Objective Phantoms

The Passive Vampire, Romanian surrealist poet Ghérasim Luca's recently translated book, brings objects and desires into intimate contact, with unexpected results. Review by Kenneth Cox

Ghérasim Luca's Le Vampire Passif has for many years been surrounded by an aura of mystery, like a ‘forgotten' or lost grimoire of surrealist writing; a book that, like its author, has had something of a ‘phantom existence'. First published in Budapest in 1945, by the appropriately named Éditions de l'Oubli (‘Forgotten Books') - written in French, and not his native Romanian - in an edition of only 460 copies, the book was not republished until 2001, by José Corti. It was not only its inaccessibility that created the book's legendary status, and not only amongst that minority readership interested in surrealism, but the personality of its author.

Born Salman Locker in Bucharest in 1913, the son of a Jewish tailor, it wasn't until much later that he became Ghérasim Luca. Drawn to poetry and the Romanian avant garde, when Locker was about to publish his first text, the pseudonym ‘Ghérasim Luca' was suggested by a friend, which he promptly used. Only later did he learn that his friend had stumbled across this name by chance in an obituary. In 1940, together with Gellu Naum, Dolfi Trost, Virgil Teodorescu and Paul Paun, he founded the Romanian Surrealist Group, following a visit to Paris in 1938 where, through fellow Romanians Victor Brauner and Jacques Hérold, he had met the French surrealists - a decisive encounter. Although in existence for only seven years, cast adrift in clandestinity throughout WWII and mostly remaining in obscurity ever since, the Romanian Surrealist Group was nonetheless one of the most explosive, original manifestations of surrealist thinking and practice. Throwing down the gauntlet with their pivotal statement, composed by Luca and Trost, The Dialectic of Dialectic: a Message to the International Surrealist Movement, they set out to challenge any slide into complacency that might result in surrealism's discoveries being absorbed into means of cultural production only, to prevent it ‘sinking into a hackneyed Romantic idealism'. Their declaration makes the uncompromising demand that surrealism remain in a condition of perpetual revolution, through taking a radically dialectic standpoint of continuous negation, and further, the negation of that negation.

In 1952 Luca moved from Bucharest to Paris, the city he loved, where his poetic researches were mostly of a solitary nature. Perhaps best known for his poetry, with its hermetic wordplay exploring the morphology of language, breaking down and rearranging its constituent parts to uncover new meanings, Luca was described by Gilles Deleuze as the greatest living poet writing in French. Having spent over 40 years in France without papers, he was evicted from his apartment in 1994, along with all the building's tenants, victims of ‘urban renewal'. At the age of 80 and unable to accept his new situation, Luca committed suicide on 9 February 1994 by drowning himself in the Seine - a poet's death, his body being found exactly one month later, an event curiously foreshadowed in a text from 1945, La Mort Morte (Dead Death), composed of five ‘suicide notes'.

The Passive Vampire itself is an object that is incredibly difficult to describe, as elusive as its subject matter, being a concoction of theoretical enquiry and deeply personal observation, mixing poetic prose and psychoanalytic investigation. On the surface, it deals with the creation and exchange of (highly personal) surrealist objects, illustrated throughout with enigmatic photographs, presented as pictorial evidence in such a way as to place the book in a lineage stemming from André Breton's Nadja. In places it possesses a distinct lyrical quality, most likely inspired by Lautréamont, but rather than taking a delirious plunge into the imagination's depths through any purple prose, Luca writes with a disarming honesty and directness in describing and interpreting events.

The book falls into two distinct sections, the first of which is concerned with what Luca terms the ‘Objectively Offered Object' (OOO), and describes the circumstances surrounding a number of these composite surrealist objects, each made by combining found or chosen individual items. These composite objects were made by Luca in order to be given, as a means of revealing the hidden relationships between subjects, through an ‘active collective consciousness' that is very much analogous to dream. The giving of such OOOs is differentiated from the giving of ordinary presents, an act which has been reduced to mere convention or habit and from which the force of desire has been drained. These objects, on the other hand, are made as vessels for desire and as a means of deciphering unconscious messages, which for Luca are signs that, in their combinations and interpretations, primarily carry highly charged erotic meanings. The OOO is thus somewhat like a magical spell that both describes a desire and at the same time reveals it, and even perhaps invokes it, as if causing an event to happen. And as the truism goes, you should be careful what you wish for.

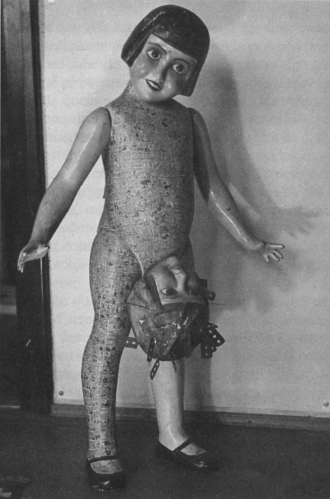

Ghérasim Luca, The Letter L

One such object, entitled ‘The Letter L', is constructed from an old, wooden child's doll found in an antique shop, with hundreds of pictorial riddles from the pages of an almanac randomly pasted over its torso and leg, and with another doll's head disturbingly attached upside down on its groin. Razor blades are inserted into this second doll's head, with one sliced into an eye. The photographs immediately call to mind the violent re-articulations of Hans Bellmer and, more recently, the Chapman brothers. Through associations with Nadja, this object had been made as an embodiment of Luca's desire to form a rapport with André Breton, whom he admired and had met only once, briefly. As Luca expresses it:

The doll found in the shop window and the envelope full of riddles in the drawer only imposed their presence, violently, into my life at the moment when the desire to know B. [Breton] located in them the overt substitute means for doing this. The incubus found its full realisation through the use of these two magic objects in which I was also shortly to discern sorcery's demonic power. (pp.44-45)

There is something distinctly sulphurous in Luca's allusions, from his poetic hermeticism to the various thaumaturgical and satanic references that run through the book. Certainly, there was a ritual element to the creation of these objects, doubtlessly stemming from his participation in various collective games of the Romanian Surrealist Group; games of giving and receiving ‘awards' in absurdist ceremonial, and those of exploring the poetic qualities of objects in a darkened room through touch alone. These were games without competition, based upon exchange and complicity, without a predetermined point of arrival; through play the participants were able to explore the relationships that exist between subject and object, and the latent messages that are carried by the objects through a web of inter-subjectivity, in a ‘language of desire'.

Ghérasim Luca, The Ideal Phantom

A striking passage gives an account of an earthquake one night in the streets of Bucharest, a description that is both objective and oneiric, mediated by another OOO, entitled ‘The Ideal Phantom', which in Luca's interpretation brought together two subjects in the most extraordinary of experiences:

I was awoken at 4 a.m. by a dreadful earthquake: the walls were shaking, wardrobes flung across the room, books falling down on all sides, objects and glasses smashing. Throughout the duration of the quake I kept shouting that I knew it would happen. These powers of prediction, which I was discovering for the first time, only increased my terror. Half an hour later G. came over from the other side of town to see if I had survived, and told me the city was in ruins. I gave him The Ideal Phantom, and we went outside. The streets were full of destruction and rubble, and this town I'd never liked, with its stupid people, stupid streets, and stupid houses, was now unrecognisable, now it had a truly unique beauty, and scantily clad women traversed it like ghosts. (pp.56-59)

Luca expresses a desire to transform the world, even if this transformation was to be brought about by catastrophe, in an experience of convulsive beauty. A recombination of objects and subjects for Luca might even act as a precipitate of desire, provoking a genuinely revolutionary convulsion of reality that is inextricably bound up with social and political transformation and, one might say, without which revolutions that are simply concerned with a rearrangement of power relationships are doomed to failure. This very much holds true in our own turbulent times.

Following the poetic-scientific accounts of the OOOs, the second section of the book is entitled ‘The Passive Vampire'. This second section is more lyrical, its almost satanic litanies going beyond the psychoanalytic into more esoteric meditations upon the relationships between the self and the object, and eventually between existence and non-existence. Luca even contemplates objects as communicating between themselves, with the subject - like a phantom or passive vampire - attempting thereby to discern those mysterious, invisible connections that are present in the universe, but are revealed in rare moments when the conditions are right. Such objects have a magical power to effect change, whether consciously directed or as the instrument of unconscious forces. From the process of bringing together component objects into an assemblage, Luca is able to solve the magical cipher of desire, at which moment the object is then transformed into a vehicle for the desire invoked, capable of bringing that desire to reality through the revolutionary force of love. The object thus becomes a dark lantern illuminating internal and external realities, bringing together unconscious and conscious in a surreality. Luca's thinking might be dismissed as wild and wishful, but this is poetic thought at work in its most unrestrained form, striving to grasp the workings of objective chance, striving to discover a new language even:

a new language that genuinely expresses the psychic phenomena which resemble, but are not identical to, dream. This dream which, even if still opposed to external reality, has long since ceased to be opposed to the life of the dreamer. In this language, the one I have been unable to find, the ancient antinomies, beginning with that of good and evil, will be resolved for the meanwhile at an individual level. (pp.78-81)

The book closes with one final, extended account of an exchange of objects, in which an object made by Luca appears to deviate from its intended function as events unfold, to take control even, in a manner that has ill-fated consequences for its creator. The object, entitled ‘Déline-Fetish', constructed from a doll's leg, a 12-pointed star and a turbaned head on a metal stand, came to embody Luca's desire for a woman, Déline, with whom he had fallen deliriously in love. But rather than leading to the realisation of Luca's desire, the object somehow seems to bring about a baleful rupture between the couple. It is a poignant account of love that flares up violently and is abruptly lost, leaving us in darkness, on the cusp of Luca's despair.

Ghérasim Luca, Déline-Fetish

There is no doubt that The Passive Vampire should take its place amongst the essential ‘classics' of surrealism's history, but, moreover, it provides a valuable stimulus for any current investigations into the workings of chance and its objects, of dream and desire. As the translator, Krzysztof Fijalkowski writes in his excellent introduction, this work is important ‘as a fixed marker for the questions asked today by those wishing to situate themselves in the continuing stream of a critical surrealist thought.'

Kenneth Cox <surrealism AT madasafish.com>, a founder member of Leeds Surrealist Group, is editor of the magazine Phosphor and co-directs the Surrealist Editions imprint: http://leedssurrealistgroup.wordpress.com

Info

Ghérasim Luca, The Passive Vampire, translated and with an introduction by Krzysztof Fijalkowski. Prague: Twisted Spoon Press, 2008

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com