Listener as Operator (2)

What happens when musicians smash the metronome of developmental time and the prison-house of language?, asks Howard Slater in this month's Mute Music Column

On the way to a full silence the mark of language

brands the body with a reminder of the time

- Delphine

Tellingly Inarticulate (2)

At a recent performance at ‘Freedom of the City 2010', trumpet player Wadada Leo Smith reversed virtuosity for a moment. Virtuosity being no virtue, time stood still a little, time that normally in these moments races ahead with a neurotic fidgetiness, here almost descended into a silence that could have prompted vague paranoias. Is it finished? Has it kiltered? Can I hold this abeyance, this break to the flow that is my desire to be led? What could this respite be a prelude to? From the silence came a sputtering tubular saliva phisp. This sound was no perfectly sounded slaver of a too-smooth dirty timbre befitting the studiousness of a chamber quartet. The latter are tellingly articulate and they tell of a time that must be filled with meaning, a time in which silence would be a disastrous trapdoor that devolves the institution of the performance. Silence here would be like a strike, a go-slow, a cheating of the audience, a plateau phase. For Wadada Smith, and maybe his lineage assists us to relax in this, there seemed to be an aimed-for silence from which the muttering of his trumpet began again to speak articulately. Here, in this brief moment of brass smears, the struggle for the means of expression, an ever rejuvenating staple of jazz, was staged again. A building up from the wavering foundation; a hiatus in time to alter the density of the space.

Writing, in 1973, of his approach to improvisation, Wadada spoke of there being ‘no intent towards time as a period of development. Rather time is deployed as an element of space...' Where does development end? In a kind of untouchableness? A kind of constantly arrived-at elevation that suppresses the struggle of beginnings? In some ways such telling inarticulacy as Wadada's (this time) can extend the ‘affinity dynamic' out to the listener and away from the stage in a kind of ‘lateral depth'. The ‘element of space' that is deployed in the ‘breakdown' is, as ever, a kind of ‘interior' space that raises the question of our ‘being-with' not only the performers, but our fellow audience members. Beyond a virtuosity of development there could be, with a telling inarticulacy that wills its own vulnerability, the offer of a social relationship: a development of our relationality not only in the moment, but as that which begins again in a musically induced reposing of an affecting exposure to bare life; a laying bare prior to a constitutive moment.

Out Of Time

Maybe Wadada's statement rings out like a blat for other improvisers. You can, when hearing the constantly undulating solos of Eric Dolphy on such tracks as ‘Iron Man', be in the presence of an arrow that's flying directly to somewhere we know not but which we do know doesn't arrive at a target. It sets off from some place that could be notated but notes in potentia seem to split up into atoms that forms a cloud around the ‘line' as it moves. The choice in the milliseconds is which of the note-atoms to hop to whilst seemingly playing ‘as the crow flies'. So, again, ‘direction' or ‘directionless' seem hardly the right ways to speak of such solos as these and say those of John Coltrane on ‘Stellar Regions'. Instrumental proficiency in these and many other cases seems to be about sounding instinct, bringing impulse to bear against time in an intoxicating suspension that, in outflanking language, somehow seems to suspend time.

For someone such as Dolphy, who jammed with the birds and fluted with the waves, it was hardly timeliness he was after. As the authors of his musical biography have attested, moments on his still much acclaimed Out to Lunch LP have a ‘double time feel' and Dolphy himself spoke about incorporating ‘free time' in his, well, compositions; a desire that extended, he informs us, to replacing the piano (that ‘seems to control you') with the more open and spacious sound of Bobby Hutcherson's vaporous vibes. Is it possible then that the continuing appeal and who knows, resurgence, of interest in ‘free jazz' may well be informed by a desire to escape or seek respite from the heavily demarcated chronos of the abstract time of capital; the sucking up of time that seeks to forever defer ‘disposable time'? For, as opposed to the three minute pop song that seems to be the perfect cultural form for the music industry, (i.e. constantly consecutive and conducive to the production of quantity), our sense of time when we listen to, say, a free jazz ensemble piece is one that is not over before it's begun. Such abstract time, a time of instant gratification, doesn't give us a ‘now' that is long enough to open and establish a relationship to time in. Not only this but there is, as part of the time-slip of free jazz, a sense of simultaneity (‘duet unison') whereby the present moment of listening becomes a condensed deceleration of duration that doesn't run towards developmental meaning but makes time thick. Dolphy: ‘The bass follows no bar line at all. Notice Tony. He doesn't play time, he plays'.

Image: Eric Dolphy and John Coltrane.

‘Intempestive Atopians'

Temporal dynamism, then, somehow needs the presence of more than one and when, either bereft of a ‘being-with' or in an attempted effort to devote ‘living attention', it is the ensemble sound that most easily allows us access to our component selves, to the society of our intra-psychic groupishness. An interior population, then, could be an indication that we are present to ourselves at the same time that we are present to the multiple pasts of ourselves. It is an indication that our emplacement is always intertwining with a displacement. Coming up for air after listening to such a tempestuous track as the ‘Utter Nots' by Sun Ra and his Solar-Myth Arkestra, it is as if we need a time of readjustment to avoid the psychical benz that has made us ‘intempestive atopians' (not only do some of Ra's piano lines sound out of place, other-roomly, there is, after a steady unison pulse at the beginning, a kind of percussive flailing that doesn't so much mark time as attempt to break its partitioning effects). All the component parts of our self, parts that contain the precipitates of relationships, seem to have been provoked into ‘parallel lives' by the component parts of the ensemble and the concentrated fury of the soloists as they each take it to the brink of inarticulacy. The bundle of affect we brought to the listening was not assuaged by a ‘naming ceremony', there wasn't feeling as such, neither was there specific emotion. Most definitely there was not some self-centric unity, some boundaried possession of our social experience made possible by a single track, but an ‘utter not' of dispersion, a diffusion of an abated self in ‘non-controlled time'(the date of the session can't be pinpointed and the track feels much briefer than its stated eleven minutes). The ‘intempestive', then, should maybe not be taken as a transcendence, nor be mistaken for nostalgia. Sun Ra, with his ease of musical access to different times and his sustaining investment in different places, has perhaps made it more clear to me that this supposed cacophony is meant as a complete refusal of both time and place as they are now structured (an utter not to it). It is as if some form of communism has been audibly experienced; a communism that gives us a glimpse of some kind of ‘ontological thickness' that encourages both an ‘amended reissue of the past' and a lack of debilitating fear before the trauma of the ‘narcissistic wound'. Proust: ‘... my actual life... appeared to be comprised in a larger reality which had not been created for my benefit.'

Music and Agony (2)

Feelings of disassociation from time and place accompany the wound of the bereaved who can no longer rely upon the presence of a loved one, no longer rely on that narcissism, that reflected love, that, in other circumstances may well have been the submerged sop of dependency, may well have provided the modicum of temporary unity for a centripetal self-image. The ego, its ideal, may well have need of a gradual disassembly, the prop of which, the being-with as the prop, has now been removed. The affective stakes are raised in a such way that ideological sublimation and rational appraisal prove insufficient to meet the demands of amorous mourning. A certain conserved idyll meets the absence of its ongoing propellant. Are those who bear this affective state drawn to music so as to be nearer to their fellow ‘intempestive atopians'? Can their music ease the ache of a hole rather than fill it? As they said of Dolphy, there is a ‘direct emotionalism' at play. There seems to be less between us because there is less language there to take the place of the affect, less language to draw us towards misunderstanding. It's almost as if sincerity and language could be in inverse ratio.

This space of listening, as a potential space that is neither too close in its offer of sympathy, nor distanced enough to be a cold unaccompanying, is, as Winnicott has put it, a space of ‘relaxed undirected mental inconsequence'. So, in their active passivity, are the bereaved drawn to music for its qualities of a lightly guided daydreaming, for its offer of a ‘free floating attention' that could just as well drift into a temporary forgetting? Again the ‘indirection' of many of Dolphy's solos, which nonetheless sound out with a velocity, a passage, are such that there can be a passing-through, a momentary overcoming of acute discomfort that at least provides a cessation to an, albeit natural, intense self-focus, replacing it with the revivifying call of another. There is a drawing out. There is a being taken to the horizon to get a better view. There is more and more of an offer of less and less mediation.

‘We Dare to Sing'

There are times during ‘Offering' by John Coltrane where the mediation of the instrument, its being a prop, is replaced by a sense of directly hearing a kind of ‘semiotic of the impulses'. Here, an embracing of spontaneity, with its limiting of an over-preparation, allows for an access to affect and a propulsive, non-abstract time that allows for these affects to unfurl at their ‘own speed'. As Coltrane enters a solo phase he repeats a motif in a tight and circular form, the solo seems stuck, but as it swiftly returns and returns it grows in breadth, it adds tangents of ‘off-time', of inarticulate sax-cracks. It becomes like a catherine wheel that spins back to the start but gives off random and fortuitous sparks that speak of a temptation to break the tightness of the repetition by harnessing the friction of competing affects.

On the track ‘We Dare to Sing', another tenor saxophonist, John Tchicai, in duet with drummer Tony Marsh, creates a similar effect of suspension. He begins this piece with a kind of wordless wailing that falls somewhere between singing and mourning, celebration and self-effacement. The track confidently stages inarticulacy by beginning from this kind of zero ‘craftless' position of vocalising. Before Tchicai blows a note on the saxophone we hear the ‘bare life' of breath that summons up the temporal dynamism of the intempestive: singing as ritual, as catharsis, as joy, as a distribution of vulnerability. Tchicai dares to sing, dares to offer something less than polished, but he also stages a kind of founding contrast between the unmediated breath of wailing and chanting and a channelled breath that figures his tenor as a recent machine. The suspense of this track, then, is announced from the outset: what follows the voice? Is it words and language or something prior to these? Is there something in a language made impermanent that can be rejuvenated by the unmooring sounds of affect?

Diabolical Vocason

The power of those that use the human voice as their instrument may lie in the risks entailed in doing an uncivilized violence to the founding rigidities of language. There is something agonising and off-putting in hearing what sounds like the most unmediated of musical practices through which music, its hopes for coherence and meaningfulness, are sorely profiled. Such vocalising may not so much be tending towards language as withdrawing from it, retracting from a social contract. At times, listening to Demetrio Stratos or Phil Minton can have the simultaneous effect of being close to someone in pain, close to a primeval event and close to the communicative sounds of a rejuvenated species. We're in a forest, a tunnel, an ancient plain... the dictionary is burning. Stutterers know this splintered harmony and interrupted flow and they are aware too of the alienating facial contortions that become necessary for speech to ‘come out' as a cough, as a deep inhalation of bubbled breath. There are sonorities here, there are what sounds like fragments of words, vowels and consonants ringing out from an unfamiliar place in the vocal tract, there are technical tricks (annotated ad infinitum in Trevor Wishart's book On Sonic Art). But there is also the wonder of a ‘telling inarticulacy' that sounds-out with a visceral presence unmediated by the desire for a speech-led individual continuity (the hall of mirrors set up by the approximations of language).

Are such performances as these discomforting in that they are akin to a regression, to a staging of the dialectical interrelation between infancy and adulthood? Is it that they challenge us to a non-conditional ‘living attention' in which in-bred judgment is suspended? Are they refusals to bring the dispositifs of language to bear once again and have ourselves be the object of the already communicated? Do these ‘geckering screeches' disturb us in their bringing into a public space the warded-off sounds of the pre-articulate; the sound of suffering (phôné) that is well and truly exiled from political representation? Stratos, inspired by his daughter's babbling, offered as his motivation that ‘the richness of the vocal sound gets lost in the acquisition of language'. Could this mean that such vocalising can awaken us to a bodily capacity that has been lost, the repressed sounds that we carry within us which remain unexpressed since there are very few situations permissive enough? Are wordless affects summoned in this way? Can this, in turn, mean that there is always something that outstrips us: a potential in redirecting breath, an immanence of infancy? Is ‘lip flabber' more liberating than discourse? Luce Irigaray: ‘saying ourselves can't happen without transgressing the already learned forms.'

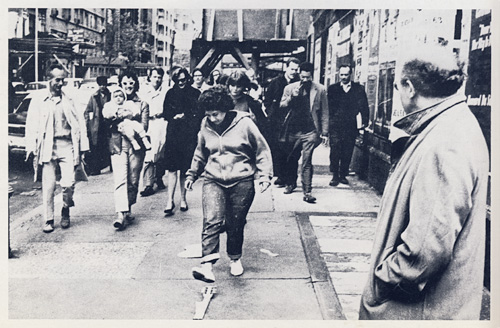

Image: Kicking Robin Page's Guitar Around the Block, Yam Festival, New York City, May 1965

‘Non' & ‘Un'

A new wave of post-reductionist improvisers seem to be experimenting with this combination of ‘telling inarticulacy' and minimum mediation. At times it appears to have an autotraumatic import. It wants to run the ‘risk of ridicule', it wants to ‘leap from a great height' to ‘subject ourselves and the audience to an obscurely unsettling test'. This move from taking the audience as an object to affront becomes a self-affronting abjectness of unworthy ‘performers' before the ‘total' subject and multiple criticalities of the audience. The offer of participation, or immersive engagement of the audience, is, somehow sidled away by the creation of a ‘dense atmosphere' or ‘lateral depth' that makes any perfectly formed discourse object of critique seem weighty with its own self-mediating bid for power. If an immanence is created in the stead of the known knowledge of expectation, it is a kind of ‘unthought known' that can fill the reductionist silence, not with the delayed intention of the musicians, but with a distributed vulnerability and palpable tension. What does such music sound like? In Paris on 1/12/2009 it was the sound of two people sobbing. In a studio in Berlin it was a sound of blastering noise followed by a whimpering that reduced a Wire journalist to hateful invective. On 29/2/2010 in Dundee it was described as ‘creepy' or, later, as being like a group therapy session. On 2/8/2008 in Niort it contained the ‘disintegration products' of several psyches and a passage of crawled, close-up mutterings pierced by phylogenetic screams of refusal. In a booklet accompanying the latter it is possible to read ‘telling inarticulacy' in a description of an intentional process of ‘uncrafting': ‘The practice of uncrafting does not just imply the negation of technique, but the unleashing of a generic potency proper to incapacity'. With no plan (‘we did not know what we might do') and often with no props (four microphones/an unfamiliar instrument, etc.) the self exposure of these performers is akin to a ‘deterritorialising turbulence' in which the child screaming quietly ‘the emperor has no clothes on' is not in the audience but in the performative space. In this moment if no sound is communicated then what could well be communicated is the shared incapacity (how we've been spectacularly incapacitated): ‘I can only be what these inarticulate words make of me: a broken subject, un-unique and spurning the edited time to pretend; a spoken subject: exposed, banal, bereft and plummeting before acculturated expectation'. Music  poetency?

poetency?

Howard Slater <howard.slater AT googlemail.com> is a volunteer play therapist and sometime writer living in East London

Ensemble Players

Ray Brassier, Jean Luc Guionnet, Seijiro Murayama & Mattin, Idioms & Idiots, w.m.o/r, 2010.

John Coltrane, Stellar Regions, Impulse, 1994.

Deflag Haemorrhage/Haien Kontra, Humiliated, Tochnit Aleph, 2009.

Eric Dolphy, Iron Man, Giants of Jazz, 1969/2002.

Eric Dolphy, Out to Lunch, Blue Note, 1964/1987.

Luce Irigaray, The Way Of Love, Continuum, 2004.

Mattin & Taku Unami, Distributing Vulnerability to the Affective Classes, Rumpsti Pumpsti, 2010.

Phil Minton & Roger Turner, Drainage, Emanem 2008.

Marcel Proust, Swann's Way - Part One, Chatto & Windus, 1981.

Jacques Rancière: ‘Communism: From Actuality to Inactuality' in Dissensus, Continuum, 2010.

Vladimir Simosko & Barry Temperman, Eric Dolphy - a Musical Biography and Discography, Da Capo Press, 1971/1996.

Wadada Leo Smith, Notes (8 pieces), excerpted at http://music.calarts.edu/~wls/pages/philos.html

Demetrio Stratos: Metrodora, Cramps, 1976/1989.

Sun Ra & His Myth Science Arkestra, The Solar Myth Approach, Vol.1 & 2, BYG/Actuel, 1971.

John Tchicai/Tony Marsh: ‘We Dare to Sing' on Duets, Treader, 2005.

D.W.Winnicott, Playing & Reality, Routledge 1989.

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com