Nymphomaniac: Sex Against Gender

Lars von Trier’s Nymphomaniac considers the feasibility of love with men, and whether heterosexual fucking – or abjuring it – can be women’s self-propulsion into the making of history

This is what happens at the very end of Nymphomaniac: after the screen suddenly blacks out, our protagonist Joe shoots and kills her first and only friend, her confessor/therapist and clear stand-in for Lars von Trier. In what follows, I want to consider what the stakes of the interpersonal violence in this final scene might be. The protagonist who bears this empty, dudely name is primarily played by the witchy, more-than-human multitude that is Charlotte Gainsbourg. But, under her aegis, Joe is also Stacy Martin when aged between 15 and 30, Ananya Berg at age 10, Maja Arsovic at 7, and Ronja Rissman at 2. Five unified and interpenetrating Joes, whose collective actions have been weighed by the film’s embedded therapist-cinematographer, Seligman, and found to be forgiveable. By talking to him, Joe has been recovering, redeeming herself from bodily and spiritual near-death, but also undergoing humanisation in an ideological sense. Her interlocutor is a passer-by-cum-rescuer – a scholarly and nurturing Danish man – who at the film’s start but near the narrative’s end finds her beaten and broken in an alley and takes her into his own home. Tirelessly, this ‘Seligman’, a virgin, has argued against Joe’s claims that she is ‘a terrible human being’. Seligman’s compassionate intellect is what transforms into a Socratic dialogue the narration Nymphomaniac gives from her host’s bed. His interruptions and digressions are arguably what require his alter ego, von Trier himself, to extend the offering to two volumes. Yet, like other von Trier films, this one seriously considers the possibility of women abolishing the logic of gender and entering history, which is Joe’s motivation not only in her ‘whoring’, but in her formulating a vow of celibacy in the penultimate frame.

Even though only one in a million – as my dubious therapist says – succeeds in mentally, bodily, and in her heart, ridding herself of her sexuality, this is now my goal.

Joe’s retributive and righteous violence against Seligman comes at the end of an exhausting story-telling, lasting many days, that has prompted two in every three reviewers of Nymphomaniac to call Gainsbourg ‘a Scheherazade’ in order to then add one pathologising flourish or another (for instance: ‘of the genitals’). 1,001 Nights is not a totally expendable analogy, though. At the end of 1,001 Nights, as we know, the storyteller of legend was supposed to be executed just like the 1,000 twenty-four-hour brides who came before her. Instead, Scheherazade found that the king has fallen in love with her – an ending characterised as ‘happy’ on condition that one not turn over the former prisoner’s wedding ceremony, or its didactic meaning for women, too carefully in one’s mind. The stories Scheherazade told were, each of them, interesting enough to the man she told them to that they stayed, for a day, his prerogative to kill her. As long as she continued to make him love her in the morning, each tale could be a bulwark against the hatred men collectively – in their culture – feel for women. Each tale must therefore have contained a visceral knowledge of that hatred. How was that knowledge expressed by the condemned entertainer of the king? As love of men? Nymphomaniac recounts a campaign of desire against patriarchal society, but in the end, is there much that distinguishes the ‘Arabian’ sacrificial victim, masterfully creative in her desperation to survive, from the fantasy of von Trier, this simultaneously penitent and defiant woman as confessant to a forgiving and fatherly priest? In both cases, the woman’s speech is a magical spell that elicits a sigh of (in Seligman’s words) ‘little darling … I’m still not allowed to feel sorry for you?’ In both cases, a process of male redemption occupies the meta-frame, indulging her paradoxical but sincere impulse towards friendship, reached through courageous and protracted self-vulnerabilisation.

Interspersed with digressions of my own, and taking some liberties with the ordering, here are the tales offered to the king and viewer in Nymphomaniac I and II.

An infant and her friend pursue exploratory and onanistic bathroom flooding games. Hating the solitaire-playing of her ‘cowardly, stupid bitch of a mother’, she goes on nature walks with a father much enamoured of particular trees. On a hillside, a little older, the girl is transfigured into a nymphomaniac via a spontaneous and levitated pre-pubescent orgasm. In the accompanying vision, the two spirits who appear before her are identified by Seligman as Valeria Messalina, ‘the most notorious nymphomaniac in history’, and the Whore of Babylon, who rides on a ghostly bull.

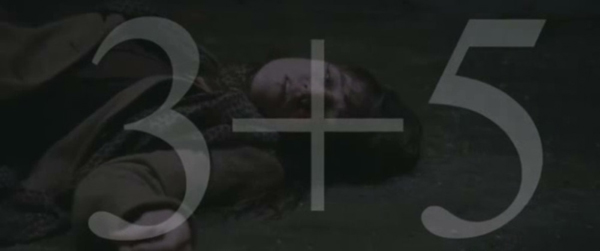

The girl, now older still, initiates her de-virgination by biker lad. Unlike her, he’s really bad at the mechanics of bikes and cars. And unlike the professional sadist we encounter later, this jerk’s species of malevolence is unidentified, and also unbounded, like a law of male nature. Three strokes are forced in a business-like way into her vagina, and then she’s flipped over for a further five in her arse. Seligman interjects that, actually, the unbearable way he fucks her fits into a sequence that is nature’s golden rule. Nymphomaniac is divided into 8 chapters of 5 + 3. Have you heard of Fibonacci numbers? Don’t worry, it’s all explained.

Following the trauma of ‘Jerôme’, the girl bounces back and forms a ‘nymph’ duo (with Sophie Kennedy Clark) dedicated to a scored game of anonymous serial train lavatory fucking, the rules of which she describes in detail. Seligman enthusiastically analogises every detail of the nymphomaniac’s method with the art of fly-fishing. Big fish hide in bends in the stream, it’s crucial to choose and bait the best fly (called a ‘nymph’), etcetera. It’s a ‘meta’ matter because fly-baited describes us, audiences buying tickets for a controversial ‘porno’ and coming face to face in bewilderment with a jocular treatise on despair.

The nymph who has been dangled in front of us is also the subject of a different metaphor used in the male validation of her ‘whoring’. Little bird, Seligman says encouragingly, ‘if you have wings, why not fly?’ Joe has a counter-cliché. ‘You can’t make an omelette without breaking a few eggs’. This can tickle you as variously as a pun on her sabotaging of maternal eggs, her breaking of testicles figuratively, or, in the language of Lacanian psychoanalysis, a reference to the ‘hommelette’ or ‘little man’ emerging into ego-hood out of traumatic fragments of imaginary egg.

With this as with the Fibonacci sequence reference, we’re invited to laugh knowingly at Joe’s expense. It’s hard to think of something more offensive than the mystification of these first ‘deflowering’ cock-thrusts as deep unwritten natural history, seeing as they already socially and psychologically mark the subjectivities in such an overdetermined way (those who’ve fucked us have somehow fucked us ‘for life’). On the other hand, if this mystification is itself made visible – not only that, but linked to multifarious forms of masculine domination over knowledge production and meaning-making – then the numerology in Nymphomaniac becomes, at least potentially, an evocation of naturalisation itself: of what it feels like to be coded ‘woman’. The distinctively hammy tone von Trier strikes, which flavours the whole, often going awry, blends ironising lightness with a tasteless existential hush; the ‘joke’ of men’s all being alike (which is always a joke at the expense of ‘woman’) and an unironic belief in the subjectivity of the Young Girl. At its best it’s a tone that puts itself at risk, like Donna Haraway in the Cyborg Manifesto when Haraway speaks of serious play – ‘my ironic faith, my blasphemy’ – and calls for concerted thought around ‘the partial, fluid, sometimes aspect of sex and sexual embodiment’.

But the abdication of mastery and control required by such an account of sexuated living is anathema to the foundational logic of a Bildungsroman. For all of Nymphomaniac’s lugubrious voiced-over narration, some things just don’t make sense, at least not in the way you want them to. For instance, at the sight of her father’s peaceful corpse, to her life-long shame, Joe’s cunt lubricates copiously where she stands. That Joe cannot make sense of this and other facts about herself is the life-long motor of her shame and perplexity, channelled into frustrated efforts to master her destiny and achieve positive knowledge.

The conditions of embodiment, as raced, classed and gendered, on capitalism’s earth are deeply conducive to depression, not to mention actively encouraging of helplessness: this currently is re-emerging as a topic of inquiry for anticapitalists in Britain. Nina Power, Arran James, Mark Fisher, the Institute for Precarious Consciousness and others are reviving the social materialist account of despair of clinical psychologist David Smail. The question of developing individual as well as collective counter-strategies against feminine distress is not avowedly political in Nymphomaniac. But in light of the rise of politicisations of anxiety, Lars von Trier’s trilogy on depression can open generative questions in the present. There is at least one hidden Easter egg of relevance to this in Nymphomaniac amid the heap of naïve glyphs that glitter in plain sight. We are told that ‘Seligman’ means ‘Happy Man’, but the name might also refer to Marty Seligman, a popular psychologist famous for his social critique of ‘learned helplessness’. In Nymphomaniac, Joe is the unhappy ‘man’ rebelling against her learned helplessness. Trying to cure herself of her raging sex-drive coercively, in the name of therapy, Joe lies suffering in her bed, avoiding the sight of all knobs and handles in her blacked-out home, eventually sucking on her fingers to give strangulated expression to her birthright, her Eros. By contrast, the uncontrollable seizures of Joe’s father, presented as madness and subjected (literally) to straitjacketing in the hospital where he dies, make a monstrous, leaking, hysterical spectacle full of Oedipal significance for Joe. At the heart of the von Trier universe, too easily mistaken for unsubtle heteronormativity, is this queer kernel, where Joe loves her daddy and identifies with him despite his messy effeminacy. These scenes suggest that mental ill-health is situated not only in mad, sad brides or bereaved mothers, as in Melancholia and Antichrist, but at the masculine subjective centre of society.

***

Stacy Martin’s eyes can be the saddest eyes in the world, and the years where she plays a young Joe simply ‘making hommelettes’ are like nothing so much as work. There are hollow pleasures: a montage captures the mischievous pretence, to dozens of men, that an orgasm bestowed by them was a ‘first’. What’s more, she falls in love after all. In fact, she is a secretary who falls in love with her boss, who is Jerôme, all these years later: the boy who hurt her holes in the sequence of 3 + 5. In both waged and unwaged spheres of her labour, Joe’s preference is for the lone white strike or war of attrition, so this is an era of extensive workplace copulation with everybody but Jerôme, a campaign of doomed defiance, inflected with her ressentiment over the politics – ‘effeminate’, ‘bourgeois’ – of a carelessly elegant man. She turns him down in an elevator.

Indeed, Joe has sworn never to sleep with the same man twice as part of her participation in a cod-satanic all-female cult (The Little Flock) that is dedicated to worshipping the destruction of love. As a mission, this forms a sensible response to childhood’s lessons. Joe’s error, in terms of her own interest, is to stand firm when the others in the Flock succumb to the insight that ‘the secret ingredient to sex is love’. Breaking her solidarity and storming out is her retaliation. Thus the defunct collective chant ‘mea vulva, mea maxima vulva’ comes to symbolise a self-isolating curse Joe has inflicted on herself, with a piano accompaniment of the tri-tone, or Devil’s interval.

I picture an alternate Scheherazade (squatting somewhere behind von Trier’s grossly objectionable public persona) contemplating how to package this wisdom carefully. If you don’t watch out, the boyfriend you never wanted will end up being your boss. And, after a haughty rejection and brief spell in the wilderness, you’ll end up a loving couple with him. Joe’s cry to Jerôme is always: ‘fill all my holes’, and he’s game. This brings a brief spell of giddy fun. For instance, in an extremely fancy café he offers Joe £5 if she can tuck a long sundae spoon inside her cunt. By the time they leave, one has to assume she’s earned close to £50 from her delighted boyfriend, and the waiter cannot comprehend why spoons are clattering noisily after he hands the departing Madame her coat. But the happenstance around the sun-dappled advent of love, in this tale, is so fantastical that a cut-away is required so that Scheherazade can advise: ‘Which way do you think you’d get the most out of my story? By believing in it, or by not believing in it?’

Jerôme soon tiresomely identifies his new partner as a ‘tiger’ and concedes that he can neither presently satisfy its tiring desire, nor fill its appetite for trying. For a brief moment, prior to being stricken numb – ‘I can’t feel anything, I can’t feel anything’ – Joe had actually smiled while having sex. What’s next, then, according to the logic of this curse, is the miserable tale of birthing Jerôme’s child, Marcel. The stainless steel equipment being used for the caesarean section clinks together, sounding, once more, the Devil’s interval. Mea maxima vulva: no child shall pass through Joe’s precious instrument. Marcel’s birth fills Joe with little more than disgust. Scenes of mass man-seduction follow, using a car’s expertly jumbled spark-caps as bait, with Joe in the role of the ingénue who knows nothing about cars. Soon enough, Joe is abandoning Marcel as well as Jerôme, and truly making a bee-line for social exile.

The most vertiginous horror in Nymphomaniac is the family. Why is this? Could it have something to do with Nymphomaniac barely passing the Bechdel test until its endgame?[1] By virtue of the possibilities omitted, rejected early, or come to too late – of living for women and sharing one’s life with them – the cosmic bleakness of Life According to Joe seems to have much to do with the gravitational pull of men. On the one hand, inorgasmic and loving cohabitation with a boyfriend is described by Joe as peaceful sanctuary. On the other, the things people do to each other inside ‘the family’ is arguably the ugliest part of the planetary social order for von Trier. It is, after all, a woman dedicating her life to the private sphere of the bedroom who believes that ‘for a human being, killing is the most natural thing in the world’. And the film, unlike Seligman the humanist, does a good job avoiding both pathologising and apologising for that opinion.

Indeed, Joe’s depression is one way of opening the question of why one would respect the human, want to be human, or reproduce humanity’s constitutive institutions. Far from being unwilling to love her child, Joe feels that the conditions of possibility for love are not present when she looks into Marcel’s eyes. She perceives (and, why not, accurately) that she is not loved back. Mutilated by this experience, her second attempt at parenting via informal adoption of a teenage girl, P, is contradictory. On the one hand, it’s an act of self-disgust, where Joe wallows in the mercenary, opportunist motive of converting a young girl into her useful and devoted bodyguard. While reproductive labour repelled Joe as ethically untenable when it came to the little boy, the corrupt and self-consciously harmful goal of self-reproduction as self-replication is her project in training the female P. On the other hand, P stands for a genuinely alternative bond formation, blending political guidance, erotic love, and un-parent-like frankness, raising a challenge of what parenting outside patriarchy could mean. ‘Don’t you see how evil [my plan to adopt you] was?’ Joe asks the girl. It prompts Seligman to say ‘Perhaps she really loved you. … You wanted it to be true’ – but, says Joe, voicing the movie’s cri de cœur, ‘if you find [the story] touching, you have misunderstood.’

Two other scenes approach a grotesque form of the sublime by merely expressing the banal truths of a heteromonogamous family’s foundations as self-mutilation. In Volume II, Jerôme excoriates Joe for having, alongside her love for Marcel, a co-existing desire to be beaten at night by her (other) sadist. Essentially he drives Joe out of the house by brandishing the child at her. He kisses her: ‘if you leave tonight, you’ll never see me or Marcel ever again.’ His words are a very refined torture composed of nothing other than sentiments of reasonableness drawn from norms around privatised, nuclear parenthood, and people’s gendered ‘fitness’ for it, norms we usually can’t even make visible anymore as they’re so totalising (Lee Edelman identifies ‘reproductive futurism’ as the foundation of all present-day politics). Jerôme performs a kind of boyfriend archetype, i.e. pure blackmail: ‘Marcel! Aw, baby boy! … Look at him, Joe! See! He wants you … Let’s face it, Joe, you’re not a mother.’

What is a mother? What are mothers produced to be like? The viewer remembers it well. In Volume I, Mrs H brings all three of her small sons into Joe’s apartment to see ‘the whoring bed’, ‘Daddy’s favourite place’. This is Uma Thurman’s tour de force, an almost magic-realist imagining of the bright, manic, quasi-ecstatic pain of the wife penetrating into where her husband is – the Other Woman’s abode. In prelude to the occasion, Joe had falsely claimed to love (‘too much’) a spineless adulterer, Mr H, who wouldn’t take leave of her flat post coitus. It backfires on a gigantic scale because, instead of disappearing from Joe’s life, he returns, lugging suitcases, ready to join it. On the stairwell, tragicomically, the family lurks. ‘I hope it’s all right that the children call their father “Daddy” here,’ Mrs H asks Joe with exquisite poise. ‘If you prefer, they can call him “Him” or simply “The Man”?’

Thurman even goes so far as to make tea for everyone in Joe’s kitchen, instructing Joe on how many lumps of sugar Mr H likes to take. She apologises for intruding – an intrusion all the more excruciating for being characterised by Joe’s and Mr H’s near total silence – ‘I thought it only right’, she explains, ‘that their father be confronted by the little people whose lives he’s destroyed.’ As Joe will later know, ‘to destroy a mesh of feelings woven over twenty years is no joke.’ At last, taking her leave of this ‘joke, too cruel’, having heard Joe say, ‘boys, I don’t love your father’, Mrs H screams like an animal on the stairwell. But as she bounced, smiling a little madly, on the nymphomaniac’s mattress together with her three sons (significantly, like Marcel, they are sons) Mrs H embodies perfectly the Larkinian principle: they fuck you up, your mum and dad, they may not mean to, but they do. ‘You should try to memorise this room,’ she coos to them, ‘it will stand you in good stead later in therapy.’

It’s a good joke, this reference to the biopolitical ‘therapy’ that is so evidently, with its soft-patriarchal codes, part of the problem (for women); begging the question of what a praxis of collective anti-psychiatry might look like. To further consider the potentially radical critique of hetero-familiality that can be elicited from Nymphomaniac, one should bring into focus Joe’s progressive isolation from other women. During childhood, Joe’s bathroom masturbation came up against her mother’s repressive distaste (only her father permitted it). Beyond that, there are five crucial moments that chart the learned transmutation of Joe’s dissatisfaction into a quasi-fascist disgust for other women: her direct but still comradely sexual competition with B on the train; the para-political ‘maxima vulva’ co9 – Joe had actually smitic implosion; the indirect and, for Joe, uninvested sexual competition with Mrs H I’ve just delineated; Joe’s full-blown attack on an all-female Sex Addicts Support Group that has welcomed her; and finally, P’s righteous attack on Joe (on which, more later). The two failures of collective endeavour are mirror images of each other: desertion of the Little Flock is ultimately motivated by the purism of Joe’s loyalty and the idealism that drives her to ‘expect more’ from her sisters. Likewise, desertion of the sex-addiction group therapy (which won’t let her say the word ‘nymphomaniac’) is insurrectionary on its face: ‘You’re nothing but society’s morality police, whose duty it is to erase my obscenity from the earth so that the bourgeoisie won’t feel sick’. It is certainly informed by fragmented fidelity to the punk spirit of her just-pubescent self, a mirage of whom sits demurely on the periphery of the circle of chairs. But it principally bespeaks internalised and misogynous individualism – ‘I’m not like you … YOU just want to be filled up!’ – the origins of which are in the experience of failed collective feminist action, a disappointment in herself hatefully projected onto supposedly weaker women. The falseness, causelessness, of her rebellion is matched (though I’m not sure how consciously) by the cheap thrill of the visual line von Trier draws under this episode, juxtaposing a burning car with Talking Heads’ ‘Burning Down the House’. The desire to riot is present, but of course, a real riot requires many.

Notwithstanding its cringe-worthy tendency to talk down, Nymphomaniac can be read as a convincing critique of attempts to wage battle on reproduction using an individualist and gender-normative paradigm, in which the goal is, unfulfillably, something like overcoming the patriarchy one cock at a time. The noir of Mrs H’s joke about therapy also speaks to the dubious therapist relation Joe enters into with Seligman and casts big doubts on any ‘talking cure’ for the wounds of gendered reproduction. Rather than submit to her own slow subjective death, Joe does, in fact, act out to help herself, namely, by ceasing the relationship with Marcel and Jerôme. Admittedly, walking out is a kamikaze action in the face of a non-choice proffered by Jerôme’s blackmail. The conjuncture offered no avenues for self-love. Severed from any supportive bonds with other women, Joe accepts (or has to accept) the logic linking reproductive life with the total deprivation of one’s extra-economic libidinal energy, in her case, ‘filthy dirty lust’.

But while Joe, the creature of a very lonely battle, can only experience the family as tragic, Nymphomaniac defamiliarises the family form by making legible the constraints on Joe’s ability to contest the definition of motherhood. The film demonstrates not only the gentle, structural sadism of the boyfriends we love, but the insufficiency of even those paltry available alternatives to maternal solitude (for instance, the unreliability of babysitters). It denaturalises the familial entrapment of humans’ desire in the normal, nuclear, typically hetero-monogamous domestic sphere, which always appears in von Trier’s hands as a profound violence against both adults and ‘their’ children.

In Antichrist, one half of the antichrist dyad is Charlotte Gainsbourg’s husband and doctor, who takes it upon himself (not unlike Seligman) to subdue her pain and sense of responsibility over one mutual, unwitting crime. An unforgettable scene: the couple’s infant boy falls from a balcony while their backs are turned. The very love-making that made him in the first place later became the unmaking of the child. Far from gratuitous with its violence, Antichrist introduces von Trier’s take on the tragic antagonism between desire and reproduction, or Eros and familiality. It is not a ‘natural’ antagonism, but one rendered tragic by social and historical forces like the ideology of nature itself.

The balcony scene is quoted whole in Nymphomaniac. The difference is, in Nymphomaniac, the child is knowingly and consciously abandoned by his mother. Rather than reinscribe the blame for this, which Joe already accepts, the film, like several of von Trier’s other films, deeply calls into question the fate of children in a world dominated by the couple form. What it is to be a child in this social context, where collective structures are not in place to insure against the ravages of desire, Joe evokes in a memory from her childhood. Alone, immediately prior to an operation but already under anaesthesia, she felt a kind of loneliness so vast that it filled the entire cosmos with her tears. Her melancholia is pictured as a direct quotation of Melancholia, in awe-inspiring galactic pink and blue, to the sound of César Franck’s violin sonata.

In the endgame, Joe transitions, via an interview with her Antichrist counterpart, the wicked Willem Dafoe, into a kind of repo dominatrix extracting cash by deploying the dark arts of her intimate fieldwork on men. It’s a depraved career, a logical extension of the pathos of Joe’s apolitical anger, in which she tortures the wealthy – for instance, unearthing repressed paedophile desires. It’s the weakest part of the second volume; a somewhat contrived way of fast-forwarding to a point where the familial can resurface in incestuous form.

This final chapter of Nymphomaniac treats Joe’s erotically charged pseudo-parenthood of P. Lying in bed, ‘Lemon Incest’ style, the two reprise the relation between the girl Joe used to be and her pre-delirium father, in whose memory she’s kept a leaf-book or secular witch’s herbarium. Their stolen Sapphic season, their tender alternate reality, brings tears to Joe’s eyes, but is not allowed to last; soon enough, the law of the boyfriend reasserts itself with a vengeance. Thus, one day, P, the protégée-cum-trainee-cum-lover of the underground mafia queenpin Joe has become, falls in love behind Joe’s back. The man in question – recalling the earlier rule, ‘how do you think you’ll get more out of this story…?’ – is none other than the long-estranged Jerôme (now a haggard Michael Pas). For every hundred people killed for love, Joe said, there will be only one killed for sex. What induces her to pull the trigger of the gun she confiscated from P has as such been flagged. It is love: the force that killed her orgasm, requiring her to walk through the valley of death in order to regain it amid a torrent of lacerating blows.

Love, Joe ever averred, amounts to a putrid mingling of lust and jealousy. So, Joe shoots at Jerôme but has not racked the gun. This despite her enthusiasm for Bond movies and full knowledge of the greatness of the Walther PPK – as the film emphasises with a mini-montage (Nymphomaniac’s typical and somewhat infuriating mansplaining device) of gun-rackings. One might well ponder here, refining the Bechdel test further, how often we ever see women rack guns. Rihanna in ‘Man Down’, Karen Lancaume in Baise-Moi, don’t actually rack them. At any rate, Joe can’t fire, and stands still, whereupon Jerôme knocks her down. Having kicked her half to death for the mawkish denouement, he turns and fucks the girl, who maintains eye contact with her foster-mama as she drops her pants in the alleyway: receiving three thrusts to her cunt and five in her arse; Fibonacci as destiny. As a completing gesture, P then stands and sadistically urinates. A piss-soaked Joe has attained a holy, ecstatic state of abjection – laid out on the cobble-stones, her posture recalls the levitated nap on the hillside of her childhood. We’ve jumped the shark with Joe, back out of the confusion of contingent and anomic sex-war banality and into the portentous sphere of the lives of saints. ‘Fill all my holes,’ she murmurs aloud, once more, after her righteous tormenters have disappeared. When Seligman scrapes her up, she does not let him wash the piss off her jacket, nor wash away, by implication, the sense of the non-trivial, the ‘event’, she has inhabited.

‘A Scheherazade of the genitals’? The critics imply by this that the original Persian prisoner had no such thematic limitation.

***

The king will forgive and marry you, or kill you now, as all is said and done. Had you forgotten that? Or did you get more out of the story by believing so deeply in its own consequentialist logic that you believed it would necessarily transcend that script, break free of the numerology of those relations, and set you free? Joe, though no prisoner, believed so, and wants to act to confirm it as true. She believes in Seligman as an ally, and you should never trust someone who constantly tells you that, being human, you’ve done no harm. Rather, her oscillation between pride and shame about the harm she’s done need not be rationalised. To place a vow of celibacy on the moment through bruised lips – ‘I will muster all of my stubbornness, my strength, my masculine aggression…’ – is to work with the kind of linear myth-making about heroic redemption we get in hagiography (and classic therapy!). It is to subordinate the harmed to the triumph of one’s individual learning curve. As such, Joe falls right back into the trap of demanding access to male history, instead of embracing the unknown of an alternate temporality.

It’s a trap. Ritually abjuring one’s sexuality goes together, historically, with worshipping gods (Vestal virgins); or fetishising Christ (medieval anchoresses); or reigning over an Empire (Elizabeth I); or maybe preparing a husband for the crown (Lady Macbeth). Still, it’s the only way Joe feels she can henceforward live her life. ‘I will stand up against all odds, just like a deformed tree on a hill.’ It being time to sleep, Seligman says ‘I’ll make sure you’re not disturbed’. He seems about to run away with the film’s ‘feminist’ last word:

‘You were a human being … more than that: you were a woman, demanding her right. … [What] if a man had led the life you had? … When a man leaves his children because of desire, we accept it with a shrug. But you, as a woman, you had to take on a burden of guilt that could never be alleviated. All in all, all the blame and guilt that piled up over the years became too much for you, and you reacted aggressively. Almost like a man, I have to say!’

‘But I wanted to kill a human being.’

‘But you didn’t. … I call it subconscious resistance. … Deep down, you celebrated human worth.’

Joe is so relieved at her soul not being that of a murderer, she’s compelled to cement her future as an unsexed subject that ‘celebrates human worth’. For Seligman the all-forgiving, hearing the forming of Joe’s resolution ought to be somewhat humbling, but it is Joe who is humbled. ‘I want to say thanks,’ Joe continues, with a script almost as though von Trier imagines Gainsbourg already thanking him at the awards ceremonies, ‘thank you to my new and maybe first friend.’ Lights out. Joe is soundly sleeping. And the Happy Man is back: creeping cock in hand, he has come not to ask for sex, but to take it. She awakens to find him manoeuvring against her body and gasps: ‘no’. With this, he seals his fate by forming the protestation ‘But you’ve slept with thousands of men!’

The transgression of solidarity he commits is all the more breathtaking for the fact that it could only come as a surprise to true believers of the congenial, atheist humanism he has expounded for four hours to Joe, i.e. what she smilingly rejected at first as ‘the clichés of our times’. Revealed to us very much the hard way, here, in our gun-sights, stands the teacher and beneficiary of the moral law, always a self-exemptionalist. Why emulate that feel-good notion of the human, the lie that the final visible frame in a cinema usually tries to tell us? Rather than leave us with a friendship between Joe and Seligman, turning her into a ‘happy man’, Nymphomaniac, for all its weaknesses, ends well. This is your new best friend, it says; he must get a bullet in the head. With the lights off, after you’ve stopped addressing yourself to him, you just might find the end of the end of history out there, beyond the end of the written story. Look at him: he is blessing your integration into male supremacist culture. He won’t let you hate yourself. He will only reason as to why he can rape you. Basically, the thing about men is that they force you to kill them. That’s arguably the main way in which they ruin you. Yet, there’s always the question the darkness poses, of where you run and what you do next.

Sophie Lewis is a writer, student, and Plan C member living in Manchester, UK. On Twitter she is @lasophielle.

[1] The Bechdel test requires films to involve (a) more than one woman (b) talking to one another (c) about something other than men.

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com