Good Social/ Bad Social: the Films of Stephan Dillemuth

The films of Stephan Dillemuth trace the changing habitat of artists from modernist bohemia to the culture industry. Through role-play and reflexivity, the film-maker's attraction-repulsion to romantic, modernist ideals of art and society is given compelling form. By Maija Timonen

The three films by Stephan Dillemuth that were screened at London's LUX 28 space in September all take as their starting points phenomena specific to German history. Lichtmenschen im Sumpf der Sonne – Studien zur Lebensreform (Sunpeople in the Slush of the Light – Studies on the Reform of Lifem) (2002) is about a variety of groupings categorised under the heading Lebensreform, or life reform, that were prevalent in turn of the century Germany. The film considers the transposition of these groups’ utopian aspirations into the contemporary idiom of lifestyle choices. Gesetzt nämlich, dies wäre wahr, wäre es damit auch schon wünschenswert? (Assuming then, this would be true, would that make it desirable also?) (1998) is ‘a film about Richard Wagner and his circle’, as its subheading states. Elbsandsteingebirge (Elbe Sandstone Mountains) (1994) considers the position of the German Romantics in relation to the political events of their time, as well as drawing tentative parallels between the commonly ridiculed romantic sensibilities and contemporary formulations of artistic subjectivity. The press release for the screenings stated that this is the first time these films have been available to see with English subtitles, which adds not only to the sense that these are intently ‘German’ films, but framed the screening events as the re-introduction of something dug out from the archives.

Indeed, these films offer new insight into Dillemuth’s more recent works that deal with contemporary art markets and their distinctly post-national character. Of his many collaborations with Nils Norman, the film I’m Short Your House (2007), and the more recent show You Have Been Misinformed (2008), probe the art market's positioning within a broader financial context. The links between art and finance capital that the work unpacks signal in a slightly tentative way a transformative potential the financial crisis could hold for art. Viewed retrospectively, in the context of Dillemuth’s newer works, the ‘Germanness’ of the older films reflects on the transmuted role the local and the national play in a contemporary art context. They are simultaneously brands and markets, acting as veneers behind which global flows of money are hidden. This shift crystallises in the notion of Bohemia, which forms a recurring aspect of Dillemuth and Norman’s collaborations.

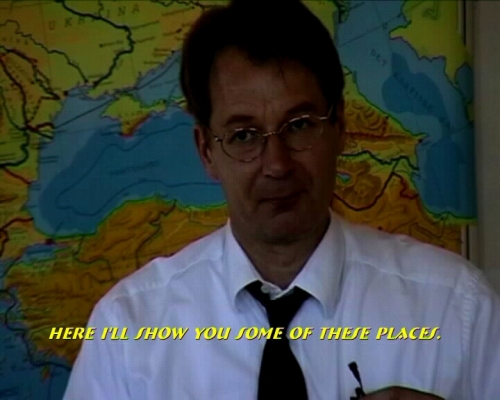

Image: Still from Elbe Sandstone Mountains, 1994

These, and other projects available on Dillemuth’s website, also help locate the films screened at the LUX as part of his broader interest in notions of the public sphere.i The 19th and 20th century ideas of nationality that frame the films are developmental stages in the public's changing configuration from the French Revolution to the present. Dillemuth acts out his contribution to (again very German) debates on the public sphere on a stage set by Oskar Negt and Alexander Kluge.ii His investigations into the shift in the notion of the public sphere are in keeping with a trajectory identified by them: a move from an association with the state to the increasing domination of global corporate interests. If Negt and Kluge were concerned in the 1970s with finding articulations by which a newly fragmented public could have a unified way of conceptualising its resistance, Dillemuth places his focus on the changes commercialisation renders in the function of art.iii His enquiries converge on the role of the artist, and this is something that can be grasped in the works shown at the LUX in which the theme of ‘the artist’ recurs.

In Brecht’s ‘The Messingkauf Dialogues’, the ‘philosopher’ character (standing in for Brecht himself?) says:

Remember that we have met together in a dark period, when men’s behaviour to one another is particularly horrible and the deadly activities of certain groups of certain people are shrouded in an almost impenetrable darkness, so that much thought and much organization is needed if behaviour of a social kind is to be dragged into the light.iv

Dillemuth’s videos seem to take up not only the call to uncover social behaviour that Brecht poses here, but also adopt the third person form in which it is presented. Brecht wrote these reflections on theatre in character(s), and so Dillemuth too uses role-play to engage with history and to produce an understanding of his own position within it. The abundance of content on his website and the density of his films testify to the dedication with which this end is sought, but also to the possible prevalence of means over ends; the viewer/browser can be left with the feeling of entering the centre of a never-ending task of organisation. Indeed, this slight sense of being lost presents itself as a viable object to be engaged with. There is a set of contradictory drives at play. On the one hand the works seem motivated by a genuine desire for social change, on the other, their lampooning often teeters on the brink of nihilism ? it treads a fine line between the ludic and the lurid. The archival nature of the website is consistent with this paradox. It points to the possible persistence of romantic forms of consciousness, and on occasion seems to reproduce the absolutism of an unbridgeable gap between the finite and the infinite. Finding an articulation for the social is here pre-determined by the infinite task of cataloguing and re-cataloguing the reifications and ambiguities it is subject to.

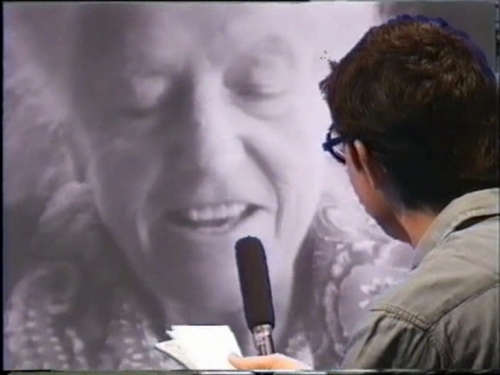

One of the characterisations that surfaces from this multiply signifying word ‘social’ is a courtly form of chattering and clubs, a notion of a cultural elite that finds a contemporary instrumentalised manifestation in the ‘creative industries’. The film about Richard Wagner, in which ‘the artist’ as a political being is explored through his life and associations, takes this up. The far-reaching implications of these courtly forms of sociality and their appropriations culminate in a consideration of his legacy: a mock interview with Winifred Wagner is staged in which she is questioned over her relationship with Hitler.

As much as Brecht's casting of himself as the ‘Philosopher’ in the Messingkauf dialogues could be seen as a confession of his aspirations or a sign of vanity, so the roles of the ‘artist’ and the ‘teacher’ Dillemuth takes on and scrutinises are not devoid of the desire to inhabit them or an enjoyment derived from this. His smirking art teacher in the Lebensreform film ridicules the art academy as a readying of young minds for the market, but the scenes in which this happens are also didactic exercises in themselves. They attempt to make tangible the recurring patterns and commercial implications of art education. The extent to which bohemias of the past can be used to reflect on the way the idea of a creative class has become an instrument of neoliberalism remains undetermined for a good reason. The conditions from which they arose were different to the ones prevalent now, and the conflicts they represented are different from the commercial abstractions they precipitated. This historical gap is negotiated with great complexity in the films, with artistic pains that echo their recurring theme of ‘the artist’. This itself gives rise to a second productive gap. There is an indecision as to whether ‘the artist’ is treated purely as an object of consciousness, or something that has a more experiential dimension.

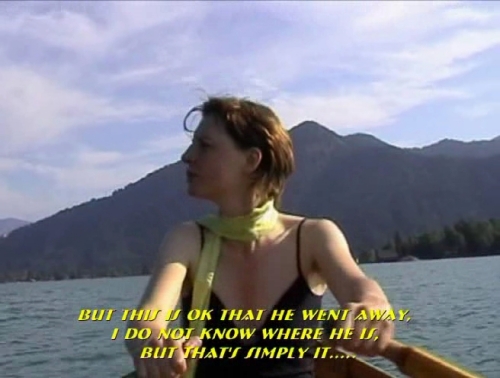

Image: Still from Sunpeople in the Slush of the Light – Studies on the Reform of Life, 2002

In a sequence at the end of Elbsandsteingebirge, Dillemuth himself takes to the mountains of the title. In high scientific spirit of experimentation, he makes attempts to engage with nature, in terms dictated by the romantics, who also lend themselves as the tools of engagement. He starts with standing on a mountain top reading out poems by Hölderlin, moves on to sketch on top of an existing drawing of the basalt rocks customary to the landscape and ends up tripping in the forest, voicing a sense of bewilderment to the camera. As with the romantics being unable to transcend the condition of alienation, they initially attempted to counteract, so too Dillemuth’s heavily mediated play seems here only to reiterate the romantic impasse as a condition of the contemporary artist. The hope for perspectival gain turns momentarily into a sight of a foregone conclusion. It is like the little men in paintings by Caspar David Friedrich, whose figure fails to channel any awe supposedly experienced in the face of magnificent natural phenomena, but who appear more as symbols of their own bureaucratic detachment from the backdrop. The video camera he uses gets personified and then indicted for its complicity in the inadequacy of representation: ‘You don’t know what to focus on, do you?’ he says to it as the auto focus pumps backwards and forwards, and later, when the wonder reaches its peak and the trance music kicks in: ‘I…here…alone in the forest, and what does the stupid camera know about it? Nothing.’ There is an ever so slight sense of resignation in this build-up of mediation that seems to lament an ever more deepened condition of alienation. Even alienation isn’t as integrated as it used to be, it’s been outsourced to the handycam that can be used wilfully and self-consciously as a way of reproducing your ‘own’ alienation.

Formally the films are a combination of improvised acted scenes, clips from films, green screen overlays, hand-held camera work and quotation. Siegfried Kracauer saw cinema as having the redemptive potential of structurally expressing the de-centring of the subject in modernity. Dillemuth’s careful construction of the films, the interplay between the different formal register of the assembled material, achieves a cinematic effect of a similar sort. The marriage of technique and technology manages to produce a structural expression of the ambiguities of the social.

Image: Still from Assuming then, this would be true, would that make it desirable also?, 1998

The point at which this is most palpable is in Lichtmenschen im Sumpf der Sonne and in a scene where a woman (artist) gives an account of having been left by a man who has made the decision to become a bum. She is steeped in the commercial gallery world, he has decided to leave it all behind. Her glamorous outfit caricatures the conformity of her position, but she is not without her flirtations with the ideals that have led her partner to, again, this time metaphorically, take to the mountains. The problems with the rhetoric of co-optation and opting-out that struggle to find expression in other parts of the film come into sharp focus in her reflections. She summarises these by expressing the feeling that many utopian efforts at formulating an alternative way of living simply reproduce the dynamic prevalent in the mainstream world, namely that of ‘women dancing and men pronouncing’. Though the scene itself follows another set of narrative gender conventions, the Homeric roles of man going off on an adventure and woman staying behind in the ‘safe’ realm (quite curiously casting the commercial art world as a contemporary oikos of sorts), they are observed rather than affirmed. It is the way the woman's voice stands out as so sincere and unguarded amidst all the lampooning, while maintaining a reflexive distance from the role she is playing, that is more successful in fulfilling the revelatory function of the Brechtian third person than the play-acting of other characters introduced.v Both the genuinely conflicted nature of the utopian aspirations of the Lebensreform movements as well as the persistence of that conflict in contemporary conceptions of alternative lifestyles come to the fore.

The difference she effects within the structure of the film, the gap between the form her scene takes and the others, acts as a key to figuring the social possibilities of these films at the point of reception. Language plays a central part in making these possibilities legible. Having started speaking her lines in German, she switches halfway through to her native English. This not only signifies her more varied position of reflection, but also makes her seem like an outsider to the socio/formal realm constituted by the film, and through this exclusion, allows her to lead by example. The associative meanings of the film are lent texture by the shift in her relation to it. She expands the scope of the film by offering the viewer a license to partake in the generation of meaning.

Image: Still from Sunpeople in the Slush of the Light – Studies on the Reform of Life, 2002

Adorno took a hesitant step toward formulating an aesthetics of cinema in his essay ‘Transparencies on Film’vi, in which he relents from his earlier condemnation of it. For Adorno, as for Kluge, the social potential of cinema was based on the unconscious, pre-technological character of the experience of watching a film, its similarity to an interior montage. Seen from the perspective of this cinematic imagination, the associative tactics (perhaps still more collage than montage) of the three films, together with this occurrence of difference, could point to a ‘we’ as their constitutive subject.vii

In this, they differ from Dillemuth’s very recent work. Part of the You have been misinformed show was formed by a series of short videos, available on YouTube, in which quotes from newspaper articles on the art market were acted out.viii An interview with Sotheby’s chief executive and a feature on the art investments of a Russian oligarch comprise two of these. These videos take the play-tactics, costumes and quotation also present in the earlier films and turn them on today’s art world in a more direct way. They are funny, but also short, detached and weapon like. They appear summarily aimed at an audience rather than attempting to be inclusive of one. The formal awareness of a possible cinematic mode of reception, present in the earlier films, is in these works exchanged for a self-consciousness of the means of dissemination. It is as if the Klugian utopia of cinema as a potential, ‘Gegenöffentlichkeit’,ix is exchanged for a mockery of the internet (in the form of the commercialised YouTube), for its failure to facilitate one. At least on a gestural level, what is echoed are the aspirations of the masses posting their externalised cinematic imaginations that more often than not remain without an audience. The snippet-like brevity of the videos paired with their apparently speedy production lends them a sense of urgency that presses the importance of their subject-matter, but also an off-handedness that could be read as disposability, simultaneously signalling ‘Something must be done!’ and ‘Nothing can be done’.

Maija Timonen <maijatimonen AT gmail.com> is a writer and filmmaker based in London. She has recently completed a short film loosely based on Bertolt Brecht's Flüchtlingsgespräche (Conversations in Exile) entitled The Debtors

Info

Stephan Dillemuth's selected films were screened at Lux 28 between September 18th and 28th 2008 [http://lux28.org.uk]

Stephan Dillemuth’s work can be viewed at www.societyofcontrol.com

Footnotes

iiOskar Negt and Alexander Kluge, Public Sphere and Experience: Toward an Analysis of the Bourgeois and Proletarian Public Sphere, translated by Peter Labanyi, Jamie Owen Daniel, and Assenka Oksiloff, Minneapolis and London, University of Minnesota Press, c1993.

iii For more see: http://www.societyofcontrol.com/research/start.htm

iv Brecht, Bertolt, The Messingkauf Dialogues, trans. John Willett, London, Eyre Methuen, 1965, p.42.

v For a take on this, see: Jameson, Fredric, Brecht and Method, London and New York, Verso, 1998, pp.51-66.

vi Adorno, Theodor, ‘Transparencies on Film’, New German Critique, No. 24/25, autumn 1981/winter 1982, pp.199-205.

vii Kluge, Alexander, ‘On Film and the Public Sphere’, New German Critique, No. 24/25, autumn 1981/winter 1982, pp.206-220, p.209

viii See: http://www.societyofcontrol.com/dillemuth/2008_spaulings/main.htm

ix ‘Gegenöffentlichkeit’ or ‘counterpublic’ was Negt and Kluge’s formulation for an experientially grounded notion of the public, which stands in opposition to both the bourgeois and corporate public spheres.

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com