liberal open-door policy, and played up the paradoxical situation of anarchists helping immigrants to gain state-recognised status. But Zizek proposed no miracle solution: if he was defending the principle of democracy and the need to extend political participation and rights to those who are currently unrepresented, he was disdainful of current mainstream representational politics, and particularly Third Way solutions. Nonetheless, it’s not hard to imagine, given his logic, what he might have thought of the touring exhibition on migration initiated by Bristol’s Arnolfini gallery: another attempt to assuage the liberal conscience.

However, if the art gallery remains, in this country at least, a safe ghetto for radical musings on contemporary politics, it is wrong to dismiss all art, and indeed culture for that matter, as entirely frivolous, despite its frequently tokenistic and clumsy attempts to appear concerned. Liam Gillick, in his blog relating to the Memorial to the Iraq War exhibition, also at the ICA earlier this year, pointed to the need for artists, in unacceptably dire political times, to ‘step outside their normal practice’ and make their objections known as citizens foremost. But to separate the responsibilities of creativity from those of citizens does a dangerous disservice to the potentials of art, forcing art to retreat into mere entertainment and severing its link with the world around it. Port City is an ideal case study through which to observe the relationship between the political concerns of artists and their artistic expression.

Gillick does go on, nevertheless, to offer a useful function of art, as a marker and multiplier of differences and as ‘a perfect form for the revelation of paradox’. And artist-curator Ursula Biemann’s major contribution to Port City – in the form of photographs, documentary videos, commissioned film programme and eloquent catalogue essay – persuasively demonstrates the value of presenting different voices. Taking up the whole ground floor gallery at the Arnolfini, her crowded video installation Sahara Chronicle established the Maghreb (Morocco, Algeria, Libya, Tunisia) as the focal point for the exhibition’s exploration of issues surrounding displacement and migration, particularly following the Schengen Agreement that, since the mid-1980s, has sanctioned free movement across most of Europe at the expense of tightening both its borders with North Africa and, as a cruel knock-on effect, dismantling the latter’s own internal ‘open-door’ policy.

Her video interviews map the scale of the migratory network in sub-Saharan Africa: the diverse provenance of those intent on moving ever northwards to Morocco and eventually Europe to seek jobs and fortune for their families; the parasitic entrepreneurs, from the ‘coxer’ or broker who takes commission for arranging migrants’ travel to the next border, to the ‘production manager’ filling out forms and taking fees, and the drivers of the Sahara Transport Company’s monstrous 4x4s with headlamps literally at human head-height. Harrowing interviews with interned clandestines defy any romantic notion of a symbiotic relationship between these self-proclaimed ‘brothers’: these particular migrants gave themselves up to the police following four days’ starvation and dehydration at the hands of their guides. This is bare life.

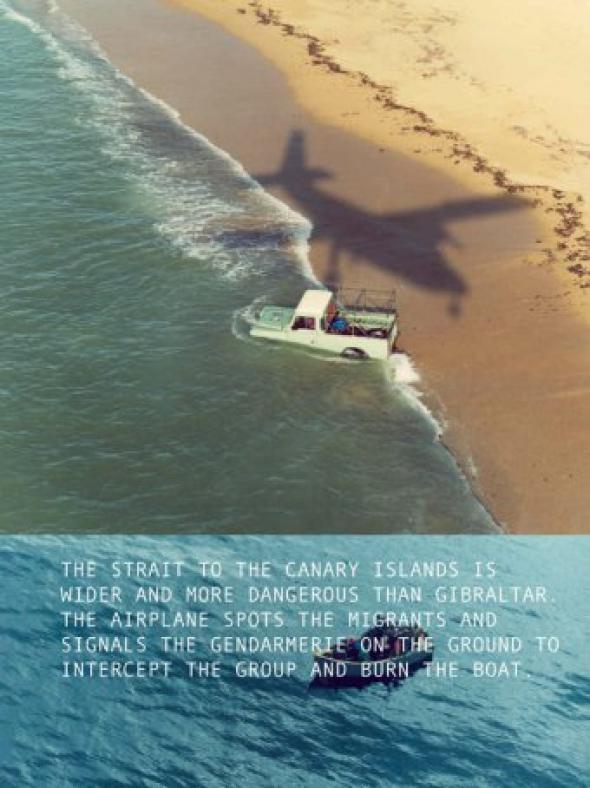

Roving surveillance cameras are the vicarious eyes of the authorities, listlessly watching over the vast Saharan desert for signs of life. The stream-of-consciousness style of much of the footage increases the palpability of the endless waits; the days, even months of being on the road – and, by extension, the sense of hope that seeks to override the very real anticipation of being caught. By contrast, the shorter looped film sequences mirror the cyclical nature of these transactions, whereby the same transport company is employed by the authorities to return unsuccessful migrants as the one which brought them to the border. Biemann describes this approach to filming as ‘sustainable representation’, not simply in opposition to the geological issues of desertification that face the region, but also as a conscious alternative to the ‘targeted shots’ of mainstream news reporting that fix their subjects as stereotypes, denying their potentiality to take on other, less newsworthy roles.

This complex web of relationships between migrant, broker and the authorities underlines the inadequacy of the binary models with which we are usually confronted by the media: victim/perpetrator; legal/illegal. Biemann leaves us in no doubt as to the geo-political roots of this psychical complexity. The brokers are ex-Tuareg rebels, who, returning to their capital Agadez in Niger after the rebellion of the early 1990s, set up the transport business for lack of other employment opportunities; the authorities are able to keep a level of control over this semi-legal operation, aware that it keeps the rebels in a compromised position over their own semi-legal citizenship.

The central Saharan Tuareg territory itself was split between five countries in a colonial agreement in 1884, which has left this nomadic tribe a minority in their host nations. The French built a uranium mine at Arlit in Niger during the Cold War, largely eschewing the Tuareg for their own, foreign workforce; at the end of the Cold War, uranium from the new markets caused prices, and employment numbers, to plummet. The Tuareg, then as now, and like so many native tribes, have lost badly at the hands of the colonialists. Paradoxically, the Tuareg Diaspora has recently grown in importance as the tribe’s knowledge of the terrain and links across borders can be exploited for the clandestine migration business; Biemann describes the Tuareg as the ‘hyphen’ between the poorer Suhal zone (Mali, Chad, Niger) and the Arab North.

Image: From the series Sleepers 1-3, Yto Barada, 2006

While Biemann is sensitive to the moral dilemma in making visible those who necessarily strive to remain invisible, she nonetheless perceives the process of bringing buried truths to light as an important function of contemporary art. Yto Barrada’s voyeuristic suite of black-and-white photographs, Sleepers 1-3, 2006, zoom in on the awkward figures of men sleeping on patches of grass. Lying face down on the ground or covered by a makeshift hood, these men protect their faces against the blinding sun of Tangier, but also from the judgement of our gazes. Their physical anonymity echoes their legal status as the ‘burnt ones’: those who destroy their identity papers and with it the evidence of their past in preparation for the attempted illegal crossing to Spain – tantalisingly beckoning across the Gibraltar Strait. Their mummified stillness is an all-too-real portent of the deadly risks involved in crossing the Strait that Arnolfini director Tom Trevor has called ‘a vast Moroccan cemetery’. Yet these photographs restore a level of dignity to these men: highlighting their plight without compromising their identity. Zineb Sedira likewise dramatises the growing isolation of Algeria from Europe, as the protagonists in her wistful and formally elegant two-screen film Saphir (2006) – a young man and the middle-aged pied-noir owner of a deserted colonial hotel – stare out to sea across the handsome but neglected port of Algiers, with ambiguous expressions that might be variously interpreted as longing, nostalgia and resignation.

Image: Still from Saphir, Zineb Sedira, 2006

The architecture and role of ports is developed in two further films. Charles Heller’s documentary, made on a field trip with Ursula Biemann and part of the Maghreb Connection screening programme curated by her, makes a case study of the new port zone east of Tangier, an ironically named Free Zone cut off from its surrounding area by heavy policing and fortress-like planning design, while paranoid clandestines hide in the nearby hills under constant threat of exposure. As Tom Trevor points out in his catalogue introduction, these new peripheral docks, built in the interests of multinational corporations and globalised trade, are increasingly disassociated from the cultural life of the cities on which they once depended. However, it is instructive to be reminded by Paul Gilroy, in his essay ‘Offshore Humanism’, that off-shore interests have long determined port infrastructure: the fear of theft at London’s West India dock prompted the establishment of the city’s first police force.

Raphael Cuomo and Maria Iorio have set their film on the barren Sicilian island of Lampedusa, the southernmost tip of Europe – closer to Africa than Italy. Sudeuropa, 2006, explores the increased pressures of migration on Europe’s newly fortified outer rim, challenging the view that southern European countries unequivocally want to keep migrants out. A helicopter circles the island’s cliffs, presenting at once an exaggeratedly nostalgic vision of a relatively unspoilt, rugged corner of Europe and the difficulty in patrolling its circumference against the daily clandestine arrivals the authorities desperately try to conceal from the tourists. Yet while the police bemoan the lack of European funding needed to keep up the constant vigil, the film slyly exposes an unspoken paradox. Clips of successful migrants working behind the scenes of the hospitality industry confirm the island’s hypocritical reliance on Africans to support its main economy: tourism.

Image: Still from Sudeuropa, Raphael Cuomo & Maria Iorio, 2006

Image: Still from Sudeuropa, Raphael Cuomo & Maria Iorio, 2006

Other artists in the exhibition have used the very materials of their work to express this precarious relationship between the visible and invisible, and the related dichotomy between permanence and ephemerality. Meschac Gaba has created an architectural model of a fantasy port city – squeezing in iconic buildings from around the globe, such as the Eiffel Tower, the Gherkin and the Taj Mahal, in among clusters of generic warehouses, factories and bridges. Built entirely from sugar, Sweetness, 2006, hovers like a mirage: as seductive as the Hansel and Gretelfairytale. But behind its innocent, pure white façade, sugar conceals a darker history of slavery and exploitation of first the colonies and now ex-colonial, developing countries. If sugar is associated with decadence and decay, William Pope.L’s installation, The Polis or the Garden or Human Nature in Question, 2006, literally enacts the process of entropy. Industrial shelves support tens of onions, some of which have sprouted, others rotted, sometimes falling to the ground to stew in sticky puddles. Painted black and white, these organic lottery balls suggest the random mix of natural and artificial elements involved in our human fate.

With two screens displaying banal shots of contemporary Britain, West Africa and the southern states of America, Mary Evans’ Blighty, Guinea, Dixie, 2007, looks suitably benign at the back of the Arnolfini’s reading room, impressively stocked with photocopied articles from the Economist and specialist magazines, print-outs from the internet and a library of books from the now-mandatory Empire to volumes on Bristol’s slave trade. A telescope standing in front of one screen invites viewers to inspect the grand exterior of a restored American plantation house; but rather than the expected close-up, the viewer is offered a kaleidoscopic spectacle of seemingly unrelated imagery: basket-weaving, a horse in a pasture, the changing of the guard. Gradually, as with all patterns, the brain tries to find links between these three axes of the Atlantic slave trade; Evans again obliquely hints at the history that lies hidden behind the superficial screen of daily images. It’s a tenuous exercise but oddly gripping.

Image: Still from Sudeuropa, Raphael Cuomo & Maria Iorio, 2006

There is nothing subtle, on the other hand, about the style of Erik van Lieshout’s hypnotic video, Lariam, 2001, booming out over all the first-floor installations. Ever the Shakespearean fool, van Lieshout here presents a pastiche of a music-video, in which he and a friend, dressed in the decidedly uncool Dutch uniform of shorts and flipflops, travel to Ghana to make a rap song – in Dutch – about the anti-malarial drug Lariam. A scaled-up, scrappy version of the Roche-branded packaging forms the cinematheque for the film. Following a quick lesson in rap technique with a local guru, the video leads to the surreal climax in which an excited crowd of locals, jumping up and punching the air, join in the chorus – Lariam!

The film itself provides little context for the venture: like the locals we are given no translation of the lyrics – which the catalogue later reveals to be ‘Instances of suicide have been communicated, but a link with Lariam could not be demonstrated’. But the strength of this video, like all Lieshout’s work, is in the odd combination of absurdity and earnestness: a European geek retracing the roots of rap in a former colony apparently to celebrate a Western drug whose side-effects include depression so severe it has been linked with torture, and whose expense renders it inaccessible to all but luxury travellers. Yet what more appropriate metaphors might there be to raise awareness of a dubious drug with side-effects potentially indistinguishable from the symptoms it is supposed to inhibit?

After the epic African journeys that form the backbone of the exhibition’s narrative, the British-based works seemed somewhat trivial. Even Melanie Jackson’s elaborate pop-up diorama of the recent wrecking of MSC Napoli on Devon’s Branscombe beach looked quaintly Famous Five – an impression reinforced by anti-climactic testimonies from bemused locals, rogue scavengers and the sleepy village police. The title of the piece, The Undesirables, 2007, might equally refer to the pesky looters or indeed the mostly worthless or niche-interest bounty that included proportionally more low-value goods (flip-flops, shampoo and dog food) than the prized motorbikes and bottles of vodka. Indeed, if this piece has any resonance outside its local context, it is in bringing to light the unexpectedness of the goods: containerisation has produced a perverse scenario where a ship’s contents – which may include a group of clandestines – is a mystery even to those who transport and unload it. More poignantly, Sarat Maharaj’s brief account of the drowned Chinese cockle pickers at Morecambe Bay, reproduced in the catalogue only, movingly describes the very 21st-century vulnerability of these illegal workers, some of whom had been able to use their mobiles to make a farewell call home to south China, but, with insufficient English and a desperate fear of being deported, not to call for help locally.

Image: Sweetness, Meschac Gaba, 2006

Perhaps fittingly, many of the Bristol-specific works in this leg of the exhibition, mostly commissioned by Milanese curator Claudia Zanfi, were taking place outside the gallery, including an ongoing project by Maria Thereza Alvez to grow seeds unwittingly left by the slave ships along with their discarded ballast – materials such as pebbles used to balance uneven cargo. Nonetheless, there was enough to see at the Arnolfini not to feel cheated as a non-local visitor; with a rolling programme of live art and cinema, there was enough material to make several visits. However, it is difficult to evaluate whether Port City will encourage Bristolians, and later citizens of the other cities on the tour, to review their own upmarket waterfront regeneration – including the Arnolfini – in the context of the city’s role in the Atlantic slave trade.

Port City coincides with the 200th anniversary of the parliamentary abolition of slavery in Britain. The selection of works clearly suggests that the exhibition is not a celebration but rather an uncomfortable reminder that the colonial interests that produced slavery in the first instance continue to reverberate in its contemporary manifestations – whether the cockle pickers or people-traffickers. In this, Port City is deeply cynical: freedom is still contingent on the lack of freedom of others. And if the art here might well succeed in rendering the invisible visible, in fracturing the monoculture of the press, it too often fails in another important function: as a space to imagine, and thus sow the seeds of change, for a more positive vision of human relations.

Jennifer Thatcher is Co-director of Talks at the ICA, and a freelance writer

InfoPort City: On Mobility and Exchange, Arnolfini, Bristol, 15 September – 11 November 2007, then touring to John Hansard Gallery, Southampton; A Foundation, and Bluecoat Art Centre, Liverpool

http://www.arnolfini.org.uk/whatson/exhibition.php?id=35

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com