RIOTING WITH REASON: FROM ENGLAND TO SWEDEN AND BACK AGAIN

Why do English sociologists and politicians find riots so much more explicable when they happen overseas? Nina Power finds an international logic behind 'national' expressions of rage

The idea of the nation, so beloved of governments and right-wingers everywhere, also holds the steady gaze of the media, always keen to hand-wring and pronounce upon how the social compact is being eroded by malign, usually ‘external’ forces. But somehow it seems much easier for newspapers to understand what is happening elsewhere, or at least to try to explain it: thus in the case of the Stockholm riots, British papers - where they have covered it at all - have been surprisingly sociological. These riots are a direct result of police harassment, youth unemployment, racism and economic inequality. They were triggered, as so often, by a police killing, and the angry response that followed - burning cars, property damage, attacking a police station - is a rational reaction both to the killing and to the larger socio-economic situation. Despite its (rapidly-dwindling) reputation for generous welfare provision, high living standards, tolerance and other Scandinavian stereotypes, Sweden has now joined other European countries - France and England - in experiencing riots in their cities within the past decade.

This is the story the UK media feels it can tell about what is happening in Sweden, and depending on the political persuasion of the outlet, it will focus on one or other of the ‘causes’: the original killing of the 69-year old man, or youth unemployment, the absence of housing, or rapidly widening economic inequality (the fastest of any OECD economy in the past 25 years we are told), or problems around the ‘assimilation’ and ‘integration’ of immigrants, or everyday police violence and racism. But everyone agrees on one thing - it is possible to understand why these riots are happening. But how strange! When rioting broke out in London and other English cities in August 2011, following the police murder of Mark Duggan in Tottenham, an economically-deprived part of North London, it was as if all explanations had suddenly been taken away: ‘now is not the time to explain, now is the time to act!’, ‘we don’t care why this is happening, we just want it to stop!’, ‘more police now!’, with the prime minister, David Cameron weighing in with the mighty sociological suggestion that this was ‘criminality pure and simple’. How curious that it should be so much easier for the British media to comment on the Swedish situation than it was to comment on its own! But this is how the fantasy-logic of nations works: ignore the larger picture, shrug off global trends and patterns, stress the singularity and specificity of events so that it becomes impossible to understand how unemployment in certain cities, say, relates to the global economic crisis. We even have this admission from the BBC: ‘But there does seem to be a particular Swedish problem. The country had a reputation for generosity and an especially welcoming attitude but now something is clearly going wrong.’ (http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-22650267) - the implication perhaps being that Britain has a reputation for being unkind, so that any riots that follow are perfectly well to be expected in such a cruel and inhospitable environment.

But of course there are certain trans-national makeshift ‘explanations’ that do shift from country to country: it’s all the fault of the families! Lack of male role-models! Lack of willingness to learn English ... I mean, Swedish! These reactionary discourses play into the hands of those who would seek to profit from the separation of the population into ‘us’ and ‘them’ by conveniently ignoring the rather more obvious pressures of unemployment, poverty, racism and having nowhere to live. The discourse then becomes one of ‘violence’, and just as Cameron and other British politicians couldn’t fall over themselves fast enough to condemn the ‘violence’ of the rioters two summers ago, we have Fredrik Reinfeldt’s statement: ‘ We have groups of young men who think that that they can and should change society with violence. Let's be clear: this is not okay. We cannot be ruled by violence’.

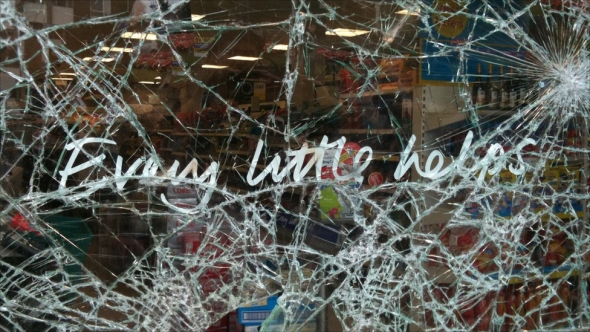

In the years since students took to London streets and damaged the Tory party headquarters in protest at the tripling of tuition fees to £9,000 a year, and the many protests that have followed, including the riots of 2011, the question of violence, who has the monopoly on it, and the way the media uses this emotive term has come into sharp focus. What was the smashing of a few windows compared to the destruction of the future of many? How is it possible to compare the burning of a few cars to being daily harassed and insulted by the police? Where a person has been killed by the state, what reaction could possibly be sufficient to express the anger and pain induced? Can politicians adequately empathise with people who have been locked out of work, housing and society at large? And yet the ‘violence’ that scandalises the media is always violence against property, never the daily violence against the person, even where that person has been killed. ‘We cannot be ruled by violence’ says Reinfeldt, but people are, continually: why feign surprise when they start to fight back?

Riots are always an unexpected shock – until, that is, they happen. Which they do, and will do increasingly so long as the project to privatise, financialise, monetise and securitise human life continues. These measures are predicated upon and require the widening of economic inequality, the very factor that will always generate social unrest, especially if combined with police violence and racist abuse. A short while ago I visited Sweden and spoke to people who were shocked to hear about library closures, the selling off of the National Health Service and other attacks on what minimal ‘public’ and ‘social’ life is left in Britain. Some found it difficult to imagine such things happening in Sweden, and even harder to imagine any kind of uprising in response: but here you are – this is not a ‘Swedish’ problem, or a ‘national’ question but an international and a human question. It is not too late to understand why people are angry – and all you need to do is look to Britain to see a perfect example of what not to do next.

This article was written for DN Kultur:

http://www.dn.se/kultur-noje/debatt-essa/ilskan-i-...

On the UK riots in August 2011:

http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2011/aug/08/context-london-riots?INTCMP=SRCH

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com