Towards an Apotropaic Avant-Garde

This review of T.J. Clark’s 2013 book Picasso and Truth: From Cubism to Guernica first appeared on the website The Claudius App in 2014. It is republished here on the occasion of Clark’s newest volume, Heaven on Earth: Painting and the Life to Come (Thames & Hudson, 2018). In this long review-article, Daniel Spaulding describes the trajectory of Clark’s overall project, and suggests ways to divert the author’s melancholic view of modernity to radical ends.

Is it possible to be a Nietzschean consumed by loss? I doubt it, but perhaps it’s better to try than to be a Nietzschean otherwise. This is one of the points I take from T.J. Clark’s Picasso and Truth, a book that speaks from dead worlds. The major world at stake here is modernism. We seem to glimpse it only in its agonies, though: granted, these may have begun right at the beginning.[1] Clark has drawn out modernism’s perishing, almost single-handedly, it has sometimes felt, for over fifteen years now, that is, since the publication of his monumental Farewell to an Idea: Episodes from a History of Modernism, in 1999. The arguments in this more recent book are substantially the same, might almost be repetitive in fact, even if the author’s emphasis has shifted slightly from knocking out his adversary to holding it on the ropes: Clark now aims, he says, “to keep a kind of resentment at modernism alive, in order to keep modernism alive.” Yet it emphatically isn’t alive: the modernist past, he already said in Farewell, is “our antiquity”; “a ruin, the logic of whose architecture we do not remotely grasp.” Or, more extravagantly, “a world, and a vision of history, more lost to us than Uxmal or Annaradapurah or Neuilly-en-Donjon.”[2] Deader than a doornail. And not. As recently as 2011, Clark exulted at having “caught this last intransigence of modernism on the wing” at a Pierre Boulez concert (he does not say in what direction that odd bird might have been flying).[3] This was a couple days before he would again savor something of the like in the German painter Gerhard Richter’s large retrospective at the Tate. Another pair of late, latest, last moderns for the canon. Going, going, never gone.

Likewise Pablo Picasso. In Picasso and Truth, he’s a revenant. Mediocre writing trails him (Clark makes sure to emphasize the badness of the literature). But it can’t finish him off. He appears in both this book and Farewell to an Idea as a figure almost too awful to be looked in the face. He leaves behind reaction formations or dumb biographical kitsch; criticism fails his work as it failed Edouard Manet’s Olympia in 1865.[4] But failure is Clark’s toehold, as often before. Modernism to him is a willful or sometimes reluctant refusal to make sense, or else a frantic attempt to make sense otherwise; it continually circles “back and back to the black square, the hardly differentiated field of sound, the infinitely flimsy skein of spectral color, speech stuttering and petering out into etceteras or excuses.” (This is from Clark’s 1982 article on “Clement Greenberg’s Theory of Art”).[5] And it does so because of its “lack of grounding in some (any) specific practice of representation, which would be linked in turn to other social practices – embedded in them, constrained by them.” Modernism negates. It does not, in general, latch onto a totalizing practice that could make its cancellations more than merely negative, by drawing them into a new ensemble of signs. This is why modernism failed to build the new worlds it so ardently imagined. Hence also Clark’s unexpected opening gesture in Picasso and Truth: a sympathetic citation of Philip Larkin, of all people, nominating “Pound, Parker, Picasso” as “twentieth-century destroyers – those who had tried to rob him of the joys of Sydney Bechet and the consolations of Thomas Hardy.” Alarm bells ought to be going off already.

There will be more to say about the idiosyncrasies of this concept of modernism. Note first that, in it, failure cuts across both art and politics. Indeed their mutually imbricated disasters have been nearly the exclusive topic of Clark’s art history ever since his first two books, Image of the People and The Absolute Bourgeois, both published in 1973. These were paired studies of the aftermath of the 1848 revolution in France, written in the aftermath of 1968, one could say in the parallax of two utopias that weren’t. The theme has carried through his subsequent writings. The Painting of Modern Life, 1984, tracked Manet and the Impressionists via their ambivalent response to Baron Haussmann’s reconstructed Paris. Clark was here concerned with the artists’ attempts to get the new city into pictorial form by hook or by crook, and above all by means of a jury-rigged myth of something called “modernity.” Farewell to an Idea, in turn, is explicitly a response to 1989 and the Fall of the Wall. It is an account not quite settled with certain myths of socialism and modern art alike (their entanglement, opposition, and sometime solidarity). Art’s debacle in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Clark here argues (it is in many ways a continuation of the points in his previous books, though with a melancholy twist), was its inability to connect with a positive left politics, or to do so only under the most horrific of circumstances – Jacobinism in 1793, or Soviet state-building in the desperate days of War Communism. But this was equally the failure of the workers’ movement to be more than a dreary inversion of capital’s own modernizing terror, and hence to be equal to modernist art’s best impulses. (I am of course simplifying a far more complicated argument).

The Sight of Death, from 2006, on two pictures by the seventeenth-century artist Nicolas Poussin, is a possible outlier in the sequence. Even this book, though, is to some degree a product of the global left’s resounding failure to prevent the invasion of Iraq, or to manage a persuasive response to September 11. The Sight of Death also marks a shift to what I’m inclined to call a politics of mortality, or, less dramatically, finitude – arguably a conservative proposition, but a politics nevertheless: art as a model of being-in-the-world offered up against spectacle and imperialist war.[6]

The stakes of Clark’s art history are always political, then, and his horizon is always the present. Modernism matters to him because we have yet to escape it, not because it possesses some inexplicable charisma. More pertinently, we have yet to escape modernity itself. Like few others in his discipline, Clark maintains a running dialog between historical investigation and political commentary. In recent years this has evidently come at the cost of an increasingly wearying glumness – hard to begrudge, given the current state of things.[7] Such matters are relevant here: I am concerned in this review to consider Clark’s politics and his art history together, to offer an interpretation of the project as whole on the occasion this most recent book (which I should perhaps first say does not strike me as his most important intervention). His is an immensely rich body of work, so it will be impossible to generalize. As a rule of thumb, though, let’s postulate the following: in Clark’s writing from at least the past decade and a half, modernism is a failure, socialism is a failure, and they are both failures even to fail because they still continue their dance of death in the default of something better and genuinely postmodern, something that would put their unhappy spirits to rest by being what they always should have been. The new book is cut from the same cloth. Picasso is a problem because modernism is a problem.

…

Yet more than perhaps ever before it is unclear what, concretely, Clark’s postmortem is meant to accomplish. Farewell to an Idea was in the last instance a rearguard action in the interval between the collapse of socialism and the faint prospect of its revival. (This is the book’s last line: “The present is purgatory, not a permanent travesty of heaven.” Well, don’t be so sure.) Even this hard hope seems distant now: distant in Picasso and Truth, distant in reality. The uprisings of 2011 produced no rebirth of the left. Instead their bad sublation has lingered in the streets of Cairo and Kiev, and in the ruins of Syria. Modernism hardly seems a factor here. So if it isn’t quite dead, yet anything but thriving, and also yet to be rightly put to rest, what is modernism nonetheless supposed to do for Clark, or for us, in a project like this, a book about the art of Pablo Picasso in the forty years before World War II?

I’m not sure I know. My best guess is that it’s supposed to regret itself. For Clark, modernism at its most compelling oddly comes to look like an example of what modernism wasn’t: the negative image of its own unachieved negation. Moreover it appears that the lack of a different modernism was to some degree contingent. “[I]t could have been otherwise,” Clark writes. “It ought to have been otherwise. And this is not a judgment brought to the period’s masterpieces from outside […] but the judgment of the masterpieces on themselves.”[8] So: what wasn’t modernism and why wasn’t it that? It wasn’t Nietzschean, for one thing. Modernism failed to become the lie that Nietzsche wanted art to be. It was not, except in rare instances, on the side of Bizet instead of Wagner. Nor is it clear that it could or ought to have been. Picasso and Truth may express an argument that Clark is having with himself about what the “otherwise” could mean. This equivocation is also – Clark convinces me – part of the art itself. Picasso’s pictures never fully broke with the meat-and-potatoes of the bourgeois nineteenth century – its particular realism, its sense for interiors, its commitment to nearness and experience: a whole complex of qualities that Clark sometimes gathers under the notion of “room-space.” It instead culminated in the inferno that is Guernica. A picture as far from Mediterranean lightness as it is from early Cubism’s Gemütlichkeit.

Picasso’s oeuvre is the elegy of an untruth that never was. History barred the exit. Picasso and Truth aims to show how.

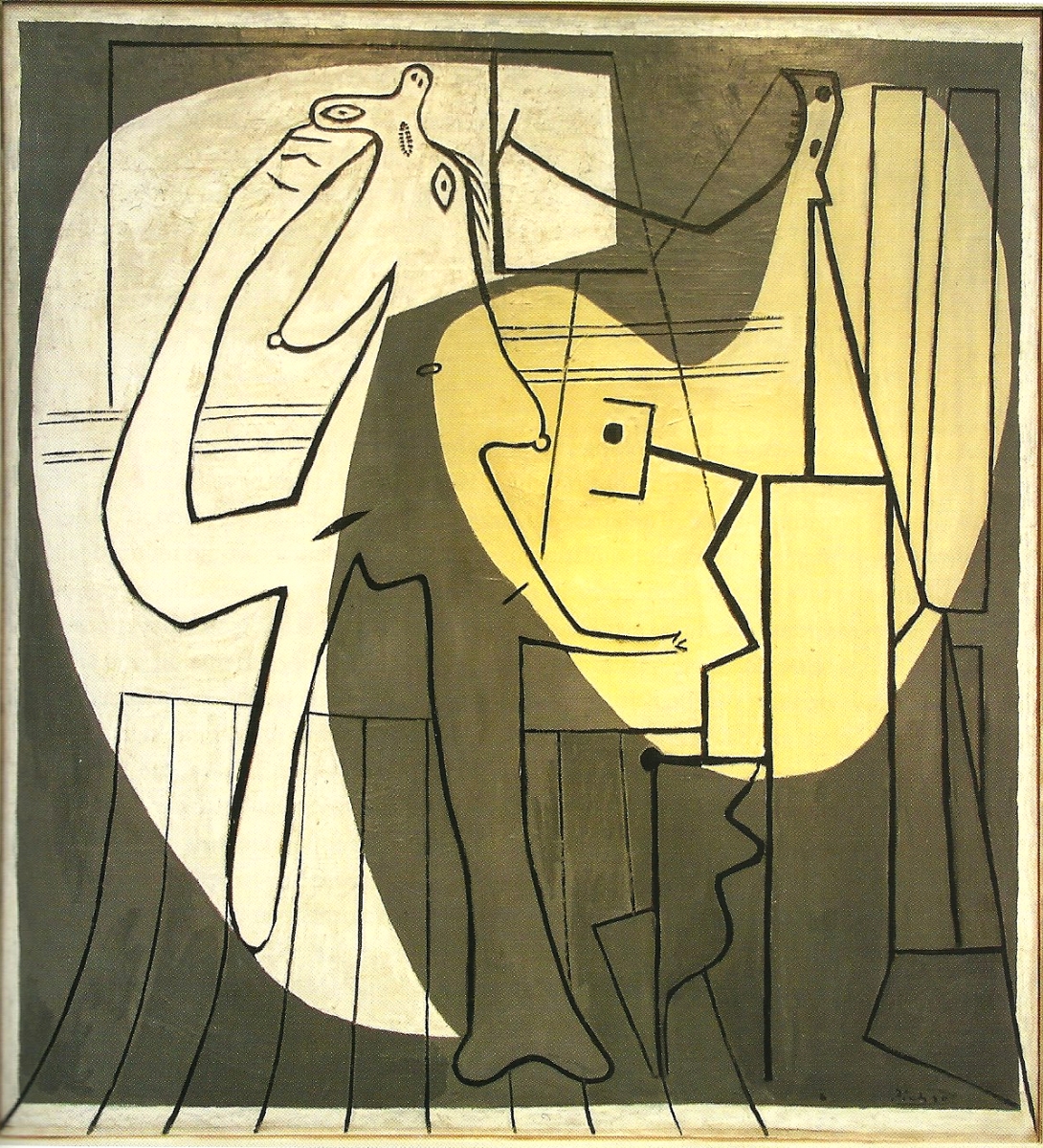

Picasso, Three Dancers, 1925

The book is organized into six chapters, originally lectures, the first four of which each gravitate around a single painting: The Blue Room, 1901 (treated more hastily than the others, because the chapter is basically concerned to introduce the terms of the book’s argument as a whole); Guitar and Mandolin on a Table, 1924; Three Dancers, 1925; and The Painter and His Model, 1927. The fifth chapter deals with a number of figure paintings from the later 1920s and early 30s; the sixth and last is about Guernica, 1937. This is a strong but in some ways counterintuitive choice of objects. Most noticeably, it does not focus on the classic period between the Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907) and the years immediately after the First World War – that is, the period of high Cubism. Works from those years are mostly brought on to illuminate some point being made more fully about a picture from after 1920. In part this is because the author already dealt with Cubism at length in a chapter of Farewell to an Idea: his judgment on that moment, in a nutshell, is that it imagined the look of a new pictorial language without being that language, and as such epitomized modernism as a whole. (See above in re: failure.) But this is inadequate motivation. Clark’s chosen pictures belong to phases of his career that the most influential of Picasso’s recent interpreters, notably the art historians Rosalind Krauss and Yve-Alain Bois, would date either prior to the artist’s properly semiological breakthrough – his supposed discovery of the arbitrary nature of the relation between signifier and signified – around 1912, or else after his return to traditional draftsmanship a few years later.[9] And indeed it’s a curious fact that Clark nowhere, here or in his earlier chapter, demonstrates much interest in collage, papier collé, or assembled sculpture, all of which emerged in the years of Clark’s gap and which by many accounts constitute the artist’s most significant contributions to the repertoire of modernism.[10] Clark likes paintings. Not merely paintings, though, but paintings that evince a distinctly more atavistic set of preoccupations than the arbitrariness of the sign: Clark’s Picasso is interested in the space of the tabletop; the bourgeois interior; the weight and eroticism of bodies.[11]

The descriptive passages in Picasso and Truth are ravishing, but their effect is lost in summary. I won’t attempt to reproduce any of Clark’s readings. Instead I’ll say something about the shape of the argument as a whole.

…

Picasso, The Blue Room, 1901

Clark begins Chapter 1 with The Blue Room, a small, early painting at the Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C. It stands for everything the rest of the book will show to us under mortal threat. Picasso’s world, Clark argues, was initially and most profoundly one of small, close pleasures: bodies and things in a room, in “room-space,” a space of belonging. This world was besieged almost from the start. The twentieth century, as Picasso paints it, means the destruction of room-space. The world wars accelerated the attack, but in fact it never let up: it was as good as synonymous with modernization itself. Cubism is the style that most profoundly instantiated room-space, because it stood on the verge of its collapse. Cubism is not, for Clark, the scandal it seemed to contemporaries. It’s rather a species of pictorial nostalgia. His claims are eminently disputable, of course, but readers will get nowhere with the book unless we take them in stride. Concede the following, then:

Cubism […] is a style directed to a present understood primarily in relation to a past: it is a modest, decent, and touching appraisal of one moment in history, as opposed to a whirling glimpse into a world-historical present-becoming-future. It is commemorative. Its true power derives not from its modernity, that is, if we mean by this a reaching toward an otherness ahead in time, but from its profound belonging to a modernity that was passing away: the long modernity of the nineteenth century.

And: “Cubism was the last of the great succession of pictorial styles in Europe premised on the belief that art could only renew itself by a fresh, more basic and comprehensive attention to the form of the world in the eye.”

Because Clark conceives Cubism in this way it quickly becomes a lost object. Pictures such as the large tabletop still-lifes of the mid-20s (works that some have been happy to see as little more than concessions to the market), or the dubiously humanoid figures that proliferate a few years later, bear witness to the process of dissolution, even as they resist it. Bodies henceforth are severed from their belonging to interiors. Interiors are inundated by strangeness and death. Clark spends much of his book describing pictures from a phase of Picasso’s career that is often called Surrealist, though perhaps misleadingly. I agree with the author that they are more accurately seen as instances of late Cubist language under duress. Clark’s point is that the personages and the spatial surroundings in these works are not made weird for the sake of weird (he seems to think that Surrealism proper does do this to its objects, and not much more), but are rather contorted for the sake of preserving a sense of what bodies or rooms might be at all, at a time when everything conspired to tear them to bits.

Picasso’s straining to get “more of the stuff of the world” into his art is reflexively doubled in Clark’s prose.[12] In the text, a whole arsenal of figurative language helps to articulate the way Picasso’s works find equivalents – metaphors – for kinds of experience, though the experiences are not always unambiguously ours; not even necessarily human. “Metaphor” and “experience” have long been great terms in Clark’s art history. Metaphors motivate the material procedures of art by linking a given mark to something else in the world, or in the world of thought. Experience grounds art in something more intractable and testable than the myth of its self-sufficiency. Pictures, or Picasso’s at least, are a variety of ontological proposition. Clark often suggests that they are statements of the form “What would it be like if…?” And this is a way not only to escape into dreamlands but also to think about the real world. Over the course of the book, Picasso’s art comes across as an immensely varied yet rigorous phenomenological investigation of the things that were closest to the artist, physically and affectively. This keeps the link to experience real: it prevents Picasso’s art from escaping into a reified autonomy of the “flimsy skein of color” variety.

For the same reason Picasso’s art is importantly anti-avant-gardist, as much as he was, for a time, undoubtedly part of the avant-garde. This is not so much a matter of abstraction versus figuration (Picasso happened to be a partisan of the latter) as it reflects a commitment to the mediation of lived experience in the process of painting. Everything important happens, for Clark, in the artist’s negotiations with materials and procedures. Modernism was a series of bets on the chance of making its new procedures stick. If it was not to fall back into academicism, or lose its grip on the real altogether – the fate of many of the more programmatic avant-gardist practices – it had to convey some plausible sense of what the world was really like. It needed a will-to-truth. In Picasso’s century, this evidently meant that art had to convey the great fact of the age: the death of nineteenth-century bourgeois culture, the death of room-space.

…

All of which is by way of raising the issue of “truth.” The word is enshrined in Clark’s title. What does it mean? Clark underscores Picasso’s passion for exactitude: “Representations are true or false, accurate or evasive.” On one level this means truth as correspondence, but more interestingly it means the truth of a picture being a world to begin with, one that seems to be habitable even if bizarre, to bear a relation with things we have known or felt, and which convinces its viewers that it would exist even without us. Essentially this is a matter of relating objects to space. Clark also proposes the terms “substance” and “structure.” Or: “Heavy opacity; weightless translucence.” The balance is meant to grant things their specificity while linking them, drawing them together into a whole. Of all Picasso’s styles, his Cubism of the 1910s was most vehemently pledged to this kind of truth. Space and object, structure and substance, interpenetrated endlessly; each belonged to the other, though in no way that had been imagined before. Its bottles and newspapers and pipes wanted to be solid even when dissolving into the grid; they forever dwelt in the shallow space between absolute flatness and indefinite recession. The style Picasso developed together with Georges Braque had the purpose of demonstrating that the two artists had in fact solved the problem of depicting the world in a manner both entirely unprecedented and irrefutable. By the sheer intensity of its means, Cubism meant to certify that its language had a grasp on the real. “Either the painting was rooted in a particular lived experience of space, and offered itself as an analogue – a specific modeling – of that experience and its limits, or it was nothing in particular,” Clark says.

But the paintings of the 20s are for the most part different. They no longer make truth-claims in the same way. They approach, instead, the ambiance of Friedrich Nietzsche – his disdain for exactly the kind of truth that Picasso grappled with so intently. Such an art approaches the need “to recognize itself as pure device.” Clark says the following of the Guggenheim’s Guitar and Mandolin on a Table: “It is the world as it might be, or ought to be, if everything had its being, and derived its energy and specificity, from its becoming fully an aesthetic phenomenon.” Not, then, from its reliance on something felt to correspond with real instances of experience. The picture’s prodigal arabesques have no such basis; its shapes are not for us anymore, as Clark will put it. Suddenly truth and falsehood no longer constitute the proper binary at all. We have passed beyond such things. Or not, because even in Guitar and Mandolin on a Table Picasso is also still concerned to propose art as attached to reality, as a model or analogy for something we know, or could know, out there in reality.

Room-space is still at issue: the painting tests whether it can survive exposure to the open window. The picture-within-a-picture between the table’s legs is, for Clark, an emblem of that function of art-making. So the question is not really decidable. It invariably coalesces, though, around the problem of the destruction room-space. The Nietzschean mode of art could have made its loss more than only loss.

…

Picasso, Guitar and Mandolin on a Table, 1924

Most of what I have just described happens in the first chapter of Picasso and Truth. (Guitar and Mandolin also gets a longer treatment in Chapter 2.) It all unfolds quickly and with characteristic high drama. The following chapters offer variations on the theme. I am sure that Clark’s notion of “truth” gets close to the core of what Picasso was doing, and felt that he was doing. “Room-space” is a great coinage. The same qualities could have been described otherwise, of course.[13] But at any rate it seems evident that Picasso was much more concerned with the weight and density of real things, the proportions of real spaces, than with the arbitrariness of signifiers. Picasso and Truth does more to show how this plays out, pictorially, than any other account of Picasso’s work that I’m aware of. I’m less sure that Clark’s promotion of Nietzsche to the opposite pole carries as much weight as it should. Certainly Clark is in no way properly Nietzschean himself. He does believe in truth. Or at least, he is anxious about its loss. Nietzsche is the name of a desire, the fulfillment of which is not to be willed unequivocally. Partly, it must be Clark’s desire to escape from himself.

We have seen that Clark’s insistence on coherent experience, which is also to say on truth, is not unique to this book. It was for a time central to his notion of what a genuinely political modernism could have been. Modernism could have had a relation to classed experiences of modernity and thereby entered into an alliance with radical practice – practice that would test its truth precisely against its attempts to remake reality. Of course what is at stake here is something different from the coziness of room-space, but it isn’t unrelated: a politics that could take the nearness of everyday life as its keynote was mostly what modernism failed to achieve. Picasso likewise did not go do down that route. There was no Socialist Cubism.[14] But that potential is in some way implied in what Clark understands Cubism to have been – specifically, what it did with the space it inherited from the previous century’s bourgeois order, and sought to defend. In an analogous way, socialism aimed to take over and exceed what bourgeois civilization had built. Marxism failed, Clark seems to think, in large part because it instead became a “grisly secular messianism,” to use a phrase from Farewell to an Idea. Clark does not explicitly make this connection himself, but I think it is legitimate to read it into Picasso and Truth on the evidence of themes developed in the author’s previous work.

Nietzsche signifies, at least in part, a farewell to all that. A farewell to Cubism, too. “Part of what makes the achievement of his high Cubism so irresistible, in the sternest canvases of 1910 and 1911, is the way they seem to add up to a last effort in art at truth-telling – at a deep and complete and difficult encounter with things as they are,” Clark says. The Dionysian works of the 1920s, such as The Three Dancers, are by contrast no longer ascetic and truthful, but rather awful in their Untruth: “the terror has to do with the world they show being unbelievable – counterfactual – but nonetheless (one is tempted to say, therefore) unavoidable, inhabitable, apt.”

And with this we seem to discover an unexpected short circuit in the logic of modernism itself. Because if such a world is untrue yet inhabitable, what does that do to the binary between Cubism’s sense of interior (bourgeois) space and, say, Mondrian’s inviolable abstractions, or Fernand Léger’s world in which “objects have finally disappeared into their commodity form” (as Clark notes of the artist’s 1927 Composition with Hand and Hats in the Pompidou)? It seems to offer a way out.

Nietzsche stands, then, for a third option. A Nietzschean art would be exterior to the polarization we have seen a younger T.J. Clark propose, in “Clement Greenberg’s Theory of Art,” between an art founded in experience or the “stuff of world,” which would be somehow though not naively realist, and on the other hand a negative, Alexandrian modernism of “speech stuttering and petering out.” It would instead affirm the real world as something that exceeds full comprehension or control (something terrible, something that merely appears to us without being for us). This, it seems, is why Nietzsche figures in Picasso and Truth. Yet Nietzsche is in no way a deus ex machina. Full surrender to Untruth is not really an option, because it would have meant, for Picasso, abandonment of his deepest commitments (one gathers that in modified form they are Clark’s commitments, too). And there were historical reasons, political reasons, why it could not really be a solution, either.

So, to resume. Untruth is the “outside,” but it isn’t depth or recession: it is surface appearance that ruthlessly flattens even the narrow zone of a tabletop (as such it’s also another way to redescribe the archetypal “modernist flatness” that Greenberg, for one, tried to narrate in formalist terms). It negates the fiction of the picture plane’s transparency. It is not-room, not-interior: everything that exceeds and breaks down human possession of a space. Three Dancers opens itself to this new outside, and its figures are consequently made dreadful. The monumental “Surrealist” figures of the late 20s and early 30s then plunge into monstrosity: monstrosity is “the Untruth – the strangeness and extremity – inherent in everyday life,” inherent to those experiences of the body that most readily lead to self-loss – sex for instance. Truth, in turn, resists; it joins battle on the side of room-space, Untruth on the side of its dissolution and a new openness to the world’s unmasterable wild. They are at war and need each other in order to be at war. Their tension was productive for Picasso’s art. It even made for a kind of ethics. But what was in reality coming from the outside was not the sunshine of the Midi. It was a far more sinister light. Picasso was a destroyer but not a happy one.

…

Picasso, The Painter and his Model, 1927

Clark discusses a great number of pictures in Picasso and Truth. The readings are compelling, on the whole; it would take a much longer review to pick out disagreements one by one, or even to register the many sub-arguments packed into each chapter. So instead I will skip to the climax.

Guernica is almost inevitably the destination of Clark’s book. The preceding chapters build to what I have called, with reference to The Sight of Death, a politics of mortality. They assemble, from Nietzsche and Wittgenstein, among others, an attitude towards Picasso’s art that sees it making space for the monstrous and unmasterable, which are equally within us and in the world beyond. (Personally, I prefer the sections that give Nietzsche a rest. The chapter on the 1927 Painter and Model in Tehran is by contrast steeped in psychoanalysis, and probably better for it.)[15] Room-space is the elastic mechanism by which wildness could be “drawn into a totality,” made into a picture. There may be reason for the reader’s skepticism at this point. Truth and Untruth duke it out in the drawing room – there is something still very nineteenth-century about all this portentousness. Guernica, though, pulls us straight back to its own time.

As is well known, Luftwaffe bombers destroyed the Basque city from which the work takes its name on April 26, 1937. Picasso began painting his immense mural a few days later and finished in early June; it was exhibited in the pavilion of the Spanish Republic at the Paris International Exhibition in July. Clark, first of all, thinks that Guernica is a success – this is not always taken for granted. All the more remarkable, then, that its making forced Picasso to confront a sort of death that room-space couldn’t handle. “Some kinds of death,” Clark writes, “have nothing to do with the human as Picasso conceives it – they possess no form as they take place, they come from nowhere, time never touches them, they do not even have the look of doom.” Such is death by aerial bombardment. Modern death. Yet, Guernica “finds a way to propose this, visually.” How?[16]

Clark traces the many intermediate stages that led up to the painting as we see it now. It will come as no surprise that he presents the story of Guernica as the genealogy of its space. Over the previous decade, Picasso had tried to paint himself out of the impasse in late Cubist grammar that came to a head around 1927, the moment of the Tehran Painter and Model. After the “monsters,” though, came the “monuments,” which occupy Clark for a chapter. (The Met’s Woman Standing by the Sea, 1931, is his crucial example.) These paintings give his figures room outside of room-space. The artist puts them on the beach, or in other places that nudge them towards the open; at the same time, they remain (or become) alone, inaccessible, extreme: “They are us, but in our essential non-humanness,” that is to say in moments when bodily composure is still an open question (sex again; death, too; but also our more usual states of unconscious corporeal strangeness). As such they instantiate a new relation between bodies and the Outside, if a brittle one. The comparatively lackluster products that dominate the remainder of the 30s – mythologies and bullfights and the like – wrestle with the same problem. Their one definite achievement, Clark indicates, was to invent a kind of space that was simultaneously interior/architecture and exterior/landscape. It was also importantly a space of agony, death.

This is the immediate context of Guernica, aesthetically speaking. The new work put everything the artist had done before in question. The painting was, Clark argues, too much of everything for Picasso: too big, too public, too much beholden to the violent contingency of current events, to be at all congenial to Cubist room-space, or even the world of the monsters and the monuments. Modern war threatened to destroy the possibility of “world” altogether. The struggle to make a mural out of this – to make something immense and not have it register as sheer dissipation of energy – was thus oddly a struggle to miniaturize its rhetoric: Guernica “is a picture that makes its giant size… work to confirm a wholly earthbound, and essentially modest, view of life.” The work is indeed a history painting of vast ambition. But what concerns it is not a concrete political position, not even a (direct) indictment of something nameable as “fascism.” What was at stake instead was the very survival of a form of life: life as it had been presented in Picasso’s art of the previous decade; life such as had passed through Cubism’s trials and reached some tense equilibrium between room-space and the outside, Truth and Untruth, coziness and terror. Monstrosity was exactly not the solution to this. Neither was melodrama. It was necessary to avoid turning Guernica into Grand Guignol. The successive states of the painting, preserved in photographs by Dora Maar (Picasso and Truth reproduces several), eventually succeed in this: they escape the orbit of the artist’s sex-and-death theatrics. Spatially, too, the work prevails. The picture’s setting may be inside or outside – hard to tell; more likely it wants to be both at once – but this does not make the space vague: on the contrary, Clark thinks it is wholly resolved. The space is grounded, real, but it also pegs everything to the surface and unifies the picture’s lateral spread. The effect is one of “proximity but not intimacy,” or “flatness finding its feet,” as Clark puts it. The grid on the floor is one of the last things Picasso painted in.

Clark thinks the world the final painting imagines is terrible but ultimately both creaturely and deeply human. In it, people and animals are still able to stand on a common ground plane, though Picasso has no illusions that suffering binds them into a community (at an early stage he decided to nix the fallen warrior’s raised fist: a too-literal sign of defiance). The painting’s personae live and die alone. At least they do so in a real space.

It may seem odd that Clark, the “socialist atheist” (as he still calls himself here), does not expend many words on the role of the left in the dire politics of the moment. But then, by now, it may not seem odd at all. He is not much concerned with how Picasso’s picture did or didn’t serve the Spanish Republic’s cause; this isn’t his criterion for its success. The chapter’s politics are more fundamental – ontological, even.[17] Guernica defends a kind of life that Clark values; it does so in the worst possible circumstances. It provides a space in which that life can suffer in dignity. That is evidently sufficient.

…

[Picasso, Guernica, 1937]

There is something dissatisfying about the Guernica chapter. It’s hard to know whether to blame the author or the painting itself. More than anywhere in the book, Clark leans on art historical comparisons: Goya, David, Delacroix, late-Roman sarcophagi. This at times feels like grasping at straws for some way to say what the picture is, since we have no comparable works – ambitious modernist history paintings – that remotely stand up to Picasso’s. Clark is reduced to fairly modest claims about the picture’s formal achievements. I understand why he wants to do this: modesty, human scale, is precisely what he promotes against gigantism and histrionics. It’s what he wants Guernica to preserve. The book ends not with a bang but with a measured encomium to the picture’s sheer unlikeliness:

That I can even claim [Picasso] rose to the challenge – that he found a way finally in Guernica, right at the end, to make his humans and animals come near us and place them on the ground; and a ground that was neither outside nor in, exactly, but the floor of a world as it might be the very instant “world” was destroyed; and where women and beasts, in spite of everything, still fought to stay upright and see what was happening… That I can claim this at all (this enormity), and hope to persuade you, is more than enough.[18]

“More than enough” might be pushing it. Clark’s writing has often made someone else’s failure into its own success. Maybe it’s consistent, then, that when describing a success his prose courts failure. And that, too, may be a rhetorical effect.

…

Picasso, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, 1907

For many of Picasso’s admirers (current population unknown), it will be hard to swallow the claim that the “century’s most difficult pictorial thought” was also essentially conservative. How could Clark seriously argue this of the Demoiselles d’Avignon, for instance? As it happens, he doesn’t try: the painting hardly figures in either this book or the Cubism chapter in Farewell to an Idea. The picture is nothing if not some Nietzschean riot of room-space gone screwy with sex and terror. (Leo Steinberg is good on this).[19] There is very little that strikes me as conservative about it; little, indeed, of the nineteenth century. And it would be nearly impossible to discuss the work without considering race and gender in a much more systematic way than Picasso and Truth ever does. The Demoiselles scrambles Clark’s coordinates before they’re even supposed to be established. 1907 is before Cubism proper, after all. Thus its near-absence feels symptomatic. Object choice strikes back.

Picasso and Truth has other concerns besides room-space, though. For one thing, Clark makes short work of biographical interpretations of Picasso’s art (girlfriend x = painting y is the general formula), and his reasoning is sound enough: “Picasso is a painter who says ‘I.’ But I is someone else.” Certainly. A second charge against the version of Picasso that Clark wants to defend, the Picasso of the 20s and 30s, is more profound and accordingly leads to more extreme countermeasures. I have already touched on this matter repeatedly. Time to face it down.

…

Is it not the case that the decades of minotaurs and maidens are a huge regression from the achievements of Cubism, which had achieved some real clarity about the workings of the sign? Isn’t all of this reactionary? Yes, is Clark’s answer, in effect: but there are extenuating circumstances. For one thing, everyone was doing it: “[T]he longer I live with the art of Europe and the United States in the twentieth century (I mean the short twentieth century from 1905 to 1956, from the first Russian Revolution to Hungary and Suez), the more it seems to me that retrogression is its deepest and most persistent note.”[20] Modernism wanted to hold on to anything it could, however fantastic. Better that than cold embrace of the new. The modernisms that are still worth anything to Clark were apotropaic, not anticipatory. Artists were forced to be radicals because they wanted to be conservatives, Clark seems to imply: they were driven to formal invention in order to preserve what they could of the old bourgeois order. Historians who want to see progression from one modernist triumph to the next are deceiving themselves about the shape of the century’s art. More seriously, they are deceiving themselves about the shape of the century itself – because it had none.

“I do not see a shape or logic to the last hundred years,” Clark writes:

I see the period as catastrophe in the strict sense: unfolding chaotically from 1914 on, certainly until the 1950s (and if we widen our focus to Mao’s appalling “Proletarian Cultural Revolution” – in essence the last paroxysm of a European fantasy of politics – well on into the 1970s). It is an epoch formed from an unstoppable, unmappable collision of different forces: the imagined communities of nationalism, the pseudoreligions of class and race, the dream of an ultimate subject of History, the new technologies of mass destruction, the death throes of the “white man’s burden,” the dismal realities of inflation and unemployment, the haphazard (but then accelerating) construction of mass parties, mass entertainments, mass gadgets and accessories, standardized everyday life.

Never mind that Clark has in fact nicely mapped the unmappable collision. Is it the case that there is no logic here? There is one, though it’s purely subtractive: Clark, as we have seen, calls it the “end of something called bourgeois society.” Equivalent to the end of the nineteenth century. Nothing takes over from bourgeois society, it seems; the only legacy left is more incoherence, violence, of an updated sort. (“Spectacle” is another name Clark uses for this, though not, so far as I can recall, in the new book – he was a member of the Situationist International for a time in the 1960s and sometimes the old language reappears).

It’s a perspective that follows – or maybe it precedes; the question of priority is not really important – from Clark’s renunciation of Marxism. His statement on the matter in Picasso and Truth has the clarity of a penitent’s catechism:

Marxism, it now seems, was most productively a theory – a set of descriptions – of bourgeois society and the way it would come to grief. It had many other aspects and ambitions, but this is the one that ends up least vitiated by chiliasm or scientism, the diseases of the cultural formation Marxism came out of. At its best (in Marx himself, in Lukács during the 1920s, in Gramsci, in Benjamin and Adorno, in Brecht, in Bakhtin, in Attila József, in the Sartre of “La conscience de classe chez Flaubert”), Marxism went deeper into the texture of bourgeois beliefs and practices than any other description save the novel. But about bourgeois society’s ending it was notoriously wrong. It believed that the great positivity of the nineteenth-century order would end in revolution: meaning a final acceleration (but also disintegration) of capitalism’s productive powers, the recalibration of economics and politics, and breakthrough to an achieved modernity. This was not to be. Certainly bourgeois society – the cultural world that Picasso, Matisse, and Malevich took for granted – fell into dissolution. But it was destroyed, so it transpired, not by a fusion and fission of the long-assembled potentials of capitalist industry and the emergence of a transfigured class community, but by the vilest imaginable parody of both. Socialism became National Socialism; Communism, Stalinism; modernity morphed into crisis and crash; new religions of volk and gemeinschaft took advantage of the technics of mass destruction. Franco, Dzerzhinsky, Earl Haig, Eichmann, Von Braun, Mussolini, Teller and Oppenheimer, Jiang Qing, Kissinger, Pinochet, Pol Pot, Ayman al-Zawahiri.

This is a highly characteristic specimen of recent Clarkism, not least for the torrent of names let loose at the end, as if their mere invocation sufficed. Why, though, is Clark’s judgment on Marxism (and on the century during which it gained traction) so different now, when all of those names and their significance, with the exception of al-Zawahiri, would already have been known to him when he was writing his books of the 1970s and 80s? Why does this look so much like a vast swath of the last century’s reactionary discourse?

An archaeological dig is in order. Things were not always thus for Clark. At various points earlier in his career, Clark insisted not only on the missed encounter between art and bourgeois society’s determinate rather than merely chaotic negation, but seemed to suggest its continuing feasibility. In other words he affirmed the feasibility of proletarian revolution. With this, modernist art could potentially have had some truck, and thus remedied its terminal hemorrhaging of significance. Take for instance an essay I have already cited, “Clement Greenberg’s Theory of Art,” published in Critical Inquiry in 1982. Clark here takes issue with the great American critic’s shriveled account of modernist negation. In the process he also reconstructs Greenberg’s own early Marxism. This is from Clark’s last paragraph:

There is a way – and this again is something which happens within modernism or at its limits – in which that empty negation is in turn negated. […] [T]here is an art – a modernist art – which has challenged the notion that art only stands to suffer from the fact that now all meanings are disputable. There is an art – Brecht’s is only the most doctrinaire example – which says that we live not simply in a period of cultural decline, when meanings have become muddy and stale, but rather in a period when one set of meanings – those of the cultivated classes – is fitfully contested by those who stand to gain from their collapse. There is a difference, in other words, between Alexandrianism and class struggle. The twentieth century has elements of both situations about it, and that is why Greenberg’s description, based on the Alexandrian analogy, applies as well as it does. But the end of the bourgeoisie is not, or will not be, like the end of Ptolemy’s patriciate. It will involve, and has involved, the kinds of inward turning that Greenberg has described so compellingly. But it will also involve – and has involved, as part of the practice of modernism – a search for another place in the social order.

I suspect this already would have sounded old-fashioned to some of Critical Inquiry’s readers in 1982. At any rate, there is a notable shift of emphasis between this essay, as well as Clark’s first go at an interpretation of Olympia,[21] on the one hand, and his revised treatment of the same material in The Painting of Modern Life. The earlier essays insist on the possible availability of counter-representations, “meanings rooted in actual forms of life; repressed meanings, the meanings of the dominated” (this is from the piece on Manet in Screen), rising from elsewhere in society: he means rising from the proletariat. These could have been the material of a different modernism. Absent such regrounding, though, the “free play of the signifier” that some see in Manet only discombobulates the order of representations, while leaving its structure intact. A new order (a set of new meanings) would be necessary to really disrupt the “dance of ideology.” It’s an odd claim, on some level at least: what would Olympia look like if it had truly been painted out of an identification with a female and proletarian subjectivity? Like no modernism we’ve ever seen. And of course we could hardly expect this from Manet, who was a bourgeois male through and through. Thus the demand remains an awkward counterfactual. Out of such stuff are manifestos made, but not art history. Clark here is too willing to show his hand to really be convincing.

The explicitness is gone by 1984. It may be that the whole pathos of Clark’s later writing on modernism originates in the loss of this horizon. What was lost, or rather what in fact never occurred (though as late as 1982 he seems to have thought it might still have been a future possibility), was an avant-garde that could recover its social basis in the experience of a different class, one plausibly on the cusp of totalizing that experience in its achieved hegemony. Revolution, then, as remedy for the world’s disenchantment. All of this was presumably a bit too much optimism à la William Morris even for a younger T.J. Clark, and so it doesn’t ever get expressed quite so baldly as I’ve put it. And at any rate it was a passing phase. All the same I think there is no other way to explain the shift between his early writings and the late. At issue here is perhaps not exactly a realist imperative with its conditions of possibility crossed out – though parts of Picasso and Truth raise that specter – but rather a stubborn determination not to be taken in by the critical substitutes on offer. I have in mind, to name a few: Greenberg’s late doctrine; Michael Fried’s continuation of the same by other means; the October school and their seductive marriage of formalist rigor to a diffusely left politics; postmodernism as a whole... the list goes on. A losing battle, though, since by all accounts a proletarian modernism for the 80s failed to materialize. (That’s harsh, but how else to convey the specific tenor of the essays in Screen and Critical Inquiry?)

Clark states plainly in Farewell to an Idea: “If I cannot have the proletariat as my chosen people any longer, at least capitalism remains my Satan.” It has not yet been sufficiently noted how profoundly this declaration colors the author’s picture of modernism itself: it thereby loses its possible regrounding in representation (“representation” here understood as a social practice that occurs in constant relation to other social practices). Socialism was for a century the dream – Clark also calls it a myth – of just such a totalizing practice. Its death is a fact of art history because with it also died modernism’s possible realization: it was what could have made the “social reality of the sign” something tangible and open to conscious direction. It turns out, of course, that when modernist art approached this threshold it mostly became ghastly. Consider El Lissitzky’s propaganda board in Vitebsk, shouting to passersby in the war year of 1920: The Workbenches of the Depots and Factories are Waiting for You. Let Us Move Production Forward. (Clark’s translation in Farewell.) Picasso at least was never so malleable even in his Communist years. The direct encounter between art and socialism is a limit case within the limit-pushing that is modernism as a whole; it was horrific because socialism was horrific, and socialism was horrific because it was part and parcel of the modernity it half-opposed, half-embodied. In these circumstances conservatism in art doesn’t sound so bad, if it is at least undeceived.

…

I would rather avoid agreeing to this. All the same it strikes me as about as good a way to understand Picasso as any yet ventured. The readings of the pictures are evidence enough. The danger here is that Clark will vitiate Picasso’s (artistic) radicalism, more on account of his conceptual armature than in the specifics of his descriptions, which are often admirably sensitive to the bizarre. We need a weirder Picasso, not a more rueful one. Clark is right, though: Picasso clearly was a conservative of a particular sort; he was in the modernist game for the sake of “Bohemia’s last hurrah,” not the “whirling glimpse into a world-historical present-becoming-future.” And who could blame him? A few last observations are needed, though, if the goal is to salvage Picasso and Truth for a less anguished anti-capitalism.

…

Picasso, Nude Standing by the Sea, 1929

The pessimistic turn in Clark’s writing seems to me bound up with his basic understanding of what modernity is. To avoid the reformist or arguably reactionary conclusions in his recent statements on politics (in addition to Picasso and Truth I especially have in mind his 2012 essay, “For a Left with No Future”),[22] it will not be necessary to affirm any greater optimism of the will, but rather to change the terms of the debate. I will bracket Picasso and Truth because it seems to me no longer to offer an all-embracing concept of recent history except as tragedy, catastrophe, and this does not invite critique – only assent or futile protestation.[23] In Farewell to an Idea, though, Clark makes a few attempts at a definition of modernity. It’s notable that his language is mostly not Marxist but Weberian. Here is a patchwork of quotes from the book’s introduction:

“Modernity” means contingency. It points to a social order which has turned from the worship of ancestors and past authorities to the pursuit of a projected future – of goods, pleasures, freedoms, forms of control over nature, or infinities of information. This process goes along with a great emptying and sanitizing of the imagination. Without ancestor-worship, meaning is in short supply – “meaning” here meaning agreed-on and instituted forms of value and understanding, implicit orders, stories and images in which a culture crystallizes its sense of the struggle with the realm of necessity and the reality of pain and death. The phrase Max Weber borrowed from Schiller, “the disenchantment of the world,” still seems to me to sum up this side of modernity best. […] “Secularization” is a nice technical term for this blankness. It means specialization and abstraction; social life driven by a calculus of large-scale statistical chances, with everyone accepting (or resenting) a high level of risk […]. I should say straightaway that this cluster of features seems to me tied to, and propelled by, one central process: the accumulation of capital, and the spread of capitalist markets into more and more of the world and the texture of human dealings. […] And the true terror of this new order has to do with its being ruled – and obscurely felt to be ruled – by sheer concatenation of profit and loss, bids and bargains: that is, by a system without any focusing purpose to it, or any compelling image or ritualization of that purpose.

To sum up: modernity is privative. It builds incdredible things but they do not belong to the people who live in and amongst them. It drains the world of meaning and offers nothing but calculation in its place. This threatens to align Clark with a critique of modernity from the right rather than the left: and indeed Eliot and Pound, to take the strongest examples, are omnipresent touchstones for him. Modernism, if understood as issuing from this state of affairs, must reflect, resist, or attempt to compensate for such loss. Sometimes it aims to accelerate modernization in the mostly deluded hope of thereby gaining control over it. Its struggle will almost necessarily be a losing one.

What if, however, we shift the weight of Clark’s emphasis away from “disenchantment” towards the “accumulation of capital” – what if the latter were to be put center-stage, taken as central from start to finish in our analysis, rather than reduced to a parenthetical aside? What if we were to describe capitalism itself not as the spread of certain habits of mind or patterns of relation (means-end rationality; speculation and hedging against contingency; decay of traditional authority), nor yet as a chain of unfathomable catastrophes, but rather as the determination of a social totality by its progressively thoroughgoing subordination to a specific social form, namely, to the relation crystallized in the value-form of the commodity? Modernity would then no longer appear as an unaccountable calamity (though in its experienced effects it does surely remain this) but rather as that shape of society produced by the dominance of the most basic mediation specific to capitalism and capitalism alone: the making-comparable of all commodities by means of their expression in something called exchange value, and the extension of this relation to practically the entire globe. No teleology needed: only the fairly obvious point that the decay of “bourgeois society” – in the narrow sense of the term, that is, more or less as a synonym for the European nineteenth century – did not leave nothing behind, but rather a different social totality with its own characteristics, its own mode of reproduction. (Otherwise the death of nineteenth-century bourgeois culture would have been a literal apocalypse: human extinction.) Such a world is not resistant to theorization a priori. To conceive Marxism as concerned with the description of such mediations, such abstractions, as constitute the changing phenomenal form of the class-relation (the antagonism as well as the fundamentally linked reproduction of labor and capital, and the development of this relation over time), is very different from conceiving it as essentially “a theory – a set of descriptions – of bourgeois society and the way it would come to grief.” Though this may be, for Clark, what Marxism was “most productively,” it is not what Marxism has to be now. Clark’s definition is parlous; I prefer another, but not abandonment of the bitter acknowledgments that Clark’s work has made possible.[24]

…

In this I am exactly opposed to what was long majority art historical opinion: I think Clark’s project is not determinist, not Marxist enough. And it gets worse the farther he retreats from Marxism and determinacy. But in saying so I am not insisting on doctrinaire application of a set of Marxist clichés (paging Comrade Zhdanov). I am insisting on the potential of Marxist theory, and Marxist art history, to be more than a period style. Anyone making such a claim should be careful to say what is not meant, because philistinism looms here. I have read one review of Picasso and Truth in which the author held up Picasso’s entry into the French Communist Party – in 1944 – as a rebuke to Clark’s “retreat into an art for art’s sake.” It would hardly be worth noting this absurdity if it did not index in a pungent way a certain leftist ignorance of history that is one side of the double-bind to which Clark’s book has fallen victim. The other side is the ignorance of (some) art historians. For the latter, Clark’s work (essentially his prose style) has always been excessive, a crime against decorum. All that doom and gloom, all that fussing about the world-historical significance of this or that patch of paint: isn’t it a bit much? What’s wrong with good old-fashioned semiotics, anyway? And on the other side: Picasso was a communist, full stop. Speak no ill of the dead. The repressed term in either discourse might as well be Stalin. I am asking for a criticism that is smart enough to know who Stalin was and still want to destroy capitalism anyway.

T.J. Clark, Picasso and Truth: From Cubism to Guernica, Princeton University Press, 2013

[1] Jacques-Louis David’s Marat suggests as much.

[2] I have only the faintest idea what those names signify, but whatever: synecdoche is a primary mode of Clarkian rhetoric.

[3] London Review of Books, November 17, 2011. I note with interest that this essay is dated to the Thursday I was marching with tens of thousands of others in support of Occupy Wall Street following its violent eviction from Zuccotti Park two days before. Call it synchronicity.

[4] The object of one of Clark’s most important interpretations, in The Painting of Modern Life: Paris in the Art of Manet and His Followers (Princeton University Press, 1984).

[5] Critical Inquiry 9, no. 1 (Sept. 1982), pp. 139-156.

[6] It’s significant that The Sight of Death stands in uncertain relation to Afflicted Powers: Capital and Spectacle in a New Age of War, by the Bay Area-based collective Retort (Verso, 2005). This was Clark’s other major writing project of the mid-2000s.

[7] Picasso and Truth itself was first delivered as a series of lectures in the spring of 2009, that is to say in the depths of the Great Recession. I happened to witness a version of these lectures at UC Berkeley that November, only a few days off from the occupation of Wheeler Hall by students resisting a 32% tuition hike. Synchronicity again.

[8] This echoes a sentence in the introduction to Farewell to an Idea: “There could have been (there ought to have been) an imagining otherwise which had more of the stuff of the world to it.” Clark says this in the context of an argument about modernist art’s complex relation to socialism: “Socialism occupied the real ground on which modernity could be described and opposed; but its occupation was already seen at the time (on the whole, rightly) to be compromised – complicit with what it claimed to hate. […] I am saying that modernism’s weightlessness and extremism had causes, and that among the main ones was revulsion from the working-class movement’s moderacy, from the way it perfected a rhetoric of extremism that grew the more fire-breathing and standardized the deeper the movement bogged down on the parliamentary road.”

[9] For semiological interpretations, see: Krauss, “In the Name of Picasso,” in The Originality of the Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myths (The MIT Press, 1985); Bois, “Kahnweiler's Lesson,” in Painting as Model (The MIT Press, 1990); Bois, “The Semiology of Cubism,” in Lynn Zelavansky, ed., Picasso and Braque, a Symposium (Museum of Modern Art, 1992), as well as Krauss, “The Motivation of the Sign,” in the same volume. Krauss returns to these issues, with an eye to the artist’s post-1914 work, in The Picasso Papers (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1998).

[10] Clark says that “Collage was happy with deception.” Which is a problem. Clark wants his Nietzscheanism conflicted.

[11] I see no reason why a different selection of pictures might not have yielded an entirely different and equally defensible set of themes. There is a tendentiousness to Clark’s habit of making whatever aspect of the matter at hand that chances to align with his own concerns simply be what that thing is really about. This is true also of his recourse to theory. Adrian Rifkin coined the memorable phrase “Marx’s Clarkism,” in his review of The Painting of Modern Life (“Marx’s Clarkism,” Art History, vol. 8, no. 4, [Dec. 1985]). My own examples of similarly strong (and problematic) appropriations would also include Clark’s use of Paul de Man, in Farewell to an Idea and elsewhere – see his “Phenomenality and Materiality in Cézanne,” in Tom Cohen, ed., Material Events: Paul de Man and the Afterlife of Theory (University of Minnesota Press, 2001) – as well as, most recently, his mobilization of Nietzsche. For an entirely different attempt to bring Nietzsche to bear on Picasso’s post-Cubist work, see Sebastian Zeidler, “Life and Death from Babylon to Picasso: Carl Einstein’s Ontology of Art at the Time of Documents,” in the seventh issue of the online journal Papers of Surrealism (2007), and more recently his book Form as Revolt: Carl Einstein and the Ground of Modern Art (Cornell University Press, 2015).

[12] Pictures frequently speak in Picasso and Truth, to us or to each other. They are often “saying” something. Clark is a medium through which their propositions announce themselves. This is a strangely animist mode of criticism and I know some art historians who are not happy with its self-assurance.

[13] I’m not sure why “mimesis” wouldn’t be as good a word as “truth.” It would open up a very different interpretive horizon.

[14] I mean a socialism-in-pictures, if such a thing makes sense. Picasso’s politics are a contentious topic. As a young man he was close to anarchism. In the interwar period his affiliations were promiscuous; in a recent review of Picasso and Truth, Malcolm Bull has taken advantage of this fact to argue (wrongly, in my opinion) for a link between Picasso and fascism. (“Pure Mediterranean,” London Review of Books Vol. 36, No. 4 [Feb. 20, 2014], pp. 21-23.) Later the artist was a card-carrying Communist, as the saying goes.

[15] This section of the book elaborates thoughts on infantile states and the origins of sexual difference that first appear in the Cézanne chapter of Farewell to an Idea. Clark acknowledges his debt to Jeremy Melius’s brilliant reading of the Tehran picture, since published as “Inscription and Castration in Picasso’s The Painter and His Model, 1927” (October 151, Winter 2015, 43-61).

[16] For another account of Guernica that poses some of the same questions, see Daniel Marcus, “Guernica: Arrest and Emergency,” in Yve-Alain Bois, ed., Picasso Harlequin (Skira, 2009).

[17] What to call this method? Social history of art it isn’t, not in any way we’ve come to know it. I find myself groping for hybrid terms: formalist humanism? a political phenomenology of pictures? Clark no longer provides methodological introductions.

[18] Ellipsis in the original.

[19] “The Philosophical Brothel,” October 44 (Spring, 1988), pp. 7-74. (Originally published in 1972.)

[20] Needless to say an immense number of modernist practices would appear to directly contradict this statement. Futurism, Dada, the whole of the Soviet avant-garde… Of these Clark has only written at length on the last, in a chapter on Lissitzky and Malevich in Farewell to an Idea, so how exactly he reconciles a claim like the one I’ve cited with the historical record is not easy to judge.

[21] “Preliminaries to a Possible Treatment of ‘Olympia’ in 1865,” Screen vol. 21, no. 1 (1980), pp. 18-42.

[22] New Left Review 74 (March-April 2012).

[23] Though for a critique of “No Future,” see Alberto Toscano, “Politics in a Tragic Key,” Radical Philosophy 180 (July/Aug. 2013), pp. 25-34; also, Susan Watkins, “Presentism?” (a point-by-point response to Clark published in the same issue of the NLR).

[24] In Picasso and Truth, Clark dismisses in three parenthetical sentences the rubric of “commodification” as a possible master-narrative for the history of the twentieth-century’s art. I can sympathize if what he means to catch by this is some constellation between, say, October, Texte zur Kunst, maybe e-flux, too: the soft-leftist art world common sense that migrates easily between academic journals and gallery press releases. It’s a wide net for him to cast, however, and I am not sure that what I am describing – the imperative to periodize modernity in terms of the development of the class relation, for example from the growth of a consolidated proletariat during the heyday of the workers’ movement to its decomposition after World War II – is thus damaged at all. I am not talking about “commodification” as some undifferentiated process that befalls one thing after another and always in the same way; I am interested, rather, in how a whole complex of relations, one of the most important being the commodity-form, come to subsume and determine various aspects of a social world, not piecemeal but with effects that ripple throughout the whole of its structure (including the realm of the aesthetic). This has the virtue or vice, depending on how you see it, of ditching the pathos of losing habitable worlds – a crypto-Heideggerian theme, I feel – and instead focuses on how any given world is made, how it is produced and reproduced. Such worlds are not made as the negation of some supposed former stability (the bourgeois civilization of the nineteenth century), but in the continual, constant processes of their (re)constitution, which essentially takes place by the ever-repeated positing of certain determinate social forms – the wage or the family, for example.

To understand how this happens, we need definitions as precise as possible of things like “value” or “the commodity.” Definitions that are not an ersatz theology but dynamic tools with which to understand, and to attack, a world of constant change. Hence the mode of production remains, for me, the horizon of any hermeneutic. This is also another way to reconsider the feminist critiques that were put to Clark’s work in 1980s and 90s: by occluding reproduction, Clark occludes much of what women do in capitalism; they become flat signifiers for men like Manet to bandy around the superstructure. Olympia is the still the key reference here. Marxist feminism doesn’t only make for better politics, it makes for better art history: it allows for accounts of pictures such as Olympia (and probably, we might add, of many of Picasso’s works) that Clark is evidently unwilling to countenance. Lastly, my argument is not that a fixation on the value-form or any other mere category will explain everything about the period in question – it can’t directly explain something as unimaginable as the Holocaust – but rather that these concepts give us a better way to understand what modernist art was about than does an emphasis on the consequences of disenchantment.

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com