The Period of the Sleeping Fits

In his final Occultural Studies column, Eugene Thacker surveys the ‘unspeakable life’, work and dreams of surrealist poet, Robert Desnos

On the evening of the 25 September, 1922, a small group gathers in the apartment of André Breton on the Rue de Fontaine. They are mostly young, mostly writers, and, being young writers, mostly disenchanted with the world in which they live. They are ‘surrealists’, though on this evening the term doesn’t yet have the meaning that it would soon accrue through the endless manifestos, diatribes, scandals and group exhibits at art galleries. On this evening an experiment is being conducted within this group. One of them, René Crevel, has recently attended a séance, in which he witnessed the uncanny question and answer between a spiritual medium and spirits from the beyond. It occurs to him that such practices might be used as a writing technique. So, in the cramped apartment, with the street sounds outside and the quiet inside, they begin their sessions – seated in a circle, the lights turned down, the quiet of waiting. The first to be put into a trance is Crevel. Then Benjamin Péret. Both are asked a series of questions, and their slow, detached replies are carefully noted down.i

The next to go is Robert Desnos, who is a newcomer to the group, having only recently met Breton and his associates. Initially a sceptic, Desnos agrees to be hypnotised – indeed, he goes into a trance state so effortlessly he does it by himself. The experiment is repeated – seated in a circle, lights down low, waiting, and then the soft thud of Desnos’ head on the table. To questions like ‘Where are you?’ Desnos replies with ‘Robespierre’ – but instead of speaking he writes it down. Then more questions: ‘What is there behind Robespierre?’; and more answers, this time lethargically spoken: ‘A bird.’ ‘What kind of bird?’ ‘The bird of paradise.’ ‘And behind the crowd?’ ‘There!’ – Desnos draws a guillotine – ‘...the pretty blood of the doctrinaires.’ ‘And when Robespierre and the crowd are no longer in touch, what will happen then?’ ‘The beautiful love song of my life of my unspeakable life.’ii

Desnos quickly proved himself to be one of the most gifted in these experiments – eventually known as ‘the period of sleeping fits’. He was capable of writing, speaking, drawing and composing entire fantastical narratives. Eventually he could put himself into a trance state with great ease at any time, any place – it was no different than going sleep, and Desnos loved to sleep. He also excelled at word play. In one of the later sessions, on 7 October, Desnos was asked to improvise a series of texts while in trance. What resulted from the sessions were a series of short, lyrical bursts that indulge in alliteration and rhyme:

O mon crâne, étoile de nacre qui s’étoile

Oh my skull, mother of pearl which fades out

Au paradis des diamants les carats sont des amants...

In the paradise of diamonds carats are lovers...

Mots, êtes-vous des mythes et pareils aux myrtes des morts?

Words, are you myths and similar to the myrtles of the dead?iii

Desnos immediately set himself apart from the others. Whereas most of the surrealist séances produced a kind of delightful chaos, Desnos’ sessions produced texts that seemed to hover somewhere between sense and non-sense, the significant and the insignificant, the ordinary and the extraordinary, the prophetic and the mundane. As a reader, one wants to attribute to the texts some unspoken meaning that lies outside language; and yet, deep down, one also knows that the ‘meaning’ is beside the point. Many of Desnos’ texts in this style play around in this grey area between reading for meaning and reading simply as reading – as sound, rhythm, echo, and as silence.

Immediately following the séances, Desnos employed the new found technique to produce several books that are difficult to categorise, but which we could call ‘anti-novels’. One was published in 1924 as Deuil pour Deuil (Mourning for Mourning). It contains no characters but a mobile, roving ‘I’; no setting but instead a myriad of disparate spaces and places; no linear sequence of events but instead short sections of quasi-narrative that hover between prose and poetry:

As is fitting, I have taught old men to respect my black hair, and women to adore my limbs, but with respect to the latter I have always conserved my extensive yellow dominion where I ceaselessly confront the metallic vestiges of the high, inexplicable, pyramid-shaped construction in the distance.iv

But what will man have to say when confronted by these great mobilisations of the mineral and vegetable worlds, being himself the unstable plaything of the whirlwind’s farcical games and of the marriage between the lesser elements and the chasms which separate the resounding words?v

Respect my sleep, passers-by in the street below. The great organ of the sun makes you march in step, but I will not wake until this evening when the moon begins its prayer.

I will leave for the coast where ships never land; one shall present itself, a black flag fluttering at the stern. The rocks will part.vi

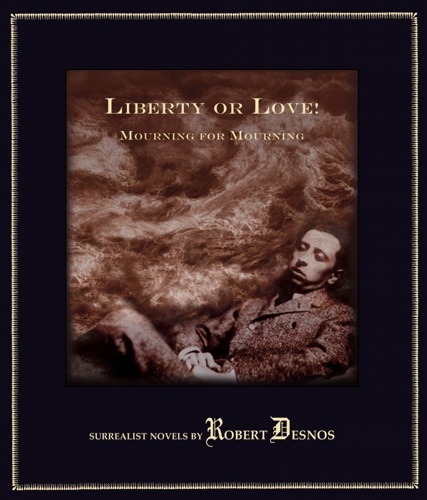

Image: Robert Desnos, Liberty or Love! and Mourning for Mourning, Terry Hale (trans.), London: Atlas Press, 2012

Of the surrealists who participated in the séances, Desnos was the only poet to make full use of the technique, and his poetry of this period shows its impact: the collections A la mystérieuse (1926) and Les Ténèbres (1927) contain what are arguably the most lyrical, most delirious, and most profound poetry that surrealism has produced:

I have so often dreamed of you, walked, spoken, slept with your phantom that perhaps I can be nothing any longer than a phantom among phantoms and a hundred times more shadow than the shadow which walks and will walk joyously over the sundial of your life.vii

Following Mourning for Mourning, Desnos began work on a longer prose text in the same vein, published in 1927 as La Liberté ou l’Amour! (Liberty or Love!). The book contains the same striking, lyrical phrases as Mourning for Mourning, but it also has more structure and a more constrained imagery:

Despite the darkness at these depths, the projected shadows of fish could be clearly seen as they flickered across the ocean floor. Corsair Sanglot prepared to go down. This was no easy matter since the reflection of his own image in the liquid element constantly got in the way of himself and his goal. But he closed his eyes, thrust his hands out violently before him, opened his eyes and grasped the hands of his reflection. The latter, as he retreated, reproduced on layer upon layer of water, rapidly dragged him to the bottom. He landed softly. Corsair Sanglot was buried up to his neck in a vast field of sponges. There must have been three or four thousand. Sea-horses, roused from their slumbers, rush out from all sides at the same time as a gigantic illuminated candle of some marine species. By the light of this candle, the rippling sponges stretched away as far as the eye could see. Their papillae stood out in extraordinarily clear relief, and it was only with difficulty that Corsair Sanglot forced a passage between them. Finally, he reached the candle. It rose up in a sort of clearing called, according to a legend inscribed in the coral: ‘The Glade of the Mystical Sponge’, where a herd of sea-horses was frolicking over a terrain composed of tiny black pebbles. The skeletons of a dozen mermaids were laid out side by side.viii

In Liberty or Love! we do get central characters – the fantastical protagonists Corsair Sanglot and Louise Lame – but they constantly undergo metamorphosis and jump from one place to another, in a kind of surrealist metempsychosis. Their names indicate their ambiguity – sanglot/larme (sob/tear), sang/lame (blood/blade) – an ambiguity also indicated in the title La Liberté ou l’amour!, echoing the revolutionary cry la liberté or la mort! (‘liberty or death!’), but also the more noirish ‘your money or your life!’ (similarly, the earlier work Deuil pour Deuil riffs on the saying ‘an eye for an eye’ – ‘mourning for mourning’ or ‘sorrow for sorrow’).

Liberty or Love! is a compendium of influences and a liquidation of them. There are hints of the 19th century prose poem – Charles Baudelaire, Arthur Rimbaud, Comte de Lautréamont – but this is counterbalanced by a touch of everything from Jules Verne to the Gospels to pop culture advertisements and references to marine biology. It is a book at once deeply lyrical and yet full of parody and the absurd. In spite of this eclecticism, Liberty or Love! contains a fairly consistent set of motifs, motifs that also run through Desnos’ poetry of the period: night, shadow, forest, the city, the erotic, and everything dealing with the sea, oceanic depths and marine life. With Desnos’ writing, there is a sense of everything emerging from and ultimately returning to the abyss of the sea.

Liberty or Love! also contains a number of unforgettable scenes, one of which is a convocation of the Sperm Drinkers’ Club, a heretical parody of the Eucharist as retold by the Marquis de Sade – if he were trained as a barista. We also visit a haunted boarding school for girls and witness a yacht party devoured by sharks. However, the bulk of Liberty or Love! uses techniques borrowed from Desnos’ sleeping fits to produce a narrative that constantly wanders and drifts - a kind of derelict, shipwreck narrative. In the chapter titled ‘Everything Visible is Made of Gold’, we see Corsair Sanglot walking at night with Louise Lame in the Tuileries palace. They then are in the hotel room of Jack the Ripper, preserved like a museum, where they examine all the objects in the room like relics. Erotic adventures ensue. And then suddenly Sanglot is in a small Spanish coal mining town, where a fight breaks out. Then he is back in Paris, but on the Rue de Rivoli, where café waiters are watched over by St. Raphael. Nearby, fish dedicated to ‘the cult of divine objects and celestial symbolism’ jump out of the water, as palm trees ‘desert their little alleys haunted by the peaceful elephants of childish sleep.’ Then Sanglot witnesses a funeral procession down the Champs-Élyssées hosted by Bébé Cadum (a grinning baby from a popular soap ad on Parisian billboards), who then begins a destroy-all-monsters bash with Bibendum Michelin (the Michelin Man, ubiquitous in the Michelin Guides). The battle suddenly shifts to the desert, where the blasphemous Paternoster of the False Messiah is composed, before the chapter closes with the prose poem ‘Golgotha’: ‘[...] The sky brightens violently with the glare of neon signs.’

If Liberty or Love! and Mourning for Mourning can be considered anti-novels, it is because they go against the grain of both traditional narrative forms as well as the early 20th century vogue for high modernism (à la James Joyce’s Ulysses). Desnos’ books contain no grand master plan, no baroque, structural puzzles, no erudite references or carefully calculated clues. Instead, Desnos offers writing that is half awake, half asleep, wandering and listless in free association, idleness, childhood reverie, and creative boredom. This is a poetics of sleepwalking, poetry as narcolepsy.

There is even a sense that Desnos goes against official surrealism, at least as it was cast in the hands of Breton. Against surrealism’s obsession with Freud, dream interpretation, and grand plans for revolution, Desnos offers something analogous to the luminous, ephemeral images of early cinema. The bodies, places, and objects in Desnos’ novels fade in and fade out, they dissolve into and apart from each other, they form jump-cuts and a melancholic montage of narcoleptic images. Indeed, in the late 1920s, as Desnos began to distance himself from Breton’s Surrealism, he began writing avidly about cinema.ix His essay, ‘Melancholy of Cinema’ (1927), asks, ‘where shall we spend out nights prey to dreams and hallucinations?’x

Mourning for Mourning

Desnos’ works have become available in reliable translations only recently. This past year Atlas Press, a London-based publisher specialising in the literary avant-garde, published a beautiful, hardcover edition of Desnos’ anti-novels Liberty or Love! and Mourning for Mourning.xi The cover of the book uses a frequently found image of Desnos asleep in a chair – not unlike the images that Breton would use in his 1928 novel Nadja. (In fact, I’m tempted to say that I’ve seen more images of Desnos asleep than awake – perhaps no other poet has been so frequently represented as sleeping...). The Atlas Press edition also provides an occasion to re-examine, almost a century later, surrealism as a poetic and literary movement – something that is often occluded in the emphasis on surrealism and visual art. Central to such a re-examination is the role that such ‘occult’ writing practices played in surrealism particularly, but also in the literary avant-gardes generally.

The participants of the séances were split on what exactly it all meant. For Breton, who was quickly becoming the mouthpiece for the fledgling surrealist movement, the ‘period of the sleeping fits’ were indicative of the untapped creative potential in the human mind. Appropriating the early 20th century vogue for spiritualism, séances, and the occult, Breton officially dubbed such techniques ‘psychic automatism.’ In the 1924 Surrealist Manifesto Breton attempted to wed spiritualism and Freud into a program for cultural liberation. He provided a definition of surrealism as

pure psychic automatism by which we propose to express, either verbally, or in writing, or in any other manner, the true functioning of thought.

For Breton the stakes were high – what was at issue was nothing less than a challenge to the status quo of cultural politics:

Surrealism is based on the belief in the superior reality of certain forms of association heretofore neglected, in the omnipotence of the dream, and in the disinterested play of thought.

For Breton it was but a small step from the sleeping fits to a more generalised cultural revolution, a revolution of thought ‘in the absence of all control exercised by reason, and outside all aesthetic or moral preoccupations.’xii

Desnos, for his part, was not so ambitious. While he had begun to write and publish his poetry, he seemed to be at once the paragon of surrealism’s psychic automatism as well as its patron saint of underachievers. Desnos was barely 20 when he first met Breton, along with Louis Aragon, Tristan Tzara and their circle at the bar Certà in Paris. As a teenager he was taken by the poetry of Rimbaud, the alchemical treatises of Nicolas Flamel and the popular noir series Fantômas. But he spent most of his youth wasting time. Desnos would later describe his own childhood:

At six I lived in a dream world. My imagination nourished with maritime catastrophes, I travelled on beautiful sailing ships towards enchanted countries. The parquet tiles were easily mistaken for tumultuous waves, in my mind the armchair was a continent and the upright chairs deserted islands.xiii

By contrast, a teacher once described him as ‘talkative, disorganised, disobedient, scatter-brained, negligent, unattentive, deceitful and lazy.’ He showed no promise scholastically and barely finished at a trade school, which enabled him to work as a translator of medical reports for pharmaceutical companies. His only friends were the likes of Benjamin Péret, Georges Limbour, and Roger Vitrac, all of whom were then participating in the Parisian Dada movement along with Breton and Tzara. While Dada was in full swing in Paris, Desnos did his military service and was subsequently stationed in Morocco until his return to Paris in 1922, where he began working odd jobs as a journalist.

For some years Desnos had been writing down his dreams. He had also begun, at the same time, writing poetry. It is not clear if at some point Desnos consciously decided he would become a writer; what is clear is that his gift for ‘sleeping fits’ seemed to open up a whole new linguistic universe for him that occupied his sleeping as much as his waking hours. Breton, not without a sense of envy, once described Desnos during this time:

I can still see Robert Desnos as he was in the days which those among us who have known them call the period of sleeping fits. Then he would sleep, but he would also write, he would also speak. It is on some evening in my studio above the Cabaret du Ciel. ‘Come on in, come and see the Chat Noir,’ someone is shouting outside. And Desnos goes on seeing what I do not see, what I see only as he gradually reveals it to me.xiv

Breton’s words are telling – they indicate a shared interest and yet, with Desnos, a certain opacity, as if one can never reach Desnos because, as Breton would put it, he is always asleep. In fact, one of the reasons why Desnos’ anti-novels are interesting is because they invite us to consider the difference between sleeping and dreaming. Desnos was the most gifted of the sleepers, but this is not the same thing as saying that Desnos was the most gifted dreamer. Perhaps, in our preoccupation with dreaming, we have forgotten how to sleep? It is interesting to note that, in his writings of this period, Breton almost never meditates at length on sleep. He is, however, quite verbose when it comes to dreams and dreaming. Breton’s idiosyncratic mix of Freud and the occult led him to revere, to idolise even, the dream and the dreaming state. The surrealist manifestos are replete with hymns to the evocative power of dreams, of their potential for both individual and collective transformation, of their use value for revolutionary disruption of cultural and social norms.

In short, Breton admires dreams so much because they contain potential depths of meaning and significance. But he virtually ignores sleep – other than as a byway to dreaming. By contrast, Desnos loves to sleep, not just because sleep is a passage to dreams, but, more importantly, Desnos loves sleep because sleep is the beautiful and mournful annulment of everything. The age old comparison of sleep with death is not lost on Desnos. Breton’s emphasis on the dream is a Freudian one, with an emphasis on hermeneutics, the meaning making activity of interpretation, on some secret to be uncovered, unlocked, and made into an instrument. For Desnos, sleep is less interpreting than it is an act, a doing – but a strange kind of doing that is also inactive, impassive, impersonal. For Breton, the dream holds everything, including the transformed self, the liberated collectivity, the promise of utopia. For Desnos, sleep is the paring down of all existents, the stripping away of all relations, a different kind of promise – the promise of oblivion. Breton, as the mouthpiece of surrealism, had promoted psychic automatism and in the process was able to bypass conscious thought, and to write without thinking. Desnos went a step further. He was able to write without even being awake.

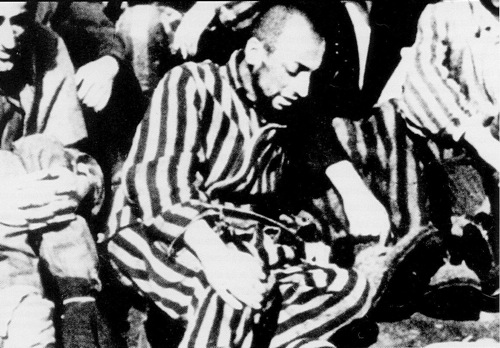

Image: Last known photo of Desnos in the Theresienstadt concentration camp, 1945

A Wave of Dreams

Eventually the sleeping fits had to come to an end. Things were getting out of hand (during one séance, Desnos reportedly grabbed a knife and chased Paul Éluard around the apartment). There was also a sense that the sleeping fits, and the strange, poetic oblivion they promised, were almost eclipsing the waking hours. In his 1924 essay ‘A Wave of Dreams’, Louis Aragon describes the almost threatening allure of the sleeping fits, in a passage that deserves to be quoted in full:

There were some seven or eight of us who now lived only for those moments of oblivion when, with the lights turned out, they spoke without consciousness, like men drowning in the open air. Every day they wanted to sleep more. [...] They went into trances everywhere. All that was necessary now was to follow the opening ritual. In a café, amid all the voices, the bright lights and the bustle, Robert Desnos need only close his eyes, and he talks, and among the beers, the saucers, the whole ocean collapses with its prophetic racket, its vapours decorated with long oriflammes. However little he is encouraged by those who interrogate him, prophecy, the tone of magic, of revelation, of the French Revolution, the tone of the fanatic and the apostle, immediately follow. Under other conditions, Desnos, were he to maintain this delirium, would become the leader of a religion, the founder of a city, the tribune of a people in revolt.xv

Exaggerated though it may be, Aragon’s description testifies to the tendency to get carried away when talking about Desnos’ writing. Even those who were otherwise critical of him – Breton most of all – cannot help but to admire, to envy even, the facility of Desnos’ narcoleptic poetry. There is a sense that Desnos’ texts rescind themselves in an act of linguistic self-annulment, proliferating images that seem to subsume themselves in the romantic imagery of oceanic oblivion, chimeral forests, and nocturnal city streets.

This rescinding characterised Desnos’ personal and poetic trajectory, through to his death in 1945. After the heady days of surrealism in the 1920s, Desnos spent most of the 1930s working in radio advertising, writing for cinema journals, and penning the occasional screenplay. After he was conscripted for service in 1939, he joined the resistance group Agir, wrote poetry under pseudonyms for publications such as Combat, and was in the process of putting together an underground journal when he was arrested by the Gestapo in 1944. Desnos spent the next year in a series of camps – Fresnes, Compiègne, Auschwitz, Buchenwald, Flossenbürg, Flöha, and finally to Theresienstadt. At Compiègne Desnos saw his lifelong companion Youki for the last time.xvi By the time he was en route to Theresienstadt, Germany was on the brink of collapse. Yet Desnos’ death came not in the camps, but just a few weeks after liberation. Malnourished and ill with typhoid fever, Desnos was relocated to an infirmary in Terezín (in the Northwest region of present day Czech Republic). There, Josef Stuna, a medical orderly, was going over the list of patients, when the name ‘Robert Desnos’ jumped out to him. As a student Stuna had read the surrealists, and recalled the image of Desnos in Breton’s Nadja. Stuna searched for Desnos among the 200 or so beds in the infirmary. He eventually found Desnos, bedridden and extremely weak. Stuna asked him, ‘Do you know the French poet Robert Desnos?’ No answer. And then, barely audible, ‘...that French poet, it’s me...’ Desnos slipped into a coma the next day. Three days after that, on the morning of 8 June, he died.

Desnos, the marine writer – the most pelagic of sleepers, the most demersal of poets. Desnos remains the most gifted of the ‘sleep writers,’ having perfected the technique to such a point that, one sensed, he could really write without thinking – and, in a way, is this not every writer’s dream?

Eugene Thacker <thackere AT newschool.edu> is the author of several books, including Horror of Philosophy (Zero Books) and After Life (University of Chicago Press). He teaches at The New School in New York

Info

Robert Desnos, Liberty or Love! and Mourning for Mourning, translated and introduced by Terry Hale, Atlas Press, 2012.

Footnotes

iAccounts of the initial séance sessions vary. Desnos’ own retelling is given in the collection Nouvelle Hébrides et autres textes, 1922-1930. Crevel, Aragon and both André and Simone Breton all give slightly different details which have become even more apocryphal with secondary accounts in the critical literature (e.g. by Mary Ann Caws, Catherine Conley, Anne Egger, Terry Hale, Pierre Berger, and others).

ii Adapted from The Automatic Muse: Surrealist Novels by Robert Desnos, Georges Limbour, Michel Leiris, Benjamin Péret, Terry Hale and Iain White (trans.), London: Atlas Press, 1994, pp.vi-vii. Excerpts from the séance sessions were later published in the surrealist journal Littérature.

iii The texts were published in 1922 in the journal Littérature under the title Rrose Sélavy (a play on eros, c’est la vie – also the pseudonym used by Marcel Duchamp). These translations adapted from Mary Ann Caws, The Surrealist Voice of Robert Desnos, Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1977, p.148.

iv Robert Desnos, Liberty or Love! and Mourning for Mourning, Terry Hale (trans.), London: Atlas Press, 2012, p.140.

v Ibid., p.141.

vi Ibid., p.160.

vii From the poem ‘J’ai tant rêvé de toi,’ in Essential Poems and Writings of Robert Desnos, Paul Auster (trans.), Mary Ann Caws (ed.), Boston: Black Widow, 2007, p.148. The original reads: ‘J’ai tant rêvé de toi, tant marché, parlé, couché avec ton fantôme qu’il ne me rest plus peut-être, et pourtant, qu’à être fantôme parmi les fantômes et plus ombre cent fois que l’ombre qui se promène et se promènera allégrement sur le cadran solaire de ta vie.’ (from Corps et biens, Éditions Gallimard, 1953).

viii Liberty or Love!, p.62.

ix Desnos is one of several writers considered ‘dissident surrealists’ due to their break from Breton’s increasingly authoritarian management of the movement in the 1930s. Desnos was one of those to sign his name to the 1930 pamphlet ‘Un Cadavre’ – an acerbic indictment of Breton and his statements in the Second Surrealist Manifesto of 1929. It is worth noting that Georges Bataille came under particular attack in the Manifesto, and many of the dissident surrealists would go on to collaborate with Bataille on, among other things, the journal Documents.

x In Essential Poems and Writings of Robert Desnos, p.91. A French edition of Desnos’ writings on cinema is Les Rayons et les Ombres: Cinéma, Marie-Claire Dumas (ed.), Paris: Gallimard, 1992.

xi Atlas has, over the years, made available little known, under read, literary gems from the late 19th and early 20th centuries, including Xavier Forneret’s The Diamond in the Grass, Alfred Jarry’s novels Days and Nights, Visits of Love, and Caesar Antichrist, Michel Leiris’ automatic novel Aurora, and Unica Zürn’s prose works Man of Jasmine and The House of Illnesses. Their covers for the 1990s editions of Desnos’ Liberty or Love! and for Breton and Soupault’s The Magnetic Fields are marvellous. Atlas also specialises in works of the Oulipo, Raymond Roussel, and the Vienna Group.

xii Andre Breton, Manifestoes of Surrealism, Richard Seaver and Helen R. Lane (trans.), Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1972, p.26.

xiii Cited in Terry Hale’s Introduction to the Atlas Press edition. Desnos’ text was titled ‘Confessions of a Child of the Century’ and published in 1926 in La Révolution Surréaliste.

xiv Andre Breton, Nadja, Richard Howard (trans.), New York: Grove Press, 1960, p.31, translation modified.

xv Also cited in Terry Hale’s Introduction. Originally published as ‘Une Vague de rêves’, Commerce no.2, 1924.

xvi On Desnos’ relationship to Youki (Lucie Badoud), see Mary Ann Caws’ Afterword to the Essential Poems and Writings of Robert Desnos. See also Youki’s own book Les Confidences de Youki and the collection of Desnos’ love poems Le Livre secret pour Youki.

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com