History has Failed and will Continue to Fail

In early summer 2001, violence exploded across several Nothern English towns. For many, the riots appeared to come out of the blue, but the building blocks of an explanation were soon in place - to be repeated by newspapers, TV, community spokespersons and state authorities. In the wake of events, Matthew Hyland reads on from 'irrational, mindless thuggery' to 'race riots' and representation.

Through April, May, June and July this year, large groups of young 'Asians' have sporadically but efficiently fought police (and a few sub-fascist white opportunists) in the streets of towns across the North of England. The inevitable outcry of reasonable opinion has come in a variety of styles, but it has also revealed a remarkable consensus. Community leaders, columnists, police chiefs and politicians each spoke according to type about mindless thuggery or a tragically misguided collective outburst, but all agreed that the rioters' behaviour was somehow irrational. No doubt this shared certainty across the presumed political spectrum tells us something about social spectatorship and bourgeois thinking; what it indicates more urgently, though, is quite how rational the action of the 'violent minority' may have been.

Perhaps the single silliest aspect of the coverage has been commentators' lament that an almost understandable reaction to organised racist provocation was subsequently 'turned against' the police, as if the cops were little more than unfortunate bystanders. Of course this could hardly be further from the truth. In Oldham, for example, the police's response to an evening's violence and intimidation by a specially bussed-in National Front/Combat18 gang was to turn up in riot gear, arrest Asian men, and try to disperse a crowd of angry local residents. As Arun Kundnani points out in his important essay 'From Oldham to Bradford: the Violence of the Violated' (to be published in October 2001 in the Institute of Race Relations collection The Three Faces of British Racism) the police weren't 'defending the rule of law', they were acting as an invading army, and as such they were driven off the streets, dogs, armoured vans and all. It would be too much to expect left-liberal journalists to recognise the police as part of a racist state apparatus not just when 'unwitting prejudice' gets the better of them but when they're doing their job properly, but apparently it never even occurred to them that young Pakistanis and Bangladeshis in one of the poorest parts of the country might see things that way. These earnestly anti-fascist souls flatter the far-right groups extravagantly in imagining that all the fury of the revolt was the product of their sorry manoeuvring.

Oldham and Bradford in particular were notable for the rioters' practical effectiveness - holding territory, repeatedly driving back police attacks, and avoiding large numbers of arrests - and also for the risks taken by those involved. These two aspects are obviously not unrelated, as the counter-example of the London Mayday debacle shows. The self-styled anti-capitalists agonised for weeks before and after the non-event over the tension between material and symbolic politics, or what's effective physically and how it would be represented. In Burnley, Leeds, Stoke-On-Trent, Bradford and Oldham this debate seems never to have been scheduled. Simply doing what was necessary to hold off the police meant abandoning hope of a 'fair hearing' from the BBC or the Guardian. Indifference to being slandered on TV as criminals, along with the resolution to deal with serious police violence, tends to come with the realisation that the machinery of political and media representation isn't an open forum for communication, but a weapon used by the social subject enjoying access to it against others that don't. At this point those for whom the arsenal is unavailable attempt, quite rationally, to destroy the physical conditions it's used in. The complete failure of the most sympathetic media and mediators to guess at any of this confirms the wisdom of absconding from their skewed agora.

The current unprecedented distance between representation and social reality is especially evident in public discourse about 'racism'. Five or ten years ago the word was barely heard in polite discussion. Now it's the subject of almost daily homilies from politicians and journalists. This new visibility, however, has come at the cost of something approaching a complete reversal of the term's meaning. The 'Stephen Lawrence Report' by eporting judge Sir William Macpherson of Cluny was central to this process. Macpherson's report can be seen as symbolic of the whole process whereby the evil of 'racism' has become a ubiquitous feature of public discourse while the term is drained of its social and historical meaning. A Home Office green paper explicitly tied the report to the notorious Asylum and Immigration Bill as the two faces of New Labour 'anti racist' policy. The report popularised the term 'institutional racism', first used in the 1960s by black student leader Stokely Carmichael and the Black Panthers to designate the systematically racist policies of a state apparatus. Macpherson, however, takes pains to emphasise that 'the contrary is true'. He redefines 'institutional racism' as a purely personal psychological defect that happens to be shared by a large number of people. It's a question of unwitting bigotry in 'the words and actions of officers acting together', simple ignorance to be cured by hours of quasi-therapeutic training. This piece of semantic juggling actually makes it more difficult than before to address publicly the racism administered by institutions in their normal functioning, as the only language in which this could be done has been hijacked and turned to innocuous ends. The report's complete failure to deal with a non-psychological fact like the number of black deaths in police custody demonstrates this, as does a recent report on the Crown Prosecution Service by lawyer Sylvia Denman. The CPS was found to be 'riddled' with institutional racism, meaning it often treats its own black and Asian staff unfairly. Yet the huge and systematic racial disparity in suspects' chances of being prosecuted (black and Asian defendants are four times as likely to have their cases thrown out in court, implying a roughly corresponding ratio of doubtful charges gone ahead with by the CPS) wasn't even mentioned.

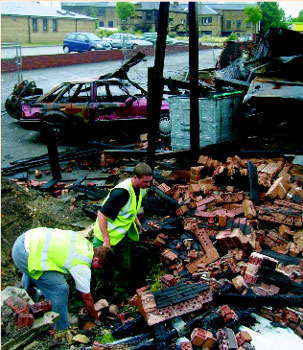

Oldham may have witnessed almost the first practical fruit of Macpherson's psychologizing zeal (I say 'almost' because in the last year or so we've already seen the law against 'racial hate crime' in action: a black man fined 150 pounds in Ipswich crown court for supposedly calling some cops 'white trash', and protestors prosecuted under 'racial aggravation' laws for hurting American soldiers' feelings by burning a US flag). One of the judge's most important and strangest recommendations is that a 'racially motivated incident' be defined as 'any incident which is defined as racist by the victim or any other person' (emphasis added). Not surprisingly, police statistics on the apprehension of 'racist crime' have improved dramatically since the words' meaning was opened up for spontaneous redefinition by any passerby or policeman, eliminating the tiresome notion that the perpetrator or at least the victim should be the judge of motivation. Thus Oldham police felt quite at liberty to treat the beating of 76 year-old pensioner ('and war veteran!' screamed the quality press) Walter Chamberlain by Asian youths as 'racially motivated', despite the complete lack of any evidence to this effect and the insistence of the victim and his family that it was not the case. Before long the BNP were marching around the town with pictures of Chamberlain's battered face on placards. The new in-definition of 'racist incident' also generated the infamous statistic purporting that '60 per cent of racist attacks in Oldham are carried out by Asians against whites', first published by the Oldham Evening Chronicle, whose offices were shortly afterwards consumed in the (real not symbolic) flames of Asian indignation.

The psychologisation of race and racism can be seen as part of a wider tendency in government policy, scientific practice, academic and media discourse. Increasingly, these apparatuses of representation seek to manage social problems through intensive and pre-emptive monitoring of individuals seen as presenting 'risks', rather than waiting to judge particular actions or sets of circumstances (as in a traditional criminal trial or benefit claim, for instance). 'Risk', in the form of criminality, 'anti-social' tendencies or personality disorder, is presumed to dwell as a quasi-pathological tendency within the individual. It's only a matter of time until certain people actually commit a crime or have a psychotic 'episode', so why shouldn't the state intervene before they do something? We've already seen 'Community Safety Orders' allowing judges to turn any future acts like spitting, pissing or loitering into serious criminal offences for specific individuals who haven't been convicted of anything yet. Compulsory drug tests for everyone arrested are already underway in Hackney and are coming soon to the rest of the country, as is a permanent DNA archive of potential criminals. David Blunkett's first proposals as Home Secretary (taken from the Halliday report on sentencing reform) include 'Acceptable Behaviour Contracts' for teenagers, police powers to impose curfews, compulsory work or drug treatment on unconvicted young people, and provision for 10-year supervision orders after completion of sentences. The forthcoming and deeply sinister Mental Health Act (see 'Mad Pride', Mute 20) is another part of the picture.

Any critique treating these moves towards personalised social control as a 'civil liberties issue' is totally inadequate. The new techniques are designed to contain the disruptive potential of the social class with least to lose. Any doubt that racial minorities will be affected disproportionately should be dispelled by the first examples of the new thinking put into practice. A recent Lambeth police experiment called 'Operation Shutdown' saw 'prominent or development nominals' – people 'known' to be 'involved with crime', although they hadn't necessarily ever been convicted and weren't wanted for anything at the time – stopped in the street, surrounded and very publicly videotaped by vanloads of cops. The number of black nominals was as high as Lambeth's grotesque figures for regular stop-and-search would lead one to expect. Merseyside police, meanwhile, are pioneering the DNA archive scheme by taking non-consensual samples from anyone reported in connection with a 'racial incident'. In general, the rise of 'informal justice' Ð treatment of alleged criminality outside the courts Ð is disturbing: as the already mentioned high rate of black and Asian acquittals shows, in at least some cases courts' slow examination of what has happened corrects the criminalisation of certain subjects based on who they are. (The example that comes most easily to mind is that of Delroy Lindo, fitted up 20 times by Haringey cops over a couple of years, with the charges always thrown out in court.)

Arun Kundnani observes that the recent rioting was 'ad hoc, improvised and haphazard', in contrast to the organised community self-defence seen in 1981, when the Asian Youth Movement burnt down a pub in Southhall where fascists had gathered, or when members of the Bradford United Youth Movement were arrested for making petrol bombs in response to fascist attacks in the area. Certainly, it would be grotesque to twist recognition that this was the desperate action 'of communities falling apart from within as well as from without... the violence of hopelessness' into glib celebration of its spontaneity. Nonetheless, it may be that the widely deplored 'excess' or 'incoherence' of the riots as a 'response to racism' reveals a feeling among at least some participants that the target for their anger, the set of conditions to be destroyed, can't be reduced to a single enemy or injustice. The risible failure of 'community leaders' attempts at mediation reflects many young Asians' complete disdain for these state-funded patriarchs' claim to represent them. It may also suggest that what was sometimes claimed for street battles of the 1960s (by the Situationists for the Watts rebellion, and, with flagrant disregard of what actually happened, by various romantics for May-June '68 in France) might apply here: that no particular concession from above would have sufficed to content the crowd, to send them home newly reconciled to their lot. The idea that the violence was 'excessive' and apolitical patronisingly presumes that young Asians don't know that in their experience of poverty and racism they're confronting a historical totality, rather than an isolated problem that the present system could choose to solve or not. For instance, the fact that Pakistani and Bangladeshi communities across the Pennine hills are among the poorest 1 per cent of Britain's population is partially related to the economic need to send money back to families at 'home'. This situation is inseparable in turn from imperial Britain's destruction of the Indian textile industry and the establishment of the Lancashire and Yorkshire mill towns as prototypical Export Processing Zones spinning cotton grown in Bengal, among other places, into cloth to be sold back at a profit to the empire. Eventually Pakistani and Bangladeshi labour was brought in to do night shifts disdained by the existing workforce, until, as Kundnani puts it, '[t]he work once done cheaply by Bangladeshi workers in the north of England could... be done even more cheaply by Bangladeshi workers in Bangladesh.' So cheaply, in fact, that their pitiful earnings have to be subsidised by relatives now in precarious service sector work or on the dole in England. Thus in the everyday constriction of their lifeworld, the mill towns' Asian youth take on the weight of colonial history as well as globalised capital's ability to generate wretched 'necessity'. Even if today's desperation might somehow be overcome within the present social horizon, there is a sense in which the past cannot be rectified, only avenged. It's significant that the few young Asians interviewed in mainstream media after the riots spoke not only of their own obstructed futures but also, without distinguishing past from present, of what their parents' generation endured. 'If they could get good jobs here why would they be driving cabs?' asked one.

The debate over whether race or class was the 'reason' for the conflict seems absolutely sterile in this context. As certain commentators never grow tired of observing, the white working class suffers too, especially in de-industrialised Northern towns. The likelihood that the ultimate sources of everyone's misery might be the same, however, doesn't alter the reality that things are quantitatively worse for certain racial groups, for reasons which may not be tangible in the eternal present of newspapers and TV but which with a little attention to history are anything but mysterious. Ultimately race and class are inseparable: racism is most real in the intensified application to particular ethnic groups of expropriation and control techniques used against the entire working class. Conversely, class is always lived in a racialised way: expropriation and control are experienced differently according to (plural, contestable) attributions of 'race'. 'Ethnic minorities' have no choice but to be aware of this, whereas among white Europeans only those peddling the absurd idea that life is worst for whites seem to acknowledge it. Most who have the luxury of being able to do so like to imagine, no less absurdly, that whiteness means racial neutrality. Once again, Oldham offers plenty of examples. The most recent available Home Office figures (1998) show the rate of unemployment in the town at 4.3% overall and 38% for Pakistanis and Bangladeshis. Housing statistics, meanwhile, record that 13% of homes in the area were 'statutorily unfit for human habitation', with another 28% 'in serious disrepair'. These privately-owned ruins were concentrated in the largely Asian areas, also noted for high rates of household overcrowding. The situation was hardly accidental. Paul Harris and Martin Bright in The Observer ('Bitter Harvest from Decades of Division', 15 July, 2001) recall that young men coming into Northern textile towns from South Asia in the 1950s were often kept out of council housing by a two year residency condition operated by local authorities. Consequently they moved into the most run-down areas with the cheapest rents, and '[a]s the first Asians moved in, the whites moved out. As more Asians followed, they were housed nearby, often because in their own Bangladeshi or Pakistani quarter they felt safer from attack from the whites.' Not surprisingly given their economic vulnerability, many young Asians sought to buy their own property as an investment, with the result that they became owner-occupiers of small, dilapidated houses unwanted by whites, without the money for repairs or relocation. Although these phenomena were the subject of research by Pakistani sociologist Badr Dahya as early as the 1970s, little has changed in the meantime. In 1993 Oldham Borough Council was found guilty of running a segregationist housing policy, moving white residents into new suburban estates where Asians were often denied accommodation and faced harassment and violence if they did get in. Hence they stayed in their damp, overcrowded terraced houses, 'a community penned in' as further white flight kept property prices low. Confinement of ethnic groups in single areas 'naturally' led to educational segregation; as a generation grew up unaccustomed to ethnic mixing, the limitation of Asians' mobility could be portrayed in local and national media as 'self-segregation', or even the deliberate creation of 'no-go areas' for whites.

A 'race riot', then, is always already a class riot, although that doesn't mean it makes no difference whether or not racial groups stereotyped as enemies are fighting side by side. This is said not to have been the case in the Northern towns (unlike Brixton in 1981, '85, '95 and 2001 or LA in 1992), but 'Asians vs. whites' is nonetheless a misleadingly vague way to characterise the sides involved in the fighting. The question of collective subjectivity needs to be looked at closely here. As the difference between its meanings in, say, Manchester, San Francisco and Moscow (or now and 2,000 years ago) suggests, 'Asian' is a concept with unstable boundaries, most often used for convenience by people who don't see it as referring to themselves. There's little reason to assume that many of the youths involved in the recent clashes would have thought of themselves primarily as 'Asian'. Guardian journalist Faisal Bodi has drawn attention to hostility between groups of Muslims in the Northern towns: not only between Pakistanis and Bangladeshis, divided by the war that separated East and West Pakistan and created the state of Bangladesh, but also among Pakistanis, between Pathans, Punjabis and Kashmiris living in separate clusters in the same towns. These forms of ethnic and linguistic isolation, which as Kundnani notes reinforce the power of community patriarchs within their own clans, have a lot to do with the identity politics in practice in the race relations system, with money for ethnically exclusive centres and language support 'pouring into' the towns, chiefly benefiting 'people whose livelihood depends on being linguistic intermediaries between minority communities and local authorities', as Bodi points out. In these circumstances competition between areas for funding further exacerbates tension by giving the (fairly accurate) impression that one ethnic sub-group's gain is another's loss.

Such is the institutional hegemony of identity politics and the moral authority of victimhood today that the BNP has adapted its rhetoric correspondingly, emphasising a 'need' to preserve the fragile cultural and biological identity of British whiteness. Disingenuously sidelining the questions of class and power in trying to present 'whiteness' as an ethnicity 'like any other', this discourse could be said to take the cultural studies separation of cultural self-identification from its material basis to its logical conclusion. A more pompously world-historical version of the same kind of thinking is offered by Horst Mahler, once of the Red Army Fraction, now spokesman for Germany's xenophobic New Democratic Party. In the '70s, he says, the New Left (and the RAF as its armed wing) were fighting for national self-determination for 'third world' countries like Vietnam and Palestine. That, he insists, is just what the 'left-wing' NDP wants now: 'self-determination' for Germans in Germany, Turks in Turkey, etc, as if Germany, Turkey et al were timeless natural entities.

Yet the violence in Oldham, Bradford and elsewhere clearly demonstrates what the politics of identity always fails to recognise: that material necessity leads the way where (self-) representation may or may not confusedly follow. When confronted with the need to defend themselves and their space against aggression from police and fascists, Pathans, Punjabis, Kashmiris, Bangladeshis and others acted together with unquestionable effectiveness. Bodi points to ecumenical, cross-community Muslim projects in housing and youth work as potential roads out of identity ghettoes; multi-denominational street-fighting against uniformed and freelance racists can be seen as another. This is not to say that in the course of the turmoil the rioters consciously assumed a new, shared 'Asian' or 'Black' subjectivity. But even if each small group of friends and family had been concerned exclusively with its own narrow interests (and there is no reason to believe that this was so), all were obviously aware that their own interests, in the most immediate, concrete sense, could safely be pursued only through cooperation.

Nor should it be taken for granted that the nameless, provisional collective subject that seemed to flicker into being in the riots, if only for a few hours at a time, existed solely in reaction to white racist aggression. Both the persistence of the violence over four months and such supposedly gratuitous but in reality eloquent and political acts as the destruction of a BMW showroom suggest that the young men wanted not only to defend their communities, but also to assert their own power and autonomy, in however indeterminate and limited a way. Well-meaning commentaries that reduce displays of force to unruly forms of protest deny 'subaltern' subjects a capacity for independent action: even the most violent protest, conceived as such, engages in a dialogue initiated by the more powerful side. By contrast, the very failure of the mill town rebellion to specify political 'demands' from a recognisable subject position has, in a highly problematic way, made the young 'Asians'' self-assertion an unanswerable fact. Perhaps this un-identifiability of a subject which nonetheless refuses to be ignored, this conspicuous neglect to address or be addressed by the organs of representation, contributed to the horror in which leaders of local communities, national politics and public opinion were united.

Matthew Hyland <matthewhyland AT hotmail.com> is co-compiler of Wolverine, the journal of Childish Psychology [http://wolverine.c8.com/], and is one seventh of the Mean Streaks.

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com