Slave to the Rhythm: or, the Promissory Form of Labour

Some notes on the new form of wage-labour. Read to the rhythm:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mNAG-oj4PWk

‘…it is the whisper of unremitting demand’

VO introduction to 1987 video for 'Slave to the Rhythm'

I

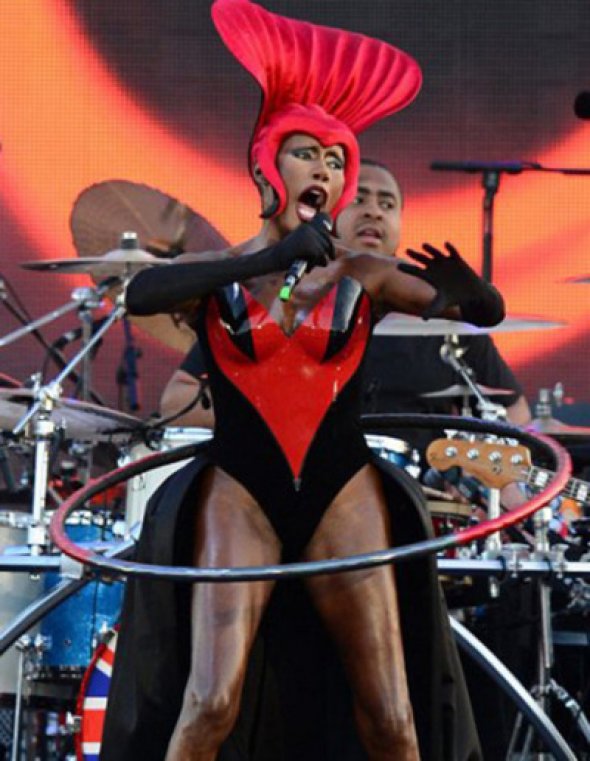

Grace Jones’s performance of Slave to the Rhythm at the Queen’s diamond jubilee crowned a couple of days ‘off work’ in which, for some at least, the working week continued but the labour had become more completely ‘free’ than usual. Free as in unpaid and apparently unlimited. If Jones’s performance was the highlight of a rain-drenched masque, the spectacle was supported by some nigh Elizabethan forms of wage compression. Notoriously, a considerable number of jubilee stewards in the employ of security firm Close Protection UK, slept rough under London bridge prior to their long day of unpaid work, http://www.guardian.co.uk/uk/2012/jun/12/jubilee-security-investigated-unpaid-stewards?newsfeed=true). John Prescott is accumulating the political capital on their investment now, but it seems unlikely they will ever be remunerated for it. This wasn't slavery as such, but rather the essence of the un-waged slave's condition at the cutting edge of UK workfare. And this isn’t a marginal situation or one whose effects are confined to those directly affected – contra to the complacency of Spiked online. As the current crisis deepens, tendentially everyone is becoming an investor in their own future, in the prospect of employment and payment at some, perpetually receding, point. It’s like credit in reverse, the new form of the wage relation. Let’s call it ‘the promissory form’ of wage-labour, generating the promise of valorisation for capitalists whose future is, frankly, no more assured than their victims. The entire system is become a punt on future value that inevitably must fail if any recovery – after however many dips down the dipper – is to arise. This is the secret that the social democratic NGOs and ‘alternatives to austerity’ cabal don’t even know their keeping, and which Krugman, Soros and all their avatars in a now formally anti-austerity capitalist austerity regime dissimulate. This is their role in the wider promissory economy, generating the illusion that were the obstacle of austerity but removed there would be profits, productivity and ultimately jobs and even services for all. Like the classical Lacanian obstruction between the lover and his supposedly so-bountiful object of desire, or the potential abundance to be maintained from a rationally managed capitalism hallucinated by the Stalinist, syndicalist and social democrat reformers, the left-wing of the current devalorisation has to dream a better crisis in order for this one to play itself out to its grim conclusion. The idea that the obstacle can be removed is the thing which constitutes it, that enables the system to continue. Adorno nails the current dynamic: it is always what is possible, never what is real that blocks off the path to utopia.

This is the macro logic, if you like, of the promissory form of value. And this is where such ostensibly frivolous affairs as the jubilee fit in. They give a cultural form to the mass-disavowal exercise even as they immediately embody the form of accumulation they celebrate. They are our contemporary form of Kracaeur’s ‘mass ornament’ – a pseudo-productivist choreography for an economy that is constitutively incapable of producing any more things without gobbling up its own claims on value in a death spiral – a death spiral teams of self-appointed NGO hacks and alternativists all scramble to misinterpret as in some way extraneous to the logic of the crisis, needing just a few little nudges and tweaks to heal. In reality the death spiral is much deeper seated, the foundations of the double dipper more profoundly installed in the bowels of the disaster capitalist theme park in which we live and move and have our promise of future being (terms and conditions apply).

In the promissory form (which might as justly be called the threatening form, the un-free or robust and forceful form), rather than free labour, voluntarily sold and done, the worker is freer – and so more enslaved – than ever. Free not only to sell their labour but to do it unpaid. Not only the classic choice, the double freedom of the ‘dull compulsion of the economic’ whereby one is free to sell one’s labour, and free to die if one does not – but rather the more complete freedom to work and die, to work for nothing. Here we should note that the aesthetic character of the promissory spectacle is already rooted in the very form of work and of (would-be-)accumulation; the form is inherently a performance, a pantomime of value-production, a masque of ‘economic activity’ dependent on labour freely given, labour as a gamble or speculation on the part of the worker as proprietor of her labour-power. In the promissory form it’s as if we were all becoming works of art, absolute commodities with no immediate instrumental purpose, since there is no guarantee that our efforts today will, as promised, lead to further, less unwaged, labour tomorrow.

The view from under the bridge confirms that the jubilee was a crowd-sourced, big-society update of Kracaeur's ‘mass ornament’. For Kracauer, the Busby Berkeleyan spectacle was the continuation of industrial and taylorised labour by other means. Today the form of labour itself is aestheticized by liberation from remuneration. Not just unproductive in ye olde ‘immaterial labour’ sense (an economy of ides, services, pop songs), but non-reproductive (for the worker). Work becomes Mallarmean throw of the dice. An acte gratuit, a gamble, an adventure under a bridge. In the context of the Jubilee the Grace Jones song is reinflected, it’s not about the impersonality of a primal, desiring rhythm, but rather a paen to the involuntariness of this nominally voluntary labour. 'Slave to the Rhythm' loses its psycho-sexual autonomy, its libidinal Keynesianism, and becomes directly a celebration of eternal and compulsive toil. The anthem of in-voluntary labour.

Again, the economic condition is inscribed into the structure of song, of spectacle, of its ‘base and superstructure’ at once. Close Protection UK's un/employees were seeking the possibility of a future paid job on the Olympics gig. A little un/waged slavery today to secure the continuation of their Jobseekers Allowance, with the prospect of proper wage slavery tomorrow. The emergent form of work is so compulsive, so not-dull, that it has the objectively ‘sexy’ (i.e. gratuitous, perversely compelling) character of Jones’ irresistible rhythm. On the one hand one is coerced into unwanted work by the benefits agencies and on the other one is being set free from free labour’s petty concern with the reproduction of the worker. If one takes a punt on future work, it’s a rational calculation, but if one lets go and just takes whatever shit one is handed then one can fully succumb to ‘the rhythm’, to the delicious sensation of doing something for less than nothing. Slave to the rhythm as anticipation of crowdsourcing – give us your ideas in return for our taking them. Slave to the rhythm as collective sacrifice.

Whether speculative or suicidal, the workfare vanguard should be seen as the real stars of the spectacle. Barely perceptible from the stage or the upside of the bridge, and yet not unsung. On the contrary they are directly addressed and commanded: ‘Slave to the rhythm… keep it up, keep it up.’ Grace really is singing to them, even if, in the end, she sends her love to ‘our Queen’. In fact, by addressing her message to the monarch she telematically extends it to all Elizabeth’s subjects, who, in some neo-feudal sense, she represents. The Queen’s two bodies gyrating in time to Grace’s hula-ing one. This makes one realise that the Queen’s infinite abjection – her ability to tolerate anything – is her most sovereign quality. The horror of her existence as life-long sacrifice really does magnify and mirror that of the rest of us, a slave to the imperatives of post-imperial capital if ever there was one. In fact it’s her servility that the jubilee seeks to diffuse and expand: after the celebrations she confessed herself ‘humbled’. How would she feel, one wonders, if subjected to a collective humbling? Liberated? Vogel-frei?

II

Grace Jones is a subject of Queen Elizabeth the second order. The second time Elizabeth. The Elizabeth of the second enclosures, of Caliban & the Witch and Jarman’s Jubilee. That film explicitly pinned the present as a postmodern non-reproduction of the first Elizabethan age. The Last of England is the repetition of the first: looting, credit, misogyny; the subsumption of bodies, lives, populations; cheap labour, capital’s free lunch.

III

Rather than subverting the royals in some way, Jones' work song gave props to the economy in which they functioned as figureheads and lures for foreign direct investment. Their sacrifices to the US-centred client relationship of the post-imperial UK, and ours. The hollowing out of productive industry and the rise of the UK as appendage to the offshore financial services centre of the City of London.

The Queen’s reign was a long journey through deindustrialisation and financialisation to a (post-)post-fordist 'total mobilisation' of the population. The result of this process of restructuring is a society in which all are flexibilised, individuated but socially networked counterparts of Kracaeur's Tiller Girls, throwing value-form imprinted shapes of dubious economic effectiveness. ‘The whisper of unremitting demand’ mentioned in the intro to the 1987 video for Jones’s song, has become worryingly close to inaudible in the present economy. Today total mobilisation means a mummery of futile activity organised by the promissory form of labour – possible future payment and/or employment, backed by guaranteed destruction of value (specifically, the value of the commodity labour-power).

Converging one-way spectacle and the Youmebumbumtrain of contemporary ‘jobseeking’, the jubilee as a whole synthesised cutting edge forms of servitude and an attempt at renewed community. Its glamour was as precarious as its labour pool. Secretly it dreamed of a solution to all these contradictions. ‘Slave to the Rhythm’ looked like some kind of a formula for ideological harmony; the imaginary solution to a very real problem.

‘Work to the rhythm, Live to the rhythm, Love to the rhythm, Slave to the rhythm,’ sang Grace with trademark poker face, hula-hoop spinning ‘round her taut sexagenarian midriff for the duration of the song. The classic sub-dom funk track as eulogy to a world of wage/less slaves who simply LOVE the rhythm of work. Each of us is permahula-ing deathward for the sovereign’s pleasure. This is a rhythm of lifelong labour from which there is no escape, even for OAPs like Grace. ‘Keep it up, keep it up’ – until you drop, pensionless, to the pavement.

It felt like a musical demonstration of Lyotard’s thesis in 'Libidinal Economy' updated for the jubilee: 'The English unemployed did not become workers to survive, they – hang on tight and spit on me – enjoyed the hysterical, masochistic, whatever exhaustion it was of hanging on in the mines, in the factories, in hell….' Keep it up, keep it up!

The 2012 remix of Lyotard’s pre-10-hour-day-movement jouissance is a terrible idea of fun, but it's (not-)working. This is not the ecstasy of extorted industry, productivity, 'growth' etc but a dank and tedious second order toil for no obvious reward. 'Slave to the Rhythm' seemed to say it all, soaking up the background radiation of the Queen, of Close Protection UK and their contractually un-free labourers. Jones couldn’t but be contaminated. All that was solid, cold and hard about her ‘80s persona seemed to melt into the mephitic jubilee humidity. Swaying like a sadly rehumanised replicant, her Grace had deteriorated upward into the Queen of a post-fordist, mid-austerity, slave population. ‘Slave to the Rhythm’ – our new national anthem.

The potential scandal of the song, so patent in the circumstances, ran a ring around its immediate producers and started going on behind their backs, or floated off into the fug, becoming suspended somewhere well above the deadheads of the array of VIP deadbeats. The encounter of sovereignty and slavery was flattened into a celebration of ‘our’ collective contribution to the declining days of a clapped out empire. For most of the high-end ticketholders, if it had any content at all, ‘Slave’ must have sounded more like a tribute to their own (individual-but-humanly-universal) entrepreneurial or political struggle to the top, their success in avoiding the lower rungs on the continuum of toil alluded to in the song. For others it may have sounded like a promise that ‘the rhythm’, if succumbed to sufficiently, would lead somewhere sexy and perhaps lucrative. But if you had eyes it was obvious that, after all, it all just lead to an encounter with John Major’s dead cod’s face. If you had ears, it sounded more like absolute reconciliation, accommodation to the grim present and the royal road leading down to it. Here was 60 years of unnecessary sufferation crowned by a hymn to hard work, an affirmation of ‘our’ passion for voluntary servitude, in a pageant by and for neo-peons. [1]

IV

Of course, with good carnivalesque logic, ‘slave’ was at least made briefly equal to ‘sovereign’, here. Grace’s lambent, flanging scarlet head dress made her a funkified Britannia stepped out of a 1977 £5 pound note (perhaps evoking Toyah impersonating her in Jarman’s Jubilee). A black figurehead for a currency and country now permanently in the red.

What life did remain in the song came from this flicker of well-contained subversion. At the same time this was transparently a bid for ersatz communion, the (all-excluding) inclusiveness of money. Multicultural/multi-racist UK could find a plausible image in Grace, queen of the willing slaves, icon of the (post)colonies, totem of the post-punks and of the post-liberal majority. (Slavery – not such a bad thing; welfare – a very bad thing: cutting welfare – officially the most popular thing the ConDems have done…)[2]

Perhaps every class has its reasons for projecting onto Grace’s labour programme, her master/slave narrative. Her performance seemed to pledge the fealty of the commonwealth to British capital, as if securing, standing for, the loyalty of the indigenous black population, not to mention the retro-funk-disco-loving tory hipsters of new Albion. Quite a hedge, the holy grail of social derivatives to yoke together and harmonize those contraries. She could stand for all Britannia’s hard-working people, black and white, rich and poor, representing and securing the future contribution of the UK’s ample population of second-class citizens. Keep it up, keep it up. Like Britannia on the back of a fiver here was a promise to pay the bearer on (effective, infinitely receding) demand whatever the claim happens to be worth at infinity. A promise on the one hand to sustain the spectacle of national accumulation, on the other to go on rendering up labour-power to the fictitious-pharaonic debt-pyramid-reconstruction programme so necessary to the putative growth and ratification of Britain’s precarious economy.

As the song comes to a close and Grace shouts out, 'We love you, our Queen', the Brechtian estrangement of the original curdles into definitive complicity. 'Slave to the Rhythm' has become a love song to the sovereign. Not the delirium of sexualised submission but submission to a sexlessness only outdone by the breeding of money. Windsorial replication. Cut from Grace Jone’s flaming headdress to John Major’s flat blank face, feel the blood drain from your entire universe. There were some lascivious moves in the performance that rendered it all a bit less hopeless -- how much is it appropriate for a scantily clad, hula-spinning 64 year old woman to love the Queen up? -- yet, though Grace seemed at times on the verge of crossing the line, sadly she demured. The rhythm's decorum was maintained.

V

Is there a silver lining to the diamond jubilee? The generally evident loss of aura attaching to Queen, country, and indeed capital coincides with the overbearing presence (as absence) of work. The fact that the union jack is so universal (as general and equivalent as £s) perhaps constitutes the precise possibility and limit of definitively overcoming the hold such national signs might still be said to have. If one ceases to fight the flag but rather flies it at the least provocation does one neutralise it? Or is it being re-envenomed, loading up on the ressentiment directed at the workless, disabled, and other backsliders in the speedy boarding channel to perdition? The mass hate for the non-working unwaged, the popularity of anti-benefits legislation, all these things suggest less than optimistic readings of the recrudescence of monarchism, however 2nd order.

As socialism continues to lose popular substance or claim as a locus of identity, while work seems as ineluctable as it is unattainable, does the monarchy, attached by some corporatist umbilical cord to the fortunes of labour, likewise grow weightless? If Grace had been substantialised, rendered all too human, has the Queen become weightless, taking over the post-modern role of replicant or human derivative, as ontologically deep as a scanned photocopy of Baudrillard's Simulations? Does the jubilee mark the point where no one wants to be ‘labour’ any more, but everyone believes (not unreasonably) that work is their only chance of survival. As such, rather than being a limit we have passed beyond, the old socialist affirmation of labour is replayed in an undead or zombie form. The return of the Queen coincides with this undead corporatism of the second-citizenry; the Queen of the refugees. Perhaps monarchy is, more than ever, the point where the fantasy of transcendence collides with the reality of subjection: Platonically, at the level on which reside monarchic simulacra and rockstars, I am a sovereign, identical with capital. One day I shall no longer slave, or at least I shall slave as a queen of the slaves, like Grace, elevated by my Queen. The current situation of having to work for nothing in the faint hope of future sub-subsistence exploitation is merely transitory and will lead at least to a rising standard of misery over one’s lifetime (cf, once again, the promissory structure of the steward-abusing Close Protection UK).

On the other hand, less bleakly, perhaps the panto of subjection is so second order it could at any moment flip over into a no-transaction-necessary trip through the windows of JD Sports? From riot to jubilee party to riot (prime). Every sign is equivalent, but none can be purchased even with hours of hard labour, so why work and wait in vain? The flipside of work without hope of payment is getting paid in full immediately without any work. While Grace was hula-ing in apparent subservience to capital and property my Jamaican neighbours were holding moderately lively bunting and bashment parties, while in the parks of Hackney the cops were pulling in the young black men for the usual crimes of hanging out, doing nothing, and waiting for their jubilee barbeques to start. Everybody takes part in the jubilee, everybody wants money, the rhythm is universal but that doesn’t mean its hold is perpetual or omnipresent, or will always take the form of subservience.

Observation suggests that the empirical (post-Jubilee) population will continue to play it both ways, a post-‘political’ mood which is in fact the most salient political fact of the times. As with the Olympics’ rogue Ambassadors who shamelessly brought forward their scheduled ‘best day ever’ from a couple of unpaid weeks in July 2012 to a few nights of delirious non-payment in August 2011, one has to consider the potential for any kind of carnival, however abject, to harbour a surplus ‘jouissance’ that gets beyond Lyotard’s old time masochism and enters a new dimension of collective wrongness. The bread and circuses economy (cf Hunger Games: we all live in districts of the global Panem) means people seem to invest a little in any kind of holiday, whatever the branding and the fallout, they take what they can get from the superficial bounty, though they are probably well aware that mostly it isn’t for them, and indeed depends on their being not only passed over but looted a little more.

VI

If Slave to the rhythm is the new national anthem, what was it the old one said about slavery? ‘Rule Britannia, Britannia rules the waves, Britons never ever shall be...’ Oh, ok, they might be and/or have been slaves (the jingle was written almost a hundred years before the formal abolition of slavery in 1833, suggesting a persistent tendency to bullshit), but today they're slaves to the rhythm and that's what counts.

So what is, or was, the rhythm? Beyond the Lyotardian suggestion that the specifically capitalist form of slavery requires one to enjoy being uprooted, alienated, exploited, is this a song about capitalism as – once upon a time, at least – in some way emancipatory? Or is it better understood as capital’s swan song, a premonition of its descent into a new form of slavery in which ‘free labour’'s dialectical tensions and possibilities collapse in on themselves? On the one hand, the rhythm evokes the rationalised wage slave, as opposed to arrhythmic, yet-to-be-Taylorised slavery proper. It’s the (old) new thing, the form of free labour which at least creates (created) a new possibility for full emancipation, radical chains. Is this 'chain gang song' more focused on the production line composed of free labour as opposed (and preferred to) the corvée? Could Grace’s jubilee turn remind us of the lost potential of her own erstwhile ‘meta’ alienation and abstraction as a post-punk performer?

This is complicated, but the gist is that Jones' postmodernism was itself already a second order recycling of a certain modernist nihilism, the Tafurian reading of Benjaminian mechanical reproduction as emancipation from aura, a stripping down of the bourgeois subject prior to revolutionary (or simply fordist) collectivisation. But the postmodern frisson of a new fragmentation and flexibilisation of identity was at the same time the cutting edge of restructured and extended production time. It might have looked like a break from the fordist regime, but the post-punk moment degenerated in to the 'Corporate Cannibal' condition Grace indicts (less gracefully) in a more recent, self-penned, release. Not only was postmodernism an extension, acceleration, and intensification of the logics of modernism, fordism, taylorism, rationalisation, reification or what you wil. Their extension into subjectivity, into expressivity, culture and 'communicativity'. It also marks a new composition of value achieved by reengineering the ratio of reproduction to non-reproduction, an extended form of devalorisation in which, increasingly, collective labour-power's cost is lowered by abbreviating or aborting its reproduction. As an import, like so many others, from the West Indies, Jones is again emblematic of the gradual shift of the UK and global economy from reliance on expanding productivity to expanding non-reproduction (cf a forthcoming review by Loren Goldner of Nicholas Comfort's book on the decline of UK industry during Elizabeth's reign). Reconceived as such, the Island of freedom and experiment of the post-punk/disco moment was an at best temporary autonomous zone, a utopian space in which Grace's gang/masters made a cubistically fragmented and hard-edged icon of liberation out of her at the same time that capital was engineering a new kind of primitive accumulation. Indeed her career embodies this as much as any Jamaican artist of the era, perhaps more than most as a woman subject to much male manipulation, depicted as an object rather than subject of the musical and graphical means of production. Her post-disco manumission was an ambivalent emancipation at the hands of the most advanced pop and fashion technicians.

Listening again I note that 'slave' is a verb, not a noun, in the song. It’s an imperative naturalised as a descriptive. The song at once records and prescribes eternal bondage, from 'ancient time' to 'power line', there will always be 'men who know /Wheels [and hula hoops] must turn, to keep the flow'. Accumulate, accumulate, this is Moses and (his shit hot backing group) the Profits – continuous activity, productive or not, ensures accumulation - 'build on up' – or at least its facsimile. If the song anticipates some new and better kind of slavery it also projects its capitalist form back across time. As such it's a kind of ‘robinsonade’, as Marx terms the economists' fairy tales of accumulation, a survivalist fiction hallucinating capitalist labour relations back across history, although with the difference that 'Slave to the Rhythm' insists on and celebrates collectivised labour whereas the economists mostly forget about this crucial prerequisite for capitalism. The singer (Wo/man Friday?) of 'Slave to the Rhythm' is part of the chain gang, not one man's servant but the slave of a socialised – industrialised – labour process: 'don't break the chain/Sparks will fly when the whistle blows,/Never stop the action...' Crucially there is no ‘I’ in the lyrics, Jones is not only a construct but this (not uncommon, but rather universally unstated industry standard) estrangement is built into her musical persona and performance. Or at least it was: now it seems flattened into compliance, rather than an unsettling or even confrontational disjuncture; ‘we love you, our Queen’ is a scary development/decline: still no I, but a subsumption under the community which previously had the good sense to be freaked out by Jones and which she seemed to keep always at a distance, as if waiting to attack; blackness as menace, defused. This baring of the collectivisation process in the aesthetic does not indicate emancipation of the singer as worker, of course. In a way one could describe postmodernism/post-punk as the moment where the devices of estrangement become tools, options, of integration, from pop to finance. The glimmer of emancipation in Slave to the Rhythm is nothing if not paradoxical, precarious.

Returning to our robinsonade, Trevor Horn, who has a writing credit as well as producing the original track, was overseeing Grace's musical development for Island records, and shaping her 'Island Life' along with the other ‘men who know’ at the time. So the black Jamaican woman (styled by the French graphic designer Jean-Paul Goude) sings the universal work song, scripted and, using cutting edge digital tech, programmed by the white British middle class male producer – to 'our Queen', the globalised sovereign of post-colonial reflux, restructuring and non/reproduction. The performance seems to bring everything full circle (a circuitous vicus of recirculation, as Joyce would say). It’s a kreislauf of capital or spiral scratch in the black vinyl of human history from 'ancient time' to the atavistic present... Slavery as the human condition, something which answers to a deep, bodily imperative, the inner slavedriver of the passions. Biopower and labour-power, forever. But it’s not serious, it’s not deep. It’s a pose, it’s a style, it’s a mode of sexuality. It’s a front or second order sign. Slavery at once empassioned and detached. And it’s not really about a display of work as strenuous, it’s (only) digital Stakhanovism.

The way the song slinks around, slides into oddly suspended interludes, the effortlessness of the delivery -- she can sing it while hula-ing and not miss a beat or strain a phrase -- signifies infinite grace under pressure, a transcendence of the very conditions the song immortalises. The necessary detachment and poise for postmodern flexi-labour, etc. So as a work song it's pretty much of its time - work has been so decomposed and dematerialised that – ideally, at least – one can do it with complete impassivity. Especially if one is the producer -- executive, or speculative. Working without breaking a sweat. The singer is just the mouthpiece or figurehead of a process of sonic and visual collage, of a cool disintegration and re-inclusion of every part of the live-working subject. Like Britannia, Grace's job is to give a local habitation and a name to a socialised, decentred form of production, to turn the precision breakdown of the self enabled by the high-tech, no-wage post-fordist division of labour into a passionate enterprise, capital with a semi-human face. As such she represents not only the UK but also the labour-process more generally as an ineluctably enjoyable servitude (‘I love my job’ as the telephone box cards used to say). The slavery which Horn and Goude's supervisorial and 'creative' mastery presupposes only returns aesthetically in the lyrical and musical allusions to a sexualised immachination. Slavery is 'managed' by the song as a second-order futurist fetish of (no longer) 'mechanical reproduction'. 'Slave to the Rhythm' as anthem of digitalised and financialised production. It’s all part of the process which has now killed off vinyl production in Jamaica and lowered the wage ceiling there and globally. 'Keep it up, keep it up'. The perfect message for a jubilee designed to at once distract from and legitimise our eternal debt and bondage to Queen and country. From Studio 54 glamour to a drizzily austerity jubilee, the song has come a long way, but it is poised, paralysed, stunned perhaps, between a downward spiral into work without reproduction (of the worker) and reproduction (of the capital relation) without work.

CREDITS & FURTHER READING:

DH - for perpetual thought provocation and post-Keynesian percipience; MH for pinning punitive accumulation, drawing my attention to 'the post-liberal consensus' mongers, and parsing all the Terms & Conditions:

http://wealthofnegations.files.wordpress.com/2012/...

FOOTNOTES

[1] The etymology is illuminating: pageant has signified the play in a cycle of mystery plays; a manuscript, stage, or scene of a play; a moveable scaffold – with some connection to the etymological sense of ‘stake’; as well as the more recent and familiar ‘showy parade, spectacle’. Every spectacle is a stake, a missed opportunity for a scaffold, a pre-scripted page in a cyclical play that keeps getting re-produced.

[2] The new (pro-)slave morality is all about negating all the dangerous and exciting aspects of Grace Jones’ direct enunciation of ‘slave labour jouissance’ (‘the chain gang song’) and keeping the slave labour. This is a rather differently sexualised conception of work, work not as sexy, as a perversion, basically, but as ‘good’ and intrinsically moral. David Goodheart in the FT gives us an unwitting (indeed witlessly) chilling glimpse into this new political horizon:

‘Post-liberalism does not want to go back to corporatist economics nor to reverse the progress towards race and sex equality. Britain is a better place for these changes.

But post-liberalism does want to attend to the silences, excesses and unintended consequences of economic and social liberalism – exemplified in recent years by, respectively, the financial crash and last August’s shocking riots.

With their emphasis on freedom from constraint the two liberalisms have had too little to say about our dependence on each another. They have taken for granted the glue that holds society together and have preferred regulations and targets to tending to the institutions that help to shape us. As the philosopher Michael Sandel puts it: “In our public life we are more entangled, but less attached, than ever before.”

…

Many of these people hear politicians speaking a different moral language from them, about abstract rights and communities in name only. The welfare state is a particular point of conflict. There is an increasing reluctance among middle and lower income citizens to pay their taxes into today’s welfare state. They do not believe in universal welfare, they believe that welfare should go to those who have paid into the system or who deserve to be supported by the community.

These are the people that post-liberalism can win back to politics. Not just by managing the economy and public services competently, but by reconnecting with an idea of moral community.’

‘Welcome to the post-liberal majority’, David Goodhart, May 11, Financial Times, http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/a992778e-9aa4-11e1-9c98-00144feabdc0.html#axzz1xfV9xZz2

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com